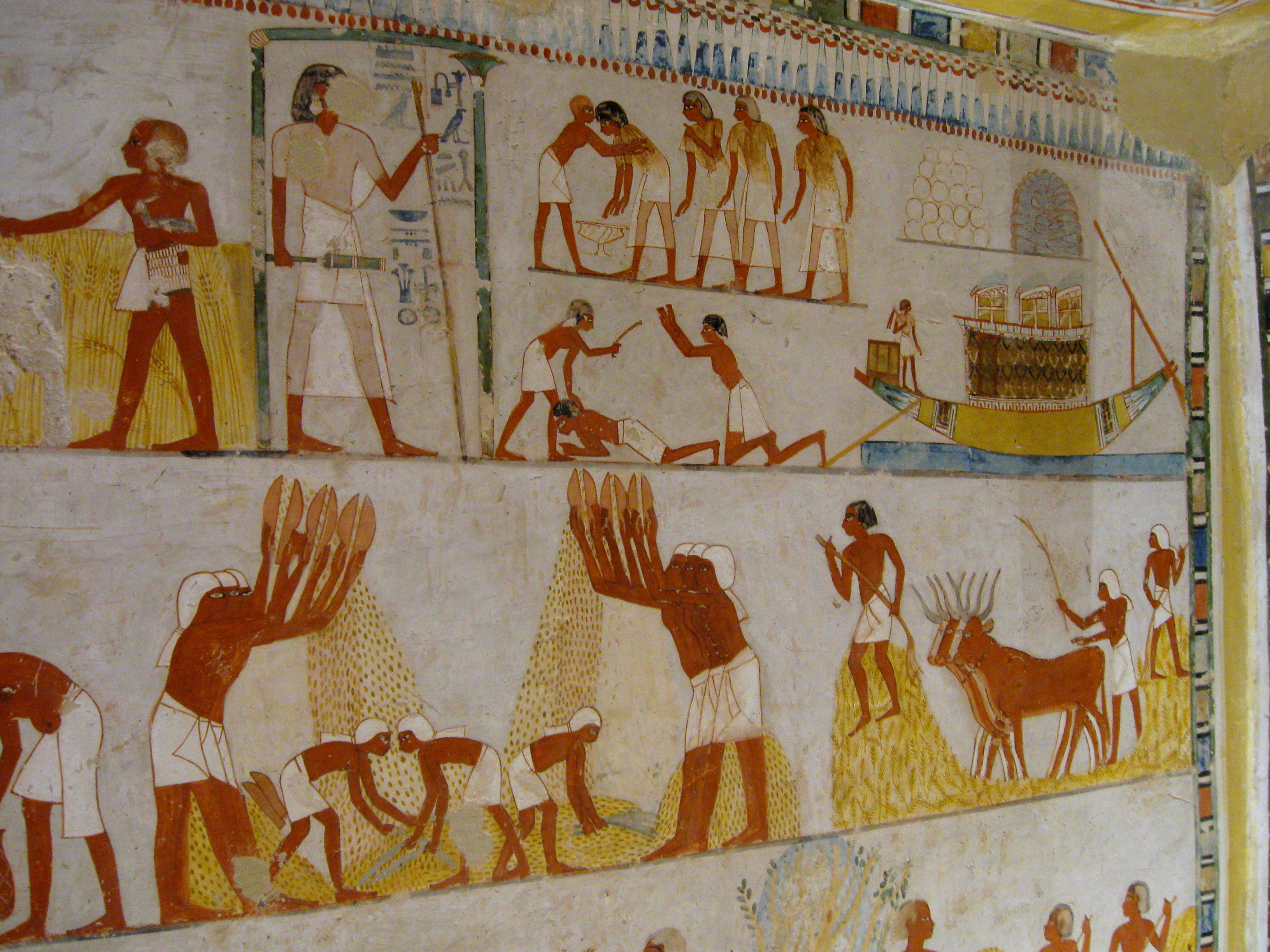

The allure of ancient civilizations, with their monumental constructions and enigmatic achievements, has captivated humanity for millennia. From the towering Great Pyramids of Egypt to the sophisticated urban centers of long-lost empires, we often gaze upon these wonders and ponder the ingenuity of those who came before us. How did they achieve such feats with seemingly rudimentary tools, and what secrets lie buried beneath the sands of time? This quest for answers drives one of humanity’s most fascinating disciplines: archaeology.

Archaeology, in its essence, is a meticulous journey into the past, a systematic study of human activity brought to light through the material remains they left behind. It’s about reconstructing entire lifeways, understanding cultural shifts, and chronicling the grand narrative of human development. This vital field helps us bridge the vast chasm of prehistory, where written records are absent, providing the sole window into over 99% of our collective human story. As we explore the evolution of archaeology, from its nascent beginnings to its modern scientific methodologies, we will see how its relentless curiosity lays the foundation for deciphering the complex tapestry of our shared past, including the astonishing “ingenuity” of ancient builders.

1. **The Enduring Quest: Defining and Delineating the Scope of Archaeology**At its heart, archaeology is a profound act of historical detective work, driven by the tangible evidence of material culture. It stands as the study of human activity, painstakingly pieced together through the recovery and analysis of everything from discarded tools and monumental architecture to subtle changes in landscapes and preserved organic remains. The vast tapestry of the archaeological record encompasses artifacts, architecture, biofacts, sites, and cultural landscapes, ensuring a comprehensive pursuit of understanding past lives.

