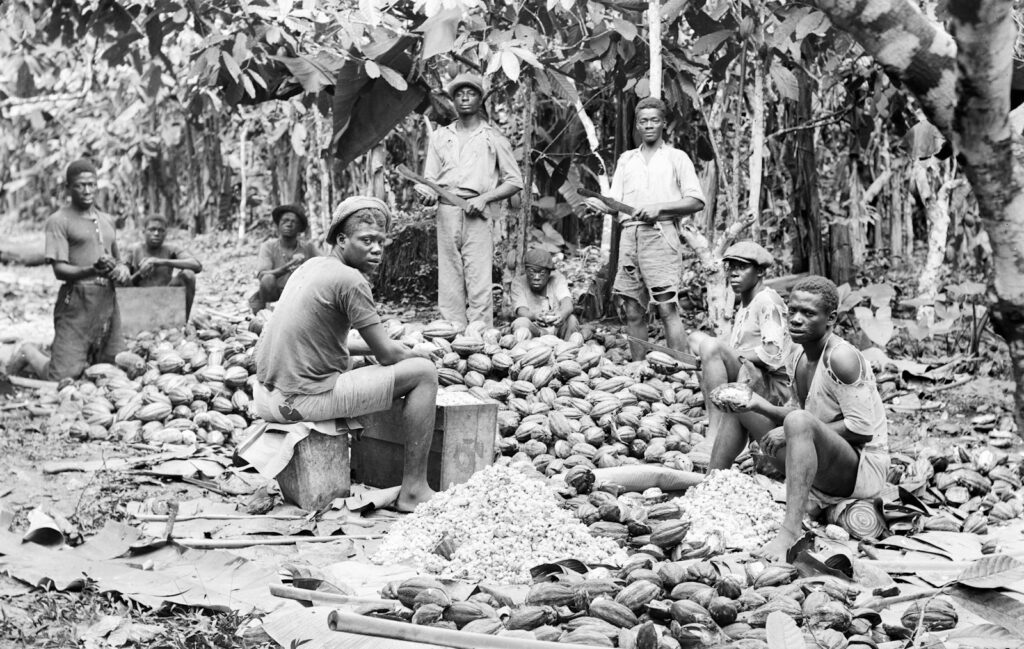

Toni Morrison’s 1987 novel Beloved represents a landmark in American literature, offering a searing, psychologically complex portrayal of slavery’s enduring trauma. Awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1988 and named a finalist for the 1987 National Book Award, the novel has become both a literary masterpiece and a critical document of American cultural memory. In a survey conducted by The New York Times, Beloved was ranked the greatest work of American fiction published between 1981 and 2006, affirming its central place in the literary canon.

Set in the years following the American Civil War, the narrative centers on a family of formerly enslaved individuals in Cincinnati, whose home is haunted by a vengeful and disruptive spirit. Morrison weaves historical reality with psychological depth, drawing powerful inspiration from the true story of Margaret Garner, an enslaved woman who fled Kentucky for Ohio in 1856 in pursuit of freedom.

Garner’s desperate flight and its tragic consequences serve as the emotional core of Beloved. After being discovered by U.S. marshals acting under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Garner attempted to kill her children rather than see them returned to slavery. She succeeded in ending the life of her youngest daughter. Morrison based this pivotal event on an 1856 article titled “A Visit to the Slave Mother who Killed Her Child,” originally published in the American Baptist and later included in The Black Book, a historical anthology Morrison edited in 1974. The novel’s fictional world emerges from this harrowing account, confronting readers with the psychological toll of slavery and the desperate choices it forced upon the oppressed.

A Haunted Home and a Buried Past: The Supernatural Fabric of Beloved

The novel’s underlying grief is immediately evident in its dedication: “Sixty Million and more.” This solemn invocation references the countless Africans and their descendants who perished due to the transatlantic slave trade. Morrison deepens the thematic resonance through an epigraph from Romans 9:25 in the King James Bible: “I will call them my people, which were not my people; and her beloved, which was not beloved.” These lines signal a meditation on identity, belonging, and the inescapable imprint of history, inviting readers into a space where life and death, love and loss, are inextricably entangled.

The story begins in 1873 at 124 Bluestone Road in Cincinnati, Ohio. Sethe, a formerly enslaved woman, lives there with her 18-year-old daughter, Denver. Their house has long been plagued by what they believe to be the ghost of Sethe’s eldest daughter, a presence so oppressive it drove away Sethe’s sons, Howard and Buglar, by the age of thirteen. Baby Suggs, Sethe’s mother-in-law and the mother of her husband Halle, died eight years earlier, not long after the boys’ departure. Since then, Sethe and Denver have lived in near-complete isolation.

