Kabul, Afghanistan — For many girls in Afghanistan, the once-expansive horizon of education has narrowed to a stark choice: religious instruction or nothing at all. This reality, driven by the Taliban government’s sweeping prohibition on secondary and higher education for females, is reshaping the lives of millions and raising profound questions about the nation’s future.

At just 13 years old, Nahideh already understands the harsh limits imposed on her aspirations. Her days include working in a cemetery, collecting water to sell to mourners, a stark contrast to her dream of becoming a doctor. As her primary schooling, the current legal limit for girls, concludes, she faces the inevitable: enrollment in a madrasa, a religious school, to learn “about the Quran and Islam — and little else.”

“I prefer to go to school, but I can’t, so I will go to a madrassa,” Nahideh articulated, her dark brown eyes visible beneath a tightly wrapped black headscarf. She added with resigned clarity, “If I could go to school, then I could learn and become a doctor. But I can’t.”

Afghanistan stands as the sole nation globally that prohibits girls and women from pursuing general education at secondary and higher levels. This ban represents a significant component of a broader crackdown on women’s rights implemented by the Taliban since their resurgence to power in August 2021.

The Taliban government has imposed stringent regulations governing women’s attire, their movement, and even their companions, mandating the presence of a male guardian for travel. In July, the International Criminal Court sought arrest warrants for two prominent Taliban leaders, citing the persecution of women and girls as evidence of crimes against humanity.

Responding to these accusations, the Taliban denounced the court, asserting that it demonstrated “enmity and hatred for the pure religion of Islam.” While some Taliban leaders initially suggested that the suspension of female education would be temporary, with mainstream schools reopening once security issues were resolved, four years have passed, and the fundamentalist faction seems to have the upper hand.

Non-religious schools, universities, and even healthcare training centers remain inaccessible to half of the population. According to a report released in March by UNESCO, a United Nations agency, nearly 1.5 million girls have been barred from attending secondary school since 2021.

Explaining the closure of these institutions on state television in December 2022, the acting Minister of Higher Education, Nida Mohammad Nadim, stated, “We instructed girls to wear proper hijabs, but they did not comply. They wore dresses as if they were going to a wedding ceremony.” He further added, “Girls were studying agriculture and engineering, but these fields do not align with Afghan culture. Girls should learn, but not in areas that contradict Islam and Afghan honor.”

In stark contrast to the closures, the number of madrasas educating both girls and boys across Afghanistan has surged. Data from the Ministry of Education indicates that 22,972 state-funded madrasas have been established over the past three years, reflecting a significant expansion.

