In the vast expanse of the Pacific, where tiny specks of land often held disproportionate strategic importance, lay Wake Island—a remote coral atoll that, in December 1941, became an improbable crucible of American defiance. This small outpost, barely a blip on the map, was about to be plunged into one of the most intense and poignant battles of the early Pacific War, showcasing an extraordinary resilience against overwhelming odds. It was a narrative of courage, desperation, and unexpected victories that would briefly electrify a nation reeling from disaster.

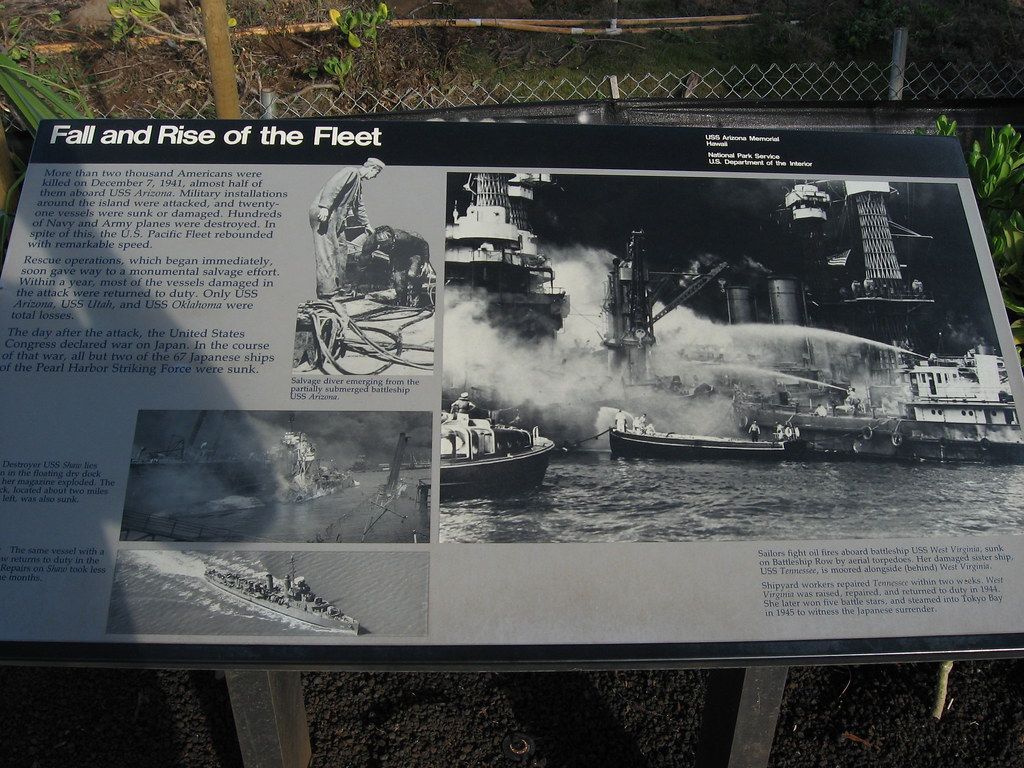

The unfolding drama at Wake Island, occurring almost simultaneously with the attack on Pearl Harbor, would quickly capture the American imagination. Against a numerically superior and highly experienced Japanese force, a small contingent of U.S. Marines and their ground crews, armed with aging artillery and a handful of fighter planes, would etch their names into history. Their defense became a symbol of stubborn resolve in a dark hour, revealing the fierce fighting spirit that would define the war in the Pacific.

This is the compelling story of how a handful of F4F-3 Wildcats and a few hundred Marines stood their ground against the might of the Imperial Japanese Navy, a testament to what can be achieved when hope seems all but lost. We’ll delve into the initial deployment, the shocking surprise attacks, and the incredible, against-all-odds repulse of the first Japanese landing attempt.

