Embarking on a journey to understand what it means to be a woman is an exploration far richer and more complex than any single definition could ever encompass. It’s a tapestry woven from threads of biology, history, culture, and individual experience, constantly evolving and challenging simplistic notions. Today, we’re going to pull back the curtain on these layers, starting with the very fabric of identity and the biological underpinnings that contribute to the remarkable diversity of women worldwide.

Let’s begin by tracing the very word itself. The English term “woman” has undertaken quite an etymological adventure over the past millennium. It didn’t just pop up overnight. We see its lineage stretching back to “wīfmann” in Old English, then morphing into “wīmmann,” then “wumman,” before settling into its modern spelling. This linguistic evolution tells its own story.

It’s fascinating to consider that in Old English, the word “mann” held a gender-neutral meaning, akin to how we might use “person” or “someone” today. The specific term for ‘woman’ was actually “wīf” or “wīfmann,” which literally translates to ‘woman-person.’ Conversely, a ‘man’ was referred to as “wer” or “wǣpnedmann,” derived from “wǣpn” meaning ‘weapon’ or ‘penis.’ However, a significant shift occurred after the Norman Conquest, when “man” increasingly began to denote a ‘male human,’ eventually replacing “wer” by the late 13th century.

During this linguistic transformation, the consonants /f/ and /m/ in “wīfmann” gradually coalesced, giving us the “woman” we recognize today. Meanwhile, “wīf” itself narrowed its meaning to specifically denote a married woman, becoming what we now know as ‘wife.’ It’s a common, yet mistaken, belief that “woman” shares an etymological root with “womb.” The truth is, “womb” stems from the Old English word “wamb,” meaning ‘belly’ or ‘uterus,’ a term distinct from the origins of “woman.” This little linguistic detour highlights how deeply ingrained and often misunderstood our foundational vocabulary can be.

Beyond etymology, the terminology we use to refer to women also carries significant social weight and has seen considerable shifts. The word “woman” can be employed broadly to signify any female human, or more precisely, an adult female human, distinguishing her from a “girl.” It’s worth remembering that “girl” itself originally meant “young person of either sex” in English, only narrowing to mean a female child around the beginning of the 16th century.

This evolution in usage isn’t merely academic; it reflects broader societal changes. For instance, the colloquial use of “girl” to refer to a young or unmarried woman, while once common, faced strong challenges from feminists in the early 1970s. Their argument was clear: using the word to describe a fully grown woman could be offensive, underscoring a power dynamic that infantilized adult women. As a result, terms like “office girl,” once prevalent, are now largely obsolete, a small but meaningful victory in the battle for respectful language.

Yet, cultural nuances persist. In some societies, particularly those where family honor is closely tied to female virginity, the word “girl” or its equivalent in other languages is still used to refer to a never-married woman. In this context, it functions much like the more-or-less obsolete English terms “maid” or “maiden,” revealing how deeply cultural values can shape linguistic practices and perceptions of age and status. The social sciences, too, have reshaped their understanding of what it means to be a woman since the early 20th century, particularly as women gained more rights and greater workforce representation. Scholarship in the 1970s marked a significant pivot towards focusing on the crucial sex–gender distinction and the social construction of gender, challenging purely biological definitions.