This fragile domestic existence is disrupted by the arrival of Paul D, a man who was enslaved alongside Sethe, Halle, and Baby Suggs at Sweet Home, the plantation they once called home. His reappearance brings temporary relief. He manages to banish the malevolent spirit, although Denver resents his intrusion, having come to view the ghost as her only source of companionship. Paul D eventually convinces Sethe and Denver to attend a carnival, offering a brief but meaningful glimpse of life beyond their haunted walls.

Shortly after their return, a mysterious young woman appears outside the house, drenched and seemingly emerging from a body of water. She introduces herself as Beloved. Although Paul D is wary and urges caution, Sethe becomes enthralled by her presence and disregards his warnings. Denver, longing for connection, swiftly accepts Beloved and becomes convinced she is her deceased sister returned from the grave.

The Weight of Memory: Trauma, Guilt, and the Collapse of Self in Beloved

Beloved’s presence exerts a deep and unsettling influence over the household at 124 Bluestone Road, gradually pushing Paul D into a state of psychological distress. One night, she confronts him and demands that he touch her “on her inside part.” The resulting sexual encounter forces Paul D to relive suppressed memories of his past, including the sexual violence he and others endured while imprisoned in a chain gang. Unable to express the magnitude of his trauma, he instead suggests to Sethe that they have a child together—a proposal that reawakens her fears of living for the sake of another baby.

When word of Paul D’s intentions reaches his co-workers, they respond with alarm, driven by a hidden truth in Sethe’s past. Stamp Paid, a longtime friend, reveals the source of the community’s rejection by showing Paul D a newspaper clipping about a fugitive woman who had killed her child. Confronted with the evidence, Sethe recounts the painful truth.

She explains that after her escape from slavery and reunion with her children, four men—agents of her former enslavers—arrived at 124 to reclaim them. Fearing a return to Sweet Home and to the brutal authority of Schoolteacher, Sethe took her children to the woodshed. Intending to save them from re-enslavement, she attempted to kill them all, but succeeded only in ending the life of her eldest daughter. Sethe insists that her actions were rooted in love, declaring that she was “trying to put my babies where they would be safe.” Paul D, however, cannot accept this rationale. He accuses her of loving “too thick” and warns, “You’ve got two feet, not four.” Sethe defends her decision with resolute clarity: “Thin love is no love.”

Her belief that Beloved is the reincarnation of the daughter she lost becomes all-consuming. The name “BELOVED,” the only word Sethe could afford to have engraved on the child’s tombstone, strengthens this conviction. Sethe becomes convinced that Halle and her sons will return, and she envisions a restored family. Driven by guilt, she devotes all her time and remaining financial resources to pleasing Beloved and validating her past choices. She loses her job and descends into physical and emotional exhaustion.

Meanwhile, Beloved’s behavior grows increasingly erratic and domineering. Her emotional demands multiply, and her presence overwhelms the household. As Sethe begins to waste away from neglect, Beloved inexplicably grows in size, eventually appearing to be pregnant, a manifestation of the psychological weight she embodies.

Healing and Memory in the Final Act of Beloved

Denver, who has always known that her mother killed Beloved but never fully grasped the motivation behind it, begins to sense the intensifying threat. She recalls that her brothers fled because of their shared fear of Sethe. As Beloved’s hold on the household grows, the psychological boundaries between mother and daughter disintegrate. Their voices blend into an indistinct chorus, and Denver observes a disturbing transformation: Sethe begins to behave like a child, while Beloved assumes a dominant, maternal presence, distorting the balance within the home.

Recognizing the need for intervention, Denver steps beyond the confines of 124 Bluestone Road and reconnects with the broader Black community. For years, the family had been shunned, partly due to resentment over Baby Suggs’s former spiritual prominence, and partly due to the collective horror at Sethe’s act of infanticide. Moved by Denver’s plea, a group of local women gathers at the house with the intention of casting out the malevolent presence.

At the same moment, Mr. Bodwin, their White landlord, arrives to offer Denver a job, unaware of the spiritual crisis unfolding within. Sethe, disoriented by Beloved’s influence and mistaking Bodwin for the returning Schoolteacher, attacks him with an ice pick. The village women and Denver manage to restrain her, and in the midst of the chaos, Beloved disappears without explanation.