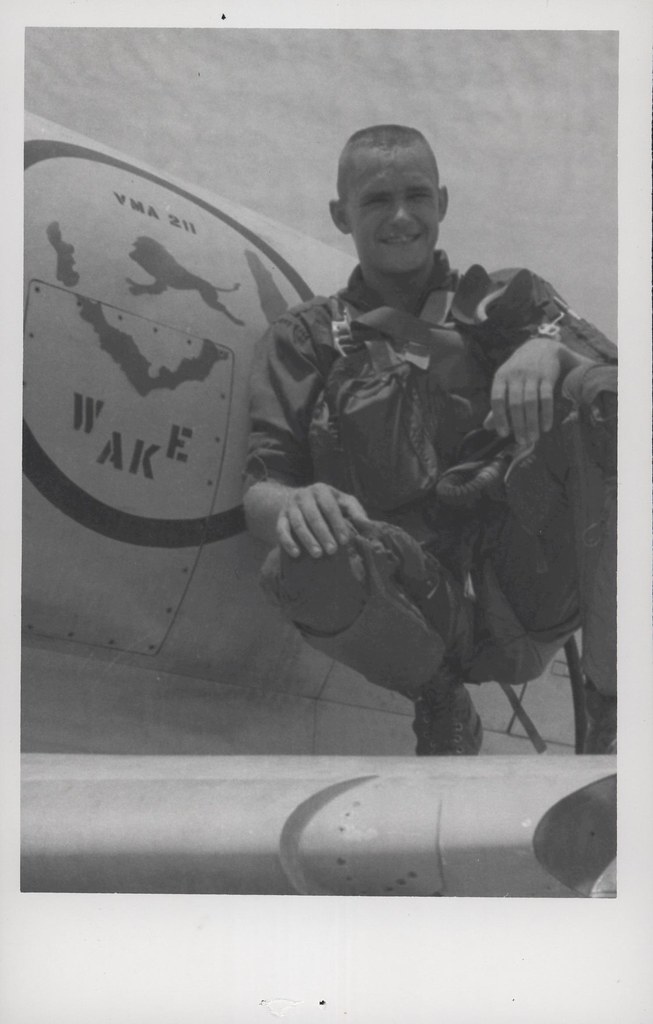

1. **Deployment to a Tiny Outpost**: In the tense days leading up to the fateful December of 1941, twelve F4F-3 Wildcats of VMF-211 were urgently dispatched to reinforce Wake Island. This tiny airstrip coral island served as a crucial stepping stone, a vital jumping-off point west from Hawaii into the vast South Pacific. Among the dedicated personnel was Captain Henry “Hammerin’ Hank” Elrod, a 36-year-old Marine veteran who had served in the Corps since 1927, transitioning from an infantryman to a Marine pilot in 1935.

Wake Island was more than just a refueling stop; it was a key component in American defensive strategy. The United States Navy had initiated construction of a military base on the atoll in January 1941, with the first permanent military garrison, elements of the 1st Marine Defense Battalion, deploying in August under Major J.P.S. Devereux. The island was bustling with approximately 1,221 civilian workers from the Morrison-Knudsen Civil Engineering Company, many of whom were veterans of massive dam projects, working to construct an airfield, a seaplane base, and a submarine channel.

Despite the diligent efforts, the defenses were far from complete. The relatively small size of the atoll meant the Marines couldn’t fully man all defensive positions, and they notably lacked crucial air search radar units. Their armament, while substantial for an outpost of its size, included six 5-inch guns salvaged from a World War I-era battleship, twelve 3-inch anti-aircraft guns with only a single working director, and a mix of Browning machine guns. On November 28, Commander Winfield S. Cunningham arrived to assume overall command, having just ten days to assess his command before war erupted.

2. **The Day Pearl Harbor Fell**: The tranquil morning of December 7th, 1941, on Wake Island, which was December 8th due to the International Date Line, quickly shattered. News arrived that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor, immediately catapulting the small Marine contingent on Wake into high alert. Four of the F4F-3 Wildcats, the island’s only airborne assets, took off on a combat air patrol, their pilots battling terrible visibility through thick clouds.

