The vocation of pastoring a church extends far beyond the familiar Sunday sermon, encompassing a profound blend of spiritual leadership, intricate administration, and deeply personal mentorship. It is a demanding role that requires not only dedication and wisdom but, at its very core, a true servant’s heart. Despite its centrality to many communities, the precise nature of a pastor’s work remains a question that even adults may find challenging to articulate fully.

Indeed, the question “What does a pastor do?” might not be so easily answered, a reality brought into sharp and humorous focus by a kindergarten-aged son’s biographical sketch. When asked about his father’s occupation, the expected responses—perhaps “He’s a minister of the church,” or “He preaches God’s Word,” or even “He tells people about Jesus”—were notably absent. Instead, much to his father’s chagrin, the simple and candid reply was, “He works on his computer and drinks coffee.” This anecdote, while lighthearted, underscores a common lack of detailed understanding regarding the full scope of a pastor’s responsibilities, a gap that this exploration aims to bridge.

At the very foundation of a pastor’s ministry lies a distinct calling, one that sets it apart from the general call to salvation shared by all believers. The Apostle Paul, in his communication with young Timothy, emphasized this unique summons through “the laying on of hands,” describing it unequivocally as a “holy calling,” as detailed in 2 Timothy 1:6–9. This holy calling signifies that the minister is specifically set apart by and through the church, being tasked with representing the Lord Jesus Christ through both word and deed.

In this capacity, the pastor serves as Christ’s ambassador, being entrusted with the authoritative keys of the kingdom, a concept articulated in 2 Corinthians 5:20 and Matthew 16:19. Crucially, this representational authority is never to be exercised for self-promotion, as admonished in 2 Corinthians 4:5, nor is it to be employed to dominate those under one’s spiritual care, a principle reinforced in 1 Peter 5:3. Instead, the pastoral office is characterized by humble service, a model perfectly exemplified by our Lord Himself when He washed His disciples’ feet, as recorded in John 13:1 – 17. Those who embrace this calling and purpose with such servant leadership are honored by the Lord and, correspondingly, are to be honored by the congregation they shepherd, as instructed in 1 Timothy 5:17.

From this profound and holy calling arise three primary responsibilities that define the essence of a pastor’s work: to lead, to provide, and to protect. These duties encapsulate the dynamic and demanding nature of shepherding a congregation, guiding them along their spiritual journey.

First and foremost, a pastor is called to lead the church of the Lord Jesus Christ. However, this leadership must not be conflated with the metrics of corporate America, where success is often quantitatively measured by bottom-line results. Leadership within Christ’s church is, above all, leadership demonstrated through example—an unwavering example of godliness and Christlikeness that inspires and guides the flock.

When Joshua was tasked with leading the people of God into the promised land, the Lord did not provide him with detailed military strategies as the sole key to victory. Instead, the divine instruction focused on spiritual discipline: “This Book of the Law shall not depart from your mouth, but you shall meditate on it day and night, so that you may be careful to do according to all that is written in it. For then you will make your way prosperous, and then you will have good success,” as recounted in Joshua 1:8. This ancient mandate highlights the spiritual bedrock of true leadership.

Similarly, when addressing the church in Corinth, a community grappling with rampant division and moral confusion, the Apostle Paul did not issue a list of rules but rather pointed to his own life as a tangible guide to godliness. His exhortation was direct and personal: “Be imitators of me, as I am of Christ,” found in 1 Corinthians 11:1. It is from this unbreakable foundation of personal integrity and godly example that a minister derives the authority and capacity to effectively lead the people of God, both in their worship of the divine and in the manifold ministries of the church.

Second, a pastor is called to provide for the church of the Lord Jesus Christ. This provision manifests primarily through the ministry of the Word, the sacraments, and prayer. These are described as the “special—yet ordinary—means of grace that God has appointed to fully and sufficiently minister to His people, communicating to them the benefits of their redemption in Christ.” The minister’s central task is to faithfully and consistently administer these essential means to the flock entrusted to his care.