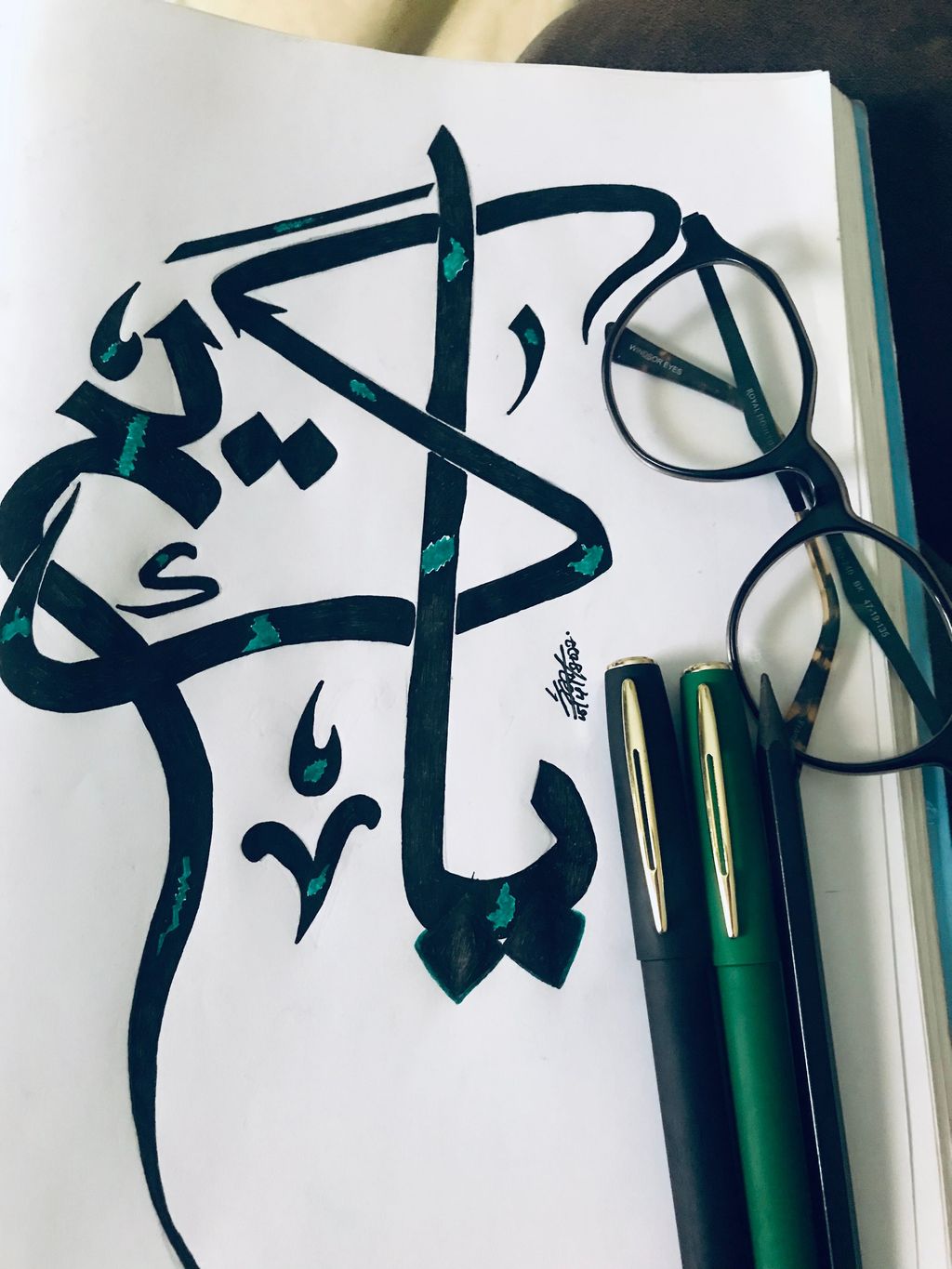

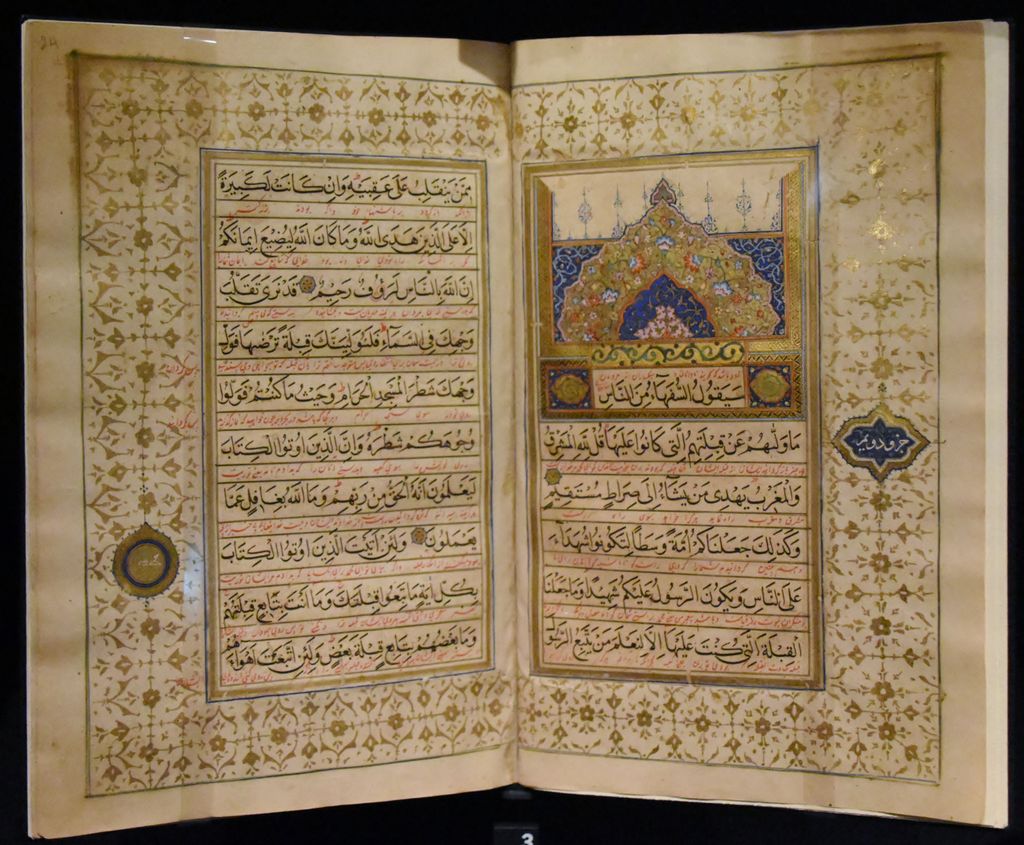

Enrollment at institutions like the Naji-e-Bashra madrasa, a girls-only religious school on the outskirts of Kabul, has skyrocketed since the Taliban began restricting girls from “mainstream” education. Inside, the echoes of dozens of girls reciting Quranic verses fill the hallways, with golden-lettered Qurans and religious texts piled on classroom floors.

The curriculum at all madrasas nationwide is dictated by the Taliban. While private facilities, often funded by students’ parents, might offer slightly more flexibility to include languages and science alongside Islamic studies, public madrasas, directly funded by the Taliban government, maintain a curriculum that is “almost entirely religious in content.

A report published last December by the Afghanistan Human Rights Center, a human rights monitoring group, alleged that the Taliban’s 2022 school curriculum plans “not only fail to meet the human development goals set by international human rights instruments, but also teach students content that promotes violence, opposes the culture of tolerance, peace, reconciliation, and human rights values.” The report further asserted that the Taliban has “tailored educational goals to align with its extremist and violent ideology,” amending history, geography, and religious textbooks and prohibiting the teaching of concepts such as democracy, women’s rights, and human rights.

Shafiullah Dilawar, the principal of the Naji-e-Bashra madrasa and a self-declared long-time supporter of the Taliban, expressed satisfaction with the current educational framework. “The students are very content with our environment, our curriculum, and our approach,” he affirmed, suggesting that the madrasa’s curriculum is “highly beneficial for preparing mothers for their roles in society, enabling them to raise well-behaved children.”

Dilawar dismissed any claims that these institutions serve to advance the Taliban’s ideological agenda. He maintained that, given the deeply religious nature of the Afghan population, many families find this form of education for girls satisfactory and urged the international community to support his efforts. Despite repeated requests, the Taliban leadership declined to grant an interview.

Many Afghan women, however, view madrasas as an inadequate substitute for the comprehensive education they increasingly accessed during the two decades preceding the United States‘ withdrawal in 2021. Nargis, a 23-year-old woman in Kabul who spoke under a pseudonym for her safety, exemplifies this sentiment.

“I have never had any interest in attending a madrasa. They do not teach us what we need to learn,” Nargis stated, reflecting on her past life as a diligent student of economics at a private university. She recalled attending morning classes, working a part-time job in the afternoons, and teaching herself English in the evenings, never tiring of learning.