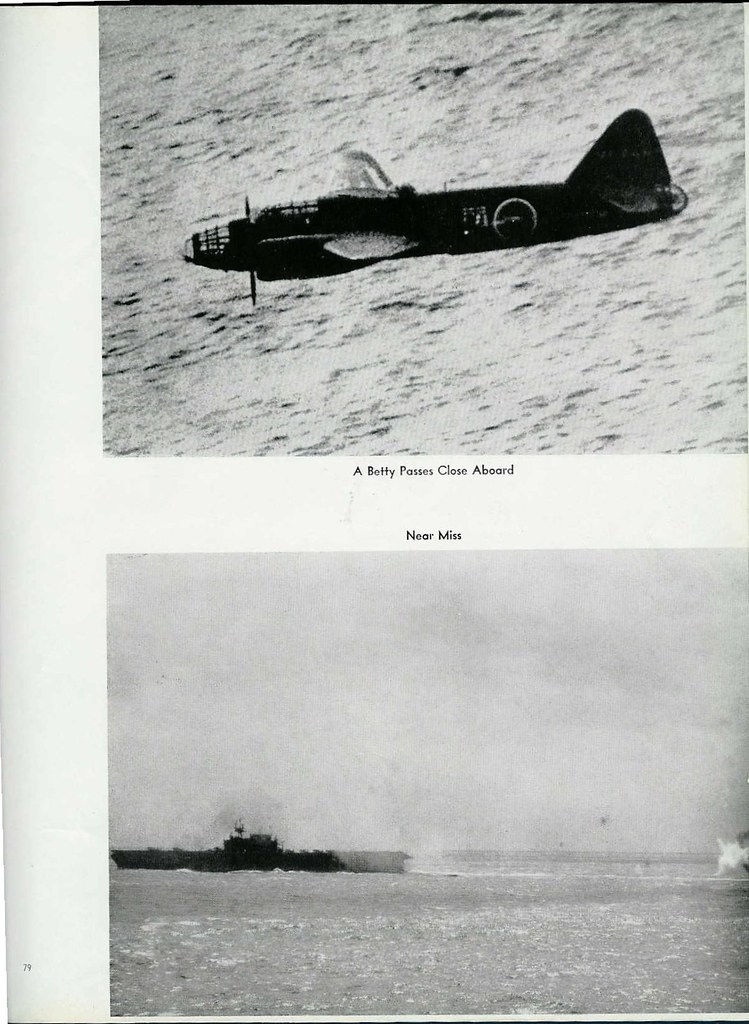

Just hours after the devastating attacks in Hawaii, these Wildcat pilots heard alarming reports of enemy bombers attacking Wake Island. Flying back overhead, they desperately searched the cloudy skies but found no trace of the attackers. The Japanese, specifically a full complement of 34 Mitsubishi G3M2 Type 96 Nells from the expert Chitose Air Group, had wasted no time. They had departed Roi airfield in the Marshalls, flying to Wake at 13,000 feet, and, just before noon, dove down to 1,500 feet for their bombing runs, surprising the base as they emerged from low-lying clouds, racing in from the sea.

This swift and brutal strike, a mere hours after the infamous Pearl Harbor attack, underscored the coordinated and far-reaching nature of the Japanese offensive. The geographical positioning of Wake Island meant that while the Pearl Harbor attack occurred on December 7th, the coordinated assault on Wake technically began on December 8th. This difference in time, however, did little to cushion the shock or mitigate the immediate, crushing impact of the surprise aerial onslaught.

3. **Devastation on the Tarmac**: Though the Wildcats, struggling with the poor visibility, failed to spot the enemy planes, the Japanese bombers had seen three of the Marine fighters before they wisely disappeared into the clouds for cover and escape. The returning Wildcat pilots were met with a horrifying sight upon landing: VMF-211’s flight line was engulfed in flames. It was a staggering blow, delivered with incredible precision by the Japanese raid.

