For centuries, the name “Philistine” has evoked images of formidable adversaries, largely shaped by the ancient texts of the Hebrew Bible. To gain a comprehensive understanding of this ancient people who inhabited the southern coast of Canaan during the Iron Age, it is essential to move beyond conventional narratives and examine the extensive historical records, archaeological findings, and linguistic evidence that collectively reveal a far more intricate and compelling portrayal of their existence. Their history is characterized by migration, adaptation, conflict, and a puzzling disappearance, leaving a legacy that continues to captivate scholars and historians.

This exploration will carefully analyze the diverse pieces of evidence that illuminate the true nature of the Philistines. From their possible origins in the Aegean region to their flourishing city-states and complex relationships with neighboring cultures, the investigation will uncover the defining features of their unique culture and their enduring impact on the ancient world. This study is not merely a recounting of conflicts; it is an inquiry into identity, resilience, and an effort to provide a voice to a people frequently portrayed solely through the lens of biblical confrontations.

Origins and Identity of the Philistine Confederation

The Philistines were a distinct ancient people who established themselves on the south coast of Canaan during the pivotal Iron Age. They formed a powerful confederation of city-states, a region that came to be known as Philistia. This confederation was a significant power in the ancient Levant, engaging with various neighboring societies, including the Israelites.

Their name itself carries historical weight, derived from the Hebrew Pəlištī (פְּלִשְׁתִּי; plural Pəlištīm, פְּלִשְׁתִּים), meaning ‘people of Pəlešeṯ’. Cognates of this name also appear in ancient records, such as Akkadian Palastu and Egyptian Palusata, underscoring their widespread recognition in the ancient world. While their exact native endonym remains unknown, these historical records affirm their distinct identity within the broader tapestry of Iron Age societies.

Origins and Migration: Linking the Philistines to the Sea Peoples

Compelling evidence suggests that the Philistines originated from a Greek immigrant group hailing from the Aegean region. This group settled in Canaan around 1175 BC, a tumultuous period often referred to as the Late Bronze Age collapse. Over generations, these immigrants intermixed with the indigenous Canaanite societies, absorbing local elements while remarkably preserving many aspects of their own unique culture, creating a fascinating blend.

The Philistines are widely identified with one of the enigmatic confederations of seafarers known as the Sea Peoples. These groups are recorded as having attacked ancient Egypt and other Eastern Mediterranean civilizations during the Late Bronze Age collapse. While their exact origins are still debated and likely diverse, it is generally agreed that the Sea Peoples had roots in the broader Southern European and West Asian areas, including western Asia Minor, the Aegean, and the islands of the East Mediterranean.

Egyptian sources specifically name one of these implicated Sea Peoples as the Peleset (pwrꜣsꜣtj), which scholars widely accept as cognate with the Hebrew Peleshet and the parallel Assyrian term Palastu. Following their defeat at the hands of Pharaoh Ramesses III at the Battle of the Delta around 1175 BC, Egyptian inscriptions from his funerary temple in Medinet Habu and the Great Harris Papyrus allege that he relocated a number of these Peleset to southern Canaan. This account, coupled with the linguistic link and the presumed Aegean origins of the Sea Peoples, has strongly led many scholars to identify the Peleset with the biblical Philistines, suggesting a significant migration event played a role in their establishment in Canaan.

Linguistic Journey of the Name ‘Philistine’

The very term “Philistine” has a rich linguistic history, traveling through various ancient languages before arriving in English. Its journey begins with the Hebrew Pəlištī (פְּלִשְׁתִּי), which, in its plural form Pəlištīm (פְּלִשְׁתִּים), directly translates to ‘people of Pəlešeṯ’. This Hebrew root points to a geographical connection, highlighting their identity as inhabitants of a specific land.