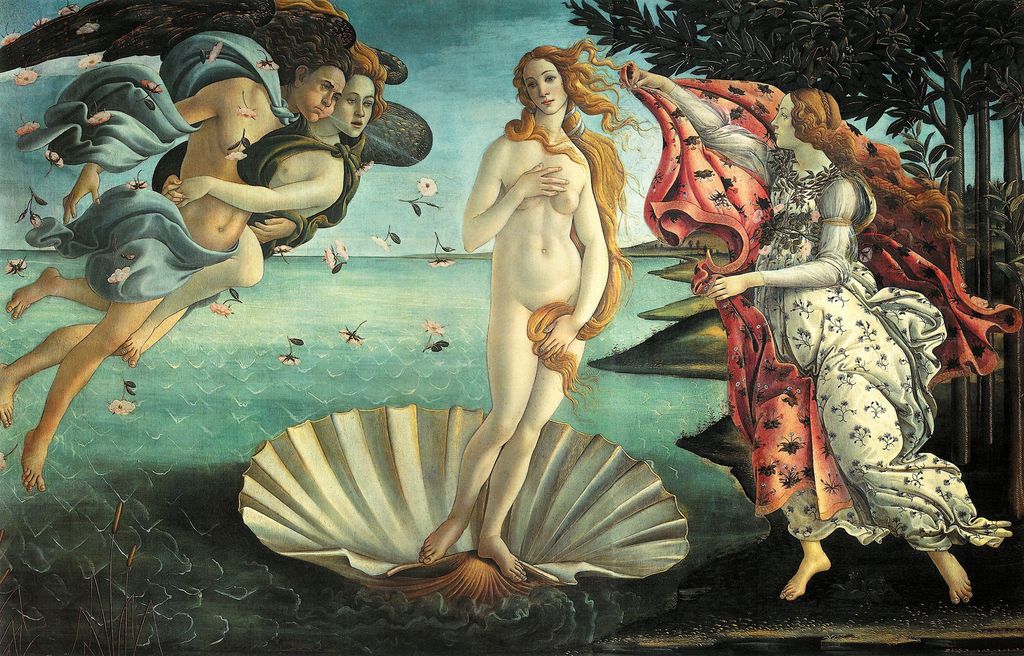

When we talk about the quality of being a woman, several terms come to mind, each with subtle but important differences. “Womanhood” broadly signifies the state of being a woman, a straightforward descriptor of status. “Femininity,” however, refers to a collection of typical female qualities, often associated with a particular attitude towards gender roles—think of Sandro Botticelli’s “The Birth of Venus” (1486, Uffizi) as a classic artistic representation of femininity, drawing on the Roman goddess Venus associated with love, beauty, and fertility. “Womanliness,” while similar to “femininity,” often implies a somewhat different view of gender roles, perhaps more rooted in traditional strength or dignity rather than purely aesthetic or relational qualities. Legally, the age of majority, the point at which a person is considered an adult, is frequently 18, though this varies by country. Biologically, menarche, the onset of menstruation, typically occurs around ages 12–13, marking the physiological capability for pregnancy. Many cultures also mark this transition with rites of passage, from confirmations in some Christian branches to bat mitzvahs in Judaism, or special birthday celebrations like the quinceañera in Latin America.

Diving into the biological realities offers a fascinating contrast to these social constructs. While male and female bodies share many similarities, they also exhibit profound differences, some visible, others hidden within our internal anatomy and genetic makeup. At the very heart of female human biology lies a distinct genetic signature: typically, the cells of female humans contain two X chromosomes, while male humans have an X and a Y chromosome. This genetic blueprint sets the stage for distinct developmental pathways.

During the early stages of fetal development, all embryos present phenotypically female genitalia up until around week 6 or 7. It’s at this critical juncture that a male embryo’s gonads begin to differentiate into testes, a process driven by the action of the SRY gene located on the Y chromosome. In contrast, sex differentiation in female humans proceeds independently of gonadal hormones, following a different, intrinsic pathway. This fundamental genetic distinction also has implications for lineage tracing, as humans inherit mitochondrial DNA exclusively from the mother’s ovum, allowing genealogical researchers to trace maternal lines far back into time.

Puberty in females ushers in a cascade of bodily transformations, enabling sexual reproduction. In response to intricate chemical signals originating from the pituitary gland, the ovaries spring to action, secreting hormones that orchestrate the maturation of the body. This includes noticeable changes such as increased height and weight, the emergence of body hair, the development of breasts, and ultimately, menarche, the onset of menstruation. Most girls experience menarche between the ages of 12 and 13, marking the period when they become biologically capable of becoming pregnant and bearing children.

The process of pregnancy typically requires the internal fertilization of eggs with sperm, either through sexual intercourse or artificial insemination. However, advancements like in vitro fertilization now allow fertilization to occur outside the human body, broadening the possibilities of conception. Humans, like other large mammals, usually give birth to a single offspring per pregnancy, though multiple births, most commonly twins, do occur. What makes human offspring somewhat unique among large mammals is their altricial nature; they are undeveloped at birth and require extensive aid from parents or guardians to reach maturity.