The Japanese bombers, including G4M Betty bombers from the Marshall Islands, had executed their mission with devastating accuracy. Their bombs had annihilated all of the VMF-211 planes on the ground, leaving behind nothing but burning wreckage. Tragically, a number of the pilots who had attempted to scramble their aircraft during the raid were killed in the inferno. All that remained serviceable were the four F4F-3 Wildcats that had been fortunate enough to be airborne during the attack.

This initial raid had a profound impact beyond the material losses. Of the 55 Marine aviation personnel stationed on Wake, 23 were killed and 11 were wounded in this sudden onslaught. Additionally, nine Pan Am employees lost their lives, and many crucial buildings were destroyed, including those at the civilian hospital and the Pan Am air facility. The civilian survivors, along with some passengers, were quickly evacuated on the Martin 130 Philippine Clipper, which remarkably survived the attack, albeit with a few bullet holes.

4. **Relentless Bombings**: The Japanese were unrelenting in their assault on Wake Island, with two more air raids striking the island in the days immediately following the initial devastation. On December 9th, another bombing raid descended upon the island, this time with 27 Japanese Nell bombers. The surviving Wildcats valiantly rose to defend their beleaguered home, managing to damage twelve of the incoming enemy aircraft.

However, the relentless nature of these daily attacks continued to wrack havoc across the island. The main camp was systematically targeted on December 9th, leading to the destruction of the civilian hospital and the essential Pan Am air facility. The following day, December 10th, the enemy bombers shifted their focus, concentrating their destructive power on the outlying Wilkes Island.

A clever, though ultimately limited, defensive measure was taken after the December 9th raid: the four anti-aircraft guns were stealthily relocated in anticipation that the Japanese might have photographed their positions. Wooden replicas were erected in their place as decoys, which the Japanese bombers dutifully attacked. Unfortunately, a lucky strike on a civilian dynamite supply triggered a chain reaction, incinerating the precious munitions for the guns on Wilkes. Adding to the desperate situation, late on the night of December 10th, the submarine USS Triton, operating south of Wake, attempted to engage a Japanese destroyer, underscoring the grim readiness for the expected invasion.

5. **David vs. Goliath: Opposing Forces**: The approaching Japanese invasion fleet, aiming for Wake Island, presented an utterly formidable force, dwarfing the island’s meager defenses. It comprised no less than three light cruisers—the Yubari, Tenryuu, and Tatsuta—alongside six destroyers: the Yayoi, Mutsuki, Kisaragi, Hayate, Oite, and Asanagi. Additionally, two smaller Momi-class destroyer/patrol boats, No. 32 and No. 33, joined the fleet, alongside two armed merchant ships, the Kongo Maru and Kinryu Maru, which served as troop transports. These transports carried 450 elite Special Naval Landing Force soldiers, ready for an amphibious assault.

In stark contrast, the American defenses on the island were exceptionally thin. The ground forces consisted of just 450 Marines, bolstered by the 55 aviators and ground crewmen who made up the depleted VMF-211 fighter squadron. For coastal defense, the Marines possessed six 5-inch guns, salvaged from the World War I-era battleship USS Texas, augmented by twelve 3-inch anti-aircraft guns. A reasonable mix of Browning .50 cal and .30 cal machine guns provided additional firepower, yet against the might of the Japanese naval contingent, it was a truly desperate stand.

To put the disparity into perspective, a single Japanese light cruiser could easily outgun the entire island’s combined artillery. Nevertheless, the Americans still possessed their four remaining F4F-3 Wildcats, each armed with two 100-pound bombs mounted on their wings. As the battle commenced, these precious aircraft were manned by four courageous Marine pilots: Major Putnam led the quartet, with his executive officer, Captain “Hammering Hank” Elrod, and Captains Tharin and Freuler. The fourth Wildcat bravely took off just seven minutes before the Japanese ships unleashed their shells upon Wake.

