In the competitive world of business, your ability to negotiate a better salary isn’t merely about demanding more; it’s about strategically understanding human dynamics. It requires insight into the motivations, perceptions, and decision-making processes of others. This is precisely where psychology, the scientific study of mind and behavior, becomes your most potent ally. Mastering this fundamental discipline equips you with the unique advantage of comprehending the intricate forces at play in any high-stakes conversation.

Forget superficial tactics. True negotiation prowess stems from a deep, expert-level understanding of what drives individuals and groups. By exploring the core tenets and historical evolution of psychology, we unlock a framework for interpreting human interaction with unparalleled clarity. This journey into foundational psychological knowledge empowers you to approach salary discussions not as adversarial battles, but as opportunities to apply informed strategy, ensuring your value is recognized and rewarded.

This article, structured as a practical guide to essential psychological insights, will reveal how the bedrock principles of human understanding directly translate into powerful negotiation tools. From ancient philosophical inquiries into the soul to the establishment of experimental science, these key developments in psychology offer actionable perspectives for cultivating influence. Prepare to elevate your career trajectory by harnessing the profound wisdom that psychology offers, turning complex human factors into your strategic advantage.

1. **Psychology’s Core Definition: The Scientific Study of Behavior and Mind**At its essence, psychology is “the scientific study of behavior and mind.” This definition is pivotal because it frames human actions and internal experiences within a rigorous, objective inquiry. For anyone preparing for a salary negotiation, understanding this scientific approach means moving beyond assumptions and into an evidence-based interpretation of their counterpart’s responses and their own.

This discipline covers a very wide range of content, including “human and non-human behaviors, including conscious and unconscious phenomena, as well as psychological processes such as thoughts, feelings and motivations”. It might be a good idea to consider how these elements are reflected in negotiations. The recruitment manager’s conscious thinking about budget constraints, unconscious biases, or feelings towards team cohesion can all have an impact on negotiations. Negotiators with such awareness can better interpret verbal cues and non-verbal signals.

This commitment to “scientific study” also underscores the value of systematic observation. Instead of reacting impulsively, a psychologically informed negotiator observes patterns, tests hypotheses about motives, and refines their approach based on data – even if that data is gleaned from subtle conversational exchanges. This foundation is key to developing a robust, adaptable negotiation strategy.

2. **The Interdisciplinary Scope of Psychology: Linking Natural and Social Sciences**Psychology stands uniquely “crossing the boundaries between the natural and social sciences.” This dual nature allows for a comprehensive understanding of human beings, integrating the biological underpinnings of thought with the complexities of social interaction. For the entrepreneur or professional, this means recognizing that negotiation outcomes are shaped by both individual neurological processes and broader organizational dynamics.

As a natural science, psychology delves into “the emergent properties of brains, linking the discipline to neuroscience.” This perspective highlights that even rational decisions have biological roots. While you won’t dissect brains in a meeting, appreciating the brain’s influence on decision-making reminds us of the deep-seated factors that can sway someone’s receptiveness to an offer or argument.

Simultaneously, “as social scientists, psychologists aim to understand the behavior of individuals and groups.” This aspect directly informs negotiation strategy, as you are rarely negotiating in a vacuum. Understanding group norms, company culture, and the individual’s role within that social structure can reveal crucial leverage points. This interdisciplinary lens provides a more complete picture of the human landscape you navigate.

Read more about: Mastering the Art of Influence: A Psychological Journey to Winning Discussions Without Raising Your Voice

3. **The Professional Role of a Psychologist: Understanding Individuals and Groups**Professionals in this field, known as psychologists, are dedicated to “understanding the role of mental functions in individual and social behavior.” Their expertise is not just theoretical; it’s applied. This practical orientation emphasizes that insight into mental processes is a powerful tool for navigating and influencing real-world interactions, including complex salary discussions.

Psychologists delve into the interplay of “perception, cognition, attention, emotion, intelligence, subjective experiences, motivation, brain functioning, and personality.” Imagine the advantage of having a nuanced understanding of these factors in a negotiation. Recognizing how a manager’s personality type might lead them to prioritize certain aspects of an offer, or how their current emotional state might impact their openness, is invaluable.

Their work also extends to “interpersonal relationships, psychological resilience, family resilience, and other areas within social psychology.” These insights are critical. Negotiation is inherently an interpersonal relationship. Understanding resilience and social dynamics can help you maintain composure, interpret the other party’s flexibility, and build a positive foundation even during challenging discussions, ultimately aiming for mutual benefit.

