Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” stands as an unshakeable pillar in American literature, a haunting and profoundly moving novel that continues to captivate readers decades after its 1987 publication. Winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, it’s a testament to the enduring power of storytelling, delving into the harrowing aftermath of slavery with an unflinching gaze and remarkable empathy. This isn’t just a book you read; it’s an experience that settles deep within your soul, challenging perceptions and illuminating the resilience of the human spirit.

Set in post-Civil War Ohio, the novel centers on Sethe, a formerly enslaved woman whose Cincinnati home at 124 Bluestone Road is haunted by a malevolent spirit, believed to be her eldest daughter. Morrison masterfully weaves a narrative that is both intensely personal and sweepingly historical, exploring the psychological scars left by the peculiar institution. It’s a story that asks us to confront the unthinkable, to understand the depths of maternal love, and to witness the arduous journey toward healing and self-reclamation.

As we embark on this in-depth exploration, we’ll journey through the lives of “Beloved”‘s most unforgettable characters, those who anchor this narrative of memory, trauma, and identity. We’ll uncover how their individual experiences forge a collective tapestry of survival and profound struggle, making them not just characters on a page, but indelible figures who resonate with the echoes of a brutal past. Get ready to meet the souls who make “Beloved” an absolute masterpiece.

1. **Sethe**At the heart of “Beloved” beats the formidable and fractured spirit of Sethe, the novel’s protagonist and an escapee from the brutal Sweet Home plantation. Her life at 124 Bluestone Road is a constant negotiation with a traumatic past, manifest physically in the “tree on her back”—scars from being whipped—and spiritually through the haunting presence of her murdered child. Sethe’s journey is one of relentless survival, driven by a profound, almost terrifying, maternal love that dictates her most drastic actions.

Her defining act, the infanticide of her eldest daughter, is the pivot around which much of the novel’s emotional weight revolves. When four horsemen came to return her and her children to slavery, Sethe, “terrified of returning to Sweet Home and its vicious manager Schoolteacher,” ran to the woodshed with her children, attempting to kill them all, “but only managed to kill her eldest daughter.” She articulates her motivation with a heartbreaking clarity: she was “trying to put my babies where they would be safe,” believing death to be a preferable alternative to the horrors of re-enslavement. This act, while condemned by the community, is seen by Sethe as the ultimate act of protection, a “thick love” that stands against the “thin love” of societal judgment.

Sethe’s resilience is intertwined with her repression of these traumatic memories. She carries a heavy burden of guilt and grief, yet her capacity for love, though warped by her experiences, remains fiercely potent. Her relationship with Paul D eventually offers a path toward healing, a chance for her “self that is no self” to be remade. In the novel’s poignant conclusion, devastated by Beloved’s disappearance, she remorsefully tells Paul D that Beloved was her “best thing,” to which he replies, “that Sethe is her own ‘best thing’,” prompting her to question, “‘Me? Me?'” This moment encapsulates her journey of self-discovery, moving from a self-definition solely tied to her children and her past to a nascent understanding of her own worth.

Read more about: Seriously What Happened? 9 Vintage Sodas That Vanished From Store Coolers — A Bubbly Trip Down Memory Lane.

