In the vast landscape of American literature, few novels resonate with the profound depth and unwavering intensity of Toni Morrison’s 1987 masterpiece, *Beloved*. This seminal work, set in the harrowing period following the American Civil War, plunges readers into the heart of a dysfunctional family of formerly enslaved people whose Cincinnati home is haunted by a malevolent spirit, forever entwined with the brutal legacies of their past.

*Beloved* quickly garnered significant critical acclaim upon its release, earning the prestigious Pulitzer Prize for Fiction a year after its publication and standing as a finalist for the 1987 National Book Award. Its literary prowess was further solidified when a survey of writers and literary critics compiled by The New York Times subsequently ranked it as the best work of American fiction from 1981 to 2006. More than just a story, it is a vital act of remembrance, a powerful testament to the lives and struggles often erased from conventional historical narratives.

The genesis of this haunting narrative lies in the grim reality of history, drawing its core inspiration from the life of Margaret Garner. Garner was an enslaved person in the enslaving state of Kentucky who, in 1856, made a desperate escape to the free state of Ohio. Under the draconian Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, she was subject to recapture, and when U.S. marshals violently breached the cabin where she and her children had barricaded themselves, she was discovered in the tragic act of attempting to kill her children, having already taken the life of her youngest daughter, in a desperate bid to spare them from the unspeakable horror of being returned to slavery.

Morrison’s main inspiration for recounting this agonizing historical episode was an account titled “A Visit to the Slave Mother who Killed Her Child.” This 1856 newspaper article, initially published in the American Baptist, was reproduced in *The Black Book*, an anthology of texts of Black history and culture that Morrison herself had edited in 1974. Through this historical lens, Morrison crafted a narrative that not only recounts a personal tragedy but also illuminates a collective trauma, giving voice to the silenced millions.

Indeed, the novel’s dedication, “Sixty Million and more,” serves as a poignant and powerful reference to the estimated number of Africans and their descendants who perished as a direct result of the Atlantic slave trade. This dedication immediately establishes the monumental scope of the suffering the novel seeks to address. Furthermore, the book’s epigraph, drawn from Romans 9:25 of the King James Bible, states: “I will call them my people, which were not my people; and her beloved, which was not beloved,” subtly foreshadowing the complex themes of identity, belonging, and profound loss that permeate the story.

The narrative unfolds in 1873 in Cincinnati, Ohio, focusing on Sethe, a formerly enslaved woman, and her 18-year-old daughter, Denver, living in a house known simply as 124 Bluestone Road. This residence has been plagued for years by what they believe is the ghost of Sethe’s eldest daughter. Denver, isolated and shy, finds her only companion in this spectral presence. Sethe’s two sons, Howard and Buglar, had fled the home by the age of 13, a departure Sethe attributes to the malevolent ghost’s influence. Baby Suggs, Sethe’s mother-in-law and the matriarch of the family, had passed away eight years prior, shortly after the boys’ departure.

Read more about: Toni Morrison’s Beloved: A Haunting Legacy of Memory, Motherhood, and Resistance

The fragile quiet of 124 is disrupted one day by the arrival of Paul D, one of the enslaved men from Sweet Home, the notorious plantation where Sethe, Halle, Baby Suggs, and others were once held captive. Paul D, with his grounded presence, manages to force out the troublesome spirit, an act that earns him Denver’s initial resentment for driving away her sole companion. Yet, his arrival brings a fragile hope, persuading Sethe and Denver to venture out together for the first time in years, to experience the simple joy of a carnival.

Upon their return, a young woman identifying herself as Beloved is found sitting in front of the house. Paul D immediately harbors suspicion, warning Sethe of an unsettling aura, but Sethe, perhaps drawn by an inexplicable pull, is charmed by the newcomer and chooses to disregard his apprehension. Denver, meanwhile, embraces the sickly Beloved with eagerness, convinced that this mysterious woman is, in fact, her older sister, returned from the grave.