6. **The First Repulsion: A Stunning Victory**: Early on the morning of December 11th, 1941, the American garrison on Wake Island, despite its limited resources, prepared for the inevitable. From a distance, as the Japanese invasion force rapidly closed in on the island, the naval vessels opened fire with everything they possessed. Shells began raining down across the beaches and inland onto the airfield, a preliminary bombardment designed to soften the defenses before the landing. The 450 Marines on the beach, however, stood firm and waited, holding their fire with steely resolve.

Inspired by the storied Battle of Concorde, their intention was to hold their fire until the enemy was within extremely close range, maximizing the impact of their limited ammunition. And they did so with spectacular success. At a range of just 4,000 yards, the Marines unleashed a torrent of fire from their six 5-inch guns. In an almost unbelievable display of precision gunnery, “Battery L,” strategically located on Peale Islet, scored direct hits on the destroyer Hayate.

The Japanese ship’s magazine was pierced by the accurate shellfire, leading to a catastrophic explosion that sent the vessel to the bottom of the sea within two minutes. This dramatic sinking unfolded in full view of the American defenders on shore, providing a massive morale boost. The Hayate became the first Japanese surface warship to be sunk in the war, a stunning testament to the skill and bravery of the Wake Island Marines and a significant, if temporary, setback for the Imperial Japanese Navy.

7. **Wildcat’s Fury: Elrod’s Bomb and the Kisaragi**: Following the unexpected retreat of the Japanese fleet, which had cancelled its landing attempt for the time being due to the devastating accuracy of the Marine shore batteries, the four F4F-3 Wildcats, which had formed up at 12,000 feet over Toki Point, realized there would be no combined Japanese air attack as on previous days. Instead, they watched as the battered Japanese ships withdrew from the island, a testament to the Americans’ unexpected tenacity.

Now, the four Wildcats, with their pilots brimming with defiance, dove fearlessly through a hail of anti-aircraft fire. It was an incredible spectacle: four lone planes against the combined AAA batteries of the 12 remaining warships of the “unlucky 13” that had dared to foray against the Americans on Wake Island. Each Wildcat carried just a pair of 100-pound light bombs, which were largely ineffective against most armored ships.

Yet, in this impossible scenario, Captain “Hammering Hank” Elrod aimed his bomb with deadly precision at the fantail of the Japanese destroyer Kisaragi and scored a direct hit, igniting intense fires. Though Elrod’s Wildcat was badly hit during subsequent strafing runs, he managed to heroically crash-land on the beach at Wake Island, his plane later scoured for spare parts. The remaining three Wildcats continued their relentless shuttle attacks against the Japanese ships. As they pressed one attack, they observed the Kisaragi, which Capt. Elrod had hit, suddenly explode as its depth charge stores, stowed in racks on the fantail, detonated. The explosion tore the stern off the destroyer, and like the Hayate, it sank immediately with the loss of all 167 Japanese sailors, a second stunning victory attributed to the Wildcats.

Even as the echoes of the first Japanese retreat faded, a new and perhaps even more poignant chapter of the Wake Island saga began to unfold. The stunning, if temporary, American victory on December 11th had galvanized a nation reeling from the shock of Pearl Harbor, providing a much-needed beacon of hope. Yet, the defenders of Wake knew their reprieve was fleeting; reinforcements were desperately needed, and fast, if they were to withstand the inevitable second assault.

8. **The Faltering Relief Effort: Task Force 14’s Ordeal**: News of Wake Island’s incredible defiance on December 11, 1941, brought a crucial surge of morale to the American public, offering a rare moment of good news amidst the grim realities of the Pacific War’s opening days. The small Marine and Navy force had repulsed an attempted Japanese amphibious assault, an almost unbelievable feat that saw two Japanese destroyers sent to the bottom of the sea. This gallantry, however, highlighted an urgent truth: the island’s defenders, despite their tenacity, were gravely exposed and required immediate reinforcement to survive.