It is imperative that a pastor remains undistracted by other concerns, no matter how valid they may seem. The Apostle Peter underscored this crucial prioritization in Acts 6, when the early church faced pressing needs concerning the daily distribution of food. Peter’s response clarified the hierarchy of ministerial duties: “It is not right that we should give up preaching the word of God to serve tables… But we will devote ourselves to prayer and to the ministry of the word,” as stated in Acts 6:2 and 6:4. This emphasis does not diminish the importance of other ministries within the church; rather, it correctly subordinates them under the foundational provision of spiritual nourishment, a lesson Peter learned directly from the Lord’s repeated commission to “feed my sheep,” as recorded in John 21:17.

Third, a pastor is tasked with the solemn duty to protect the church of the Lord Jesus Christ. This responsibility traces its origins all the way back to Adam, the first man, who was placed in the Garden of Eden “to work it and keep it,” as described in Genesis 2:15. Adam was assigned to cultivate the garden’s flourishing and to guard it from any elements that might hinder its vitality. Tragically, Adam failed in this vital protective role, succumbing to the serpent’s deception through his wife, Eve, thereby plunging all of humanity into the abyss of sin.

To this day, the insidious forces of sin and Satan relentlessly plague the world, and they target the church with particular intensity. Consequently, the minister must remain ever vigilant in guarding the flock. He is specifically called to issue warnings against spiritual dangers and to engage in spiritual warfare against the attacks of the evil one, as powerfully articulated in Ephesians 6:10 – 20. In fulfilling this duty, the pastor continually proclaims the ultimate victory that has already been secured by the resurrected and ascended Lord Jesus Christ. Even amidst the ongoing struggle with the fallenness of the world and the inherent flaws of human hearts, the church stands eternally victorious in Him.

Furthermore, the pastor must labor diligently to uphold both the peace and purity of the church community. The Apostle Paul delivered a solemn charge to the elders of Ephesus, emphasizing this guardianship: “Pay careful attention to yourselves and to all the flock, in which the Holy Spirit has made you overseers, to care for the church of God, which he obtained with his own blood. I know that after my departure fierce wolves will come in among you, not sparing the flock… Therefore, be alert,” as recorded in Acts 20:28 – 31. These three overarching responsibilities—to lead, provide, and protect—are beautifully encapsulated by the most frequent biblical analogy for leaders of God’s people: the shepherd. The very title “pastor” is derived from this profound image of tending, feeding, and nurturing Christ’s beloved flock. This shepherding model finds its perfect example, its ceaseless strength, and its eternal security in the Chief Shepherd, the Lord Jesus Christ, “who lays down his life for the sheep,” as articulated in John 10:11. For this foundational reason, the Apostle Peter offers an enduring charge to all ministers of the gospel: “Shepherd the flock of God that is among you, exercising oversight… willingly… eagerly… being examples to the flock. And when the chief Shepherd appears, you will receive the unfading crown of glory,” as found in 1 Peter 5:2 – 4.

Beyond these foundational, divinely ordained responsibilities, the daily life of a pastor involves a multifaceted array of duties crucial for the holistic functioning of a church and the spiritual well – being of its members. At the very core is the task of “Preaching and Teaching the Word of God.” This involves the accurate interpretation of Scripture, the provision of sound doctrine, and the application of biblical principles to the congregation’s lives, demanding extensive sermon preparation, diligent Bible study, and clear communication.

Central to the pastoral identity is “Shepherding the Congregation.” This means actively caring for the spiritual welfare of the flock by offering guidance, counseling, and encouragement throughout their faith journey. It crucially involves being consistently available for prayer, conducting visitations, and providing comprehensive spiritual support to individuals in their times of need. A pastor is also charged with “Leading by Example,” which necessitates living a life that authentically mirrors Christ’s teachings, embodying humility, integrity, and godliness in every facet of existence, thereby serving as an indispensable role model for the entire congregation.