As Beloved’s presence strengthens, Paul D experiences growing discomfort, feeling increasingly marginalized and driven from the house. One night, Beloved corners Paul D, compelling him to touch her “inside part.” This deeply unsettling encounter triggers a torrent of horrific memories for Paul D, flooding his mind with the brutal sexual violence he and other men endured during their time in a chain gang. He attempts to confide in Sethe but finds himself unable to articulate the full horror, instead expressing a desire to make her pregnant, a prospect that fills Sethe with a renewed sense of fear regarding the burdens of a new life.

The community’s long-standing ostracization of Sethe becomes painfully clear when Paul D confides his plans to friends at work, who react with fear and rejection. Stamp Paid, a respected figure in the community, reveals the devastating reason for this isolation by presenting Paul D with a newspaper clipping detailing the story of a fugitive woman who killed her child. This revelation forces Paul D to confront Sethe, who then unveils the unspeakable truth of that fateful day.

Read more about: Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’: A Profound Examination of Slavery’s Enduring Scars and the Pursuit of Self

Sethe recounts how, after her harrowing escape and reunion with her children at 124, four horsemen arrived, intent on dragging her and her children back into the clutches of slavery at Sweet Home and under the cruel dominion of its manager, Schoolteacher. Consumed by terror at the thought of returning to that hellish existence, Sethe ran to the woodshed with her children, intending to kill them all, believing it was the only way to save them. She tragically succeeded only in killing her eldest daughter, asserting that she was “trying to put my babies where they would be safe.” Paul D, shattered by this confession, leaves, telling Sethe her love is “too thick” and chastising her, “you’ve got two feet, not four.” Sethe, unwavering in her conviction, defiantly retorts that “thin love is no love.”

In the wake of this raw confrontation, Sethe becomes convinced that Beloved is indeed the daughter she had killed, a belief fueled by the fact that “BELOVED” was all she could afford to have engraved on the nameless baby’s tombstone. Overjoyed, she clings to a fragile hope that Halle and her sons will return, and they can finally be a complete family. Consumed by guilt and a desperate need to atone, Sethe begins to pour all her time and dwindling money into Beloved, striving to please her and explain her past actions, ultimately leading to the loss of her job. Beloved, however, transforms into an increasingly angry and demanding presence, throwing tantrums when her desires are not met. Her influence becomes parasitic, consuming Sethe’s life. Sethe hardly eats, while Beloved grows larger and larger, eventually taking on the unsettling form of a pregnant woman.

Denver, observing this disturbing devolution, finally reveals her deep-seated fear of Sethe, having known that her mother killed Beloved but never truly understanding why. She confirms that her brothers shared this fear, leading to their flight from home. The voices of Sethe and Beloved gradually merge, becoming indistinguishable, as Denver observes Sethe regressing into a childlike state, while Beloved assumes a more maternal role. This chilling dynamic prompts Denver to finally seek help from the wider Black community, a community from which they had been isolated due to envy of Baby Suggs’s past privilege and the profound horror at Sethe’s act of infanticide.

Read more about: Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’: A Profound Examination of Slavery’s Enduring Scars and the Pursuit of Self

In a climactic moment, local women from the community arrive at the house to perform an exorcism of Beloved. Simultaneously, their White landlord, Mr. Bodwin, appears, intending to offer Denver a job, a request Denver had previously made to him. Mistaking him for Schoolteacher, returning to reclaim her daughter, Sethe attacks Mr. Bodwin with an ice pick. The village women and Denver restrain her, and in the ensuing chaos, Beloved mysteriously disappears. Denver, having bravely broken the cycle of isolation, becomes a working member of the community. Paul D eventually returns to a bed-ridden Sethe, who, devastated by Beloved’s disappearance, remorsefully confesses that Beloved was her “best thing.” Paul D, with tender wisdom, counters that Sethe is her own “best thing,” leaving her with the poignant, questioning thought, “Me? Me?” As time marches on, those who knew Beloved gradually forget her, until all traces of her presence have vanished, leaving only faint, lingering echoes of a painful past.