In response to this pressing need, Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, then Commander-in-Chief of the United States Pacific Fleet, issued orders for Task Force 14 to embark on a vital relief mission. Comprising the aircraft carrier USS Saratoga and under the command of Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, the task force was tasked with ferrying essential supplies and a much-needed relief force to bolster the embattled garrison on Wake. On December 15th, just four days after Wake’s stunning victory, Task Force 14 departed Pearl Harbor, carrying the hopes of a nation on its decks.

However, the very next day, Kimmel was relieved of his command, plunging the nascent Pacific War into a period of uncertain leadership. The weighty responsibility of prosecuting the U.S. Navy’s war in the Pacific now fell, temporarily, to Vice Admiral William S. Pye. His flagship, the USS California, along with almost the entirety of the Pacific Fleet’s Battle Force, lay resting on the bottom of Pearl Harbor, a stark reminder of the devastating blows already suffered. The fate of Wake’s valiant garrison, and indeed the entire relief mission, now rested precariously in his hands, at a moment of profound vulnerability for the American fleet.

9. **Admiral Pye’s Burden: A Commander’s Conundrum**: Vice Admiral William S. Pye, a graduate of Annapolis in 1901, had earned a formidable reputation as one of the Navy’s finest strategic minds, even earning the Navy Cross for his “exceptionally distinguished” staff work during World War I. His stocky, pugnacious appearance made him seem more like a beat cop than a high-ranking admiral, projecting an image of toughness. Yet, as he assumed temporary command of the Pacific Fleet, questions lingered about whether he would truly act as tough as he looked, especially after the recent devastating events at Pearl Harbor.

Just days before the Pearl Harbor attack, on December 6th, Pye had expressed a remarkably optimistic, and ultimately incorrect, assessment of the geopolitical situation. When consulted by Admiral Kimmel’s intelligence chief regarding Japanese fleet movements, Pye confidently asserted, “The Japanese will not go to war with the United States. We are too big, too powerful, and too strong.” Less than twenty-four hours later, Pye found himself covered in oil, having just left his sinking flagship, and watching in horror as Japanese aircraft transformed the Pacific Fleet into burning wreckage. This stark contradiction between his prediction and reality profoundly shaped his subsequent command.

His appointment as temporary CINCPAC sent ripples of shock through the ranks, especially for those like intelligence chief Lt. Cmdr. Edwin T. Layton, who vividly recalled Pye’s ill-fated pre-war prediction. Pye, having previously dismissed the Imperial Japanese Fleet as a threat, now seemed to undergo a complete shift, exhibiting a marked reluctance to engage the enemy, particularly when intelligence reports mentioned “Japanese carrier” presence. Despite this newfound caution, Pye initially refrained from countermanding Task Force 14’s mission, even allowing a diversionary attack on the Japanese-held Marshall Islands by the carrier Lexington to proceed, but his apprehension was palpable and would soon have critical consequences.

10. **A Glimmer of Hope: The PBY’s Secret Orders and Civilian Evacuation Plans**: Amidst the daily Japanese aerial bombardments and the uncertainty of the relief mission, a brief, tantalizing glimmer of hope arrived on Wake Island on December 20, 1941. A PBY patrol bomber, defying the odds, landed with a precious delivery of mail, a small comfort in a besieged outpost. Upon its departure, it carried a single, significant passenger: Lieutenant Colonel Walter Bayler, who would later be known as the last Marine to leave Wake before its capture. Bayler’s extraction was strategic, as he possessed rare expertise in establishing air-ground communications networks and invaluable knowledge of the still top-secret U.S. radar program, skills deemed too vital to risk on the island.

Beyond mail and a high-value passenger, the PBY carried something far more crucial: secret orders for Commander Winfield Scott Cunningham, Wake’s overall commander. These orders directed him to begin preparing the majority of the civilian contractors for evacuation, offering a pathway to safety for the more than 1,200 civilian workers who had found themselves trapped in a war zone. The PBY also brought a detailed manifest of the equipment slated for delivery by the relief mission, including a much-needed radar unit, ammunition, and additional personnel, painting a picture of a revitalized defense.