The administrative demands of the role are substantial, falling under “Administering Church Operations.” This includes the practical management of church staff, the meticulous organization of various church events, the prudent oversight of financial matters, and ensuring the seamless and efficient functioning of the church as an institution. Effective leadership in this domain requires well – honed organizational skills coupled with a clear and compelling vision for the church’s ongoing growth and development. Additionally, pastors are called to provide “Pastoral Care,” offering profound comfort and compassionate counseling during times of crisis. This critical duty spans grief counseling, marital support, and assisting members in navigating exceptionally difficult circumstances, requiring pastors to be empathetic listeners who consistently offer biblical wisdom and encouragement.

Read more about: California: A Comprehensive Look at the Golden State’s Enduring Legacy, Dynamic Landscape, and Global Influence

The Bible employs several terms interchangeably with “pastor” to describe the spiritual leaders of a church, each term illuminating a different facet of their comprehensive role. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines a pastor as “a spiritual overseer,” a role deeply embedded in biblical texts. The very word “pastor” originates from the Latin term pastoris, meaning “keeper of cattle” or “shepherd,” vividly illustrating the pastoral responsibility to tend to a flock.

In John 10:11, Jesus Himself declares, “I am the good shepherd,” establishing the ultimate exemplar for those who lead the church. Church leaders, with Christ as their head and role model, similarly endeavor to “shepherd” their own flock—their congregation. This concept of “keeper” or “shepherd” serves as a powerful metaphor for the profound spiritual care and diligent tending that a church leader provides to a church body. Beyond “pastor,” the Bible frequently uses terms such as “elder,” “overseer,” and “deacon” to delineate roles and specific responsibilities within the church hierarchy.

For instance, in 1 Timothy 3:1, the Apostle Paul articulates the noble aspiration: “Whoever aspires to be an overseer desires a noble task.” The original Greek term for overseer, episkopos, refers broadly to a visitation or the coming of divine power, and more specifically to an overseer or bishop within a church, signifying an office of significant responsibility and leadership. This same word, episkopos, is found in Acts 20:28, where Paul imparts guidance to the leaders of the church in Ephesus: “Keep watch over yourselves and all the flock of which the Holy Spirit has made you overseers. Be shepherds of the church of God, which he bought with his own blood.” Earlier in the same chapter, Paul also refers to these church leaders as “elders,” implying a synonymous relationship between the two terms.

The original Greek word for elder is presbyteros, which, according to the NIV Exhaustive Concordance Dictionary, can mean “an official leader of the Jewish community” or, in the epistles, an “older man” and “older woman,” who may or may not be official leaders of the church, depending on the context. The Apostle Peter, in 1 Peter 5, uses the term “elder” (presbyteros) to describe himself and offers profound wisdom to his fellow elders, explaining that they must be willing shepherds who conscientiously care for their flock of Jesus-followers.

Another significant term is “deacon,” derived from the original Greek word diakonos, meaning “servant or minister” in the church. In 1 Timothy 3:12, Paul specifies that deacons must embody the same fundamental values as overseers, requiring them to be faithful in marriage, to serve diligently, and to manage their children and household commendably. While “children” in the original Greek can refer to offspring as well as those spiritually nurtured in the faith, and “household” can denote a physical home or a temple, the overarching message remains clear: whether termed an elder, overseer, or deacon, the pastor’s paramount duty is to serve, to meticulously care for their congregation, and to consistently exemplify upright and godly behavior in all aspects of their life.

Indeed, a pastor is held to specific, demanding duties and requirements that elevate their standard of conduct. In 1 Timothy 3:2-7, Paul outlines these essential qualities for an “overseer”: they “must be above reproach, faithful to his wife, temperate, self-controlled, respectable, hospitable, able to teach, not given to drunkenness, not violent but gentle, not quarrelsome, not a lover of money.” Furthermore, a pastor “must manage his own family well and see that his children obey him, and he must do so in a manner worthy of full respect. (If anyone does not know how to manage his own family, how can he take care of God’s church?) He must not be a recent convert, or he may become conceited and fall under the same judgment as the devil. He must also have a good reputation with outsiders, so that he will not fall into disgrace and into the devil’s trap.”