Another distinctive biological milestone for women is menopause, which typically occurs between the ages of 49 and 52. This is the point when menstrual periods permanently cease, signifying the end of the reproductive years. Interestingly, unlike most other mammals, the human lifespan often extends many years beyond menopause. This extended post-reproductive life phase is a subject of biological intrigue. Many biologists propose that this prolonged human lifespan is evolutionarily driven by kin selection, suggesting that grandmothers, for example, play a crucial role in caring for grandchildren and other family members, thereby contributing to the survival and success of their genetic kin. While kin selection is a prominent theory, other explanations for this unique aspect of human female longevity have also been put forth.

When we consider the morphological and physiological characteristics, the female body is clearly distinguished by its reproductive system and secondary sex characteristics. The female sex organs are, of course, central to reproduction, while secondary sex characteristics play roles in breastfeeding and mate attraction. As placental mammals, human mothers carry the fetus in the uterus, with the placenta facilitating vital nutrient and waste exchange between mother and child. Breastfeeding, in turn, allows mothers to nourish their newborns with milk, a distinguishing characteristic of mammals that is produced by the mammary glands, which are hypothesized to have evolved from apocrine-like glands.

The prominence of mature female breasts, often larger than in most other mammals, is not strictly necessary for milk production and is widely believed to be at least partially a result of sexual selection. Estrogens, the primary female sex hormones, profoundly influence a female’s body shape. While present in both men and women, their levels are considerably higher in women, particularly during reproductive age. Beyond other functions, estrogens are key drivers in the development of female secondary sexual characteristics, such as breasts and the widening of hips during puberty. Conversely, the presence of testosterone in a pubescent female can work against estrogen’s effects, inhibiting breast development and promoting muscle and facial hair.

The differences extend to the circulatory system as well. Women typically have a lower hematocrit, which is the volume percentage of red blood cells in the blood, compared to men. This difference is attributed to lower testosterone levels in women, as testosterone stimulates the kidneys to produce erythropoietin, a hormone that boosts red blood cell production. The normal hematocrit level for women is 36% to 48%, compared to 41% to 50% for men. Similarly, women’s normal hemoglobin levels range from 12.0 to 15.5 g/dL, while men’s are 13.5 to 17.5 g/dL. Even the heart exhibits sex-specific differences: women’s hearts have finer-grained textures in the muscle compared to men’s, and their overall shape and surface area also differ when body size and age are controlled. Furthermore, an intriguing finding is that women’s hearts appear to age more slowly than men’s.

Globally, there’s a slight imbalance in sex distribution at birth, with girls born slightly less frequently than boys, at a ratio of approximately 1:1.05. As of 2015, the overall human population reflected this, with roughly 1018 men for every 1000 women. It’s also vital to acknowledge the existence of intersex women, individuals born with sex characteristics that don’t fit typical notions of female biology, often presenting with ambiguous genitalia. Most individuals with ambiguous genitalia are assigned female at birth, and it’s important to note that most intersex women identify as cisgender. However, the medical practices surrounding the assignment of a binary female sex to intersex youth are often a subject of controversy. Some intersex conditions are associated with typical rates of female gender identity, while others are linked to substantially higher rates of identifying as LGBT compared to the general population, highlighting the complex interplay of biology, identity, and societal categorization.

This brings us to the nuanced discussion of sexuality and gender. Most women are heterosexual, meaning they are sexually attracted to men, and most are cisgender, meaning their female sex assignment at birth aligns with their female gender identity. However, human female sexuality and attraction are highly variable, influenced by a multitude of factors, including evolved predispositions, personality, upbringing, and culture. While heterosexual women constitute the majority, significant minorities identify as lesbian or bisexual, reflecting the broad spectrum of human attraction.

Most cultures operate within a gender binary, recognizing two genders: women and men. Yet, some cultures acknowledge a third gender, demonstrating the diverse ways human societies categorize identity. Femininity, also known as womanliness or girlishness, refers to a collection of attributes, behaviors, and roles generally associated with women and girls. While femininity is largely understood as a socially constructed concept, it’s also acknowledged that some behaviors considered feminine may have biological influences. The extent to which femininity is shaped by biology versus social conditioning remains a subject of ongoing debate, underscoring its complex nature. It’s crucial to distinguish femininity from the biological female sex, as both men and women can exhibit feminine traits.

