Ever found yourself wondering if the history books got it all wrong? If there’s a hidden story, a secret plan, or an unseen hand pulling the strings behind the major events that shaped our world? From the whispers in ancient Rome to the persistent questions about literary giants, the human fascination with what lies beneath the surface is a powerful, enduring force. It’s a journey into the shadows where official narratives are questioned and alternative explanations, often far grander and more intricate, take root.

At its heart, this quest for hidden truths often centers around what we call a ‘conspiracy theory.’ But before we dive headfirst into some of history’s most compelling and curious examples, it’s crucial to understand what a conspiracy truly is, and how that differs from a ‘conspiracy theory.’ The distinction is more than just semantics; it’s about the difference between a proven, secret agreement and a belief that such an agreement was the decisive factor in a significant event.

Join us as we pull back the curtain on some of the most intriguing plots and perceived plots, examining their origins, the arguments that sustain them, and the sheer human desire to make sense of a world that often feels random or threatening. We’ll explore how these stories, whether fact or fiction, have shaped our collective imagination and continue to echo through the corridors of time, proving that sometimes, the most captivating tales are the ones that challenge everything we thought we knew.

1. **The Fundamental Definition of Conspiracy: Delving into its Legal and Common Understanding**Before we can even begin to dissect conspiracy theories, it’s vital to grasp what a ‘conspiracy’ itself means. Stripped down, a conspiracy is described as “a secret plan or agreement between people (called conspirers or conspirators) for an unlawful or harmful purpose, such as murder, treason, or corruption, especially with a political motivation, while keeping their agreement secret from the public or from other people affected by it.” This definition immediately highlights the core elements: secrecy, agreement, harmful intent, and often a political motive.

Before we can even begin to dissect conspiracy theories, it’s vital to grasp what a ‘conspiracy’ itself means. Stripped down, a conspiracy is described as “a secret plan or agreement between people (called conspirers or conspirators) for an unlawful or harmful purpose, such as murder, treason, or corruption, especially with a political motivation, while keeping their agreement secret from the public or from other people affected by it.” This definition immediately highlights the core elements: secrecy, agreement, harmful intent, and often a political motive.

In a broader political sense, a conspiracy isn’t just about individual wrongdoing; it can refer to a group “united in the goal of subverting established political power structures.” This subversion might involve “usurping or altering them, or even continually illegally profiteering from certain activities in a way that weakens the establishment with help from various political authorities.” Essentially, it’s about a clandestine effort to change or exploit power dynamics for illicit gain.

The term ‘conspiracy’ inherently carries a negative connotation, implying “wrongdoing or illegality on the part of the conspirators.” Why? Because, as the context suggests, “it is commonly believed that people would not need to conspire to engage in activities that were lawful and ethical, or to which no one would object.” The very act of operating in secret for a particular goal raises suspicions about the legitimacy and morality of that goal.

Interestingly, not all secret activities qualify as conspiracies. For instance, intelligence agencies like the American CIA and the British MI6 operate in secrecy to fulfill their official functions, such as spying on suspected enemies. “This kind of activity is generally not considered to be a conspiracy so long as their goal is to fulfill their official functions, and not something like improperly enriching themselves.” Similarly, sports coaches planning game strategies behind closed doors aren’t conspiring; it’s a legitimate part of their profession.

Crucially, a conspiracy “must be engaged in knowingly.” This means that simply perpetuating social traditions that benefit one group over another, while potentially unethical, isn’t a conspiracy if the participants aren’t consciously doing so “for the purpose of perpetuating this advantage.” The intent is key. And here’s a kicker: if that intent exists, “then there is a conspiracy even if the details are never agreed to aloud by the participants.” The wheels can be in motion, even if no explicit verbal pact is ever made.

2. **Conspiracy vs. Conspiracy Theory: Drawing the Crucial Distinction**Now that we have a solid grasp on what a ‘conspiracy’ entails—a genuine, often unlawful, secret agreement—we can turn our attention to its often-confused cousin: the ‘conspiracy theory.’ The context provides a clear definition: “A ‘conspiracy theory’ is a belief that a conspiracy has actually been decisive in producing a political event of which the theorists strongly disapprove.” This is where the lines often get blurred in public discourse, but the difference is critical: one is an act, the other is a belief about an act.