In the aftermath of her vanishing, Denver embraces her renewed ties with the community and begins to build a life of purpose and independence. Paul D later returns and finds Sethe confined to bed, emotionally broken by Beloved’s absence. In a moment of quiet regret, Sethe describes Beloved as her “best thing.” Paul D gently corrects her, affirming that Sethe herself is her “best thing.” This exchange prompts Sethe’s stunned reply: “Me? Me?”

Over time, those who once knew Beloved begin to forget her. Her presence fades from collective memory, leaving behind a lingering stillness that serves as both resolution and elegy.

Exploring Identity and Trauma: Motherhood, Slavery’s Psychological Legacy, and Masculinity in Beloved

At its core, Beloved offers a profound examination of mother-daughter relationships, revealing how maternal bonds—especially under the brutal conditions of slavery—can hinder a woman’s individuation and provoke dangerous passions. Sethe’s extreme act, motivated by the desire to protect her “fantasy of the future”—her children—from the horrors of enslavement, underscores the devastating impact on both mother and child. The novel portrays Sethe’s trauma, exemplified by the theft of her milk, which disrupts the symbolic bond of nurturing, while Denver’s eventual engagement with the wider community marks her passage into womanhood. Sethe attains true individuation only after Beloved’s exorcism, freeing her to embrace a relationship with Paul D that is centered on her own needs, releasing her from self-destructive patterns rooted in overwhelming maternal ties.

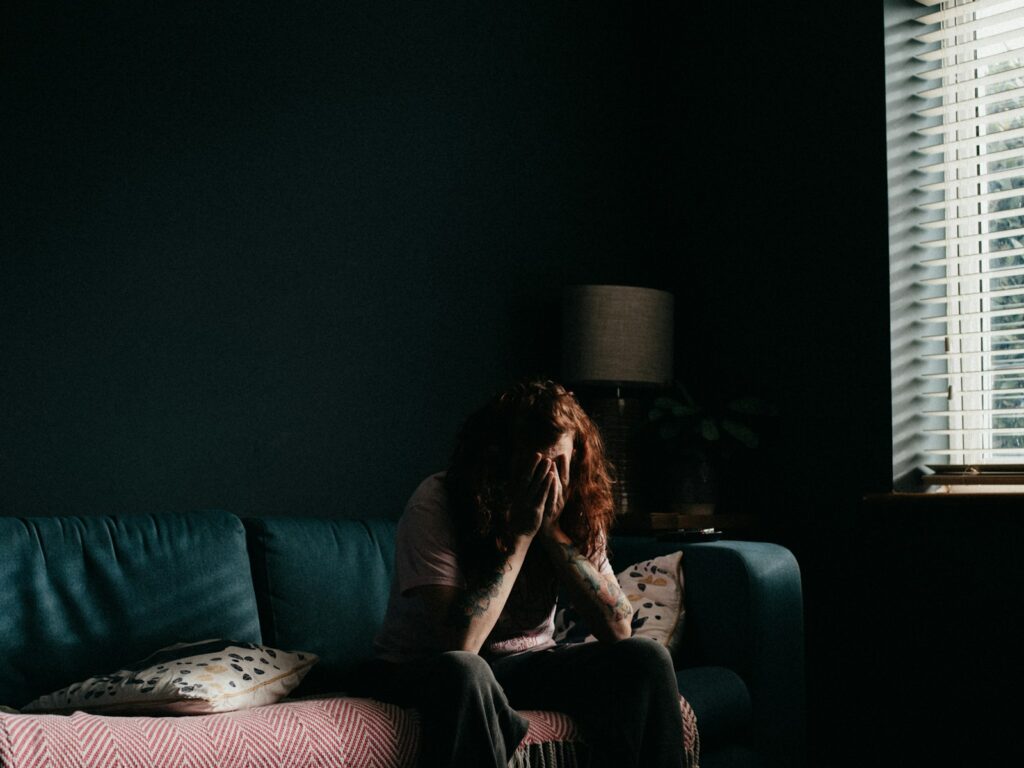

Another central theme is the psychological legacy of slavery. Morrison depicts how most former slaves coped by repressing painful memories, leading to fragmentation of self and loss of authentic identity. Sethe, Paul D, and Denver each contend with this fractured sense of self, which can only be restored through confronting and reconciling with their pasts and memories. Beloved functions as a haunting embodiment of repressed trauma, compelling these characters to face their pain and ultimately reintegrate their fractured identities. Slavery, Morrison suggests, creates a “self that is no self,” a condition where identity—composed of painful memories and unspeakable experiences—is denied and suppressed. Healing thus requires articulating these experiences, reorganizing narratives, and humanizing the past to reclaim one’s selfhood. The characters’ fear of memory and entering “a place they couldn’t get back from” highlights their struggle to reconstruct identity.