The majority of women are cisgender, meaning their female sex assigned at birth aligns seamlessly with their female gender identity. However, it’s increasingly recognized that some women are transgender, having been assigned male at birth. Transgender women may experience gender dysphoria, which is the distress arising from the discrepancy between an individual’s gender identity and their sex assigned at birth. This dysphoria can be addressed through gender-affirming care, which may involve both social and medical transitions. Social transition can encompass changes such as adopting a new name, hairstyle, clothing, and pronouns that align with their affirmed female gender identity.

A significant aspect of medical transition for many trans women is feminizing hormone therapy. This treatment induces the development of female secondary sex characteristics, such as breast growth, the redistribution of body fat to create a more typically female silhouette, and a lower waist-hip ratio. For some, medical transition may also include gender-affirming surgery, where a trans woman might undergo one or more feminizing procedures to achieve anatomy that is typically gendered female. Just like cisgender women, trans women also encompass the full spectrum of sexual orientations, reflecting the rich diversity within womanhood itself.

The journey of understanding women continues beyond these foundational definitions and biological realities into the intricate realm of health. While some health factors uniquely affect women primarily due to reproduction, scientific inquiry continues to uncover subtle sex differences across all scales, from the molecular to the behavioral. Untangling the effects of inherent biological factors from those of the surrounding environment is a complex task. Nevertheless, it’s understood that sex chromosomes and hormones, alongside sex-specific lifestyles, metabolism, immune system function, and environmental sensitivities, all contribute to observed sex differences in physiology, perception, and cognition. This leads to distinct responses to drugs and varying thresholds for diagnostic parameters in women compared to men. Moreover, some diseases predominantly affect or are exclusively found in women, such as lupus, breast cancer, cervical cancer, or ovarian cancer. The medical field dedicated to female reproduction and reproductive organs is, quite appropriately, called gynecology, or the “science of women,” a testament to the specialized care and understanding required for women’s unique health needs.

Having laid the groundwork in understanding the multifaceted nature of what it means to be a woman, from etymology to biology and the nuances of identity, let’s now turn our gaze to the broader societal landscape. Womanhood, as we’ve seen, is not merely a biological state but a dynamic interplay with history, culture, and the evolving challenges and triumphs within society. From navigating health disparities to asserting fundamental rights, and from shaping historical narratives to influencing the future of education and leadership, women’s journey is one of continuous evolution and profound impact.

**Woman in Society: Navigating Historical Roles, Health Challenges, and Cultural Realities**

When we consider the health of women, it’s clear that certain factors uniquely impact them, often most dramatically in areas related to reproduction. However, the scientific community is continuously uncovering subtle yet significant sex differences that span every scale, from the molecular intricacies of our cells to broad behavioral patterns. Disentangling what’s inherently biological from what’s shaped by our environment is a complex puzzle, but it’s understood that our sex chromosomes, hormones, lifestyle choices, metabolism, immune system function, and even our sensitivity to environmental factors all play a part. These distinctions lead to women often having different responses to medications and varying thresholds for diagnostic parameters compared to men. Beyond these subtle differences, some diseases, like lupus, breast cancer, cervical cancer, or ovarian cancer, predominantly or even exclusively affect women. This is why the medical field dedicated specifically to female reproduction and reproductive organs, gynecology, is so vital—it truly is the “science of women,” acknowledging their unique health needs.

A particularly poignant area within women’s health is maternal mortality, a tragic statistic that speaks volumes about global health inequities. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines maternal mortality as “the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management but not from accidental or incidental causes.” The numbers are stark: in 2008, over 500,000 women died annually from pregnancy and childbirth complications. Beyond the fatalities, at least seven million women experienced serious health problems, and 50 million more suffered adverse health consequences after childbirth. The WHO has actively championed midwife training through initiatives like Action for Safe Motherhood, recognizing that strengthening midwifery skills is paramount to improving maternal and newborn health services.

