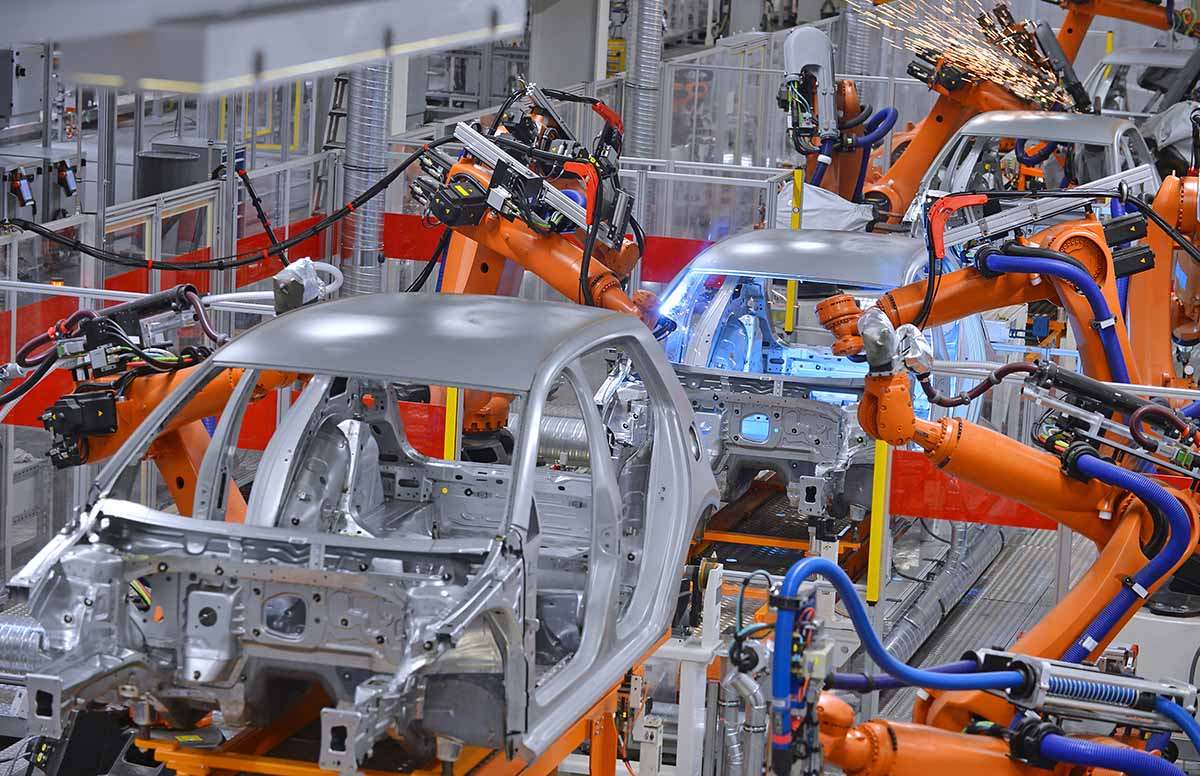

The intricate web of supplier-dealer relationships is a cornerstone of the automotive world, much like any industry relying on a robust supply chain for replacement parts and equipment. From the smallest independent repair shop to the largest dealership network, access to genuine components and critical information is paramount for maintaining the vehicles and machinery that drive our daily lives and commerce. But what happens when a manufacturer, a key supplier in this ecosystem, decides to flat-out deny selling parts to a particular entity, perhaps even a competitor?

This isn’t merely a business decision; it plunges into the complex legal territory of federal antitrust laws, particularly concerning a concept known as “refusal to deal.” While at first glance it might seem counterintuitive to allow a supplier to dictate who gets access to their products, there are deeply rooted legal principles that grant manufacturers significant latitude in choosing their business partners. Understanding these principles is not just for legal experts; it’s essential for anyone navigating the competitive landscapes of automotive, HVAC, and countless other sectors.

In this in-depth exploration, we’re going to pull back the curtain on the fundamental legal underpinnings that govern these crucial decisions. We’ll dive into the historic rulings and current interpretations that shape a supplier’s right to refuse sales, and equally important, the specific circumstances under which such a refusal could be deemed illegal. Buckle up as we dissect the foundational rights and critical limitations that define the very boundaries of trade freedom in the supply chain.