Conspiracy theories are unique in their construction and resilience. They “tend to be internally consistent and correlate with each other,” often creating a vast, interconnected web of perceived plots. What makes them particularly robust—and sometimes frustrating for those seeking verifiable facts—is that “they are generally designed to resist falsification either by evidence against them or a lack of evidence for them.” Any contradictory information can, paradoxically, be folded into the theory as further proof of the conspiracy’s cleverness.

Political scientist Michael Barkun identified three core principles that typically govern conspiracy theories: “nothing happens by accident, nothing is as it seems, and everything is connected.” This worldview presumes an intentional design behind all significant events, a master plan orchestrated by hidden actors. It’s a compelling framework for making sense of a chaotic world, even if that sense comes at the expense of empirical evidence.

Indeed, this inherent resistance to disproof means that conspiracy theories often become, as Barkun describes, “a closed system that is unfalsifiable, and therefore ‘a matter of faith rather than proof.'” Once embraced, they can be incredibly difficult to dislodge, not because of overwhelming evidence, but because the belief itself becomes a self-sustaining narrative. It’s a powerful psychological phenomenon, especially when compared to the demonstrable reality of actual conspiracies, like the Watergate scandal, which eventually came to light through verifiable facts and investigations.

3. **The Phantom Time Hypothesis: Exploring the Idea of Missing Centuries**Prepare for a theory that challenges the very timeline of our existence! Imagine waking up to find out that a significant chunk of recorded history never actually happened, and we’re all living roughly 300 years in the ‘past.’ This is the audacious claim of the Phantom Time Hypothesis, “one modern conspiracy theory that casts doubt on just about everything in our history after around 614 CE.” It’s a mind-bending idea that suggests our calendar is fundamentally flawed.

This wild theory, which emerged in the 1990s, was put forth by a man named Heribert Illig. According to Illig, the blame for this historical sleight of hand lies squarely with powerful figures from centuries ago. He posited that “Holy Roman Emperor Otto III and Pope Sylvester II added around 300 years to the calendar to place them in power in the year 1000.” Picture that: two powerful individuals literally creating centuries out of thin air, all for a more auspicious date for their reign.

But how, you might ask, could such a colossal deception be maintained? Illig’s theory doesn’t stop at the initial manipulation. He suggests that these conspirators “then concocted a vast conspiracy involving countless monks throughout the Western world who helped fill in the missing centuries with all sorts of tall tales about an emperor named Charlemagne and something called the Middle Ages—most of which, Illig argues, is basically ancient fan fiction.” Entire historical periods, with their wars, kings, and cultural shifts, reduced to elaborate fabrications.

Illig’s primary evidence for this astounding claim rests on “perceived inconsistencies in the Gregorian calendar” as a supposed explanation for how “300 years could have been plucked from thin air.” While the complexities of calendar reform throughout history are undeniable, and early historical records can sometimes be murky, the idea of an entire historical period being conjured is, well, a stretch.

While “it is true that early history often stretched the truth or created it entirely out of whole cloth,” the Phantom Time Hypothesis demands a truly immense leap of faith. As the context notes, “we’d have to discount a lot of primary sources and artifacts to even begin considering Illig’s theory plausible.” Imagine all the archaeological finds, historical documents, and astronomical observations that would need to be recontextualized or simply dismissed. It’s a theory that, while captivating, asks us to ignore a mountain of evidence in favor of a narrative of widespread, centuries-long deception.

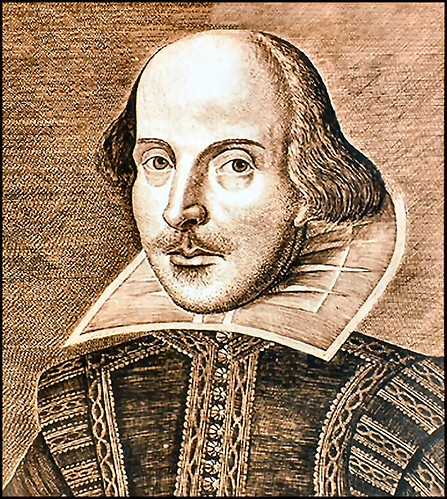

4. **Shakespeare’s True Author: The Enduring Mystery Behind the Bard’s Genius**William Shakespeare, the literary titan whose plays and sonnets have graced stages and inspired generations for centuries, is almost universally revered as the greatest playwright to have ever lived. Yet, for some, the genius attributed to the man from Stratford-upon-Avon isn’t quite so clear-cut. This leads us to one of the most enduring and fascinating literary conspiracy theories: the idea that William Shakespeare didn’t actually write his own plays.