The disparities in maternal mortality are glaringly geographic. In 2017, a staggering 94% of maternal deaths occurred in low and lower middle-income countries. Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia bore the brunt of this burden, accounting for approximately 86% of all maternal deaths, with Sub-Saharan Africa alone responsible for about 66% and Southern Asia for around 20%. The main culprits are often preventable or treatable conditions: pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, unsafe abortion, pregnancy complications exacerbated by malaria and HIV/AIDS, and severe bleeding and infections following childbirth. In stark contrast, countries like most of Europe, Australia, Japan, and Singapore are considered remarkably safe places for childbirth, highlighting how much progress is still needed globally.

Shifting focus to overall longevity, it’s a well-known fact that women generally enjoy a longer life expectancy than men, an advantage that often begins right at birth, with newborn girls demonstrating higher survival rates in their first year. Globally, women live six to eight years longer than men, though this varies significantly by region and circumstance. For instance, discrimination against women in some parts of Asia has unfortunately led to a lower female life expectancy, reversing this common trend. The reasons for this general longevity advantage are believed to be a mix of biological factors and gendered behavioral differences. Women are statistically less likely to engage in unhealthy behaviors such as smoking or reckless driving, which translates to fewer preventable premature deaths. However, in some developed countries, this gap is starting to narrow, a phenomenon attributed both to women adopting more detrimental health behaviors, particularly an increased rate of tobacco smoking, and improved health outcomes among men, for example, less cardiovascular disease. It’s a crucial point, as the WHO reminds us, that the “extra years of life for women are not always lived in good health.”

Intricately linked to health, and indeed to autonomy, are reproductive rights. These are fundamental legal rights and freedoms concerning reproduction and reproductive health. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) eloquently states that “the human rights of women include their right to have control over and decide freely and responsibly on matters related to their sexuality, including sexual and reproductive health, free of coercion, discrimination and violence.” This foundational principle emphasizes mutual respect, consent, and shared responsibility in sexual relations and reproduction, affirming the full integrity of the person.

Despite this clear articulation of rights, the reality on the ground for many women remains challenging, particularly concerning abortion access. The World Health Organization reported that between 2010 and 2014, an astonishing 56 million induced abortions occurred worldwide each year, representing 25% of all pregnancies. Of these, approximately 25 million were deemed unsafe. The human cost of unsafe abortions is horrific: about 30 women die for every 100,000 unsafe abortions in developed regions, a number that skyrockets to 220 deaths per 100,000 in developing regions, and a devastating 520 deaths per 100,000 in sub-Saharan Africa. The WHO attributes these preventable deaths to a multitude of systemic barriers: restrictive laws, poor availability of services, high costs, pervasive stigma, conscientious objection from healthcare providers, and unnecessary requirements such as mandatory waiting periods, misleading counseling, third-party authorization, and medically unnecessary tests that dangerously delay care.

Delving into history, it becomes abundantly clear that women have always been central to human civilization, often in roles far more influential and pioneering than traditional narratives might suggest. Consider the earliest women whose names have been etched into history: Neithhotep, circa 3200 BCE, wife of Narmer and possibly the first queen of ancient Egypt. Then there’s Merneith, around 3000 BCE, a consort and regent of ancient Egypt, who may even have ruled in her own right. Peseshet, around 2600 BCE, was a physician in Ancient Egypt, demonstrating early female professional expertise. Puabi, circa 2600 BCE, also known as Shubad, was a queen of Ur whose elaborate tomb with expensive artifacts speaks volumes about her status. Kugbau, circa 2500 BCE, a taverness from Kish, was chosen to rule Sumer and later deified. Tashlultum, circa 2400 BCE, was an Akkadian queen and mother of the renowned Enheduanna.