Similarly, in 1 Peter 5:2-3, Peter instructs elders to be “shepherds of God’s flock that is under your care, watching over them—not because you must, but because you are willing, as God wants you to be; not pursuing dishonest gain, but eager to serve; not lording it over those entrusted to you, but being examples to the flock.” The Epistle to Titus further reinforces these qualifications, with Paul stating in Titus 1:6-9 that an elder must be “blameless, faithful to his wife, a man whose children believe and are not open to the charge of being wild and disobedient. Since an overseer manages God’s household, he must be blameless—not overbearing, not quick-tempered, not given to drunkenness, not violent, not pursuing dishonest gain. Rather, he must be hospitable, one who loves what is good, who is self-controlled, upright, holy and disciplined. He must hold firmly to the trustworthy message as it has been taught, so that he can encourage others by sound doctrine and refute those who oppose it.”

In essence, the pastor must embody integrity, be worthy of respect, possess profound self-control, abstain from drunkenness, be genuinely welcoming and hospitable, maintain a gentle demeanor, avoid quick temper, be a good spouse and parent whose family life reflects their faith, believe and be capable of teaching the gospel, be free from the love of money, not be a recent convert, and fundamentally operate as a servant-leader. The implication is clear: pastors are indeed held to a higher standard. As James 3:1 warns, “Not many of you should become teachers, my fellow believers, because you know that we who teach will be judged more strictly.” Titus 1:7 further emphasizes this, stating, “Since an overseer manages God’s household, he must be blameless.” While all individuals are called to repentance and faith, those entrusted with leading others bear a unique and special responsibility, not only to teach but also to serve as living, human examples for others to emulate.

The distinction between a priest and a pastor, while often conflated by the public, represents a significant divergence in denominational theology and church leadership. While both serve as “shepherds of the flock,” caring for the spiritual needs of their congregants, they do so within fundamentally different frameworks. A key theological difference lies in the concept of absolution. A priest, typically found in Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Anglican, and Episcopal churches, hears confessions of sin and may declare, “I absolve you from your sins.” This act, where “absolve” means to “free from a charge of wrongdoing,” essentially implies the priest’s ability to pardon sins. In contrast, while a person may confess sins to a pastor—an encouraged practice given the biblical admonition to confess sins to one another for healing (James 5:16)—a pastor would not grant absolution.

A pastor emphasizes that only God can pardon sin, encouraging the individual to confess directly to God and receive divine forgiveness. While a pastor might assist in prayer for forgiveness or encourage asking forgiveness from those wronged, they do not hold the authority to absolve sins themselves. A pastor is specifically defined as the “spiritual leader of a Protestant church.” Protestant churches, including mainline denominations like Presbyterian, Methodist, and Baptist, as well as most non-denominational and Pentecostal churches, adhere to core beliefs such as every believer having direct access to God through Jesus Christ, the Bible as the final authority on doctrine, and salvation by faith alone. The term “pastor” itself derives from the root of “pasture,” metaphorically casting the pastor as a “shepherd of people, helping them get on and stay on the right spiritual path, guiding them, and feeding them with God’s Word.”

The historical origins of these roles further illuminate their differences. In the Old Testament, a priest was a man divinely called to represent people in matters pertaining to God, offering gifts and sacrifices for sin, as noted in Hebrews 5:1-4. The Aaronic priesthood, established nearly 3,500 years ago, set apart Moses’ brother Aaron and his descendants to offer sacrifices, serve the Lord, and pronounce blessings. With Jesus’ death on the cross as the ultimate sacrifice, the need for animal sacrifices ceased, though this was not immediately understood by the Jewish priests. The Jewish priesthood eventually ended in AD 70 with the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple.

Meanwhile, the early church, as documented in the New Testament, witnessed the emergence of various church leaders. The primary office encompassed positions interchangeably called elders (presbyterous), overseers/bishops (episkopon), or pastors (poimenas). Their core tasks included teaching, praying, leading, shepherding, and equipping the local church. Peter himself referred to his role as an elder and urged fellow elders to shepherd God’s flock (1 Peter 5:1-2). Paul and Barnabas appointed elders in each church during their missionary journeys (Acts 14:23), and Paul instructed Titus to do the same in every town (Titus 1:5). According to Paul, an overseer was a “steward or manager of God’s household” (Titus 1:7) and a “shepherd of the church” (Acts 20:28), with the word “pastor” literally meaning shepherd.