Read more about: Beyond the Whistle: 15 In-Depth Looks at the Sports Psychology Ph.D. Fueling Elite Performance and Coaching Excellence

4. **Key Areas of Psychological Research: Perception, Cognition, Emotion, and Motivation**Psychologists rigorously research core human experiences such as “perception, cognition, attention, emotion, intelligence, subjective experiences, motivation, brain functioning, and personality.” These areas are not just academic curiosities; they are direct drivers of how people interact and make decisions, making them indispensable knowledge for any effective negotiator.

Consider “perception” and “cognition.” Your ability to secure a better salary is heavily influenced by how your employer perceives your value, your contributions, and your future potential. How they process your arguments, compare them to internal benchmarks, and arrive at a decision is a cognitive process. Tailoring your presentation to align with their perceptual filters and cognitive patterns can dramatically enhance your influence.

“Emotion” and “motivation” are often the hidden forces dictating negotiation outcomes. Beyond logical arguments, understanding what truly motivates your counterpart – be it avoiding talent loss, achieving team goals, or maintaining budget discipline – allows you to frame your request in terms that resonate deeply. Similarly, managing your own emotions and recognizing theirs can create a more constructive atmosphere, moving towards a mutually beneficial resolution rather than a standoff.

5. **Psychology’s Foundational Goal: Benefiting Society Through Understanding Human Activity**A core tenet of psychology is its ultimate aim “to benefit society.” This isn’t abstract; it translates into practical applications for improving various “spheres of human activity,” including professional development and, by extension, salary negotiations. The discipline inherently seeks to solve problems and optimize outcomes for individuals and groups.

While therapeutic roles are common, many psychologists “conduct scientific research on a wide range of topics related to mental processes and behavior,” often in “industrial and organizational settings.” This direct engagement with workplace dynamics means that psychological principles are already being applied to understand and improve everything from employee selection to overall organizational effectiveness, providing a rich context for your own negotiations.

This focus on practical benefits means that psychology offers more than just theory; it provides frameworks for understanding human systems. Approaching salary negotiation with this mindset allows you to frame your request not just as a personal gain, but as a contribution to the organization’s goals – whether through increased motivation, improved performance, or retention of valuable talent, thereby aligning your benefit with the broader societal and organizational good.