Tracing its path further, the English term is derived from Old French Philistin, which itself came from Classical Latin Philistinus, and then from Late Greek Philistinoi, ultimately from Koine Greek Φυλιστιειμ (Philistiim). This linguistic progression showcases how their name transcended cultural boundaries in the ancient world. Interestingly, cognates also appear in Akkadian as Palastu and in Egyptian as Palusata, reinforcing the idea that these people were known by similar designations across different influential empires of the time. The native Philistine endonym, however, remains a mystery, adding to the intrigue of their ancient identity.

Philistine Pentapolis and the Nature of Their Settlement in the Southern Levant

By Iron Age II, the Philistines had solidified their presence in the southern Levant, forming a powerful ethnic state centered around a confederation of five key city-states, famously known as the Philistine Pentapolis. These formidable cities were Gaza, Ashdod, Ashkelon, Ekron, and Gath. Their territory stretched from Wadi Gaza in the south to the Yarqon River in the north, though their eastern border remained fluid and undefined, often encroaching upon neighboring lands.

Archaeological investigations have provided fascinating insights into the establishment of these cities. While the Sea Peoples are often associated with widespread destruction, cities that would become the core of Philistine territory, such as Ashdod, Ashkelon, Gath, and Ekron, show strikingly few signs of an intervening event marked by destruction during the Late Bronze Age collapse. In some instances, like Aphek, an Egyptian garrison was destroyed, but this was followed by a local Canaanite phase before the peaceful introduction of Philistine pottery. This suggests that the Philistines might not have forcefully injected themselves into every part of the southern Levant, and their presence in these core cities may have involved a more gradual cultural integration or peaceful settlement, challenging some earlier assumptions about their arrival.

The Biblical Portrayal of the Philistines and Their Conflicts with Israel

The Hebrew Bible serves as the primary and most extensive source of information about the Philistines, particularly detailing their frequent and often intense conflicts with the peoples of the region, most notably the Israelites. Within these biblical accounts, the Philistines are consistently depicted as formidable adversaries, presenting a serious and recurring threat to the nascent Israelite kingdoms.

Their narrative in the Bible often highlights a period of significant Philistine dominance, especially during the time of the Judges and allegedly during the reigns of Saul and Samuel. They are portrayed as powerful foes who, at one point, even held lordship over Israel, going so far as to forbid the Israelites from possessing iron implements of war, a strategic move to maintain their military superiority. However, the biblical chronicles ultimately depict their subjugation by King David, marking a turning point in the Israelite-Philistine relationship. It is important to note that the exact accuracy and historical interpretation of these narratives remain subjects of ongoing academic debate among scholars.

Reevaluating the Philistines in the Torah: A Narrative of Coexistence and Diplomacy

The portrayal of the Philistines in the Torah, or the Pentateuch, significantly differs from their depiction in later biblical texts. Notably, the Torah does not include the Philistines among the nations Abraham’s descendants were destined to displace from Canaan. Furthermore, although the land they inhabited falls within the geographic boundaries described, the Philistines are absent from the list of nations Moses instructs the Israelites to conquer.

The Torah instead presents examples of peaceful coexistence and diplomatic relations. Genesis 21:22–27 describes Abraham entering into a covenant of kindness with Abimelech, the Philistine king, and his descendants. Likewise, Abraham’s son Isaac establishes a treaty with the Philistine king in Genesis 26, illustrating periods of diplomatic engagement rather than open hostility. Additionally, according to Exodus 13:17, God directs the Israelites to avoid the Philistines during their Exodus from Egypt, implying a strategy of avoidance rather than immediate conflict. A notable linguistic detail is that, unlike most other ethnic groups in the Torah, the Philistines are almost always referred to without the definite article, suggesting a distinctive understanding or relationship with them during this earlier period.

Philistines in Deuteronomistic History: From Fierce Adversaries to Complex Interactions

The depiction of the Philistines undergoes a marked transformation in the Deuteronomistic history, which includes the books from Joshua to 2 Kings. Rabbinic traditions and the authors of the Septuagint—the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible—distinguish between the Philistines mentioned in Genesis and those portrayed in these later historical narratives. For example, the Septuagint often translates “Philistines” as “foreigners” (ἀλλόφυλοι) in the Books of Judges and Samuel, implying a broader sense of “non-Israelite inhabitants of the Promised Land” during this period.

