The concept of “woman” is far more intricate and dynamic than a simple definition might suggest. At its most fundamental, a woman is an adult female human, a biological reality rooted in genetics and anatomy, typically inheriting a pair of X chromosomes and possessing a female reproductive system that includes ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, vagina, and vulva.

Yet, the journey of defining womanhood stretches beyond mere biology, encompassing a rich tapestry of history, evolving societal roles, cultural expressions, and persistent challenges. From the etymological roots of the word itself to the complex interplay of hormones, health, and human rights, the narrative of women is one of continuous transformation and profound significance.

Tracing the linguistic lineage of “woman” reveals a fascinating evolution. In Old English, the term “mann” held a gender-neutral meaning akin to the modern “person.” The specific word for a female human was “wīf” or “wīfmann,” literally meaning ‘woman-person.’ It was only after the Norman Conquest that “man” began to denote ‘male human,’ and by the late 13th century, it had largely supplanted “wer,” the Old English term for ‘man.’

The consonants /f/ and /m/ in “wīfmann” eventually coalesced into our contemporary “woman,” while “wīf” narrowed its meaning to specifically denote a married woman, becoming “wife.” It is a common misconception, however, that “woman” is etymologically linked to “womb,” which in fact derives from the Old English “wamb,” meaning ‘belly’ or ‘uterus,’ with cognates in terms like the modern German colloquial “Wamme.

Beyond etymology, the terminology used to refer to women has also shifted over time. While “woman” can broadly mean any female human, it is often used specifically to distinguish an adult female from a girl. Historically, the word “girl” itself meant “young person of either sex” in English, only acquiring its specific female connotation around the early 16th century.

During the early 1970s, feminists notably challenged the colloquial use of “girl” to refer to fully grown women, recognizing its potential for offense. Consequently, terms like “office girl” have largely fallen out of common usage. Conversely, in certain cultures where female virginity is linked to family honor, the term “girl” (or its linguistic equivalent) persists as a descriptor for an unmarried woman, similar to the now largely obsolete English terms “maid” or “maiden.”

The social sciences have significantly broadened the understanding of what it means to be a woman since the early 20th century, particularly as women gained more rights and greater representation in the workforce. Scholarship in the 1970s marked a pivotal shift, moving towards a focus on the sex–gender distinction and the social construction of gender, acknowledging that womanhood extends beyond purely biological definitions.

Terms like “womanhood” simply refer to the state of being a woman, while “femininity” describes a set of typical female qualities often associated with certain attitudes toward gender roles. “Womanliness,” while similar to “femininity,” typically aligns with a different perspective on these roles. These distinctions underscore the nuanced understanding of identity beyond biological assignment.