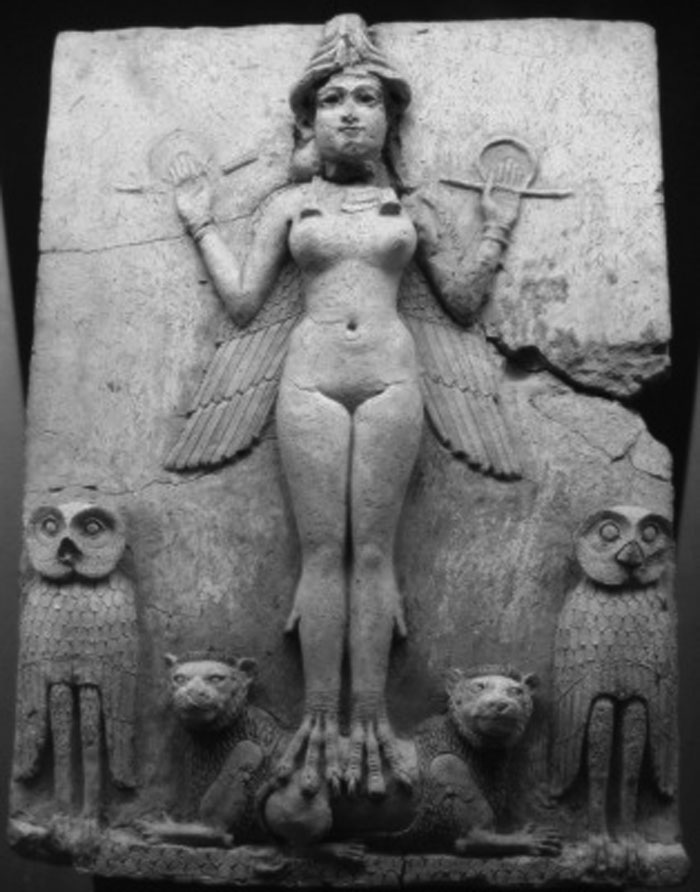

And speaking of Enheduanna, circa 2285 BCE, she stands out as the high priestess of the Moon God in Ur and is possibly the first known poet and first named author of either gender—a truly monumental figure in intellectual history. We also have Shibtu, circa 1775 BCE, consort and queen of the Syrian city-state of Mari, who governed as regent during her husband’s absence, wielding extensive administrative powers. These historical figures remind us that leadership, intellectual prowess, and societal influence have been part of women’s reality for millennia. It’s also interesting to note that the glyph (♀) symbolizing the female sex is the same as that for the Roman goddess Venus or Greek Aphrodite, who was associated with love, beauty, and fertility. In ancient alchemy, this Venus symbol even represented copper, further linking it to concepts of femininity.

Moving to culture and gender roles, we see how dramatically these have shifted, particularly in recent history. At earlier points, children’s occupational aspirations were rigidly gender-determined from a young age. Traditionally, middle-class women were largely confined to domestic tasks, focusing on childcare. For women from poorer backgrounds, however, economic necessity often compelled them to seek employment outside the home, even if they might have preferred domestic duties. The occupations available to them were generally lower paying than those accessible to men.

Significant changes in the labor market opened up new avenues. The transition from demanding, often “dirty” factory jobs to “cleaner,” more respectable office positions, which required more education, began to reshape attitudes toward women at work. This shift was a catalyst for a revolution, allowing women to become increasingly career and education oriented. While strides have been made, societal expectations have historically placed a heavy burden on professional women. As sociologist Harriet Zuckerman observed, even as institutions in the 1980s tried to equalize conditions, professional women were still typically seen as primarily responsible for domestic labor and childcare. This significantly limited the time and energy they could devote to their careers. Early 20th-century U.S. women’s colleges even required female faculty to remain single, believing a woman couldn’t manage two full-time professions simultaneously. As Schiebinger succinctly puts it, “Being a scientist and a wife and a mother is a burden in society that expects women more often than men to put family ahead of career.

Thanks to a combination of economic changes and the relentless efforts of the feminist movement, women in many societies have, in recent decades, gained access to careers far beyond the traditional homemaker role. Yet, modern women in Western society continue to face persistent challenges across various spheres, including the workplace, education, issues of violence, healthcare access, political participation, and the complexities of motherhood. Sexism remains a major concern and barrier for women almost universally, though its manifestations, public perception, and severity vary greatly between different societies and social classes. The Gender Parity Index in school enrollment, for instance, highlights these global disparities. Interestingly, girls tend to exhibit higher reading skills, and while gender pay gaps vary by country and age group, they are a pervasive reality.

Religion, too, has played a profound role in defining and often limiting women’s roles. Many particular religious doctrines stipulate specific gender roles, regulate the spiritual authority of women, govern social and private interactions between the sexes, dictate appropriate dressing attire for women, and address various other issues affecting women’s position in society. In numerous countries, these religious teachings deeply influence criminal law or family law—think, for example, of Sharia law. The intricate relationship between religion, law, and gender equality is a consistent topic of discussion among international organizations, underscoring its global significance.