Morrison further explores the complex definition of manhood, particularly its distortion under slavery. Stylistically, she conveys the profound impact of enslavement on Black masculinity, centering on Paul D’s struggle. His conception of manhood is continuously challenged by the dominant white cultural norms. Despite his sacrifices and lofty aspirations, racism renders his goals tragically unattainable. Morrison’s use of “half-formed words and thoughts” expresses his internal conflict, portraying a masculinity diminished by a discourse that dehumanizes Black men. During Reconstruction and the Jim Crow era, Black men like Paul D were forced to forge identities within severe social constraints. Stamp Paid’s observation of Paul D as “stripped of the very maleness that enables him to caress and love the wounded Sethe” metaphorically positions Black men as foundational yet exploited members of society, deemed “lower-status” due to their skin color.

Fractured Families, Universal Pain, and Redefined Heroism in Beloved

Family relationships are depicted as both essential and tragically dismantled by the system of slavery, which denied African Americans autonomy over themselves, their children, and their possessions. Sethe’s act of killing Beloved is portrayed as a “peaceful act,” a desperate conviction that death offered salvation from the horrors of re-enslavement. This irreversible act fractures her family, reflecting the widespread brokenness experienced by formerly enslaved families in the aftermath of the Emancipation Proclamation. The novel also emphasizes the deep reliance formerly enslaved people placed on the supernatural, through rituals and prayers, as a response to exclusion from mainstream society. Beloved’s haunting of Sethe symbolizes these fractured familial bonds and the profound psychological torment endured by the protagonist.

The universality of pain permeates Beloved, affecting every character scarred by slavery on physical, mental, social, and psychological levels. Morrison illustrates how characters attempt to romanticize their suffering, transforming trauma into pivotal moments, a theme resonant with early Christian contemplative traditions and African-American blues culture. The narrative itself is a complex maze, representing how characters were stripped of their voices, stories, and language, diminishing their sense of self. Despite sharing the experience of slavery, each character’s suffering is unique and deeply personal.

Pain, however, is often aestheticized in ways that paradoxically soften its horror. For instance, Sethe recounts a white girl’s description of her back scars as “a Choke-cherry tree. Trunk, branches, and even leaves,” implying a search for beauty amidst immense suffering—a notion Paul D and Baby Suggs reject with revulsion. Similarly, Sethe accepts Beloved into her home as a living presence rather than as a manifestation of the pain of murder, despite Paul D and Baby Suggs’ reservations. The novel concludes with Paul D encouraging Sethe to love herself, affirming that she is her own “best thing,” coinciding with Beloved’s departure.

Morrison redefines heroism in Beloved as relative rather than absolute, shaped by past experiences and community context. Sethe emerges as an unlikely hero, one who empowers those she loves to break free from their traumatic pasts. Her controversial decision to kill Beloved, though condemned by the community, remains justified in her own eyes: “It ain’t my job to know what’s worse. It’s my job to know what is and to keep them away from what I know is terrible. I did that.” This defiance of societal norms and prioritization of her children’s freedom, even in death, exemplifies her unique form of heroism. Furthermore, Sethe’s support enables Paul D to confront his own traumatic past, particularly the iron bit incident, helping him preserve his “manhood” by never discussing or acknowledging his scars.

Resilience and Redemption: Key Characters in Toni Morrison’s Beloved

Denver transcends the limitations of her isolated past, embodying her own form of heroism by rescuing Sethe from Beloved’s consuming parasitism. Her decisive choice to “leave the yard; step off the edge of the world, leave the two behind and go ask somebody for help” demonstrates remarkable courage in breaking free from seclusion. This act enables her to challenge societal perceptions and inspire her mother to envision a future beyond the shadows of their past. Denver’s maternal resolve motivates Ella to rally community women in an exorcism of Beloved, producing a “wave of sound” that cleanses Sethe “like the baptized.” Morrison’s portrayal of Sethe and Denver underscores that true heroism lies not in supernatural feats but in the determination to overcome societal constraints and liberate oneself and others from the burdens of history.