The genesis of this skepticism often stems from the scant biographical information available about Shakespeare himself. As the context notes, “so little is known about Shakespeare as a person—he was born in Stratford in 1564 as the son of a glove-maker, married a woman named Anne Hathaway, and died in 1616—that examining his life in any detail is all but impossible.” For those who demand more robust evidence of his formidable intellect and education, this lack of detail leaves a void, ripe for alternative explanations.

Consequently, “conspiracy theorists have claimed that Shakespeare didn’t exist at all, and was instead merely a pseudonym for an accomplished (and well-educated) writer.” The core argument often hinges on the belief that a man of humble origins, whose documented life shows little evidence of extensive schooling or travel, couldn’t possibly have penned works displaying such profound knowledge of law, court life, foreign cultures, and classical literature. The sheer depth and breadth of the plays, to these theorists, required a different kind of author.

This particular theory “gained prominence during the mid-19th century,” a period when intellectual curiosity and historical scrutiny were on the rise. Two notable books published around this time fueled the debate: one by American playwright Delia Bacon and another by Englishman William H. Smith. Both works proposed an alternative author, suggesting that the name ‘Shakespeare’ was a deliberate smokescreen for someone else’s literary output.

Specifically, “Both argued that Sir Francis Bacon—no relation to Delia—was actually the quill behind masterpieces like Hamlet. Or that Shakespeare was actually a whole gaggle of writers using one pseudonym.” The idea of Sir Francis Bacon, a brilliant philosopher, scientist, and statesman, secretly authoring these plays was appealing to those who felt Shakespeare’s background didn’t align with his output. The “evidence” presented in these books, however, was notably thin, often boiling down to “a lack of evidence” about Shakespeare’s education or documented writing habits, as well as the curious gap where “No plays bearing Shakespeare’s name were published between 1609 and 1622; but in the year 1623 (seven years after Shakespeare’s death) a folio of thirty-six plays was brought out as The Workes of William Sh”.

5. **The Lincoln Assassination Plots: Beyond Booth, Claims of Deeper Orchestrations**The assassination of Abraham Lincoln on April 15, 1865, remains one of the most tragic and pivotal moments in American history. The official story points to John Wilkes Booth as the lone, vengeful actor, a committed Confederate sympathizer. Yet, like many profoundly impactful events, especially those involving the sudden demise of a powerful leader, Lincoln’s death has been fertile ground for conspiracy theories, suggesting a far more complex web of intrigue than the history books typically present.

At the heart of many of these alternative narratives is the belief that Booth was merely a pawn, a trigger-man in a much larger, shadowy plot. One such theory, tantalizingly mentioned in our context, posits that “Lincoln’s Secretary of War was behind his assassination.” Edwin Stanton, Lincoln’s fiercely loyal, yet often controversial, Secretary of War, might seem an unlikely suspect. However, in the realm of conspiracy, anyone with power, access, or a perceived motive can become a target of suspicion.

Such theories often capitalize on unanswered questions or perceived inconsistencies in the official investigation. Was Booth truly acting alone, or were there more influential figures pulling the strings from behind the scenes? The sheer audacity of the act, coupled with the immense political upheaval of the post-Civil War era, made it almost inevitable that people would search for a grander explanation, a more organized effort to destabilize the Union.

The idea that high-ranking government officials might be involved taps into a deep-seated human distrust of power, a theme common across many conspiracy theories. If the very people meant to protect the nation’s leader were complicit in his death, it would imply a betrayal of the highest order, shaking the foundations of trust in leadership itself. These theories resonate because they offer an explanation for a seemingly incomprehensible act, suggesting that major events are never truly random or the work of a single individual.