One of the most insidious and widespread challenges women face is violence. The UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women defines it broadly as “any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.” This definition further identifies three primary forms of such violence: that occurring within the family, that within the general community, and that perpetrated or condoned by the State. Crucially, the declaration unequivocally states that “violence against women is a manifestation of historically unequal power relations between men and women.

This violence remains a pervasive global problem, particularly outside Western societies, often fueled by patriarchal social values, a lack of adequate protective laws, or a failure to enforce existing ones. Social norms in many parts of the world actively hinder progress. Consider, for example, UNICEF surveys revealing that in countries like Afghanistan and Jordan, up to 90% of women aged 15-49 believe a husband is justified in hitting his wife under certain circumstances. Similarly, a 2010 Pew Research Center survey found that stoning as a punishment for adultery was supported by 82% of respondents in Egypt and Pakistan.

Specific forms of violence disproportionately affecting women are horrifyingly diverse and widespread. These include female genital mutilation (FGM), sex trafficking, forced prostitution, forced marriage, rape, sexual harassment, honor killings, acid throwing, and dowry-related violence. While laws and policies vary by jurisdiction – the European Union, for instance, has directives on sexual harassment and human trafficking – governments themselves can be complicit, such as when stoning is used as a legal punishment, primarily targeting women accused of adultery. Historically, even more brutal forms of violence were prevalent, like the burning of witches, the sacrifice of widows (sati), and foot binding. The prosecution of women accused of witchcraft has a long and dark tradition, with witch trials common in early modern Europe and its colonies. Disturbingly, today, regions such as parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, rural North India, and Papua New Guinea still see serious violence against women accused of witchcraft, with some countries even having criminal legislation against the practice, Saudi Arabia famously punishing witchcraft by death, as tragically seen in a 2011 beheading. Furthermore, certain forms of violence, like marital rape, have only recently been recognized as criminal offenses in some jurisdictions and remain permissible in many others. While the Western world has seen a trend towards gender equality within marriage and the prosecution of domestic violence, in many parts of the world, women still lose significant legal rights upon entering marriage.

Times of war and armed conflict are particularly dangerous for women, witnessing a drastic increase in sexual violence, most often in the form of war rape and sexual slavery. Tragic contemporary examples include the systematic rapes during the Armenian Genocide, the Bangladesh Liberation War, the Bosnian War, the Rwandan genocide, the Second Congo War, and the armed conflict in Colombia. More recently, the horrific “sexual jihad” perpetrated by ISIL led to the sale of 5,000–7,000 Yazidi and Christian girls and children into sexual slavery during genocidal acts, with some victims driven to jump to their deaths from Mount Sinjar.

Clothing, fashion, and dress codes, while seemingly superficial, are deeply intertwined with culture, religion, and social norms, often reflecting societal control over women. Women worldwide dress in myriad ways, influenced by local culture, religious tenets, traditions, social norms, and fashion trends. Ideas about modesty vary wildly, and in many jurisdictions, laws dictate what women may or may not wear. This is especially evident with Islamic dress, where some places legally mandate the wearing of the headscarf, while others, like France, forbid or restrict certain hijab attire, such as the burqa or face coverings, in public. Both types of laws—those mandating and those prohibiting specific articles of dress—are highly controversial, sparking global debates about individual freedom and cultural imposition.

When we look at fertility and family life, we uncover significant global variations. The total fertility rate (TFR), which is the average number of children born to a woman over her lifetime, differs dramatically across regions. In 2016, Niger boasted the highest estimated TFR at 6.62 children per woman, while Singapore recorded the lowest at a mere 0.82 children per woman. While most Sub-Saharan African countries contend with high TFRs, leading to concerns about resource scarcity and overpopulation, most Western countries are currently experiencing sub-replacement fertility rates, which may lead to population aging and decline.