Archaeology occupies a unique position within academia, considered simultaneously a social science, for its empirical methodologies and focus on societal structures, and a branch of the humanities, for its interpretive nature. While often an independent academic discipline, it also maintains strong cross-disciplinary connections with anthropology, history, and geography, highlighting its crucial role in understanding human evolution and ancient societies.

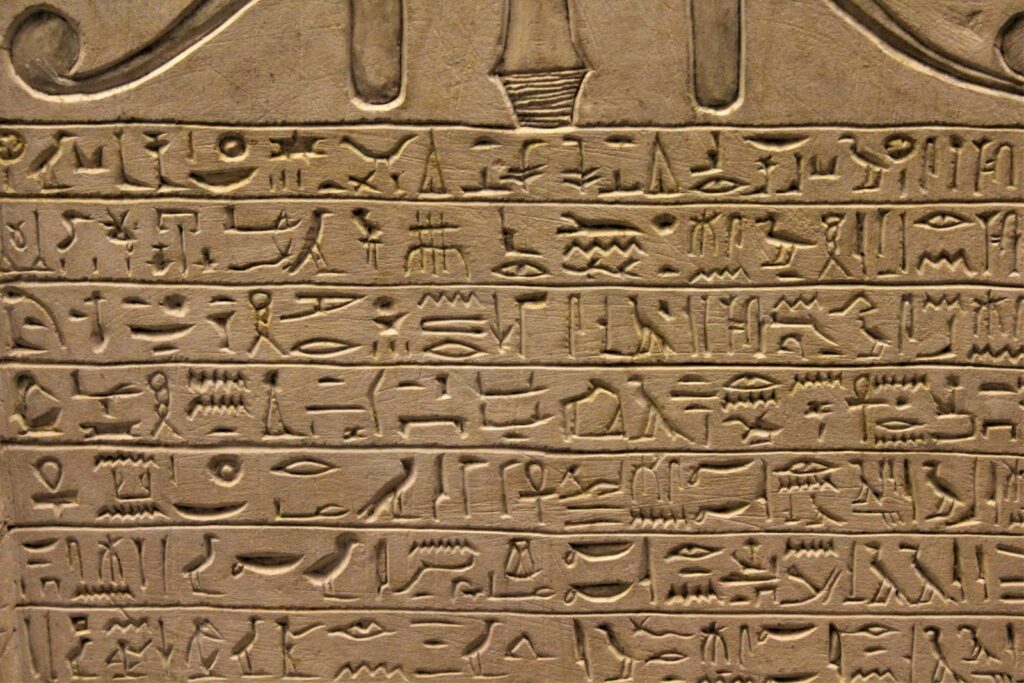

The temporal scope of archaeological inquiry is immense, stretching back across millions of years, from the first stone tools at Lomekwi 3.3 million years ago, up until recent decades. Distinct from palaeontology, archaeology is particularly important for illuminating prehistoric societies, for which no written records exist, covering over 99% of the human past. Its goals range from understanding culture history to reconstructing past lifeways and explaining societal changes. The term “archaeology,” derived from Greek, means “the study of ancient history.”

2. **Nabonidus: The First Archaeologist and an Early Quest for the Past**Long before archaeology solidified into a modern academic discipline, the seeds of antiquarian interest were sown in ancient Mesopotamia by King Nabonidus, ruler of Babylonia around 550 BC. Often hailed as “the first archaeologist,” Nabonidus demonstrated an extraordinary curiosity for the past, undertaking systematic efforts to unearth and understand the relics of earlier civilizations. His endeavors were driven by a desire to connect with and restore the legacies of his predecessors, a practice that resonates strongly with core tenets of modern archaeological investigation.

A remarkable testament to Nabonidus’s pioneering spirit is his discovery and analysis of a foundation deposit belonging to Naram-Sin, an Akkadian Empire ruler from approximately 2200 BC. This cuneiform account details Nabonidus’s excavations to locate the foundation deposits of significant temples in Sippar and Harran. His work went beyond mere discovery; he meticulously recorded his findings and then had these ancient structures restored to their former glory, demonstrating an early form of archaeological conservation.

What truly distinguishes Nabonidus as a proto-archaeologist was his unprecedented attempt to date an archaeological artifact. During his dedicated search for Naram-Sin’s temple, he made an effort to assign a chronological value to his finds. Although his estimate was inaccurate by about 1,500 years, it was an incredibly sophisticated and insightful attempt for his era, highlighting a foundational principle of archaeology: understanding when things happened is as crucial as understanding what happened.

Read more about: Archaeology’s Enduring Mysteries: A Deep Dive into Humanity’s Past Through the Lens of Material Culture

3. **The Genesis of a Science: Tracing the Evolution of Antiquarianism**The scientific discipline of archaeology emerged from a rich, older tradition known as antiquarianism, which flourished globally. Antiquarians were scholars who immersed themselves in history, paying particular attention to tangible remnants of the past—ancient artifacts, manuscripts, and historical sites. Their focus was rooted in empirical evidence, epitomized by Richard Colt Hoare’s motto: “We speak from facts, not theory.” This commitment to observable data laid the intellectual groundwork for a more formalized scientific approach.