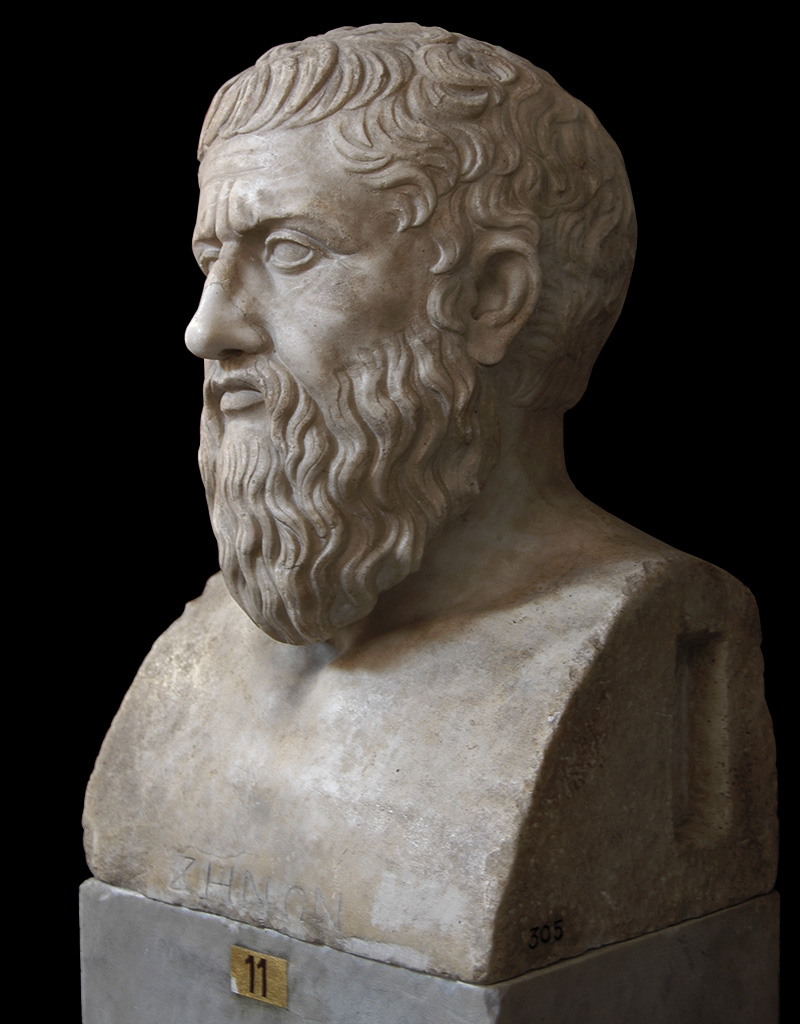

6. **Ancient Roots of Psychological Thought: Early Philosophical Inquiries**The quest to understand the human mind didn’t begin in a laboratory; “the ancient civilizations of Egypt, Greece, China, India, and Persia all engaged in the philosophical study of psychology.” This deep historical lineage underscores the enduring human fascination with consciousness, behavior, and the inner self, providing a profound context for contemporary psychological insights relevant to any human interaction.

Greek philosophers like Plato and Aristotle “addressed the workings of the mind,” with Plato suggesting “the brain is where mental processes take place.” These early thinkers laid conceptual groundwork, initiating the systematic inquiry into internal experience. For the modern professional, recognizing these origins highlights that the complexities of human thought have been pondered and debated for millennia, offering a vast repository of foundational wisdom.

Beyond the West, Chinese philosophy emphasized “purifying the mind in order to increase virtue and power” and viewed “the universe as comprising physical and mental realms, along with the interplay between the two.” The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine even “identifies the brain as the nexus of wisdom and sensation, includes theories of personality based on yin–yang balance, and analyzes mental disorder in terms of physiological and social disequilibria.” These ancient insights into personality and the interplay of internal and external factors offer timeless wisdom for understanding diverse human temperaments and their environmental influences, a crucial aspect of reading any room or individual in a negotiation.

Read more about: Unpacking the Unseen: A Deep Dive into the 14 Fundamental Facets of ‘Concept’ Itself

7. **The Renaissance Emergence of “Psychology”: Defining the Study of the Soul**The very word “psychology” carries a profound history, stemming “from the Greek word psyche, for spirit or soul,” combined with “-logia,” meaning “study or research.” This etymological journey reveals that the initial focus of the discipline was deeply rooted in understanding the inner, non-physical essence of being, highlighting a fundamental human curiosity about consciousness and subjective experience.

A significant milestone was the first documented use of the Latin form “psychiologia” by “Marko Marulić in his book Psichiologia de ratione animae humanae (Psychology, on the Nature of the Human Soul) in the decade 1510–1520.” This marked the formal naming of a field dedicated to the human soul or mind, signifying a critical step in differentiating it from broader philosophical discourse and setting it on its own distinct path of inquiry.

Later, Steven Blankaart’s 1694 “The Physical Dictionary” further solidified this identity, referring to “Anatomy, which treats the Body, and Psychology, which treats of the Soul.” This clear distinction underscores psychology’s enduring focus on the internal world—thoughts, feelings, and motivations—which, though intangible, are immensely powerful in driving behavior. For the astute negotiator, understanding this profound historical emphasis on the ‘soul’ or ‘inner life’ translates into an appreciation for the deeper, often unarticulated, values and principles that guide people’s decisions, enabling more empathetic and effective engagement.

Navigating the complexities of salary negotiation demands more than just a firm grasp of foundational principles; it requires an appreciation for the evolution of psychological thought itself. As we transition from ancient philosophies, we uncover the critical moments when the study of the mind transformed from abstract contemplation into a rigorous, scientific endeavor. Understanding this progression arms you with an even deeper insight into human perception, learning, and the holistic factors that shape every crucial interaction, including your next salary discussion.

8. **Enlightenment Thinkers: Paving the Way for a Science of Mind**The philosophical inquiries into the mind, which began in antiquity, truly started coalescing into something akin to modern psychological thought during the Enlightenment. Thinkers like Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, in Germany, applied his principles of calculus to the mind, suggesting that mental activity existed on an indivisible continuum. His groundbreaking assertion that the difference between conscious and unconscious awareness was merely a matter of degree laid crucial groundwork for understanding the fluid nature of human thought processes.