Furthermore, the PBY’s visit allowed the beleaguered Wake Island staff to provide Pearl Harbor with a comprehensive and detailed account of the battle thus far, complete with crucial paperwork. This vital intelligence exchange was essential for the strategic planners attempting to coordinate the distant relief efforts. After a swift refueling, the PBY departed the following morning, December 21, 1941, carrying not only its additional passenger but also the burden of the island’s desperate hope for rescue. Unbeknownst to the Americans, this critical radio transmission from the PBY was intercepted by the Japanese, inadvertently signaling their urgency and prompting them to accelerate their plans for a second, decisive landing attempt.

11. **The Escalation: Japanese Carrier Air Strikes**: With the PBY’s departure, and the Japanese intercepting its vital radio transmissions, the Imperial Japanese Navy swiftly escalated its assault, no longer reliant solely on land-based bombers. On December 21st, a new, far more potent threat emerged from the horizon: a formidable Japanese carrier group, spearheaded by the aircraft carriers Hiryu and Soryu, moved within range of Wake Island. These carriers, fresh from their devastating success at Pearl Harbor, launched 49 aircraft against Wake, initiating a new and terrifying phase of the aerial bombardment that would systematically dismantle the island’s remaining defenses.

Following this initial carrier raid, a lone F4F Wildcat heroically launched an attempt to shadow the Japanese carrier planes back to their elusive base, while Wake’s commander urgently notified Pearl Harbor of the new, more significant threat. The aerial onslaught, however, continued relentlessly. Later that same day, an additional air raid, this time comprising 33 G3M2 Nells from the Japanese base on Roi, struck Wake, inflicting further casualties, killing a platoon sergeant and wounding several others, demonstrating the multi-pronged nature of the Japanese air offensive and the increasing intensity of their determination.

On December 22nd, the Japanese carrier air raid from the Hiryu and Soryu intensified, with 39 planes descending upon the island. The few remaining Wildcats rose to defend, but in the ensuing, brutally unequal air battle, both were shot down. One managed a crash landing back on the beach, a testament to the pilots’ incredible skill and tenacity, while the fate of the other remained unknown. Even Japanese Admiral Abe, commanding the carrier group, was reportedly impressed by the extraordinary courage displayed by these two Marine pilots, acknowledging their defiant bravery in the face of insurmountable odds. The arrival of these carriers marked a critical turning point, indicating that the Japanese had committed significant naval air power to crush Wake’s resistance once and for all.

12. **The Final Air Defiance: Wake’s Last Wildcats**: For nearly two weeks following the first invasion attempt, the Japanese air attacks remained unrelenting, a daily hammer blow against the dwindling American garrison. The ground crews, displaying remarkable ingenuity and perseverance, worked tirelessly, often cannibalizing damaged aircraft to keep just three, then ultimately only two, of the precious Wildcats flying. With no new supplies or spare parts reaching the besieged island, this desperate maintenance effort was a testament to their dedication, but it was a battle against attrition they could not win indefinitely.

On a particularly grim day, “Hammering Hank” Elrod, despite his earlier plane being scavenged for parts, rose alone in the one serviceable Wildcat to intercept an incoming force of 22 G3M2 Nells. Undaunted by the overwhelming numerical superiority, he flung his lone Wildcat into the Japanese formation, guns blazing. In two passes, he claimed two enemy planes, though Japanese records only confirm one loss that day. Despite the fierce resistance, the remaining Japanese bombers continued their attack, dropping their payloads, albeit with less accuracy than previous raids, demonstrating the disruptive effect of even a single, courageous defender.

By the morning of December 22nd, with the last four Wildcats now critically damaged or completely out of action, the Japanese Navy returned with an even more formidable force, including the two aircraft carriers, Soryu and Hiryu. They launched 39 planes against Wake in a final, decisive aerial assault. The last two American Wildcats, somehow still operational, bravely rose to meet them. In the brutal dogfight that ensued, both were shot down, though one managed to execute a final, heroic crash landing on the beach. This marked the absolute end of American air superiority, or even presence, over Wake Island, leaving the defenders entirely exposed to the coming ground assault.