Beyond Europe, similar scholarly pursuits were underway. In Imperial China during the Song dynasty (960–1279), figures like Ouyang Xiu and Zhao Mingcheng established a vibrant tradition of Chinese epigraphy, investigating and analyzing ancient bronze inscriptions. Shen Kuo, in 1088, even criticized contemporaries for misattributing vessels and attempting to revive them without discerning original function, showcasing an early form of critical material analysis, though it remained a branch of historiography.

The European Renaissance saw a significant surge in philosophical interest in Greco-Roman material remains. Cyriacus of Ancona, a tireless Italian humanist and antiquarian, was often called ‘pater antiquitatis’ or “father of classical archaeology.” His extensive travels throughout Greece and the Eastern Mediterranean led him to meticulously record ancient buildings, statues, and inscriptions, including the Parthenon, Delphi, and the Egyptian pyramids. His detailed diary, “Commentaria,” became a vital record, setting a precedent for documentation.

Figures like Flavio Biondo, who created a systematic guide to ancient Rome’s ruins, and later English antiquarians John Leland and William Camden, conducted comprehensive surveys. These systematic efforts to document and interpret material remains were crucial steps. The term “archaeologist,” first cited in 1824, eventually replaced “antiquary,” signaling the formal emergence of a distinct academic profession dedicated to uncovering and interpreting our ancient heritage.

4. **Unveiling the Earth’s Secrets: The First Systematic Excavations**The early stirrings of formal archaeological excavation marked a pivotal shift from mere curiosity to systematic inquiry. One of the earliest and most iconic sites to undergo such investigation was Stonehenge, alongside other megalithic monuments in England. John Aubrey, a pioneer archaeologist active between 1626 and 1697, meticulously recorded numerous megalithic and other field monuments in southern England. His analytical approach was remarkably ahead of its time, as he attempted to chart the chronological stylistic evolution of various material forms, demonstrating an early awareness of systematic typology and dating.

Simultaneously, a dramatic discovery began unfolding in Italy. The Spanish military engineer Roque Joaquín de Alcubierre initiated excavations in the ancient towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum, tragically buried by Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. These pioneering excavations commenced in Herculaneum in 1738 and in Pompeii in 1748. The unearthing of entire towns, remarkably preserved with utensils, frescoes, and even human shapes, sent shockwaves throughout Europe, offering an unprecedented window into daily Roman life and fueling interest in classical antiquity.

Despite the groundbreaking nature of these early endeavors, the techniques employed were often haphazard by modern standards. Crucial concepts that form the bedrock of contemporary archaeology, such as stratigraphy—the understanding of successive depositional layers—and context—the relationship of an artifact to its surroundings—were largely overlooked. These early excavators, while driven by discovery, had yet to develop the systematic rigor that would characterize later scientific archaeology, though their efforts undeniably ignited public imagination.

5. **Johann Joachim Winckelmann: The Prophet of Scientific Archaeology and Art History**In the mid-18th century, a transformative figure emerged in Rome: the German Johann Joachim Winckelmann. He devoted himself with unparalleled zeal to the study of Roman antiquities, acquiring an unrivalled depth of knowledge concerning ancient art. His intellectual rigor and keen eye for detail were instrumental in elevating the study of art and archaeology from mere connoisseurship to a more scientific and systematic endeavor.

Winckelmann’s groundbreaking insights were solidified by his visits to the archaeological excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum. Witnessing firsthand the unearthed wonders, he was able to apply his burgeoning theories to tangible evidence. He is widely recognized as one of the founders of scientific archaeology because he was among the first to apply categories of style on a large, systematic basis to the history of art, allowing for a structured understanding of artistic evolution.

One of Winckelmann’s most enduring contributions was his pioneering effort to separate Greek art into distinct periods and time classifications. By meticulously analyzing stylistic changes and attributing them to specific chronological phases, he provided a crucial framework for understanding the development of ancient aesthetics and culture. His work earned him the dual accolades of being called both “The prophet and founding hero of modern archaeology” and the undisputed “father of the discipline of art history.”

6. **Laying the Foundations: The Development of Archaeological Method with Stratigraphy and Typology**

The 19th century marked a crucial turning point in archaeology, transforming it into a rigorous science through foundational methodologies. Among the most significant achievements was the systematic application of stratigraphy, a concept borrowed from geology. Archaeologists, recognizing that layers of human occupation corresponded to chronological sequences, understood that more recent layers lay above older ones. This insight revolutionized dating and contextual understanding, providing a reliable framework for reconstructing the past.

Parallel to stratigraphy, the concept of typology emerged as another powerful analytical tool, involving arranging artifacts by type and then chronologically. William Cunnington, often called the “father of archaeological excavation,” undertook meticulous excavations in Wiltshire from around 1798. His precise recordings of Neolithic and Bronze Age barrows, and the terms he used, are still employed today, helping to create ordered sequences of material culture and trace technological evolution.

This systematic arrangement of artifacts by typology, designed to highlight evolutionary trends, proved enormously significant for accurately dating objects and understanding cultural development. In the third and fourth decades of the 19th century, figures like Jacques Boucher de Perthes and Christian Jürgensen Thomsen began to apply these principles. Thomsen’s influential “three-age system”—Stone Age, Bronze Age, Iron Age—provided a broad, typological framework for European prehistory, demonstrating how material culture could signify distinct periods of human development. These innovations laid the essential groundwork for more scientific investigations.