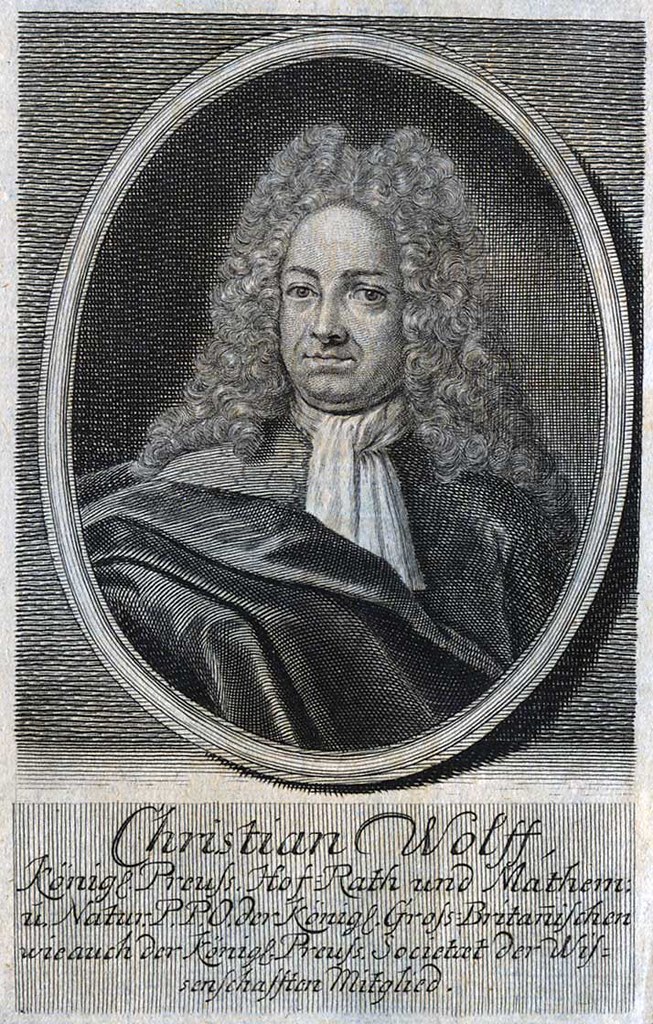

Building on these ideas, Christian Wolff formally identified psychology as its own science, publishing “Psychologia Empirica” in 1732 and “Psychologia Rationalis” in 1734. While Immanuel Kant, a prominent figure, considered psychology an important subdivision of anthropology, he notably rejected the idea of an experimental psychology. He believed that inner observation could only be separated in thought and not manipulated experimentally, a view that highlighted the prevailing skepticism of his era towards quantifying subjective experience.

Despite such reservations, the seeds of scientific inquiry were firmly planted. Ferdinand Ueberwasser, in 1783, designated himself a Professor of Empirical Psychology and Logic, delivering lectures on scientific psychology. Though these efforts faced temporary setbacks, by 1825, the Prussian state established psychology as a mandatory discipline in its educational system. This institutional recognition, even without immediate experimentation, signifies a pivotal shift in how the study of the mind began to be acknowledged as a legitimate and essential field of knowledge.

9. **The Genesis of Experimental Psychology: Wundt’s Revolution**The 19th century ushered in a transformative era for psychology, pushing it firmly into the realm of scientific experimentation. Philosopher John Stuart Mill’s conviction that the human mind was open to scientific investigation, even if inexact, proved highly influential. Mill proposed a “mental chemistry,” suggesting that elementary thoughts could combine to form more complex ideas, a concept that spurred scientists to seek measurable components of mental life.

This pursuit of measurement found its champion in Gustav Fechner, who began conducting psychophysics research in Leipzig in the 1830s. Fechner articulated the principle that human perception of a stimulus varies logarithmically with its intensity, leading to the renowned Weber–Fechner law. His 1860 work, “Elements of Psychophysics,” directly challenged Kant’s earlier skepticism by demonstrating that “mental processes could not only be given numerical magnitudes, but also that these could be measured by experimental methods,” a monumental breakthrough.

It was in this fertile intellectual environment that Wilhelm Wundt, trained by physiologist Hermann von Helmholtz, established the world’s first psychological laboratory at Leipzig University. Wundt’s pioneering work focused on breaking down mental processes into their most basic components, drawing an analogy to the successful investigation of elements in chemistry. This systematic, laboratory-based approach cemented experimental psychology as a distinct scientific discipline, setting the standard for rigorous inquiry into the human mind.

Further solidifying the empirical foundation, German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus, a researcher at the University of Berlin, pioneered the experimental study of memory. He developed quantitative models of learning and forgetting, demonstrating that higher mental processes could also be subjected to systematic measurement and analysis. These early experimentalists provided the blueprint for objective, data-driven insights into cognition, offering invaluable lessons for anyone seeking to analyze and predict human responses in critical situations like negotiations.