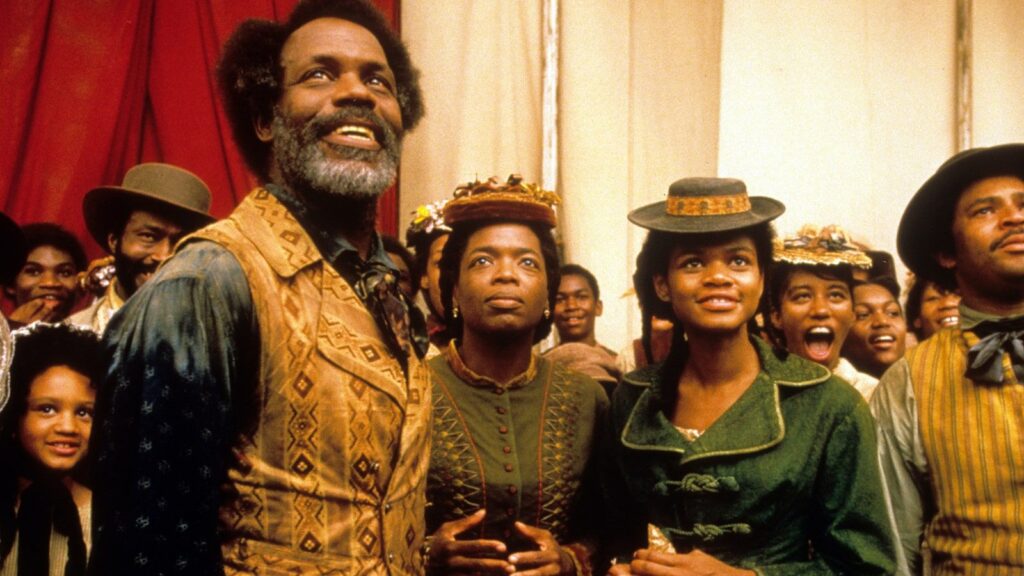

2. **Beloved (the character)**The character of Beloved is perhaps the most enigmatic and unsettling presence in the entire novel, serving as both a literal figure and a powerful metaphor for the unaddressed trauma of slavery. She “mysteriously appears from a body of water near Sethe’s house” and is found “soaking wet on the doorstep” by Sethe, Paul D, and Denver. Her arrival immediately ceases the haunting at 124, leading many, including Sethe herself, to believe she is the murdered baby returned to life. Morrison explicitly states that “the character Beloved is the daughter who Sethe killed,” her name derived from the simple “BELOVED” engraving Sethe could afford on her baby’s tombstone.

Beloved is more than just a ghost; she is a catalyst, forcing the characters, particularly Sethe, to confront “repressed trauma of the family to the surface.” Her childlike behavior quickly devolves into an “angry and demanding” presence, throwing tantrums and gradually “consuming Sethe’s life.” She grows “bigger and bigger, eventually taking the form of a pregnant woman,” a physical manifestation of her parasitic nature, draining Sethe emotionally and physically as Sethe attempts to atone for her past actions.

The debate among scholars about “whether she is actually a ghost or a real person” underscores her symbolic depth. Some reviewers, assuming her to be a supernatural incarnation, initially faulted the novel as a “confusing ghost story.” However, as Elizabeth B. House argues, an interpretation where Beloved is “not a ghost” but rather “a story of two probable instances of mistaken identity” – where a young enslaved woman, traumatized by her own loss, believes Sethe is her mother, and Sethe, longing for her dead daughter, easily accepts this – “clears up many puzzling aspects of the novel and emphasizes Morrison’s concern with familial ties.” This dual interpretation makes Beloved a profoundly complex character, embodying both personal and collective historical suffering.

3. **Paul D**Paul D, one of the formerly enslaved men from Sweet Home, serves as a crucial figure in Sethe’s life and a powerful lens through which the masculine experience of slavery is explored. He carries the weight of his past, including horrific memories of “ual violence inflicted upon him and the other men while in a chain gang.” He encapsulates his painful memories within a metaphorical “tobacco tin” for a heart, a mechanism of repression that keeps his spirit from shattering entirely under the weight of his suffering. His constant movement before arriving at 124 signifies his ongoing struggle to find a stable sense of self and belonging.

Upon his arrival, Paul D is a force for change, “forc[ing] out the spirit” haunting 124, disrupting the stagnant grief that has enveloped Sethe and Denver. He attempts to forge a new future with Sethe, desiring to start a family, but is blindsided by the community’s ostracization of Sethe. It is Stamp Paid who reveals the truth of Sethe’s past by showing Paul D “a newspaper clipping of an article about a fugitive woman who killed her child.” This revelation deeply challenges Paul D’s understanding of Sethe and the nature of her love, leading him to accuse her love of being “too thick” and to temporarily abandon her, unable to reconcile the loving woman he knows with the infanticide.

Yet, Paul D’s own journey of healing is intricately tied to Sethe. “Her tenderness about his neck jewelry — its three wands, like attentive baby rattlers, curving two feet into the air” allows him to retain his “manhood,” because “she never mentioned or looked at it, so he did not have to feel the shame of being collared like a beast.” This profound acceptance is key to his own ability to process his trauma. Ultimately, he returns to a bed-ridden Sethe, offering her the affirmation she desperately needs, telling her that *she* is her own “best thing,” an act that signifies his growth and his commitment to helping Sethe rebuild herself. Paul D’s character highlights the complex path to recovery, emphasizing the power of empathy and mutual support in overcoming the dehumanizing legacy of slavery.

Read more about: Hold Up! 12 Electric Vehicles That Have Owners Wishing for a Do-Over

4. **Denver**Denver, Sethe’s only surviving child living at 124 Bluestone Road, begins the novel as a “shy, friendless, and housebound” individual, deeply isolated by her mother’s past actions and the haunting of their home. Her life is shaped by a profound dependency on her mother and, initially, a unique bond with the “ghost of Sethe’s eldest daughter,” whom she views as her “only companion.” Her journey throughout “Beloved” is arguably one of the most transformative, evolving from a withdrawn child to a protective and independent woman.