This era is defined by prolonged and intense conflict between the Philistines and the Israelites. Judges 13:1 notes Philistine dominance over Israel during the time of Samson, who famously defeated and killed over a thousand Philistines. One of the most notable events is recorded in 1 Samuel 5, where the Philistines capture the sacred Ark of the Covenant, holding it for several months before its miraculous return to the Israelites at Beth Shemesh, as recounted in 1 Samuel 6.

The Deuteronomistic history consistently portrays the Philistines as principal enemies of Israel, appearing more than 250 times and ultimately being subdued by King David. Despite this adversarial depiction, relationships were nuanced. The Cherethites and Pelethites, groups believed to have Philistine origins, notably served as King David’s trusted bodyguards and soldiers, revealing complexities beyond mere hostility. Their eventual fate was to succumb to emerging regional powers, falling under the dominion of the Neo-Babylonian and later the Achaemenid Empires, resulting in their disappearance as a distinct ethnic entity by the late fifth century BCE.

Prophetic Perspectives on the Philistines: Divine Judgment and Ancestral Origins

While the historical books of the Hebrew Bible offer a narrative of conflict and eventual subjugation, the prophetic books provide a different lens through which to view the Philistines, often focusing on their ultimate fate and their place in divine plans. These later accounts frequently speak of the destruction of the Philistines, signaling a coming end to their distinct identity and power in the region. Their mentions in these texts serve as prophetic warnings or pronouncements of judgment against nations.

For instance, the prophet Amos, in chapter 1, verse 8, places the Philistines at Ashdod and Ekron, suggesting their continued presence and significance at the time of his prophecies. More strikingly, Amos 9:7 records a profound statement from God: that just as He brought Israel from Egypt, He also brought the Philistines from Caphtor, a geographical region often identified with Crete or Minoan civilization. This reinforces the long-standing theory of their Aegean origins, even within the biblical framework, offering a unique theological perspective on their migration and settlement. Jeremiah 47:4 further describes the Philistines as the “remnant of the Caphtorim,” hinting at the mysterious destruction of the Caphtorim themselves, whether by divine or human means, and establishing a clear link between the Philistines and this ancestral homeland.

Enduring Conflicts: The Military Struggles Between Israelites and Philistines

The conflicts between the Israelites and the Philistines are a recurring theme throughout the Hebrew Bible, shaping the early history of the Israelite kingdoms and cementing the Philistines’ image as formidable adversaries. These battles were not merely isolated skirmishes but prolonged struggles for dominance and control over the strategic Levant. From minor engagements to pivotal clashes, these encounters highlight the military prowess of both sides.

One significant instance is the Battle of Aphek, where the Israelites suffered a devastating defeat, leading to the capture of the sacred Ark of the Covenant, as detailed in 1 Samuel 5. This event underscores the Philistines’ power and their ability to inflict profound spiritual and military blows upon their enemies. The biblical narrative also records a period when the Philistines subjected the Israelites to a localized disarmament regime, as 1 Samuel 13:19-21 states that no Israelite blacksmiths were permitted, forcing them to seek Philistine assistance for sharpening their weapons and agricultural implements, a clear strategy to maintain military superiority. Iconic tales like David’s single combat victory over Goliath near the Valley of Elah symbolize the turning point in this long-standing rivalry, leading to a shift in power dynamics. However, Philistine military success was not always countered, as evidenced by their victory over the Israelites on Mount Gilboa, which resulted in the tragic deaths of King Saul and his three sons, Jonathan, Abinadab, and Malkishua.