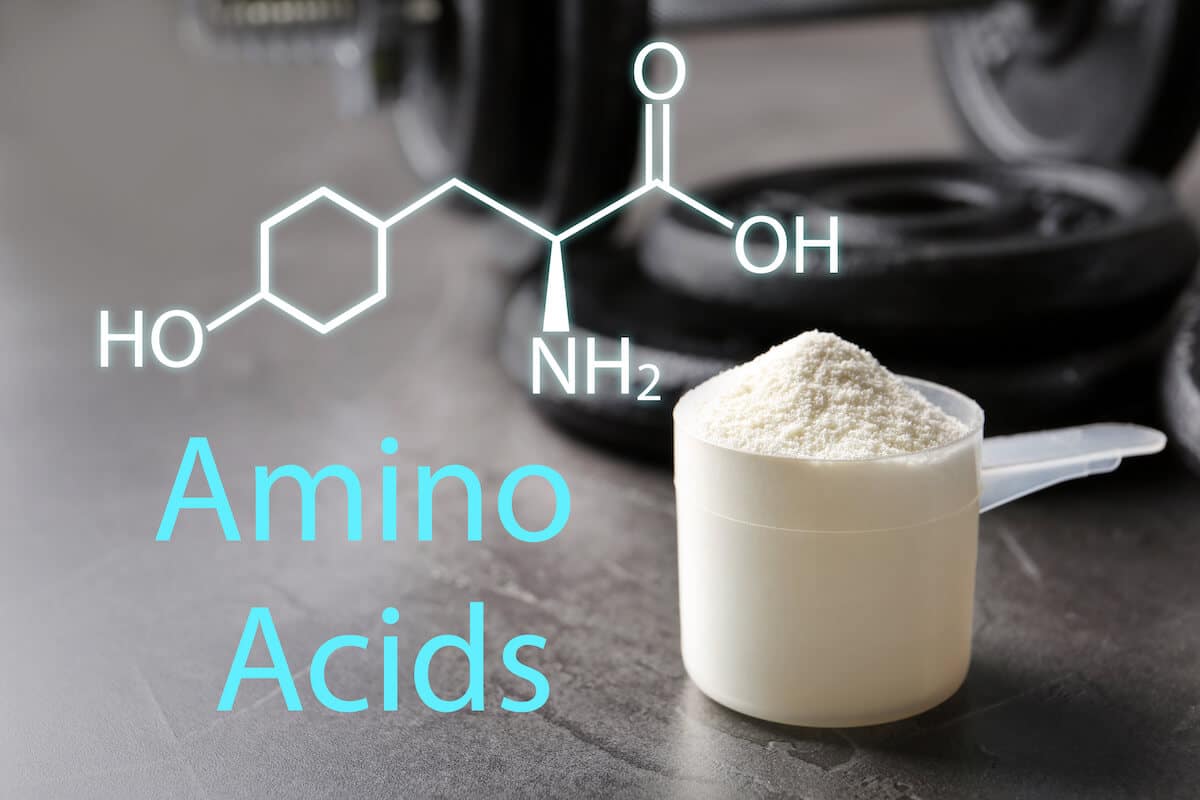

From a biological standpoint, the female body undergoes distinct changes from puberty through menopause. Puberty, triggered by pituitary gland signals, leads to ovarian hormone secretion, stimulating physical maturation including increased height and weight, body hair growth, breast development, and menarche—the onset of menstruation.

Most girls experience menarche between ages 12–13, becoming capable of pregnancy and childbirth. This process generally requires internal fertilization, although in vitro fertilization offers an external option. Humans, like other large mammals, typically give birth to a single offspring per pregnancy but are uniquely altricial, meaning their young are underdeveloped at birth and require extensive parental care.

Between ages 49 and 52, most women reach menopause, marking the permanent cessation of menstrual periods and the end of their childbearing years. Unlike many other mammals, humans often live many years beyond menopause, a phenomenon some biologists attribute to kin selection, with grandmothers playing a vital role in the care of grandchildren and other family members.

Physiologically, women’s bodies are adapted for reproduction and nurturing. The female reproductive system includes internal genitalia like the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, and vagina, and external genitalia known as the vulva. Mammary glands, a distinctive characteristic of mammals, produce milk for offspring, and their prominence in mature women is thought to be partly a result of sexual selection.

Estrogens, the primary female sex hormones, profoundly influence body shape, promoting the development of secondary sexual characteristics such as breasts and wider hips during puberty. This contrasts with testosterone, which can inhibit breast development and promote muscle and facial hair in pubescent females, highlighting the hormonal interplay in sex differences.

Beyond reproductive anatomy, women exhibit other physiological distinctions. They typically have lower hematocrit and hemoglobin levels than men, attributed to lower testosterone. Women’s hearts also display finer-grained muscle textures and differ in overall shape and surface area, and notably, age more slowly compared to men’s hearts, revealing subtle yet significant biological differences.

While girls are born slightly less frequently than boys, with a ratio of approximately 1:1.05, the global sex distribution saw 1018 men for every 1000 women in 2015. However, this general picture of womanhood is further enriched by recognizing the diversity within it.

Some women are intersex, meaning they are born with sex characteristics that do not align with typical notions of female biology, often with ambiguous genitalia. Most individuals with ambiguous genitalia are assigned female at birth, and most intersex women identify as cisgender, although the medical practices surrounding such assignments in youth can be controversial.

Similarly, some women are transgender, meaning they were assigned male at birth but have a female gender identity. Trans women may experience gender dysphoria, a distress stemming from the discrepancy between their gender identity and assigned sex. Gender-affirming care, including social and medical transition, such as feminizing hormone therapy or surgery, helps align their external presentation with their affirmed identity.

While most women are heterosexual and cisgender, female sexuality is highly variable, influenced by evolved predispositions, personality, upbringing, and culture. Significant minorities identify as lesbian or bisexual. The concept of femininity, encompassing attributes, behaviors, and roles typically associated with women and girls, is widely considered socially constructed yet also influenced by biological factors, and can be exhibited by both men and women.

Health considerations for women extend beyond reproduction, though these are often most evident. Sex differences in health are observed from the molecular to the behavioral scale, influenced by sex chromosomes, hormones, lifestyle, metabolism, and immune function. Women may also respond distinctly to drugs and have different thresholds for diagnostic parameters.