7. **William Flinders Petrie: Pioneering Modern Egyptology and the Great Pyramid’s Secrets**Among archaeological luminaries, William Flinders Petrie holds a preeminent position, often justifiably called the “Father of Archaeology” for his meticulous approach and profound impact on the discipline. His work in Egypt and Palestine set new standards for archaeological recording and analysis, emphasizing an unprecedented level of detail. Petrie famously remarked, “I believe the true line of research lies in the noting and comparison of the smallest details,” transforming the field from treasure hunting to a rigorous scientific endeavor.

Petrie’s most revolutionary contribution was his development of “sequence dating,” a system for dating archaeological layers based on pottery and ceramic findings. By observing gradual stylistic changes in pottery within successive stratigraphic layers, he could establish relative chronologies for sites where written records were absent or incomplete. This method revolutionized the chronological basis of Egyptology, allowing for accurate sequencing of ancient Egyptian dynasties and cultural periods, and providing an indispensable tool for understanding their vast history.

Crucially, Petrie was the first to undertake a truly scientific investigation of the Great Pyramid in Egypt during the 1880s. His rigorous, systematic measurements and observations provided empirical data for a far more accurate understanding of its construction, engineering, and astronomical alignments. His painstaking efforts debunked numerous myths and laid the foundation for all subsequent scientific research into the pyramids, providing critical insights into the incredible organizational and technical capabilities of the ancient Egyptians.

Beyond his personal discoveries, Petrie was also a formidable mentor, nurturing an entire generation of Egyptologists, including Howard Carter, who achieved global fame for discovering Tutankhamun’s tomb. Petrie’s legacy thus extends far beyond his own findings; he cultivated the intellectual lineage that would continue to unlock the profound secrets of ancient Egypt.

The scientific journey into humanity’s past, meticulously charted by pioneering minds and refined through groundbreaking techniques, continues to evolve. While early archaeologists laid the essential groundwork, the 20th century and beyond witnessed an explosion of theoretical advancements and technological innovations, allowing us to peer deeper into ancient civilizations and decode their mysteries with unprecedented precision. From the systematic recovery of every fragment to the sophisticated mapping of landscapes from the sky, modern archaeology continuously redefines our understanding of human ingenuity and the incredible capabilities of past societies, even those whose accomplishments, like the Great Pyramids, often defy simple explanation. This next chapter delves into the cutting-edge methods and theoretical shifts that empower today’s archaeologists to reconstruct the intricate narratives of our ancestors.

8. **Augustus Pitt Rivers: The Pioneer of Scientific Excavation and Typology**Building upon the early methodical approaches, Augustus Pitt Rivers emerged as a transformative figure in the late 19th century, profoundly shaping archaeology into a rigorous scientific discipline. As an army officer and ethnologist, he brought an unparalleled discipline to his excavations on his English estates in the 1880s. His standards were highly methodical for the era, earning him widespread recognition as the first scientific archaeologist, meticulously documenting every aspect of his findings.

Pitt Rivers’ most significant methodological innovation was his unwavering insistence that all artifacts, not just the aesthetically pleasing or unique ones, be carefully collected and cataloged. He revolutionized the approach to material culture by arranging artifacts according to type, or “Typology (archaeology),” and then chronologically within those types. This systematic arrangement was designed specifically to highlight the evolutionary trends in human artifacts, allowing for a far more accurate dating of objects and a deeper comprehension of technological and cultural progression.

His approach underscored the principle that every piece of evidence, no matter how small or seemingly insignificant, held a vital clue to the past. By moving beyond mere treasure hunting to a comprehensive collection and analysis of even the most mundane items, Pitt Rivers established a precedent for data collection that remains fundamental to modern archaeological practice, truly transforming the field into a science dedicated to understanding past lifeways through the entire material record.

9. **Sir Mortimer Wheeler and Kathleen Kenyon: The Grid System and Modern Fieldwork**The intellectual lineage of archaeological method continued to advance swiftly in the early 20th century with the contributions of Sir Mortimer Wheeler. His highly disciplined approach to excavation, particularly during the 1920s and 1930s, marked another significant leap forward in bringing scientific rigor to the field. Wheeler’s commitment to systematic coverage on his digs ensured that sites were not merely plundered for spectacular finds, but thoroughly investigated and recorded.

One of Wheeler’s most enduring innovations was the development of the “grid system” of excavation. This method involved dividing a site into a series of squares, with balks (unexcavated sections of earth) left between them. These balks provided crucial stratigraphic profiles, allowing archaeologists to observe and record the layers of soil and their contents in three dimensions, maintaining essential contextual information. This highly structured approach was further refined and improved by his student, Kathleen Kenyon, who applied it extensively in her own influential excavations.

This era also witnessed the professionalization of archaeology, moving it from the domain of enthusiastic amateurs to a recognized academic discipline. Universities and even schools began offering archaeology as a subject, leading to a new generation of trained professionals. By the end of the 20th century, a vast majority of archaeologists, especially in developed countries, were university graduates, equipped with sophisticated methodologies. This period also saw the increasing prevalence of specialized sub-disciplines like maritime archaeology, which explores submerged sites, urban archaeology, focusing on cities, and rescue archaeology, which developed in response to the rapid pace of commercial development threatening ancient sites.