Each major character in Beloved contributes to the complex tapestry of suffering and resilience. Sethe, the protagonist, is marked by her traumatic history as an enslaved woman from Sweet Home, symbolized by the “tree on her back”—her whipping scars. Her unwavering maternal instinct, even to the point of infanticide, shapes her resilient yet haunted persona. Beloved, the mysterious young woman emerging from the water, is widely accepted as the murdered infant whose return ends the haunting of 124. Morrison has confirmed that Beloved is the deceased daughter, her name taken from the inscription on the tombstone. Beloved acts as a catalyst, bringing repressed family trauma to the surface while also draining Sethe’s vitality and sanity.

Paul D, who retains his enslaved name, carries a “tobacco tin” for a heart—a metaphor for his suppressed painful memories that Beloved forces open. His reunion with Sethe ignites a romantic connection, though he struggles to fully comprehend her complex maternal experience due to years apart and his own deep-seated trauma. Denver, Sethe’s only remaining child at 124, evolves from an isolated, immature figure into a protective woman. She forms a profound bond with her mother yet recognizes Beloved’s destructive influence, ultimately striving for independence and safeguarding Sethe’s welfare, thereby breaking the cycle of isolation at 124. Denver is eighteen years old at the novel’s outset.

Baby Suggs, Sethe’s mother-in-law, gained freedom through the labor of her son Halle and became a revered spiritual leader within the Cincinnati Black community, preaching self-love. Her influence waned following a community feast that incited envy and Sethe’s infanticide that caused horror; she subsequently withdrew from public life, contemplating colors until her death at seventy. Halle, Sethe’s husband, appears only in flashbacks and is presumed to have suffered mental breakdown after witnessing Sethe’s abuse at Sweet Home. Schoolteacher personifies the cruelty of slavery, dehumanizing enslaved people as animals. Amy Denver, a compassionate young white woman, provides a crucial moment of humanity by assisting the heavily pregnant Sethe to safety and delivering her daughter, who is named Denver in gratitude.

The Enduring Impact and Controversy Surrounding Toni Morrison’s Belove

Beyond its literary acclaim, Beloved has expanded its influence through adaptations in other media. The novel was adapted into a 1998 film directed by Jonathan Demme, notably produced by and starring Oprah Winfrey. In January 2016, BBC Radio 4 broadcast a ten-episode adaptation as part of its 15 Minute Drama series, skillfully adapted by Patricia Cumper, further embedding the story into cultural awareness.

The novel’s profound legacy extends into real-world remembrance and activism. Upon receiving the Frederic G. Melcher Book Award in 1988, Morrison remarked that “[t]here is no suitable memorial or plaque or wreath or wall or park or skyscraper lobby” honoring those enslaved. She added, “There’s no small bench by the road. And because such a place doesn’t exist (that I know of), the book had to.” Inspired by her words, the Toni Morrison Society launched the “bench by the road” project, placing commemorative benches at significant American sites connected to slavery. The first bench was dedicated on July 26, 2008, at Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina, a primary entry point for approximately 40% of enslaved Africans brought to the United States, a moment Morrison described as “extremely moved.” By 2017, the twenty-first bench was installed at the Library of Congress, honoring Daniel Alexander Payne Murray, the first African-American assistant librarian of Congress.

Despite widespread recognition and numerous awards, Beloved has faced considerable controversy and censorship. The novel has been banned in numerous U.S. schools, including at least eleven during the 2021–2022 academic year, with common objections citing “bestiality, infanticide, sex, and violence.” A notable incident occurred in 2007 at Eastern High School in Louisville, Kentucky, where the principal abruptly removed the book from an Advanced Placement English class following a parent’s complaint regarding language on page 13. Strong protests from the English teacher, supported by colleagues and alumni, reversed the ban, allowing the novel to remain part of the curriculum.

Beloved endures as a powerful and vital narrative that resists the erasure or simplification of the past. Through its unflinching examination of the psychological scars of slavery, intricate exploration of identity and memory, and the human spirit’s capacity for profound suffering and resilience, Toni Morrison created more than a novel. She constructed a literary monument honoring the silenced lives and legacies of millions, serving as a beacon that illuminates the complex and often painful truths of American history. This work compels readers to remember, question, and confront the deepest aspects of shared humanity, ensuring that the voices of the “Sixty Million and more” continue to resonate across generations and remain indelibly etched into collective consciousness.