Another early church office was the deacon (diakonoi), or servant, as mentioned in Romans 16:1, Ephesians 6:21, Philippians 1:1, Colossians 1:7, and 1 Timothy 3:8-13. These individuals primarily addressed the physical needs of the congregation, such as ensuring widows received food (Acts 6:1-6), thereby freeing elders to focus on spiritual needs like teaching and prayer. However, certain deacons, like Stephen and Philip, also demonstrated remarkable spiritual ministries, performing miracles and powerfully witnessing for Christ (Acts 6:8-10; 8:4-8).

The emergence of Christian priests, as distinct from these early church roles, began in the mid-second century. Church leaders, such as Cyprian, the bishop/overseer of Carthage, started referring to overseers as priests primarily because they presided over the Eucharist (communion), which came to be seen as representing Christ’s sacrifice. This gradually led to the metamorphosis of pastors/elders/overseers into a priesthood role. While distinct from the Old Testament priesthood (it was not hereditary, nor did it involve animal sacrifices), by the late fourth century, as Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire, church worship became increasingly elaborate and ceremonial. Figures like Chrysostom began teaching the doctrine of transubstantiation, where the priest was believed to call down the Holy Spirit to transform the bread and wine into the literal body and blood of Christ. This development fostered a pronounced divide between the priests and ordinary congregants, as priests declared absolution of sins, effectively acting “in the person of Christ.”

Read more about: The Enduring Essence: How the Complexities of Womanhood Have Shaped Our World, Redefining Community and Connection

The Protestant Reformation in the 16th century marked a pivotal shift, rejecting the doctrine of transubstantiation and instead championing the “priesthood of all believers,” asserting that all Christians have direct access to God through Jesus Christ. Consequently, the role of a mediating priest was no longer part of Protestant churches, and their leaders reverted to being called pastors or ministers.

The responsibilities of pastors in Protestant churches are extensive, encompassing preparing and delivering sermons, leading church services, visiting and praying for the sick, performing baptisms, weddings, and funerals, and providing counseling—ranging from pre-marital and marital guidance to grief support and assistance with sin. They are also actively involved in evangelism and community outreach, aiming to bring new individuals into the church and disciple them in the faith. Administratively, pastors oversee church operations and finances, often serving on church boards and various committees. Priests in the Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Anglican, and Episcopal churches share many of these responsibilities, yet with notable distinctions. Catholic priests, for instance, pray the Liturgy of the Hours daily and celebrate Mass at least once a day, adhering to the belief in transubstantiation. Crucially, Catholic and Orthodox priests hear confessions and grant absolution.

The training and educational pathways for pastors and priests also vary considerably. For Protestant pastors, requirements fluctuate widely across denominations and individual churches. Some mandate a seminary education, typically lasting three to five years, while others accept graduates from Bible colleges. Some churches offer mentor-led training programs, involving extensive reading and theological papers, which may include online, night, or weekend classes—a particularly common approach on the mission field where funding and access to formal training may be limited. Post-education, or sometimes concurrently, pastoral candidates often spend at least a year serving as a Youth Pastor or Assistant Pastor under a Senior Pastor, gaining invaluable practical experience and mentorship.

For priests, particularly in Catholic, Orthodox, and Anglican traditions, a bachelor’s degree is generally a prerequisite, followed by a three- to five-year seminary education. During seminary, aspiring priests frequently shadow an experienced priest, observing their preaching, administration of sacraments, and ministry to the sick. In some dioceses, a committee rigorously evaluates candidates before seminary, making recommendations to the bishop regarding their suitability for ordination. A common trajectory involves being ordained as a deacon first, followed by ordination as a priest after approximately one year.