While historical consensus continues to uphold the official account of Booth’s actions, the theories surrounding Lincoln’s assassination persist. They serve as a powerful reminder of how human psychology grapples with tragedy, often seeking order and intention in chaos. The notion of a meticulously planned conspiracy, even if unproven, offers a sense of understanding, albeit a dark one, that a lone gunman sometimes cannot provide.

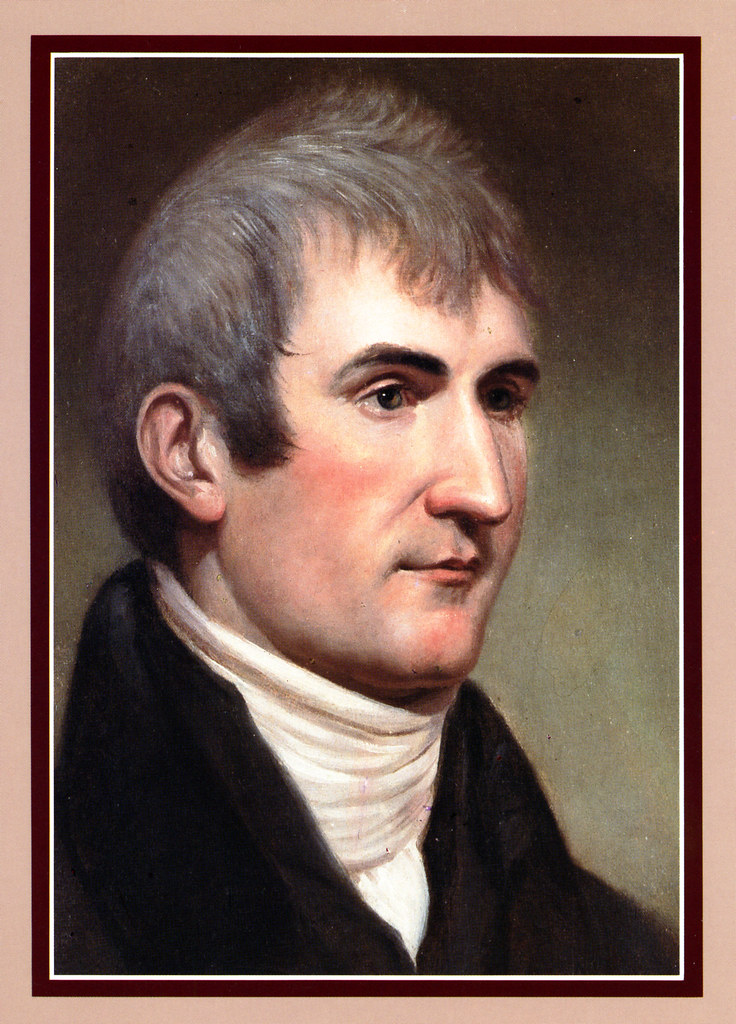

6. **Meriwether Lewis’s Mysterious Death: Investigating the Circumstances of his Demise**Meriwether Lewis, forever etched into American lore as the co-leader of the epic Lewis and Clark Expedition, is a figure synonymous with exploration and pioneering spirit. His journey across the newly acquired Louisiana Purchase was a triumph of endurance and discovery. However, the story of his life concludes not with accolades and a peaceful retirement, but with a lingering mystery surrounding his death in 1809 at Grinder’s Stand, an inn on the Natchez Trace in Tennessee.

The official narrative states that Lewis died by suicide, suffering from depression and possibly alcoholism. He was found with two gunshot wounds, one to the head and one to the chest. However, this explanation has not satisfied everyone, and a persistent conspiracy theory maintains that “Meriwether Lewis didn’t die by suicide—he was murdered.” This alternative view speaks to our innate human tendency to question sudden, tragic endings, especially for figures of such historical significance.

Proponents of the murder theory often point to several aspects of the case: the ambiguity of the wounds (could he have shot himself twice?), the lack of a clear suicide note, and the potential political enemies Lewis had amassed during his turbulent tenure as governor of the Louisiana Territory. Was his death too convenient for those who might have wished him ill? These are the kinds of questions that fuel conspiratorial thinking, demanding a more deliberate, sinister explanation than a self-inflicted demise.