Certain diseases predominantly or exclusively affect women, including lupus, breast cancer, cervical cancer, and ovarian cancer. Gynaecology, the medical practice focused on female reproduction and reproductive organs, plays a crucial role in women’s health.

Maternal mortality, defined by the WHO as the death of a woman during pregnancy or within 42 days of termination, remains a critical global issue. In 2008, the WHO highlighted that over 500,000 women died annually from pregnancy and childbirth complications, urging midwife training and establishing programs like Action for Safe Motherhood.

In 2017, a staggering 94% of maternal deaths occurred in low and lower-middle-income countries, with sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia accounting for approximately 86%. Main causes include pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, unsafe abortion, and complications from malaria, HIV/AIDS, severe bleeding, and infections. While many European countries, Australia, Japan, and Singapore demonstrate high safety in childbirth, stark disparities persist globally.

Life expectancy generally favors women worldwide, who live six to eight years longer than men, an advantage that begins at birth. This difference is attributed to a combination of biological advantages and gendered behavioral differences, such as women being less likely to engage in unhealthy behaviors like smoking and reckless driving.

However, in some developed countries, this gap is narrowing, possibly due to increased rates of smoking among women and improved health among men. The World Health Organization cautions that “the extra years of life for women are not always lived in good health,” underscoring the ongoing need for comprehensive women’s health initiatives.

Reproductive rights, encompassing legal rights and freedoms related to reproduction and health, are fundamental human rights. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics emphasizes women’s right to control and decide freely on matters of their sexuality and reproductive health, free from coercion or discrimination.

Globally, 56 million induced abortions occurred annually between 2010 and 2014, with about 25 million deemed unsafe. Unsafe abortions lead to significant mortality, particularly in developing regions and sub-Saharan Africa, where restrictive laws, poor service availability, high costs, stigma, and other barriers contribute to these tragic outcomes.

In recent history, gender roles have undergone dramatic shifts. Traditionally, middle-class women were confined to domestic tasks and childcare, while economic necessity often compelled poorer women into lower-paying external employment. The shift from “dirty” factory jobs to “cleaner” office roles, demanding more education, further catalyzed changes in attitudes toward women in the workforce.

Married women’s participation in the U.S. labor force significantly rose from 5.6–6% in 1900 to 23.8% in 1923, contributing to a revolution where women became increasingly career and education oriented. Despite institutional efforts in the 1980s to equalize workplace conditions, women often remained primarily responsible for domestic labor and childcare, hindering their professional advancement.

Historical precedents include U.S. women’s colleges requiring female faculty to remain single, reflecting the societal belief that women could not manage both a career and family. As sociologist Harriet Zuckerman observed, “Being a scientist and a wife and a mother is a burden in society that expects women more often than men to put family ahead of career.” Such ingrained expectations continue to impact professional women.

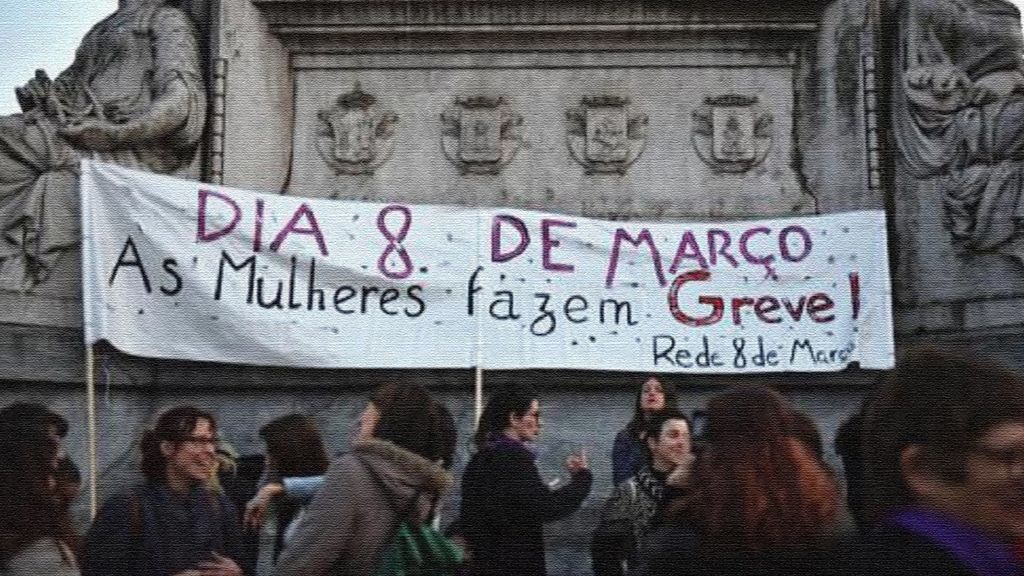

Despite advances fueled by economic changes and feminist movements advocating for equal opportunities, modern women in Western societies still encounter workplace challenges and issues related to education, violence, healthcare, politics, and motherhood. Sexism, though varying in form and severity, remains a pervasive barrier globally.