1. **The Fundamental Right to Choose Business Partners: The Bedrock Principle**At the very heart of federal antitrust law lies a principle that has stood for over 85 years: a seller generally possesses the inherent right to choose its business partners. This isn’t a minor footnote but a fundamental tenet, asserting that a firm’s refusal to deal with any other person or company is entirely lawful under most circumstances. It’s about preserving the autonomy of individual businesses in a free market.

This long-recognized right is not without its historical weight, having been articulated by the U.S. Supreme Court decades ago. The Court affirmed that businesses engaged in private commerce have the freedom to “exercise his own independent discretion as to parties with whom he will deal.” This statement underscores a core American economic philosophy, emphasizing individual business liberty in trade relationships.

Therefore, when a manufacturer or supplier decides not to sell parts to a particular dealer or competitor, this action starts from a position of legality. It represents an independent business decision, free from external coercion or collaboration. This right forms the very bedrock upon which all subsequent discussions about “refusal to deal” are built, making it the essential starting point for any analysis of supplier behavior.

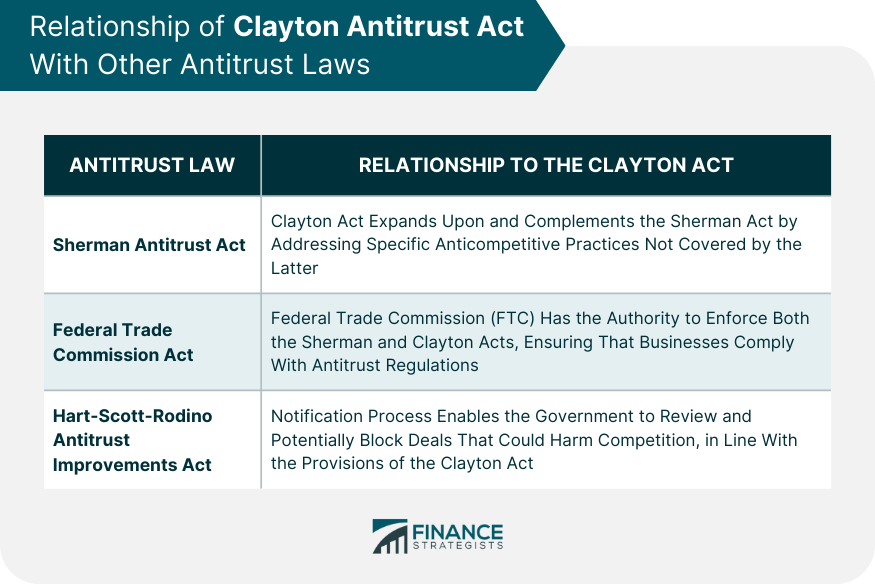

2. **The Sherman Act’s Mandate: Preserving “Freedom of Trade”**The purpose of these established legal frameworks, specifically the Sherman Act, is not to stifle business discretion but rather to “preserve the right of freedom of trade.” This pivotal legislation aims to ensure that trade remains open and competitive, but it also recognizes the legitimate space for individual firms to make their own choices regarding their commercial interactions. The Act draws a crucial line.

The Sherman Act explicitly states that it “does not restrict the long recognized right of a trader or manufacturer engaged in an entirely private business, freely to exercise his own independent discretion as to parties with whom he will deal.” This powerful articulation clarifies that the law intervenes only when that discretion is abused or becomes part of a larger, illegal scheme. It distinguishes between independent decision-making and anti-competitive conduct.

This remains a fundamental rule of federal antitrust law, providing a clear boundary. On one side, we have legal, independent decision-making by businesses, allowing them to operate efficiently and strategically. On the other side, we find illegal joint or monopolistic activity, which the Act is specifically designed to prevent, ensuring that no single entity or group of entities can unfairly dominate a market by stifling competition through nefarious means.