The idea that ‘nothing happens by accident,’ a core principle of conspiracy theories, certainly applies here. For many, a figure as important as Meriwether Lewis could not simply succumb to personal demons; there had to be an external force at play. This search for agency and design in the face of tragedy is a powerful psychological driver, offering a more satisfying, albeit unsettling, narrative than the unpredictable nature of mental health or unfortunate circumstance.

While historical investigations and forensic analyses have largely supported the suicide theory, the questions endure. The Meriwether Lewis conspiracy theory highlights how the unexplained deaths of prominent figures often become canvases onto which we project our anxieties and our desire for definitive, perhaps dramatic, answers. It’s a reminder that even foundational American heroes can become subjects of enduring historical debate and speculation.

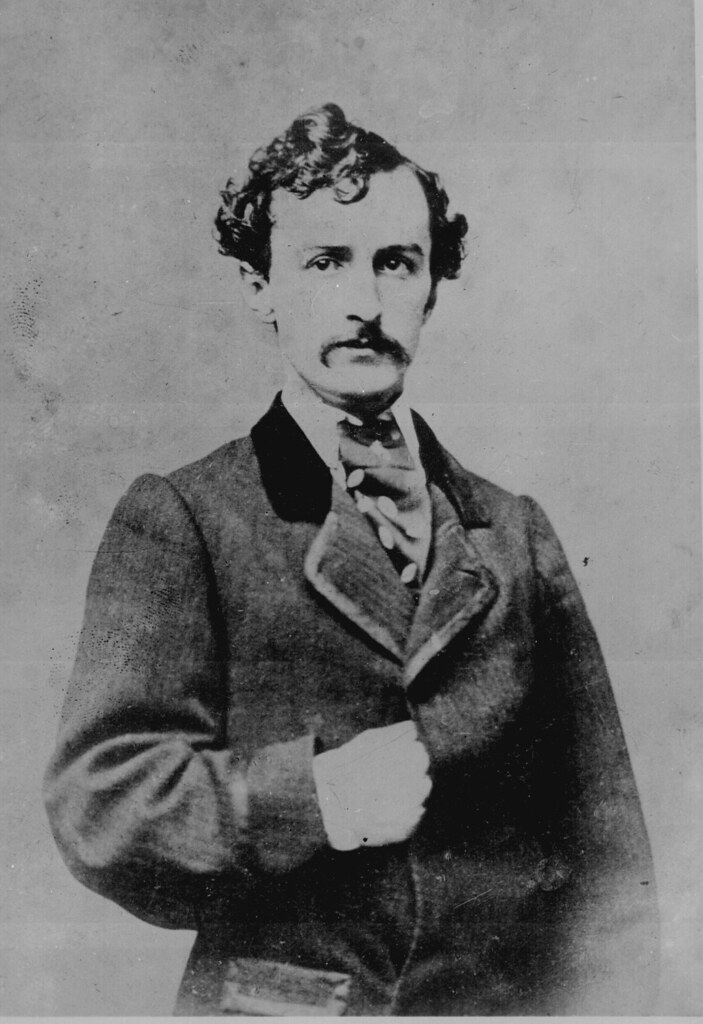

7. **John Wilkes Booth Wasn’t Killed: The Great Escape Theory**Just as the assassination of Abraham Lincoln on that fateful April night in 1865 remains one of America’s most profound tragedies, the fate of his assassin, John Wilkes Booth, has spawned its own persistent currents of doubt. The official account tells us Booth was cornered and killed in a barn in rural Virginia less than two weeks after the crime, brought down by a Union soldier named Boston Corbett. But for some, that tidy conclusion simply doesn’t sit right.

This theory suggests that the official narrative of Booth’s death was a cleverly orchestrated cover-up, a perfect example of the belief that ‘nothing is as it seems.’ Proponents argue that the man killed in the barn wasn’t Booth at all, but a look-alike, allowing the real assassin to escape justice and live out his days under a new identity. Such a dramatic twist appeals to the inherent distrust of official narratives that often fuels conspiratorial thinking.