Tracing the Peleset: Egyptian Records and the Historical Footprint of the Philistines

The Medinet Habu reliefs of Ramesses III provide the earliest and most direct Egyptian reference to the Peleset, widely believed to represent the Philistines. However, their presence is not confined to this singular depiction. Inscriptions from the New Kingdom period offer additional, though often fragmented, insights into the Peleset and their activities between approximately 1150 BCE and 900 BCE. These texts complement and expand upon the biblical narrative, offering an external and contemporaneous perspective on their origins and movements.

The Peleset are mentioned in four key Egyptian sources from this period. In addition to the renowned Medinet Habu inscriptions, which portray a coalition of Sea Peoples, including the Peleset, defeated by Ramesses III, the Rhetorical Stela at Deir el-Medina is of particular significance. It references the Peleset alongside the Teresh, describing them as sailing “in the midst of the sea,” indicating a maritime culture and possibly suggesting a shared Anatolian origin.

The Great Harris Papyrus I, discovered in a tomb at Medinet Habu, recounts Ramesses III’s military campaigns against the Sea Peoples, declaring that the Peleset were “reduced to ashes” and subsequently brought to Egypt as captives and settled in garrisoned fortresses. This account may imply a temporary settlement in Egypt prior to their migration into Canaan, or a strategic relocation by Ramesses III, possibly as military colonists or mercenaries in the Levant.

The Onomasticon of Amenope, dated to the late twelfth or early eleventh century BCE, provides the most direct connection between the Peleset and the Philistine Pentapolis. It lists cities such as Ashkelon, Ashdod, and Gaza—key Philistine urban centers—alongside the Peleset, as well as other Sea Peoples including the Sherden and Tjekker. This textual evidence supports a geographic and political link between the Peleset and the core Philistine cities, suggesting that various Sea Peoples may have contributed to the formation or occupation of these sites.

Aegean Echoes in Canaan: Archaeological Evidence of Philistine Origins and Cultural Integration

Archaeological excavations across the Philistine Pentapolis and adjacent regions have revealed a distinctive material culture that offers critical insight into the Philistines’ origins and their cultural evolution. Notably, evidence from pottery and architecture points to a significant migration from the Aegean world, likely originating in Anatolia and Cyprus, during the twelfth century BCE. These findings reinforce long-standing theories of the Philistines’ foreign origin.

Philistine ceramic traditions, in particular, serve as vital indicators of cultural heritage. Early Philistine pottery closely resembles Mycenaean Late Helladic IIIC ware, identifiable by its brown and black painted motifs. This style later developed into Philistine Bichrome ware during Iron Age I, marked by black and red geometric or figural designs on a white slip surface. The progression of these ceramic styles indicates both continuity and local adaptation.

Architectural discoveries also support an Aegean connection. At Ekron, a large structure measuring approximately 240 square meters was uncovered, featuring thick walls, a wide entrance leading into a central hall with a circular pebble-paved hearth, and stone benches along the walls. This configuration aligns closely with the Mycenaean megaron-style hall. Additionally, three small bronze wheels found within the site resemble cultic stand components used in the Aegean, suggesting a ritualistic function. An inscription from Ekron referencing the term “PYGN” or “PYTN” has been tentatively linked to “Potnia,” a Mycenaean goddess, further supporting this interpretation.

Faunal remains offer additional cultural context. Butchered dog and pig bones found at Ashkelon, Ekron, and Gath suggest dietary practices distinct from those of the local Canaanite populations, where such animals were typically avoided. Moreover, the presence of wineries and loom weights similar to those found at Mycenaean sites underscores the persistence of Aegean lifestyle elements among early Philistine communities.

While certain features reflect interaction with or adaptation to Canaanite culture—possibly through assimilation or technological exchange—the broader archaeological and genetic evidence strongly supports the theory that the initial Philistine settlers arrived with a coherent Aegean cultural identity. Over time, this identity evolved as it blended with local traditions, shaping a unique cultural footprint in the southern Levant.