10. **Evolution of Archaeological Theory: From Cultural-Historical to Processualism and Beyond**The theoretical underpinnings of archaeology are as dynamic and layered as the sites it investigates, with no single, universally adhered-to approach. When the discipline first solidified in the late 19th century, the dominant theoretical framework was cultural-historical archaeology. Its primary goal was not just to document *that* cultures changed but to explain *why* these transformations occurred, emphasizing historical particularism and tracing cultural developments. Alongside this, the direct historical approach was utilized by many archaeologists studying past societies with clear, continuing links to existing indigenous groups, allowing for comparisons between ancient and contemporary ethnic and cultural practices.

The 1960s ushered in a significant paradigm shift with the emergence of “New Archaeology,” largely spearheaded by American archaeologists like Lewis Binford and Kent Flannery. This movement rebelled against the descriptive nature of cultural-historical archaeology, advocating for a more “scientific” and “anthropological” approach. Processual archaeology, as it became known, placed immense importance on hypothesis testing, explicit research designs, and the rigorous application of the scientific method to generate universal laws of cultural change, seeking to explain human behavior rather than just describe it.

However, the 1980s saw the rise of a new postmodern movement: post-processual archaeology. British archaeologists such as Michael Shanks, Christopher Tilley, Daniel Miller, and Ian Hodder led this critique, challenging processualism’s claims of scientific positivism and impartiality. Post-processualism emphasized the importance of self-critical theoretical reflexivity, recognizing the subjective nature of interpretation and the influence of the archaeologist’s own background on their understanding of the past. This approach brought to the forefront issues of power, identity, and agency within ancient societies.

The debate between processualism and post-processualism continues to shape the discipline, with each challenging the other’s validity. Amidst this ongoing intellectual discourse, another theory, historical processualism, has emerged, seeking to synthesize the strengths of both, incorporating processualism’s focus on cultural processes with post-processualism’s emphasis on reflexivity and historical context. Modern archaeological theory now draws from a vast array of influences, including systems theory, neo-evolutionary thought, phenomenology, cognitive science, structural functionalism, Marxism, gender-based and feminist archaeology, queer theory, postcolonial thoughts, materiality, and posthumanism, creating a rich and complex intellectual landscape.

11. **Remote Sensing: Unveiling Buried Worlds from Afar**Before a single spade touches the earth, modern archaeology often begins with remote sensing, a powerful suite of non-invasive technologies designed to locate sites within vast areas or provide detailed information about known sites and regions from a distance. These instruments, classified as either passive or active, allow archaeologists to peer beneath the surface, revealing hidden patterns and structures without disturbing the delicate archaeological record.

Passive instruments, like satellite imagery, detect natural energy reflected or emitted from the observed scene. They sense radiation that objects either emit themselves or reflect from a natural source. In contrast, active instruments emit their own energy and then record what is reflected back, providing a dynamic way to probe the subsurface. Among these, Light Detection and Ranging (Lidar) stands out as a revolutionary tool.

Lidar operates by transmitting a light pulse from a laser and then measuring the backscattered or reflected light with sensitive detectors. The distance to an object is precisely determined by calculating the time taken for the light to travel to the object and return, using the known speed of light. Lidars can generate highly accurate topographical maps, revealing subtle changes in the landscape that might indicate buried structures, ancient roads, or past agricultural systems. When integrated into a laser altimeter, Lidar can measure the instrument platform’s height above the surface, and by knowing the platform’s height relative to the Earth, the underlying topography can be accurately mapped.

Another increasingly vital tool in the remote sensing arsenal is the drone. Archaeologists worldwide are leveraging small, cost-effective drones, some costing as little as £650, to dramatically speed up survey work and help protect vulnerable sites from encroachment by squatters, builders, and miners. In Peru, for instance, drones have enabled researchers to rapidly produce intricate three-dimensional models of archaeological sites in mere days or weeks, a task that traditionally took months or even years with conventional methods. These aerial platforms can capture images at varying altitudes, offering unparalleled perspectives; as Jeffrey Quilter, an archaeologist with Harvard University, noted, “You can go up three metres and photograph a room, 300 metres and photograph a site, or you can go up 3,000 metres and photograph the entire valley.” In a notable application, drones weighing about 5 kg were employed in September 2014 for 3D mapping of the above-ground ruins of the Greek city of Aphrodisias, with the resulting data currently undergoing analysis by the Austrian Archaeological Institute in Vienna. Although drones have presented altitude challenges in high-altitude regions like the Andes, plans are underway to develop drone blimps using open-source software to overcome these limitations.

12. **Field Survey: Systematically Locating and Mapping Our Human Heritage**The archaeological project, after or sometimes in lieu of remote sensing, often progresses to a meticulous field survey, a critical phase for systematically locating and understanding both previously unknown sites and features within known sites. Regional survey aims to discover new archaeological locations across a broad area, while site survey focuses on pinpointing specific features of interest, such as ancient houses, middens, or burial grounds, within a defined site boundary. These two goals frequently employ similar methodologies, providing comprehensive coverage of the landscape.

In the nascent days of archaeology, extensive survey was not widely practiced; cultural historians and early researchers often relied on local knowledge to find monumental sites and focused their efforts on excavating only clearly visible features. The significance of systematic regional settlement pattern survey was truly pioneered by Gordon Willey in 1949 in the Viru Valley of coastal Peru. His innovative approach, and the subsequent rise of processual archaeology, elevated survey work to a prominent position, recognizing its indispensable value in understanding broader human settlement patterns and societal structures.