“If four years ago you had asked me what I wanted to do with my life, I would have had lots of goals, dreams, and hopes,” she recounted wistfully. “At that time, I wanted to become a very successful businesswoman. I wanted to import goods from other countries. I wanted to establish a big school for girls. I wanted to attend Oxford University. Maybe I would have owned my own coffee shop.”

All of Nargis’s aspirations were irrevocably altered in August 2021. She was barred from classes, lost her employment, and felt her future dreams dissipate, simply because she was a woman. The profound despair intensified when her younger sisters, then 11 and 12, came home one day to announce that their school had been closed.

“They didn’t eat anything for a month. They were distraught,” Nargis recalled, her voice heavy with emotion. Confronted by their distress, she resolved to act: “I realized they would go crazy like this. So, I made the decision to help them with their studies. Even if I lose everything, I will accomplish this one thing.”

Nargis began gathering her old textbooks and instructing her sisters. Soon, other relatives and neighbors requested her assistance, a plea she found impossible to refuse. Every morning at 6 a.m. sharp, before the Taliban security guards are awake, approximately 45 female students, some as young as 12, discreetly make their way across the city to Nargis’s family home.

Operating without external support or funding, the girls often share a single textbook, along with notepads and pens, as Nargis imparts her accumulated knowledge of mathematics, science, computing, and English. The constant fear for her students’ safety looms large. “It’s extremely dangerous. There isn’t a single day in the week when I can relax. Every day when they come to me, I worry so much. It makes me furious. It’s a significant risk,” she confessed, dreading the discovery and shutdown of her makeshift classroom.

Two months prior, the home she used for teaching was raided by Taliban members, resulting in her spending a night in jail and receiving a reprimand for her work. Her father and other male family members implored her to cease her activities, arguing that the risk was too great. Yet, despite her terror, Nargis steadfastly refuses to abandon her students, switching locations and continuing her vital work.

Her personal ambitions have also suffered significant setbacks. Nargis had been enrolled in a US-funded online Bachelor of Business Administration program. However, that program was canceled last month, a consequence of the Trump administration’s decision to terminate 1.7billionworthofaidcontracts,ofwhich500 million remained undisbursed.

This cancellation was, for Nargis, “the nail in the coffin” for her aspirations, marking “the cancellation of my hopes and dreams.” Despite her efforts to remain productive, a pervasive sense of despair often encroaches, leading her to question the purpose of such immense effort and risk for an education that may lead nowhere.

In Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, women are prohibited from interacting with unrelated men and are barred from pursuing professions such as those of doctors, lawyers, or most public sector roles. “My mum was never educated. She always told us how it was under the previous Taliban government, and so we studied hard… But what is the difference between me and my mum now?” Nargis questioned, reflecting on the grim symmetry.

“I have an education, but we are both at home. For what purpose are we trying so hard? For what job and what future?” she articulated, capturing the profound disillusionment faced by a generation of educated women now confined to their homes.

At the Tasnim Nasrat Islamic Sciences Educational Center in Kabul, Zahid-ur-Rehman Sahibi, the director, notes the increased interest in religious schools. “Since the schools are closed to girls, they see this as an opportunity,” he remarked. “So, they come here to stay engaged in learning and studying religious sciences.”

This center accommodates approximately 400 students, ranging in age from three to 60 years old, with 90 percent being female. Their curriculum focuses on the Quran, Islamic jurisprudence, the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad, and Arabic, the language of the Quran. Sahibi observed that most Afghans are inherently religious, noting, “Even before the schools were closed, many used to attend madrassas,” but interest has “increased significantly, because the doors of the madrassas remain open to them.”

Official figures on current madrasa enrollment for girls are unavailable, but the overall popularity of religious schools is evident. Last September, Deputy Minister of Education Karamatullah Akhundzada reported that over one million students had enrolled in madrasas in the preceding year alone, bringing the total enrollment to more than three million.