Unearthing Identity: Ashkelon Cemetery and the Genetic Legacy of the Philistines

For many years, direct archaeological evidence of Philistine burial customs remained absent, deepening the enigma surrounding their distinct cultural identity. This changed in 2016 with the discovery of a large Philistine cemetery near Ashkelon, which offered unprecedented insight into their mortuary practices and genetic origins. The cemetery, uncovered through a thirty-year investigation led by the Leon Levy Expedition, contained the remains of more than 150 individuals interred in oval-shaped graves. These findings provided a rare opportunity to examine the physical remnants of this elusive ancient population.

The most significant outcome of this discovery emerged through a 2019 genetic study that analyzed DNA extracted from the Ashkelon remains. Researchers found that while all three Ashkelon populations—early Iron Age, later Iron Age, and modern—shared the majority of their ancestry with the indigenous Semitic-speaking Levantine populations, the early Iron Age group exhibited a notable genetic distinction. This group, representing the earliest Philistine settlers, displayed clear markers of “European-related admixture,” indicating a significant gene flow from a European-related population during the transition from the Bronze to the Iron Age.

This genetic signal, however, disappeared in the later Iron Age population, suggesting a rapid assimilation process with the local population over several generations. Although the precise European origin could not be conclusively identified due to limitations in the available ancient genomes, the Philistine DNA showed affinities with ancient populations from Crete and the Iberian Peninsula, as well as genetic similarities with modern Sardinians. These findings strongly support the long-standing hypothesis of a migration from the Aegean region, now reinforced not only by material culture and historical accounts but also by biological evidence.

Philistine or Palistin? Reexamining the Northern Connection and the Debate on Origins

The identity of the Philistines, particularly their origins and the question of whether they constituted a unified ethnic group, continues to generate active scholarly discussion. Recent archaeological and linguistic discoveries have further complicated the debate, introducing new possibilities and challenging older assumptions. One compelling line of inquiry centers on a potential connection between the biblical Philistines and a kingdom named Palistin, referenced in Luwian inscriptions from northern Syria. Though the term also appears as Walistina in some texts, this variation may reflect dialectal differences or limitations in the script’s ability to represent certain phonemes. Nonetheless, the phonetic resemblance to “Philistine” has drawn considerable attention.