Field survey offers numerous compelling benefits, especially when conducted as a preliminary step or even as an alternative to excavation. It is notably less time-consuming and expensive than full-scale excavation, as it avoids the labor-intensive process of processing large volumes of soil to retrieve artifacts, although surveying extensive regions can still incur significant costs, often necessitating the use of sampling methods. Crucially, survey represents a non-destructive form of archaeology, circumventing the ethical concerns—particularly those important to descendant communities—associated with physically altering or destroying a site through excavation. Moreover, it is the sole method for acquiring certain types of information, such as regional settlement patterns and the spatial organization of settlements. The data gathered from surveys are commonly translated into detailed maps, which visually represent surface features and the distribution of artifacts across the landscape.

The most straightforward survey technique is surface survey, which involves methodically traversing an area, typically on foot, but sometimes utilizing mechanized transport, to search for any features or artifacts visible on the ground. While effective for surface-level discoveries, this technique has limitations, as it cannot detect sites or features completely buried beneath the earth or obscured by dense vegetation. Surface survey may also incorporate mini-excavation techniques, such as augers, corers, and shovel test pits, to quickly ascertain subsurface conditions. If no materials are found, the surveyed area is typically deemed archaeologically sterile.

Advancing beyond ground-level observations, aerial survey employs cameras mounted on airplanes, balloons, Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), or even kites, to capture a bird’s-eye view. This elevated perspective is invaluable for rapidly mapping large or intricate sites and for documenting the status of ongoing archaeological digs. Aerial imaging possesses the remarkable ability to detect numerous features that are entirely invisible from the ground. For instance, plants growing above a buried human-made structure, like a stone wall, may exhibit stunted growth due to reduced soil depth, while those above features like middens (ancient refuse heaps) may grow more vigorously due to enriched soil. Photographs of ripening grain, which undergoes rapid color changes at maturation, have precisely revealed the outlines of buried structures. Furthermore, aerial photographs taken at different times of the day can highlight structural outlines through variations in shadows. Modern aerial survey also integrates advanced technologies like ultraviolet, infrared, ground-penetrating radar wavelengths, Lidar, and thermography to provide a multi-spectral view of the hidden past.

Geophysical survey offers arguably the most effective means to visualize what lies beneath the ground without excavation. Magnetometers, for example, detect minute deviations in the Earth’s magnetic field, which can be caused by the presence of iron artifacts, ancient kilns, certain types of stone structures, and even less obvious features like ditches and middens. Similarly, devices that measure the electrical resistivity of the soil are widely deployed. Archaeological features with electrical resistivity values that contrast with the surrounding natural soils can be accurately detected and mapped; some features, such as those constructed from stone or brick, typically exhibit higher resistivity, while others, like organic deposits or unfired clay, tend to have lower resistivity. Although the use of metal detectors has sometimes been equated with treasure hunting, many archaeologists now recognize them as effective tools in formal archaeological surveying, used in contexts like analyzing musketball distribution on battlefields or locating service cables prior to excavation. In the UK, metal detectorists have been encouraged to contribute to archaeology through schemes like the Portable Antiquities Scheme, provided they meticulously record their finds and refrain from removing artifacts from their archaeological context. For underwater archaeology, regional surveys utilize specialized geophysical or remote sensing devices such as marine magnetometers, side-scan sonar, or sub-bottom sonar to map submerged landscapes.

13. **The Art and Science of Excavation: Unearthing Context and Chronology**While remote sensing and field surveys provide crucial preliminary data, archaeological excavation remains the primary source of the majority of information recovered in most field projects. It is through careful digging that archaeologists can unveil several critical types of information generally inaccessible through other methods, including stratigraphy—the layered history of a site—its three-dimensional structural relationships, and, most importantly, verifiably primary context, meaning artifacts found precisely where they were left by their ancient users.

Modern excavation techniques are defined by an unyielding demand for precision. The exact locations of all objects and features—their provenance or provenience—must be meticulously recorded. This invariably involves determining their horizontal coordinates and, in many cases, their vertical position within the stratigraphic sequence. Equally vital is documenting their association, or their spatial and chronological relationship with nearby objects and features. This rigorous recording allows archaeologists in the post-excavation phase to deduce which artifacts and features were likely utilized together and which may belong to distinct phases of activity or different cultural occupations. For example, careful excavation often reveals a site’s stratigraphy, illustrating that if a location was inhabited by a succession of different cultures, artifacts from more recent periods will consistently be found above those from more ancient ones.

It is important to acknowledge that excavation is, in relative terms, the most expensive phase of archaeological research. Furthermore, as a fundamentally destructive process—since once a layer is removed, it cannot be perfectly recreated—it carries significant ethical implications. Consequently, very few archaeological sites are ever excavated in their entirety. The precise percentage of a site that is excavated often depends greatly on the regulations of the country and the specific “method statement” issued for the project. Therefore, sampling strategies become even more crucial in excavation than they are in survey work.

Initially, large mechanical equipment, such as backhoes or JCBs, may be employed to remove the overlying topsoil, known as overburden, particularly in areas where recent disturbances are evident and deep cultural layers are anticipated. However, this method is increasingly used with extreme caution to avoid damaging underlying archaeological remains. Following this initial dramatic step, the newly exposed area is typically hand-cleaned with smaller tools like trowels or hoes, ensuring that all subtle archaeological features, such as post-holes, ditches, or remnants of walls, become clearly apparent.