10. **Diversifying Approaches: Structuralism, Functionalism, and Early American Pioneers**The impact of Wundt’s laboratory quickly reverberated globally, leading to the establishment of psychology labs across Europe and in the United States. American scholars like G. Stanley Hall, who studied with Wundt, founded an internationally influential lab at Johns Hopkins University. Wundt’s students, including Hugo Münsterberg and James McKeen Cattell, further propagated experimental psychology, with Cattell becoming the first professor of psychology in the United States, greatly influencing the discipline’s academic growth.

Among Wundt’s proteges, Edward Titchener founded the psychology program at Cornell University and championed “structuralist” psychology. This school of thought aimed to analyze and classify different aspects of the mind, primarily through the method of introspection, where individuals reported on their own conscious experiences. While structuralism provided an early, systematic framework, its reliance on subjective reports highlighted the challenges of pure self-observation in reaching universally verifiable scientific truths.

In contrast, William James, John Dewey, and Harvey Carr spearheaded “functionalism,” an expansive approach that emphasized the usefulness of behavior to the individual, heavily influenced by Darwinian evolutionary theory. James’s influential 1890 book, “The Principles of Psychology,” memorably described the “stream of consciousness,” focusing on the dynamic, ever-changing nature of mental experience rather than static components. Functionalism’s emphasis on how mental processes help individuals adapt to their environment offered a more practical and applied perspective.

John Dewey, in particular, integrated psychology with broader societal concerns, championing progressive education and the inculcation of moral values. This functionalist outlook, focused on the purpose and adaptation of mental processes, provides a powerful lens for understanding human motivation. In negotiation, it encourages you to look beyond surface-level statements and consider the underlying purpose or function of your counterpart’s stance, enabling you to craft solutions that genuinely meet their core adaptive needs.

11. **The Power of Conditioning: Behaviorism’s Rise and Physiological Roots**While American psychology branched into structuralism and functionalism, other experimental traditions were emerging globally, particularly with a strong connection to physiology. In South America, Horacio G. Piñero led a distinct strain of experimentalism, while in Russia, researchers like Ivan Sechenov advanced a deterministic view of human behavior, emphasizing brain reflexes as the basis for psychological processes. Sechenov’s 1873 essay, “Who Is to Develop Psychology and How?”, challenged the introspectionist approach, advocating for a focus on observable physiological mechanisms.

This emphasis on observable phenomena found its most profound expression in the work of the Russian-Soviet physiologist Ivan Pavlov. His groundbreaking discovery of “classical conditioning” in dogs, where he demonstrated how a neutral stimulus could be associated with an unconditioned response, provided a powerful new paradigm for understanding learning. Pavlov showed that behavior could be systematically modified through environmental stimuli, a principle that soon found applications far beyond the laboratory, including in human learning and habit formation.

Inspired by these physiological insights, John B. Watson, in 1913, famously asserted the methodological behaviorist view of psychology. Watson argued that psychology should be a “purely objective experimental branch of natural science,” with its theoretical goal being “the prediction and control of behavior.” This radical shift moved psychology away from the study of the subjective “mind” and towards the observable “behavior,” providing a seemingly more rigorous and quantifiable scientific framework.

The behaviorist paradigm offered compelling practical implications for professionals. By focusing on observable actions and their environmental triggers, you can strategically analyze the patterns of interaction in a negotiation. Understanding how certain cues or proposals might elicit predictable responses, or how to condition a more favorable atmosphere, allows for a more controlled and effective approach. This systematic perspective on behavior remains a powerful tool for shaping outcomes and navigating complex interpersonal dynamics.

12. **Psychology’s Institutionalization and Global Reach**As psychological thought evolved and diversified, so too did its formal institutional structures, solidifying its place as a legitimate and influential academic and professional discipline. Early organizations like La Société de Psychologie Physiologique in France paved the way, culminating in the first International Congress of Psychology in Paris in 1889, drawing participants from across the globe. These gatherings were crucial for fostering international collaboration and the exchange of burgeoning psychological ideas.

The American Psychological Association (APA), founded in 1892, grew rapidly from 5,000 members in 1945 to 100,000 today, becoming the oldest and largest national psychology association. Its proliferation of 54 specialized divisions since 1960 reflects the increasing complexity and specialization within the field. On a global scale, the International Union of Psychological Science (IUPsyS), founded in 1951 under UNESCO’s auspices, serves as the world federation of national psychological societies, publishing the “International Journal of Psychology” since 1966.