Morrison masterfully weaves several profound themes throughout *Beloved*, creating a tapestry of human experience under the crushing weight of slavery. Central among these is the exploration of **mother-daughter relationships**, revealing how the traumatic circumstances of slavery distorted and often tragically inhibited maternal bonds. Sethe’s “dangerous maternal passion” is a direct consequence of her desperate attempt to salvage her “fantasy of the future,” her children, from the horrors of enslavement, leading to the unthinkable act of killing one daughter. The novel also delves into how Sethe’s own individuation was stifled by these bonds, only fully beginning after Beloved’s exorcism, allowing her to embrace a relationship truly “for her” with Paul D. The psychological scars of slavery are further underscored by Sethe’s inability to form the symbolic bond of feeding her child, having had her milk stolen.

The **psychological effects of slavery** form another critical thematic pillar. The novel powerfully illustrates how the immense suffering under slavery compelled many formerly enslaved individuals to repress painful memories in an effort to simply survive. This repression and dissociation from the past, Morrison argues, lead to a fragmentation of the self and a profound loss of true identity. Characters like Sethe, Paul D, and Denver are depicted as having suffered such a loss, with healing and self-reintegration only possible when they confront and reconcile their pasts. Beloved, in her enigmatic presence, serves as a catalyst, forcing these characters to confront their deeply buried “rememories,” eventually leading to the reintegration of their fragmented selves. Morrison emphasizes that to heal and humanize, one must translate these painful events into language, reorganize them, and retell them, acknowledging that the “self” is located in a word and defined by others.

The **definition of manhood** is critically examined through the character of Paul D. Morrison meticulously explores how the institution of slavery distorted a man’s sense of self, revealing different pathways to understanding masculinity through Paul D’s half-formed thoughts and internal struggles. His perception of manhood is constantly challenged by the dominant norms and values of white culture, highlighting the stark distinctions between Western and African values. Scholar Zakiyyah Iman Jackson notes Paul D’s reduced manhood emerges in relation to a discourse of animality, reflecting how racism created insurmountable barriers to his dreams and goals. The novel illustrates how, in the post-Reconstruction era, Jim Crow laws further constrained Black men, forcing them to forge identities within a society that deemed them “lower-status,” even as their “hard labor” served as the very foundation of the white-dominant society.

Read more about: Toni Morrison’s Beloved: A Haunting Legacy of Memory, Motherhood, and Resistance

**Family relationships** are depicted as being under immense stress and dismantlement due to the systemic abuses of slavery. The institution denied enslaved individuals fundamental rights to themselves, their families, and their children. Sethe’s tragic act of killing Beloved is presented within this context as a desperate, “peaceful act” to save her daughter from an unspeakable fate. This extreme measure, however, fragments her family, mirroring the brokenness of the era. The novel also touches on the formerly enslaved community’s reliance on the supernatural, born from their exclusion from societal events, as they put their faith and trust in rituals and prayers.

**Pain** permeates the entire narrative, universal to every character scarred by slavery—physically, mentally, sociologically, and psychologically. Morrison explores how some characters, like Sethe, attempt to “romanticize” their pain, seeking beauty even in the grotesque. Sethe repeatedly describes her whip scars as “a Choke-cherry tree. Trunk, branches, and even leaves,” a description that evokes disgust from Paul D and Baby Suggs, highlighting her complex psychological coping mechanism. The novel portrays memory, grief, and spite as inextricably linked, as exemplified by Beloved’s unsettling presence in the home, a place of vulnerability where Sethe initially prefers a perceived living daughter over the painful memory of murder. Ultimately, Paul D encourages Sethe to turn her love inward, asserting that she is her own “best thing.”