Violence against women, defined by the UN as “any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering to women,” is a deeply rooted problem. It manifests in the family, within communities, and can even be perpetrated or condoned by the state, reflecting historically unequal power relations.

Surveys by UNICEF reveal alarming social norms in some regions, with high percentages of women believing a husband is justified in hitting his wife. Specific forms of violence include female genital mutilation, sex trafficking, forced prostitution, forced marriage, rape, sexual harassment, honor killings, and acid throwing. Laws and their enforcement vary widely, with some countries still allowing practices like marital rape or maintaining criminal legislation against ‘witchcraft,’ leading to severe penalties.

Sexual violence against women escalates drastically during times of war and conflict, with contemporary examples including war rape and sexual slavery. The grim accounts of sexual violence during conflicts in Armenia, Bangladesh, Bosnia, Rwanda, Congo, and the recent “sexual jihad” by ISIL underscore the profound vulnerability of women in such dire circumstances.

Cultural expressions, particularly clothing and dress codes, also highlight the diverse experiences of women globally. Influenced by local culture, religious tenets, traditions, and fashion, choices about attire vary widely, as do societal ideas about modesty. Laws in many jurisdictions, especially concerning Islamic dress, either mandate or prohibit certain garments, leading to significant controversy.

Fertility rates vary dramatically worldwide, from Niger’s high of 6.62 children per woman to Singapore’s low of 0.82. High fertility rates in Sub-Saharan Africa pose resource challenges, while sub-replacement rates in Western countries contribute to population aging and decline, illustrating the diverse demographic pressures affecting women’s lives.

Family structures have also evolved, particularly in the West, moving from extended to nuclear family living arrangements. There’s been a trend towards non-marital fertility, which, while accepted in some places, is highly stigmatized in others, potentially leading to ostracism, violence, or even honor killings, especially in countries where sex outside marriage remains illegal.

Globally, the social role of the mother varies: some cultures expect mothers with dependent children to remain at home, while in others, mothers frequently return to paid work. Education, a critical determinant of opportunity, has seen significant advancements for women.

While universal education is not yet a global norm, women in many Western countries have surpassed men at various educational levels. In the U.S. in 2005/2006, women earned the majority of associate, bachelor’s, and master’s degrees, and half of doctorates. Global literacy rates for women reached 87% in 2020, though disparities remain, with only 59% of women literate in sub-Saharan Africa.

OECD countries have seen a reduction in the educational gender gap, with younger women significantly more likely to have completed tertiary education than older generations. More women are graduating from university-level programs than men in many OECD countries, and 15-year-old girls often exhibit higher career expectations than boys.

However, challenges persist, particularly in STEM fields, where women account for only 30% of tertiary degrees in science and engineering and 25-35% of researchers. Sociologist Harriet Zuckerman observed that the more prestigious an institute, the harder it is for women to obtain faculty positions. For instance, in 1989, Harvard University tenured its first woman in chemistry, and in 1992, its first in physics.

Women have historically been more likely to start in instructor or lecturer roles, while men more often began in tenured positions. As of 1989, only 40% of women held tenured positions compared to 65% of men, and women constituted only 29% of assistant professors in science and engineering. Even in psychology, where women earn most PhDs, they hold significantly fewer tenured positions.

The multifaceted reality of women’s lives is a testament to both enduring biological foundations and profound societal shaping. From ancient queens and scholars to contemporary scientists and leaders, women have continuously navigated, challenged, and redefined their roles. The journey towards comprehensive understanding and full equality, while marked by significant progress, continues to unfold.

Exploring womanhood requires acknowledging its biological intricacies, appreciating its rich historical and linguistic tapestry, and confronting the persistent social and health disparities that still affect millions. It is a narrative of resilience, adaptation, and an ongoing striving for a future where every woman can thrive, unburdened by historic limitations and empowered by equal opportunity, her inherent worth universally recognized and celebrated.