This institutional growth wasn’t confined to the Western world. Organizations like the Interamerican Psychological Society, founded in 1951, aimed to promote psychology across the Western Hemisphere, while the European Federation of Professional Psychology Associations, established in 1981, represents 30 national associations. Psychology departments proliferated worldwide, often modeled on the Euro-American structure, with new ideas spreading from Japan to China, fostering a truly global academic dialogue.

The establishment of these disciplinary organizations and the legal regulation of psychological practice in many regions underscore the profession’s maturity and its commitment to ethical standards and expert service. For the professional, recognizing the authority and credibility that such institutional backing provides is essential. It highlights the value of structured knowledge and expert-driven approaches, reinforcing that leveraging scientifically validated psychological principles in negotiation is a far cry from anecdotal advice.

13. **Psychology’s Expanding Influence and Enduring Challenges**The 20th century witnessed psychology’s deepening engagement with societal issues, often amplified by global conflicts. During World War I, American psychology gained status as experts administered mental tests like “Army Alpha” and “Army Beta” to nearly 1.8 million soldiers. This applied psychology expanded further during World War II, with psychologists involved in propaganda research and managing the domestic economy. The Cold War saw U.S. military and intelligence agencies, often in collaboration with foundations like Rockefeller and Ford, heavily fund research on psychological warfare, showcasing the practical, sometimes ethically complex, applications of psychological knowledge.

However, the application of psychological principles was not always benign. In Nazi Germany, the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute was rebranded the Göring Institute, and Freudian psychoanalysts, many of whom were Jewish, were expelled and persecuted. A “New German Psychotherapy” was mandated to align Germans with Reich goals, emphasizing “Seelenführung” (soul guidance) to integrate individuals into the Nazi vision of community. Similarly, in the Soviet Union after the Russian Revolution, psychology was promoted to engineer the “New Man” of socialism, emphasizing pedology and child development, though later succumbing to Stalinist purges and ideological control, highlighting how psychological insights can be weaponized or manipulated for political ends.

Chinese psychology, initially modeling itself on the U.S. with influence from John Dewey and the popularization of behaviorism, shifted significantly after the Communist Party gained control. The Stalinist Soviet Union became the dominant influence, with Marxism–Leninism and Pavlovian conditioning guiding behavior change. Chinese psychologists developed concepts like “active consciousness” and “recognition,” where alignment with party doctrine was paramount, illustrating how national ideologies can shape the very definition and application of psychological understanding.

Amidst these varied and often challenging applications, women in psychology played a crucial role in diversifying the field and challenging established norms. Figures like Anna Freud expanded psychoanalysis to children, Leta Stetter Hollingworth debunked myths about women’s intellectual inferiority and menstrual impairment, and Mary Whiton Calkins invented memory techniques. Later, Mary Ainsworth’s work on attachment theory and Mamie Phipps Clark’s doll tests, which influenced the Brown v. Board of Education decision, showcased profound societal impact. Feminist psychologists like Naomi Weisstein critically analyzed the field’s male-centric biases, leading to the formation of organizations like the Association for Women in Psychology, advocating for greater inclusion and diverse perspectives that are essential for a holistic understanding of human experience.

Despite its expanding influence, psychology has continuously faced internal and external scrutiny. Early experimentalists had to distinguish their scientific endeavors from popular fields like parapsychology. Critics, including philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn, argued that psychology lacked a unifying paradigm, labeling it a “soft” science due to its reliance on self-reports and challenges in directly measuring elusive phenomena like personality or emotion. Divisions persist, with some advocating for more qualitative, individual-focused approaches against a perceived “cult of empiricism” derived from physical sciences. Feminist critiques further highlighted how claims to scientific objectivity could obscure the biases of historically male-dominated research. These ongoing debates underscore the dynamic, self-correcting nature of the discipline, constantly refining its methods and expanding its scope to better understand the multifaceted human experience.

This journey through psychology’s evolution reveals a field constantly adapting, deepening its insights, and broadening its impact. From philosophical musings to rigorous experimental methods, from diverse schools of thought to its complex engagement with society, psychology offers an unparalleled toolkit for understanding the human condition. For you, the aspiring master negotiator, this means harnessing a profound appreciation for historical context, recognizing the scientific underpinnings of behavior, and understanding the myriad factors that influence decisions. By internalizing these psychological tenets, you transform negotiation from a mere exchange into a nuanced, strategic dance, where every interaction is an opportunity to leverage deep human understanding for mutual success and a truly better salary.