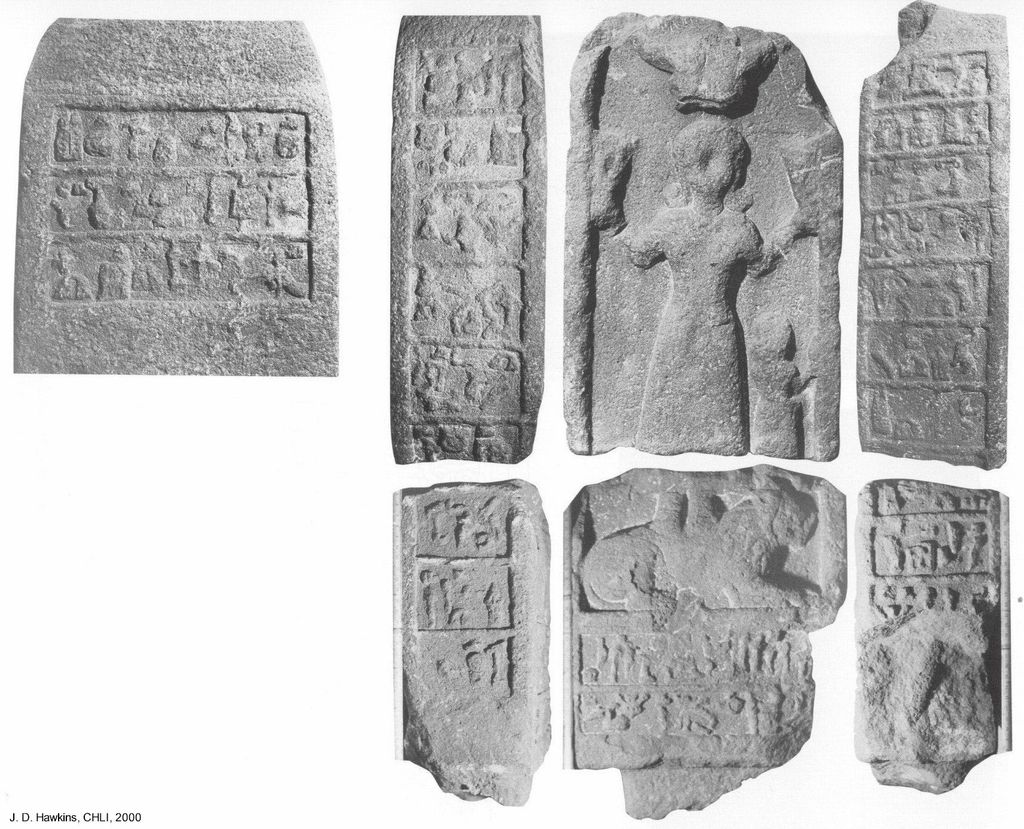

In 2003, excavations at the Citadel of Aleppo yielded a statue of King Taita bearing Luwian inscriptions. These hieroglyphic texts led scholars to identify Taita as ruler of a territory called Palistin, which extended across the Amuq Valley. Several leading Hittitologists, including John David Hawkins, Benjamin Sass, and Kay Kohlmeyer, have proposed a connection between this Syro-Hittite kingdom and the Philistines of the southern Levant. Some interpretations even suggest that the biblical King David may have formed an alliance with a northern ruler identified as Tai(ta) II of Palistin, possibly a leader of a Sea Peoples group.

This theory, however, remains contested. Israeli scholar Itamar Singer has argued that the archaeological evidence from Tell Tayinat, believed to be the capital of Palistin, primarily indicates a Neo-Hittite cultural presence with no discernible Aegean traits. According to this view, if any Philistine migrants had settled in the region, they were likely absorbed by the local Luwian-speaking population, who may have retained the name without preserving the Philistines’ distinct cultural identity.

A separate, more speculative theory has been proposed by Allen Jones, who suggests that the term “Philistine” may derive from the Greek phrase phyle-histia, meaning “tribe of the hearth.” While this idea remains unproven, it finds some archaeological resonance in the presence of hearth-centered architectural features at sites associated with the Philistines, such as Tell Qasile and Ekron.

After centuries of cultural distinction and political influence across the Levant, the Philistines gradually disappeared as a recognizable ethnic group. This decline unfolded alongside the rise of powerful empires that reshaped the ancient Near East. While maintaining relative autonomy for generations, they fell under Neo-Assyrian control beginning in the mid-8th century BC under Tiglath-Pileser III. Some Philistine rulers remained as vassals, but imperial ambitions soon overrode local independence.

By 604 BC, the Neo-Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II decisively ended Philistine autonomy. Following a rebellion, he destroyed key cities such as Ashkelon, Gaza, Aphek, and Ekron. Many Philistines were killed or exiled to Mesopotamia. Early 6th-century BC Babylonian ration lists mention the descendants of Aga, the last king of Ashkelon, and documents from the 5th-century BC Murasu Archive refer to exiled individuals still identifying as “men of Gaza” or Ashkelon. However, over time, this identity faded. By the late 5th century BC, the Philistines no longer appeared in historical or archaeological records as a distinct group.

During the Persian period, the former Philistine cities were repopulated, often by Phoenicians. Although Ashdod’s residents reportedly retained their language—possibly a dialect of Aramaic—there is little evidence of continuity with earlier Iron Age traditions.

The Philistine story is emblematic of the rise and fall of ancient civilizations. From their likely Aegean origins and dominance as the Pentapolis, to their fierce biblical rivalries and rich archaeological legacy, their cultural imprint remains vivid. Though assimilation ended their distinct identity, their history continues to engage scholars, offering vital insights into the complexity and dynamism of the ancient world.