The allure of such a theory lies in its ability to introduce a deeper layer of intrigue to an already sensational event. It posits that a significant historical outcome—Booth’s death—was not as it was presented, challenging the accepted facts and demanding a more complex, hidden explanation. This aligns perfectly with the conspiracy theorist’s worldview, where ‘nothing happens by accident’ and every major event is part of a larger, intentional design.

Indeed, the persistent questioning of Booth’s demise reflects a broader human desire to find order and intention even in chaos, and a fascination with the idea that powerful figures or circumstances can manipulate events. The theory, like many, often thrives on perceived inconsistencies in official reports or the simple psychological need to believe there’s more to the story than meets the eye, making it a compelling piece of historical speculation.

8. **The U.S. Developed an Invisible Warship: Cloaked in Secrecy**The realm of military innovation and covert operations has always been a hotbed for speculation, and few ideas are as captivating as that of an ‘invisible warship.’ While stealth technology is a very real, albeit modern, development, a long-standing conspiracy theory claims that the U.S. government not only pursued but successfully developed a ship capable of invisibility decades ago. This isn’t just about radar evasion; it’s about making a vessel literally vanish before one’s eyes.

This theory often centers around whispers of secret projects, drawing on the idea that intelligence agencies like the CIA and MI6 necessarily operate in secrecy. It posits that the U.S. Navy conducted experiments that went far beyond conventional understanding of physics, attempting to bend light or manipulate electromagnetic fields to render entire vessels undetectable, not just to radar, but to the eye. The very nature of such a claim, lacking public evidence, only strengthens the conspiratorial belief that it’s being intentionally hidden.

The notion of an invisible warship exemplifies the core tenets of conspiracy theories: ‘nothing is as it seems’ and ‘everything is connected.’ It suggests that the official capabilities of military technology are merely a façade, concealing far more advanced and potentially dangerous achievements. The government, according to this narrative, is engaged in secret plans for ‘unlawful or harmful purpose’ or to ‘subvert established political power structures,’ thereby aligning with the definition of a true conspiracy.

These theories thrive in the absence of complete information, allowing the imagination to fill in the gaps with the most dramatic and unsettling possibilities. The idea of such a formidable, undetectable weapon speaks to a collective fascination with technological breakthroughs and a deep-seated suspicion that governments possess capabilities far beyond what they publicly admit, continually pushing the boundaries of what is believable and what is merely a matter of faith.

9. **Queen Elizabeth I Was Actually a Man: The Bisley Boy Enigma**Queen Elizabeth I, the iconic Virgin Queen, ruled England with remarkable strength and intellect, leaving an indelible mark on history. Her life, though well-documented, is not immune to the swirling currents of conspiracy. One of the most intriguing and persistent theories challenges her very identity: the claim that Queen Elizabeth I was actually a man, or more precisely, that the historical Elizabeth died in childhood and was secretly replaced by a boy.

This fascinating theory, often dubbed the ‘Bisley Boy’ legend, suggests that during her childhood, Elizabeth Tudor fell ill and died while staying in the village of Bisley. Fearing the wrath of her father, King Henry VIII, for failing to protect his daughter, her governess supposedly replaced the deceased princess with a local boy who bore a striking resemblance to her. This boy, according to the theory, then grew up to become the formidable Queen Elizabeth I.

The claim is a masterclass in the conspiratorial principle that ‘nothing is as it seems.’ It postulates a massive deception at the highest levels of the English court, sustained for decades, affecting the entire lineage and perception of royal power. The perceived lack of specific biographical details about a certain period of Elizabeth’s childhood, combined with her later resolute refusal to marry or produce an heir, are sometimes cited as ‘evidence’ by proponents of this extraordinary tale.

Such a theory deeply taps into societal anxieties about legitimacy, gender, and power, seeking to undermine the established order by revealing a fundamental, hidden falsehood at its very foundation. It exemplifies how conspiracy theories often try to ‘make sense of social forces that are self-relevant, important, and threatening,’ offering a dramatic, if unproven, explanation for historical mysteries and challenging everything we thought we knew about one of England’s most celebrated monarchs.