Faiza, a 25-year-old woman who enrolled at the Tasnim Nasrat center five months ago, reflects a common sentiment among students. Kneeling at a small plastic table in a basement room, with her pencil tracing Arabic script, she explained, “It is very beneficial for girls and women to study at a madrassa, because … the Quran is the word of Allah, and we are Muslims.” She added, “Therefore, it is our duty to know what is contained in the book that Allah has revealed to us, to understand its interpretation and translation.”

Faiza’s original ambition was to study medicine, a pursuit she acknowledges is now impossible. Nevertheless, she holds onto the hope that her dedication to religious studies and a pious life might eventually allow her to pursue medical training, one of the few professions still open to women in Afghanistan.

Sahibi, her teacher, expressed a broader perspective on education for women. “In my opinion, it is very important for a sister or a woman to learn both religious sciences and other subjects, because modern knowledge is also an essential part of society,” he stated. “Islam also recommends that modern sciences should be learned because they are necessary, and religious sciences are important alongside them. Both should be learned concurrently.”

The ban on female secondary and higher education has not been universally accepted, even within the Taliban’s own ranks. In a rare public display of dissent, Deputy Foreign Minister Sher Abbas Stanikzai publicly asserted in January that there was “no justification for denying education to girls and women.

Read more about: Beyond Gender: The Rise of Unisex Baby Names and Why Parents Love Them

His remarks were reportedly met with disapproval from the Taliban leadership; Stanikzai is now officially on leave and is widely believed to have left the country. However, his statement underscored the recognition among many in Afghanistan of the profound, long-term ramifications of denying education to girls.

Catherine Russell, UNICEF Executive Director, issued a stark warning in March at the commencement of Afghanistan’s new school year. “If this ban persists until 2030, over four million girls will have been deprived of their right to education beyond primary school,” she stated. “The consequences for these girls — and for Afghanistan — are catastrophic. The ban exerts a negative impact on the health system, the economy, and the future of the nation.”

For some in this deeply conservative society, the significance of Islamic teachings cannot be overemphasized. Mullah Mohammed Jan Mukhtar, aged 35, who oversees a boys’ madrasa north of Kabul, holds this conviction. “Learning the Holy Quran is the foundation of all other sciences, whether it is medicine, engineering, or other fields of knowledge,” he explained. “If someone first learns the Quran, they will then be better equipped to learn these other sciences.”

Mukhtar’s madrasa, which opened five years ago with 35 students, now accommodates 160 boys aged five to 21, with half of them residing as boarders. Beyond religious studies, the institution provides a limited range of secular subjects, including English and mathematics. He also noted the existence of an affiliated girls’ madrasa, which currently has 90 students enrolled.

“In my opinion, there should be more madrassas for women,” asserted Mukhtar, who has been a mullah for 14 years. He emphasized the critical significance of religious education for women, stating, “When they are aware of religious rulings, they gain a better understanding of the rights of their husbands, in-laws, and other family members.”

As the sun sets over Kabul, casting long shadows across homes and madrasas, the educational landscape for Afghan girls remains one of profound paradox. While thousands are now channeled into religious institutions, some of which offer limited opportunities for broader knowledge, the desire for a diverse education persists among many, prompting brave, clandestine efforts in the face of overwhelming odds. The future of a generation, and indeed of the nation, hinges on this deeply contested right to learn, a struggle that continues to unfold through quiet acts of defiance and public declarations of despair.

The echoes of Quranic verses now blend with the silent aspirations of girls who once aspired to become doctors, engineers, and business leaders, a testament to a society struggling with its own identity and the fundamental right to knowledge. This ongoing expansion of religious education, coupled with the conspicuous absence of general schooling, marks a pivotal moment for Afghanistan, shaping the destinies of its young women and the very fabric of its society for the years ahead.