Morrison also explores the nuanced concept of **heroism**, suggesting it is not absolute but relative to past experience and community influence. Sethe’s decision to kill her child, though scorned by the community, is presented as an act of profound, if tragic, heroism from her perspective. She justifies her actions with an unwavering conviction: “It ain’t my job to know what’s worse. It’s my job to know what is and to keep them away from what I know is terrible. I did that.” This challenges societal norms, positing that for Sethe, death was preferable to the return to enslavement. Sethe’s heroism also extends to her capacity to help Paul D confront his own past trauma, particularly the deep psychological scars left by the iron bit, symbolized by his “neck jewelry.” Paul D observes that “Only this woman Sethe could have left him his manhood like that. He wants to put his story next to hers,” highlighting her unique ability to foster healing without judgment.

Read more about: Unlocking Life’s Profound Truths: 14 Essential Lessons People Learn Too Late, But You Don’t Have To

Denver, initially a timid and isolated figure, emerges as another form of hero. Trapped by her isolation at 124 Bluestone Road, she finds the courage to break free from her self-imposed confinement, realizing “She would have to leave the yard; step off the edge of the world, leave the two behind and go ask somebody for help.” This act of stepping into the unknown to seek aid is a monumental leap, allowing her to rewrite the narrative of her isolation and her mother’s past. Her actions, in turn, inspire Ella and other community women to gather and collectively exorcise Beloved, creating a “wave of sound” that washes over Sethe, metaphorically cleansing her. Morrison suggests that heroism lies in the courageous intent to overcome societal preconceptions and positively influence others, freeing them from the burdens of the past.

Beyond its thematic richness, *Beloved* is populated by a cast of indelible characters, each meticulously crafted. **Sethe**, the protagonist, is a resilient figure defined by her traumatic past, marked literally by the “tree on her back” — the scars from her brutal whipping. Born in 1836, she was 19 when Denver was born. Her unwavering maternal instinct drives her, even to the point of infanticide, to protect her children from the abuses she endured. **Beloved**, the enigmatic young woman, mysteriously appears from a body of water. She is widely believed to be the ghost of Sethe’s murdered baby, and Morrison herself confirmed this interpretation. Her name is derived from the single word Sethe could afford to engrave on the tombstone. Beloved serves as a catalyst, unearthing repressed trauma but also consuming Sethe’s life.

Read more about: Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’: A Profound Examination of Slavery’s Enduring Scars and the Pursuit of Self

**Paul D**, who retains his name from enslavement, carries the deep psychological scars of Sweet Home and the chain gang within his metaphorical “tobacco tin” heart, which Beloved unsettlingly opens. He seeks a romantic relationship with Sethe, acts fatherly towards Denver, and is the first to suspect Beloved’s true nature, yet struggles to fully comprehend Sethe’s profound motherhood. **Denver**, Sethe’s remaining child at 124, transforms from a childish, isolated figure into a protective woman, eventually fighting for her own independence and her mother’s wellbeing, breaking the cycle of isolation. **Baby Suggs**, Sethe’s mother-in-law, bought her freedom by her son Halle, becoming a revered community leader in Cincinnati who preached self-love to Black people. Her legacy is complicated by the community’s envy and Sethe’s actions, leading her to retreat to her bed before her death at 70. **Halle**, Baby Suggs’s son and Sethe’s husband, is only seen in flashbacks, presumed to have gone mad after witnessing the violation of Sethe at Sweet Home. **Schoolteacher** embodies the brutal cruelty of slavery, viewing the enslaved as animals, and is the primary discipliner at Sweet Home. Finally, **Amy Denver**, a young white girl, provides crucial aid to a desperately pregnant Sethe during her escape, even helping deliver Denver, whose name honors her rescuer.