10. **Lewis Carroll Was Jack the Ripper: An Unlikely Suspect**On one side, we have Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, better known as Lewis Carroll, the brilliant and eccentric author of ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland,’ a beloved figure of Victorian literature. On the other, we have Jack the Ripper, the infamous, unidentified serial killer who terrorized London’s Whitechapel district in 1888, leaving a trail of gruesome murders and unanswered questions. These two figures seem worlds apart, yet a chilling conspiracy theory links them in the most unsettling way.

The theory suggests that the whimsical creator of Wonderland was, in fact, the notorious Ripper. Proponents of this startling claim often delve into Carroll’s writings, anagrams, and perceived dark undertones in his works, searching for hidden clues or confessions. They might scrutinize his movements, his known acquaintances, or his psychological profile, attempting to twist seemingly innocent details into sinister evidence of a double life.

This particular theory thrives on the ‘everything is connected’ principle, attempting to forge links between disparate elements—a respected author and a brutal killer—through a web of circumstantial interpretation. The lack of concrete evidence, far from discrediting the theory, can actually be reinterpreted as further proof of the conspirator’s cleverness, fitting into the ‘closed system’ nature of conspiracy theories that are ‘designed to resist falsification either by evidence against them or a lack of evidence for them.’

Ultimately, the idea of Lewis Carroll as Jack the Ripper speaks to our enduring fascination with the dark side of human nature and the desire to unmask celebrated figures as hidden monsters. It’s a prime example of how the most enduring mysteries, especially those involving unsolved crimes, can become magnets for highly imaginative, yet unsubstantiated, explanations that captivate the public imagination, often becoming ‘a matter of faith rather than proof.’

11. **Winston Churchill’s Father (or Queen Victoria’s Grandson) Was Jack the Ripper: Royal Intrigue and Infamy**

The mystery of Jack the Ripper’s identity remains one of history’s most tantalizing cold cases, and naturally, such an enduring enigma has drawn the most prominent names into its orbit. Not content with linking a beloved children’s author to the crimes, some theories have sought to elevate the Ripper’s social standing dramatically, pointing fingers at individuals within the upper echelons of British society, including figures connected to royalty and future political giants.

Two of the most sensational claims involve Lord Randolph Churchill, the father of future Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Prince Albert Victor, the Duke of Clarence and Avondale, who was Queen Victoria’s grandson and second in line to the throne. These theories typically suggest that the Ripper was someone powerful enough to orchestrate a cover-up, benefiting from influence and connections that allowed the crimes to remain unsolved and the true culprit protected from justice.

For these theories, the motive often involves deep-seated secrets, perhaps related to royal scandals or illicit affairs, with the murders serving either as a brutal means to silence witnesses or as the deranged acts of someone protected by their status. Such narratives inherently tap into a profound distrust of elites, embodying the principles that ‘nothing is as it seems’ and that a powerful group might conspire for ‘unlawful or harmful purpose’—in this case, to commit murder and evade accountability.

These high-profile accusations against powerful figures resonate because they offer an explanation for the Ripper’s escape from justice that goes beyond mere investigative incompetence. They suggest a deliberate suppression of truth, reinforcing the idea that ‘everything is connected’ in a web of elite conspiracy. The enduring appeal of these theories highlights how deeply people want to believe that important historical events, especially shocking crimes, are rarely random but instead the result of deliberate, often sinister, design, no matter how extraordinary the claims.

Our journey through these intriguing historical mysteries reveals a common thread: the human mind’s insatiable desire to find order, meaning, and intention, even in the most chaotic or inexplicable events. From phantom centuries to royal imposters and shadowy assassins, conspiracy theories offer a compelling alternative to the often-messy, random, or inconvenient truths of history. They are, as political scientist Michael Barkun noted, ‘a closed system that is unfalsifiable, and therefore ‘a matter of faith rather than proof.” While skepticism and questioning authority are vital, it’s also crucial to discern between genuine, verifiable conspiracies and narratives that defy evidence, becoming self-sustaining beliefs. Recent research, for instance, has found very limited evidence that psychological distress directly increases belief in such theories, or vice versa, suggesting they might reflect a more stable worldview rather than temporary emotional states. Perhaps, rather than focusing solely on emotional factors, fostering critical thinking and an analytical mindset might be our best tools for navigating the fascinating, yet often perilous, world of hidden truths and perceived plots.