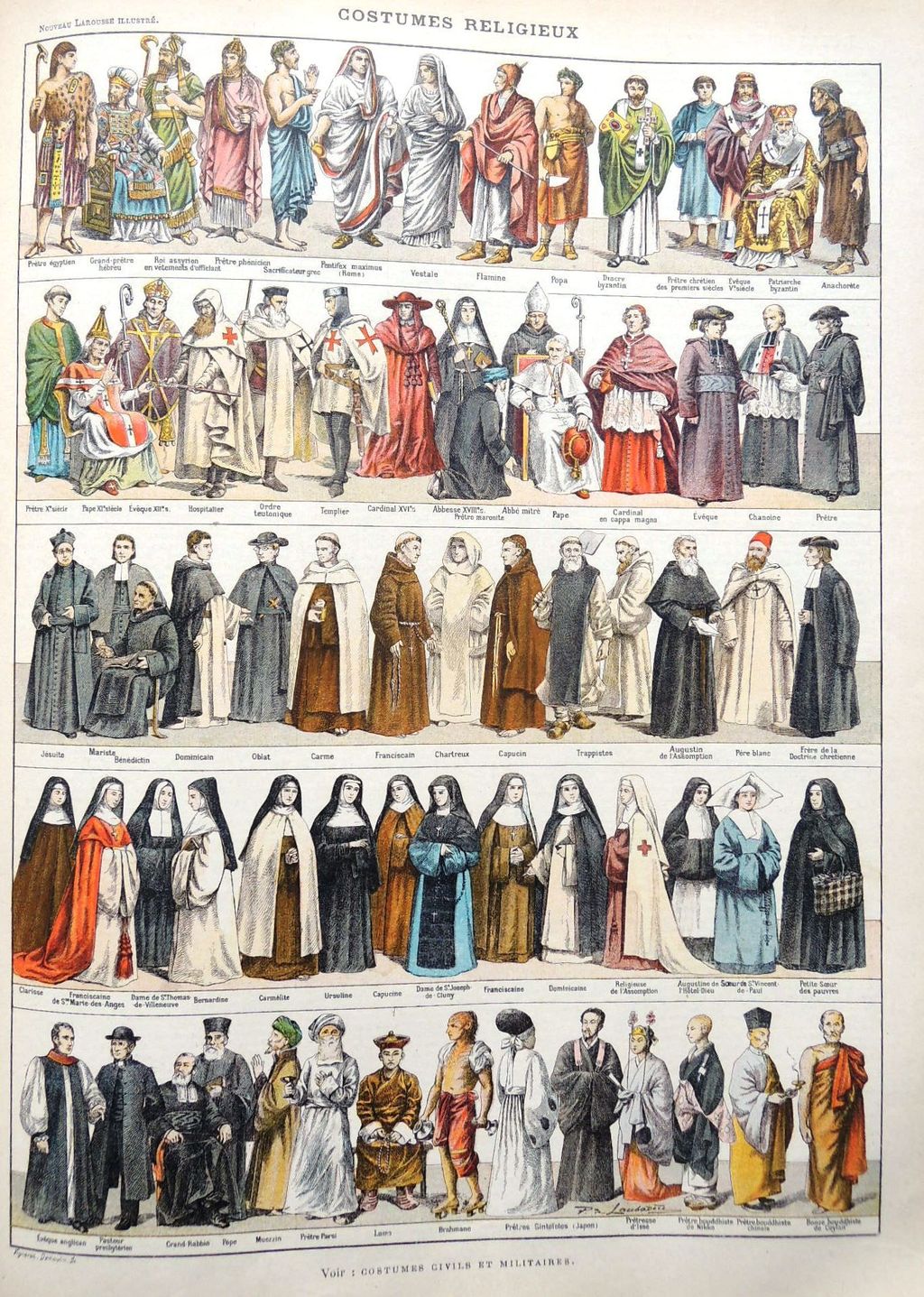

The attire of pastors and priests further underscores their denominational and theological differences. In many Reformed and Presbyterian churches, pastors traditionally wear a black “Geneva gown,” an ankle-length garment resembling an academic graduation robe. Many pastors in mainline denominations wear a stole, a long, typically brightly colored scarf. Methodist and Lutheran pastors commonly don a long black or white gown, topped with a white “surplice”—a shorter, wide-sleeved, thin robe—and a stole. Other Protestant pastors may opt for a suit or a dress shirt and tie for preaching. However, contemporary churches increasingly embrace informality, leading some pastors to wear jeans and casual shirts in the pulpit.