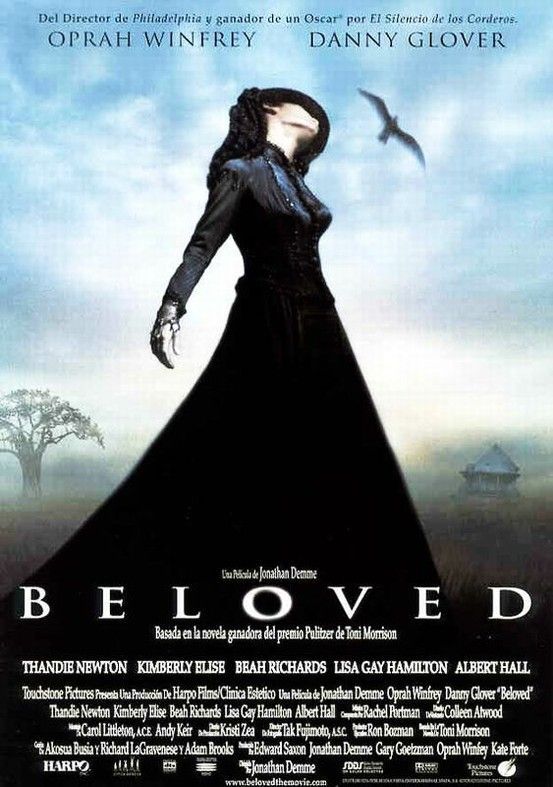

The novel’s powerful narrative has naturally extended beyond the written page, finding life in other forms. In 1998, *Beloved* was adapted into a major film directed by Jonathan Demme, notably produced by and starring Oprah Winfrey. Years later, in January 2016, BBC Radio 4 broadcast the novel in a 10-episode series as part of its “15 Minute Drama” program, adapted by Patricia Cumper.

The legacy of *Beloved* is multifaceted and enduring. It received the Frederic G. Melcher Book Award, an honor that prompted Toni Morrison to deliver a poignant acceptance speech on October 12, 1988. In her remarks, Morrison lamented the absence of a suitable memorial for the millions of human beings forced into slavery and brought to the United States. “There’s no small bench by the road,” she stated, emphasizing, “And because such a place doesn’t exist (that I know of), the book had to.” Inspired by her powerful words, the Toni Morrison Society initiated the “bench by the road” project, installing memorial benches at significant sites in the history of slavery in America. The very first ‘bench by the road’ was dedicated on July 26, 2008, on Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina, a poignant entry point for approximately 40% of enslaved Africans brought to the United States, an event that deeply moved Morrison. By 2017, the 21st bench was placed at the Library of Congress, dedicated to Daniel Alexander Payne Murray, the first African-American assistant librarian of Congress.

In addition to the Melcher Award, *Beloved* received the seventh annual Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights Book Award in 1988, an accolade given to novelists whose work faithfully reflects Robert Kennedy’s concerns for the poor and powerless, his struggle for justice, and his conviction that society must ensure a fair chance for all young people.

Read more about: Unlocking Life’s Profound Truths: 14 Essential Lessons People Learn Too Late, But You Don’t Have To

The critical reception of *Beloved* in 1987 marked a new height of acclaim for Morrison. Despite being nominated for the National Book Award, its failure to win sparked a significant protest. Forty-eight prominent African-American writers and critics, including luminaries such as Maya Angelou, Amiri Baraka, and Angela Davis, signed a letter of protest that was published in The New York Times Book Review on January 24, 1988, underscoring the novel’s profound importance within the Black literary community and beyond. The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, awarded later that year, along with other significant honors, affirmed its extraordinary literary merit.

Commentators have universally described *Beloved* as a profound exploration of complex notions: family, trauma, the repression of memory, and the vital act of restoring the historical record. It is widely seen as an attempt to give voice to the collective memory of African Americans. Critics and Morrison herself have pointed out that the controversial epigraph, “60 million and more,” stems from studies on the African slave trade, estimating the horrific loss of life in transit. A notable academic debate has revolved around the nature of the character Beloved herself—whether she is a literal ghost or a real person. Elizabeth B. House, for instance, argues for a nuanced interpretation of two probable instances of mistaken identity, where Beloved, haunted by the loss of her African parents, comes to believe Sethe is her mother, and Sethe, longing for her dead daughter, is easily convinced Beloved is her lost child. This interpretation, House contends, clarifies many puzzling aspects and underscores Morrison’s focus on familial ties.