13. **The Second Wave: Japan’s Decisive Amphibious Assault**: The initial, unexpected resistance by the Wake garrison on December 11th had forced the Imperial Japanese Navy to reassess their strategy, prompting a significant reallocation of forces. Recognizing the tenacity of the American defenders, they detached elements from the Second Carrier Division—the Sōryū and Hiryū, along with their escorts—all fresh from their triumph at Pearl Harbor. Additional cruisers and destroyers, originally assigned to invasions of Guam and the Gilbert Islands, were also redirected to bolster the Wake invasion force, creating an overwhelming concentration of naval power specifically to subdue the defiant atoll.

This vastly reinforced Japanese invasion fleet, composed largely of ships from the first attempt but now augmented by a fresh complement of 1,500 Japanese marines, descended upon Wake Island in the pre-dawn hours of December 23rd. Following a preliminary naval bombardment, which systematically pounded the island’s defenses, the Japanese began their landings at multiple points across the atoll at 02:35. This coordinated and overwhelming assault left no doubt as to the Japanese determination to secure the island at any cost.

As the Japanese pressed their advantage, their elite Special Naval Landing Force soldiers poured onto the beaches, immediately encountering the tenacious resistance of the remaining American defenders. Though significantly outnumbered and outgunned, the Marines on Wake Island fought with every ounce of their dwindling strength, transforming the landing zones into desperate battlefields. The sheer scale of the second assault, coupled with the precision of their preliminary bombardment, steadily wore down the remaining pockets of American resistance, setting the stage for the island’s inevitable fall.

14. **The Fall and Lingering Legacy: Wake Island’s Enduring Story**: Despite the heroic, almost miraculous, defense waged by the small American garrison, the sheer weight of Japanese numerical superiority and relentless pressure ultimately proved overwhelming. On December 23rd, after fierce fighting that had lasted since December 8th, Wake Island fell to the Empire of Japan, and the American forces were compelled to surrender. Approximately 90 percent of the defenders survived, many bearing injuries, and were subsequently evacuated off the island in small groups, destined for prisoner of war camps across Asia where most would endure the remainder of the war.

However, a particularly grim fate awaited a specific group of 98 civilian contractors. These men, who had tirelessly worked to construct the military facilities on the island, were tragically executed by the Japanese commander in October 1943 after being forced into slave labor. This heinous act would lead to the commander’s conviction and death sentence after the war, a stark reminder of the brutal realities of wartime captivity. Five other American POWs also perished, executed during their sea voyage to the distant camps.

Though taken by the Japanese, Wake Island never served its intended purpose as a forward operating base for an attack on Hawaii. The U.S. Navy, rather than attempting a costly recapture, opted instead for a strategic submarine blockade. Consequently, the Japanese garrison on the island spent the remainder of the war isolated, often ill-supplied and starving, subjected to constant Allied air attacks as Wake became a regular training mission for new aircraft and pilots arriving in the Pacific Theater. The island’s strategic value thus effectively nullified for the Japanese, it remained a lonely outpost of occupation until its final surrender to a detachment of United States Marines on September 4, 1945, days after Japan’s formal surrender in Tokyo Bay.

The Battle of Wake Island, though a tactical defeat, remains an indelible chapter in American military history. President Franklin Roosevelt, upon receiving news of its fall, reportedly deemed it “worse than Pearl Harbor,” a reflection of the deep sense of betrayal felt over the inability to relieve the garrison, and he never quite forgave Admiral Pye for the decision to abandon its defenders. For the Marine Corps, the sentiment was even stronger: they never forgave him either. Wake Island stands as a powerful testament to indomitable courage, a story of an impossible defense that, despite its tragic conclusion, electrified a nation and continues to inspire with its fierce, defiant spirit.