The next crucial task is to develop a comprehensive site plan, which then guides the chosen method of excavation. Features that have been dug into the natural subsoil, such as pits, post-holes, or ditches, are normally excavated in carefully controlled portions. This process deliberately leaves a visible archaeological section—a vertical slice through the feature and surrounding soil—which is then meticulously drawn and photographed for permanent recording. Each feature is composed of two primary elements: the “cut,” which describes the original edge or boundary where the feature was initially dug into the natural soil, and the “fill,” which is the material that subsequently accumulated within the feature, often appearing distinctly different from the natural surrounding soil. Both the cut and the fill are assigned consecutive numbers for recording purposes. Scaled plans and sections of these individual features are drawn directly on site, accompanied by both black and white and color photographs, and detailed recording sheets are filled in, describing the context of each. All this diligently gathered information serves as the permanent record of the now-destroyed archaeology and is indispensable for the subsequent description and interpretation of the site, forming the bedrock of archaeological knowledge.

14. **Post-Excavation Analysis: Decoding the Material Record**Once the intricate process of excavation is complete, or artifacts have been systematically collected from surface surveys, the crucial and often most time-consuming phase of an archaeological investigation begins: post-excavation analysis. It is during this period that the raw data unearthed from the earth is transformed into meaningful insights about past human societies. It is not uncommon for the final reports of major excavations, detailing years of fieldwork, to take many additional years to be meticulously prepared and published.

At a fundamental level, the analysis involves several critical steps: retrieved artifacts are carefully cleaned, catalogued with unique identifiers, and then systematically compared to published collections from other sites. This comparative process frequently includes classifying them typologically—grouping them by shared forms and functions—and identifying other sites that exhibit similar artifact assemblages. Such comparisons help establish broader cultural connections and chronological relationships across regions, allowing archaeologists to build a mosaic of past human interactions and technological diffusion.

Beyond basic classification, modern archaeological science provides a far more comprehensive range of analytical techniques to extract maximum information from every find. These advanced scientific methods allow artifacts to be precisely dated using various absolute and relative dating techniques, and their compositions can be thoroughly examined through material analysis, revealing insights into ancient manufacturing processes, trade networks, and resource utilization. For example, identifying the geological source of a specific stone tool or pottery type can illuminate ancient exchange systems that spanned vast distances.

Furthermore, the biological and environmental remains collected from a site yield invaluable data. Bones, whether human or animal, are analyzed using zooarchaeology to understand ancient diets, hunting practices, animal domestication, and environmental conditions. Plant remains provide insights into ancient agriculture, wild resource use, and botanical environments through paleoethnobotany. Pollen analysis, or palynology, reconstructs past vegetation and climate, offering a backdrop against which human activities unfolded. Stable isotope analysis of human and animal remains can reveal dietary patterns and geographic origins, tracing movements and life histories. When texts are recovered, they are meticulously deciphered and translated, providing direct written accounts that complement and sometimes contradict the material evidence, offering a more nuanced understanding of complex societies.

These diverse scientific and interpretive techniques frequently provide information that would simply not be discernible through excavation alone. They enable archaeologists to move beyond simply describing what was found to explaining *how* and *why* ancient societies functioned, contributing profoundly to our understanding of a site’s inhabitants, their daily lives, their beliefs, and their incredible organizational and technical capabilities, much like those that constructed the enduring monuments of Egypt.

15. **The Diverse Tapestry of Archaeology: Subfields and its Enduring Purpose**As with many extensive academic disciplines, archaeology is a rich tapestry woven from a vast number of specialized sub-disciplines, each characterized by a distinct method, type of material, geographical or chronological focus, or thematic concern. These specializations allow archaeologists to develop deep expertise, whether in the analysis of lithic tools (lithic analysis), the study of ancient music, or the reconstruction of past environments through archaeobotany. Geographical and chronological foci give rise to fields like Near Eastern archaeology, Islamic archaeology, or Medieval archaeology, each grappling with the unique challenges and vast histories of their respective regions and time periods. Thematic concerns, on the other hand, birth fields such as maritime archaeology, which explores shipwrecks and submerged landscapes, landscape archaeology, battlefield archaeology, or the archaeology of specific cultures and civilizations like Egyptology, Indology, and Sinology.

One particularly illuminating sub-discipline is historical archaeology, which focuses on the study of cultures that possessed some form of writing, and thus deals with objects and issues from documented periods of the past. This field provides a critical complement to historical texts. For example, in medieval Europe, archaeologists have delved into the illicit burial practices of unbaptized children, studying both medieval texts and excavated cemeteries to reconstruct long-forgotten social attitudes and religious practices. In downtown New York City, archaeologists have exhumed the 18th-century remains of the African Burial Ground, providing a powerful material record of enslaved peoples whose stories were largely absent or distorted in written histories. Similarly, during the destruction of remnants of the WWII Siegfried Line, emergency archaeological digs were conducted to further scientific knowledge, revealing crucial details about the line’s construction and the lives of those who built and defended it.

Ethnoarchaeology represents another vital sub-discipline, involving the ethnographic study of living people. Its primary design is to create analogies and provide a framework for interpreting the archaeological record. This approach gained significant prominence during the processual movement of the 1960s and remains a vibrant component of both post-processual and other current archaeological approaches. Early ethnoarchaeological research often focused on hunter-gatherer or foraging societies, observing their material culture production, use, and discard patterns to inform interpretations of prehistoric sites. Today, however, ethnoarchaeological research has expanded significantly to encompass a much wider array of human behaviors and societal structures across diverse cultures.