Morrison’s work, particularly *Beloved*, has been lauded for its capacity to act as a means of healing and recovery. The concept of “rememory,” as Sethe terms it, is a critical lens through which to view the process of confronting and transforming past horrors. While some critics argue for the curative power of Morrison’s narratives, others, like Jill Matus, note that her representations of trauma are “never simply curative,” potentially provoking readers to vicarious experience and acting as a “means of transmission.” The critical discourse surrounding *Beloved* has evolved, as exemplified by Ann Snitow’s initial mixed reaction and subsequent change of position after deeper engagement with scholarly interpretations, revealing the ideological complexities in defining and evaluating American and African-American literature.

Read more about: Toni Morrison’s Beloved: A Haunting Legacy of Memory, Motherhood, and Resistance

In November 2019, the BBC News notably included *Beloved* on its list of the 100 most inspiring novels, affirming its lasting global impact and inspirational power. Yet, despite its accolades and profound literary significance, *Beloved* has been a frequent target of controversy and censorship in U.S. schools, particularly in recent years. Common reasons cited for attempts at banning include explicit content related to “bestiality, infanticide, sex, and violence.”

One prominent instance occurred in 2007 when the novel was abruptly removed from an AP English class at Eastern High School in Louisville, Kentucky, upon the order of the school’s principal. A parent’s complaint about language on page 13 led to the ban just as the class was nearing completion of the book. However, thanks to the concerted efforts of the English teacher, like-minded colleagues, and an outpouring of support from Eastern’s alumni, the ban was swiftly lifted, and *Beloved* continues to be taught at the high school, a testament to the importance of literary freedom and academic integrity.

More recently, in Virginia, *Beloved* faced attempts at removal from the Fairfax County senior English reading list in 2017 following a parent’s complaint that the book included “scenes of violent sex, including a gang rape, and was too graphic and extreme for teenagers.” This parental concern escalated, inspiring the creation of the “Beloved Bill,” proposed legislation that would have mandated Virginia public schools to notify parents of any “sexually explicit content” and provide alternative assignments if requested. Governor Terry McAuliffe ultimately vetoed this bill.

Read more about: You Won’t Believe These 13 Celebrities Are Working Regular Jobs Now

However, the controversy surrounding *Beloved* resurfaced dramatically during McAuliffe’s 2021 gubernatorial campaign. His statement during a debate, “Yeah, I stopped the bill that—I don’t think parents should be telling schools what they should teach,” was seized upon by his opponent, Glenn Youngkin. Youngkin subsequently produced a television commercial featuring a parent recounting her efforts to have the book banned, highlighting the persistent tension between parental rights and educational autonomy, even without explicitly naming the book, its author, or subject. These incidents underscore *Beloved*’s enduring power to provoke necessary, if at times uncomfortable, discussions about history, trauma, and freedom of expression within the American educational system.

Read more about: Adapting to Change: 10 Everyday Items and Practices on the Verge of Being Banned

Toni Morrison’s *Beloved* stands as a monumental literary achievement, a work that not only illuminates the darkest corners of American history but also explores the profound psychological and emotional scars of slavery with unparalleled empathy and narrative strength. It is a testament to the resilience of the human spirit, the enduring power of family bonds, however fractured, and the arduous journey towards healing and self-acceptance. The novel compels us to remember the sixty million and more, to confront the uncomfortable truths of the past, and to recognize the heroism in those who fought, survived, and sought to love in the face of unimaginable adversity. Its enduring presence in our literary landscape ensures that the echoes of 124 Bluestone Road will continue to resonate, challenging, inspiring, and reminding us of what it means to be truly human.