Conversely, priests adhere to a strict standard of vestments, each layer imbued with symbolic meaning. Their attire begins with an amice, a white linen rectangle covering the back from neck to waist, symbolizing defense against the devil. The alb, a white gown extending to the ankles, represents purity. A cincture, a cord tied around the waist, also signifies purity. They wear a stole, which embodies the priest’s authority and power, and over all this, the chasuble—a brightly colored cape. The colors of these robes, stoles, and chasubles are highly symbolic: green, worn on ordinary days, stands for hope; red, donned on Pentecost Sunday, represents the blood of Jesus and the fire of the Holy Spirit; yellow signifies glory, joy, and purity, worn at various times throughout the year; pink, worn on the third and fourth Sundays of Lent, symbolizes love and joy; and purple, worn during Advent, Lent, and Requiem Masses, represents repentance and humility.

Finally, the expectations regarding marriage and sexual intimacy present another stark contrast between pastors and priests. Protestant pastors can be either single or married, though many Protestant churches express a preference for hiring married pastors. This preference is partly rooted in biblical qualifications for an elder/overseer, which specify being “the husband of one wife” with believing and obedient children (Titus 1:6; 1 Timothy 3:2). Churches also often believe that married pastors are less susceptible to engaging in sexual sin and appreciate the support and participation of a pastor’s wife in various ministries. While marriage is not a strict requirement—the Apostle Paul, who wrote many of these qualifications, was himself single and expressed a wish that others might emulate him—the expectation is that if single, pastors are expected to be celibate. However, it is worth noting that in some very “progressive” denominations, pastors may live with partners outside of marriage, including same-sex partners.

Catholic priests, on the other hand, are strictly required to be single and non-sexually active, and they are not permitted to be part of the LGBTQ community. This celibacy requirement is a deeply ingrained tradition within the Catholic Church, shaping the very fabric of its priesthood.

From the ancient analogy of a shepherd tending his flock to the complex administrative tasks of a modern church, the pastor’s role is a profound and demanding calling. It requires singular dedication, a life lived as a testament to faith, and an unwavering commitment to leading, providing for, and protecting the spiritual welfare of the congregation. In a world often searching for moral clarity and spiritual sustenance, the faithful pastor stands as a beacon, guiding individuals through life’s complexities with the timeless wisdom of the divine. May God’s grace continue to raise up many more such devoted pastors, who will faithfully shepherd the church of the Lord Jesus Christ, embodying the love and sacrifice of the Chief Shepherd Himself, and inspiring their flocks toward unity in faith and maturity in Christ.

The tapestry of a pastor’s life is woven with threads of deep theological conviction, practical leadership, and compassionate care. They are entrusted with a sacred trust, tasked with cultivating not just individual souls but the collective spiritual health of entire communities. It is a role that demands constant learning, unwavering humility, and an enduring passion for God’s people. The ongoing vitality of the church depends on these dedicated individuals, whose labor is truly a joy when supported and understood. Thus, whether we call them “reverend,” “minister,” “preacher,” or “pastor,” it is crucial to recognize and honor the profound significance of their spiritual leadership, allowing their work to be a source of profound joy rather than an overwhelming burden.

Read more about: Beyond the Headlines: Discovering the Soul of Ukraine Through Its People, Traditions, and Resilient Spirit

Ultimately, the pastor stands as a pivotal figure in the spiritual landscape, a guide steadfastly committed to the foundational principles of Scripture and dedicated to the holistic well-being of the flock. Their profound impact extends far beyond the confines of weekly sermons, shaping lives and communities through diligent service and exemplary living. As the global Christian community continues to grow and evolve, the unwavering commitment of these spiritual leaders remains an indispensable cornerstone, fostering environments where faith can flourish and lives can be transformed. Their journey, often arduous yet always rewarding, mirrors the very essence of devoted service, echoing the divine commission to feed and care for the sheep. Through their steadfast efforts, the church continues its mission, building up the body of Christ until all attain unity in faith and the fullness of knowledge of the Son of God.