Family structures have also undergone profound transformations in recent decades. In the West, there’s been a clear trend away from extended family living arrangements towards nuclear family units. Alongside this, there’s been a shift from marital fertility to non-marital fertility, meaning more children are born to cohabiting couples or single women. While births outside marriage are common and fully accepted in some parts of the world, elsewhere they remain highly stigmatized, often leading to ostracism, violence from family members, and in extreme cases, even honor killings for unmarried mothers. Furthermore, sex outside marriage remains illegal in many countries, including Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran, Kuwait, Maldives, Morocco, Oman, Mauritania, United Arab Emirates, Sudan, and Yemen. The social role of the mother also varies immensely: in many cultures, mothers with dependent children are expected to remain at home and dedicate all their energy to child-rearing, while in other places, mothers most often return to paid work.

Education is another critical domain where women have made remarkable strides, yet persistent inequalities remain. Single-sex education, though traditionally dominant, continues to be highly relevant. Universal education, meaning state-provided primary and secondary education irrespective of gender, is not yet a global norm, even if it’s taken for granted in most developed countries. In some Western countries, women have now surpassed men at many levels of education. For example, in the United States during the 2005/2006 academic year, women earned 62% of associate degrees, 58% of bachelor’s degrees, 60% of master’s degrees, and 50% of doctorates. While global literacy rates in 2020 showed women at 87% compared to men at 90%, the disparity in sub-Saharan Africa was starker, with only 59% of women being literate.

The educational gender gap in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries has narrowed significantly over the last three decades. Younger women today are far more likely to have completed a tertiary qualification; in 19 of the 30 OECD countries, more than twice as many women aged 25 to 34 have completed tertiary education than women aged 55 to 64. Moreover, in 21 of 27 OECD countries with comparable data, the number of women graduating from university-level programs is equal to or even exceeds that of men. Intriguingly, 15-year-old girls tend to have much higher career expectations than boys of the same age. However, despite women constituting more than half of university graduates in several OECD countries, they receive only 30% of tertiary degrees in science and engineering fields and account for only 25% to 35% of researchers in most OECD nations. Research indicates that while women are studying at prestigious universities at the same rate as men, they are not being given the same opportunities to join the faculty. Sociologist Harriet Zuckerman noted that the more prestigious an institution, the more challenging and time-consuming it becomes for women to secure a faculty position. Harvard University, for example, tenured its first woman in chemistry in 1989 and its first in physics in 1992. Zuckerman also observed that women were more likely to begin their professional careers as instructors and lecturers, whereas men were more likely to start in tenure positions. As of 1989, Smith and Tang reported that 65% of men held tenured positions compared to only 40% of women, and only 29% of all scientists and engineers employed as assistant professors in four-year colleges and universities were women. It’s worth remembering that the Soviet Union, in the 1960s, had 40% of chemistry PhDs awarded to women, demonstrating that such progress is possible.

In the realm of government and politics, the 20th century marked a pivotal period where restrictions on women’s public life began to loosen across many societies. This allowed women wider access to careers and the pursuit of higher education, which in turn slowly paved the way for increased participation in political processes. While the exact statistics on women in government aren’t detailed in our immediate context, the general trajectory has been one of growing presence, moving from historical exclusion to increasingly influential roles. However, as noted earlier, modern women in Western society, despite these advances, still face challenges across various spheres, including politics, suggesting that the journey towards full and equal representation in governance remains ongoing.

Finally, women’s indelible contributions to science, literature, and art are immense, even if often historically overlooked. In science and medicine, as we touched upon, fields like gynecology are dedicated to women’s unique health needs. While women only make up a minority of scientists and engineers in many OECD countries today, the historical example of the Soviet Union in the 1960s, where 40% of chemistry PhDs went to women, shows that high female participation in scientific fields is achievable. The challenges women face in academia, particularly in obtaining prestigious faculty positions, persist, as highlighted by the observations of Harriet Zuckerman. Yet, their foundational and ongoing work is undeniable. In literature, figures like Enheduanna, possibly the world’s first known author and poet, establish a legacy of female literary genius stretching back millennia. While specific examples for music aren’t detailed, it’s understood that women have enriched every facet of artistic expression, contributing to the vibrant tapestry of human culture through their creativity and vision across all disciplines of literature, art, and music. This rich legacy underscores that women are not merely subjects of history and societal study, but active, powerful shapers of human experience and progress.