3. **Minimum Resale Price Policies: Manufacturer’s Discretion in Pricing and Termination**A common scenario that highlights a manufacturer’s discretion involves minimum resale price policies. Imagine owning a small clothing store, similar to the hypothetical case presented in legal discussions, where the manufacturer of a popular line cuts you off. The reason given is often a manufacturer’s policy that its products “should not be sold below the suggested retail price,” and that “dealers that do not comply are subject to termination.”

Legally, a manufacturer is generally allowed to implement and enforce such a policy. The law supports a manufacturer’s right to insist that its dealers sell a product above a certain minimum price. Furthermore, they can legally terminate a dealer who fails to honor this established policy, acting within their rights to manage their brand and distribution channels as they see fit. This provides a framework for consistent market positioning.

Manufacturers adopt these policies for legitimate business reasons that are recognized by law. One primary motivation is to encourage dealers to “provide full customer service,” ensuring a certain quality of sales experience. It also serves to prevent “free riding,” where some dealers might undercut prices by offering minimal service, while others invest heavily in customer support, only to lose sales to the discounters. This protection helps maintain a level playing field for dealers committed to full service.

4. **Illegal Agreements: When Refusal Crosses the Line into Anticompetitive Conspiracy**While manufacturers generally have broad rights to refuse to deal, there are critical limitations, particularly concerning collaboration with competitors. The legal landscape shifts dramatically if a refusal to sell parts or products is “the product of an anticompetitive agreement with other firms.” This distinction is paramount, as independent action is legal, but coordinated action to harm competition is not.

The hypothetical clothing store scenario provides a clear illustration: if the manufacturer dropped the store “because my competitors complained that I sell below the suggested retail price,” and it was due to an “agreement with your competitors to cut you off to help maintain a price they agreed to,” then the manufacturer’s action could be illegal. The key is the existence of an agreement or conspiracy between the manufacturer and the competitors.

This “conspiracy” element is what transforms a legitimate refusal to deal into an antitrust violation. It signifies a coordinated effort among market players to control prices or exclude competition, rather than an independent business decision. Federal antitrust laws are specifically designed to dismantle such arrangements, ensuring that competition, not collusion, dictates market dynamics and benefits consumers.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/natural_monopoly.asp-FINAL-6752adca612b4c648c1447518584dcd7.png)

5. **Monopoly Acquisition or Maintenance: Refusal as a Predatory Strategy**Another significant limitation on a manufacturer’s right to refuse to deal arises when that refusal is part of a “predatory or exclusionary strategy to acquire or maintain a monopoly.” This delves into the realm of monopolization, where a dominant firm uses its power to squash competition, not through superior products or services, but through unfair or coercive practices. The law is vigilant against such tactics.

The overarching goal of antitrust laws is to prevent a business from achieving or solidifying a monopoly through illegitimate means. Therefore, if a manufacturer’s refusal to do business with dealers is specifically intended “to achieve or maintain a monopoly,” that action would be illegal. It shifts from being a strategic business choice to an abusive exercise of market power that harms the competitive environment.

This restriction ensures that even powerful manufacturers cannot weaponize their supply decisions to systematically eliminate rivals and dominate a market. The intent behind the refusal becomes a crucial factor in legal analysis. It’s not just about the act of refusing, but the strategic, anti-competitive purpose driving that refusal that attracts legal scrutiny and potential penalties under federal antitrust statutes.

6. **Manufacturer’s Monopoly over Its Own Products: A Crucial Distinction**A frequently misunderstood aspect of antitrust law involves a manufacturer’s control over its own proprietary products. Courts have often stated that a “manufacturer is entitled to maintain a monopoly over its own products.” This might sound contradictory to the principles of competition, but it’s a vital distinction that clarifies what is and isn’t considered an illegal monopoly under the law.

The critical caveat here is that this “monopoly over its own products” is legal “so long as the manufacturer does not thereby monopolize the entire market.” This means a company can exclusively control the production and sale of its brand-specific genuine parts, for example, without violating antitrust laws, provided that there are reasonable substitutes or a broader competitive market for the function those parts perform.

This legal allowance recognizes the proprietary nature of a manufacturer’s intellectual property and investment in design and production. It prevents competitors from simply demanding access to a company’s unique components, while still ensuring that the broader market for a particular good or service remains competitive. The focus is on the overall market for a product category, not just a single brand’s offerings.