Experimental archaeology, another fascinating sub-discipline, involves the application of controlled experiments to explore and test hypotheses about past human behaviors and technologies. This hands-on approach might involve reconstructing ancient tools, building replica structures, or recreating ancient crafts to understand the skills, resources, and time required for past activities. Such experiments provide unique insights into the practicalities of ancient life and the capabilities of past peoples, for instance, shedding light on the immense organizational and technical prowess required to construct monumental structures like the Great Pyramids.

At its core, the overarching purpose of archaeology is to illuminate past societies and the grand development of the human race. Crucially, over 99% of humanity’s development unfolded within prehistoric cultures, societies that, by definition, did not utilize writing. Without written records, archaeology offers the sole means to understand these vast periods of human history. It stretches back approximately 2.5 million years to the discovery of the first stone tools—the Oldowan Industry—providing insights into momentous developments such as the evolution of humanity during the Paleolithic period, when hominins progressed from australopithecines in Africa to modern Homo sapiens. Archaeology is indispensable for understanding humanity’s technological advances, including the mastery of fire, the progressive refinement of stone tools, the discovery of metallurgy, the nascent stirrings of religion, and the advent of agriculture. Without archaeological investigation, precious little would be known about the material culture of humanity that predates written communication.

Moreover, archaeology is not confined to the study of prehistoric, pre-literate cultures; it equally enriches our understanding of historical, literate societies through the sub-discipline of historical archaeology. For many ancient literate cultures, such as Ancient Greece and Mesopotamia, surviving written records are frequently incomplete and often carry inherent biases. Literacy in these societies was often restricted to elite classes—clergy or court/temple bureaucracy—whose interests and worldviews often diverged significantly from those of the general populace. Writings produced by more representative segments of the population were far less likely to be preserved for posterity. Consequently, written records tend to reflect the biases, assumptions, cultural values, and potential deceptions of a limited range of individuals, representing only a fraction of the broader population. The material record, in contrast, may offer a more equitable representation of society, though it too is subject to its own biases, such as sampling bias and differential preservation, emphasizing the need for a balanced approach.

Indeed, archaeology often provides the only means by which we can learn about the existence and behaviors of peoples long past. Across millennia, thousands of cultures, societies, and billions of individuals have lived and disappeared, leaving little to no written record, or their existing records are misrepresentative or incomplete. Writing, as we know it today, only emerged in human civilization in the 4th millennium BC, and even then, in a relatively small number of technologically advanced civilizations. In stark contrast, Homo sapiens has existed for at least 200,000 years, with other Homo species preceding us by millions. These literate civilizations, perhaps not coincidentally, are the best-known, having been accessible to historians for centuries, while the profound study of pre-historic cultures has only recently blossomed into a scientific endeavor. Even within literate civilizations, countless events and crucial human practices may have never been officially recorded. Any knowledge of the early years of human civilization—the development of agriculture, the cult practices of folk religion, or the rise of the first cities—must predominantly come from the meticulous work of archaeology.

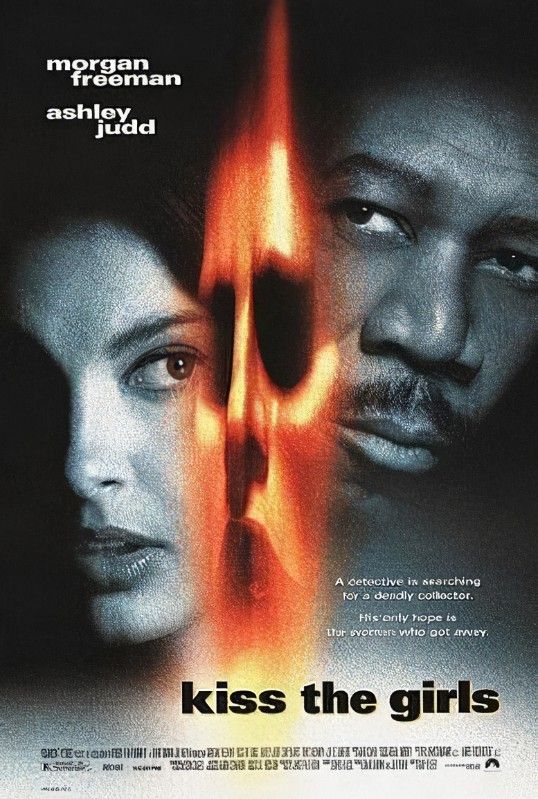

Beyond their undeniable scientific importance, archaeological remains frequently possess profound political or cultural significance for the descendants of the people who created them, monetary value for collectors, or compelling aesthetic appeal. It is this broader appeal that sometimes leads the public to identify archaeology with the recovery of such aesthetic, religious, political, or economic “treasures,” rather than with the diligent reconstruction of past societies. While captivating in popular fiction, such as cinematic adventures like *Raiders of the Lost Ark*, *The Mummy*, or *King Solomon’s Mines*, these endeavors are rarely representative of modern archaeology’s rigorous scientific and ethical standards. Nevertheless, the enduring fascination with ancient wonders, like the Great Pyramids, continues to fuel our collective quest to understand the astounding achievements of our ancient forebears.