Beloved’s mysterious arrival initially deepens Denver’s attachment, as she “is eager to care for the sickly Beloved, whom she begins to believe is her older sister come back.” This newfound companionship temporarily pulls Denver out of her solitude, but as Beloved’s presence becomes more demanding and malevolent, consuming Sethe, Denver is forced to confront her deepest fears. She reveals her fear of Sethe, “having known that she killed Beloved, but not having understood why, and that her brothers shared this fear and ran away due to it.” This realization marks a crucial turning point, pushing Denver towards action.

The true emergence of Denver’s heroism lies in her decision to break the cycle of isolation and seek help from the community that had long shunned them. She realizes that “neither Beloved nor Sethe seemed to care what the next day might bring. Denver knew it was on her. She would have to leave the yard; step off the edge of the world, leave the two behind and go ask somebody for help.” This courageous act, metaphorically “step[ing] off the edge of the world,” not only secures her personal independence by gaining a job from Mr. Bodwin but also directly leads to the community’s intervention to exorcise Beloved. Denver’s growth demonstrates that heroism isn’t always about grand, singular acts, but often about the quiet courage to defy personal confinement and reach out for collective support, thereby securing a future for herself and her mother.

Read more about: Beyond the Alarm: 13 Subtle Silent Heart Attack Signs Women Over 50 Must Recognize for Lifesaving Early Action

5. **Baby Suggs**Baby Suggs, Sethe’s revered mother-in-law and Halle’s mother, embodies a profound journey from enslavement to spiritual leadership, and ultimately, to a quiet resignation. Her freedom was purchased by her son, Halle, a testament to the powerful bonds and sacrifices within enslaved families. After gaining her freedom, she settles in Cincinnati and becomes “a respected leader in the community, preaching for the Black people to love themselves because other people will not.” Her sermons in the Clearing are powerful affirmations of self-worth and communal healing, encouraging a people scarred by dehumanization to embrace their bodies, their hearts, and their lives.

However, Baby Suggs’s influence and the community’s trust are tragically eroded by two key events: her transformation of donated food into a lavish feast, which “earning their envy” from the struggling Black community, and Sethe’s act of infanticide, which horrified them. This communal rejection, coupled with the profound despair caused by Sethe’s actions, leads Baby Suggs to retire from her public role and, essentially, from life itself. She retreats to her bed, where she spends her remaining eight years, “think[ing] about pretty colors,” a poignant escape from the overwhelming pain and the “disinterested performance” of living.

Baby Suggs represents a different way of coping with the trauma of slavery than Sethe. She “dealt with this by refusing to become close with her children and remembering what she could of them,” a stark contrast to Sethe’s fierce, possessive love. Her life illustrates the fragility of community, the burden of leadership, and the devastating impact of both external and internal betrayals. Her quiet decline underlines a deep sorrow, a spirit broken not just by past suffering, but by the inability of her community to fully embrace the self-love she championed or to extend forgiveness in the face of unspeakable tragedy.

Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’ isn’t just a story of individuals; it’s a profound tapestry woven with universal themes that resonate deeply with the human experience, particularly the enduring scars of slavery. Having journeyed through the lives of Sethe, Beloved, Paul D, Denver, and Baby Suggs, we now turn our gaze to the thematic pillars that elevate this novel from a powerful narrative to an unforgettable masterpiece. These are the core ideas that Morrison skillfully unpacks, forcing us to confront the past, understand resilience, and ponder the very essence of humanity.

Get ready to dive into the heart of ‘Beloved’ as we unravel the intricate threads that define its enduring legacy. Each of these themes is not merely an academic concept but a lived reality for the characters, a profound truth etched into the very fabric of their existence. Understanding them is key to truly grasping the monumental impact of Morrison’s vision.

Read more about: Unraveling the Heartbreak: Characters from Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’ Who Still Haunt Us

6. **Mother-daughter relationships**The complexities of mother-daughter relationships form one of the most poignant and agonizing thematic pillars in ‘Beloved,’ showcasing how these vital bonds, when fractured by the institution of slavery, can lead to devastating consequences. Sethe’s own journey exemplifies this, as her fierce, almost dangerous, maternal passion ultimately inhibits her individuation, leading to the unthinkable act of killing her eldest daughter. This desperate act, intended to salvage her ‘fantasy of the future’ from the horrors of enslavement, ironically becomes the very thing that prevents the full development of her ‘self’ and leaves her surviving daughter, Denver, isolated and estranged from the Black community.

Morrison masterfully illustrates how the traumas of slavery warp these foundational relationships. Sethe, consumed by her past and the fervent need to protect, initially fails to recognize Denver’s critical need for interaction with the wider Black community, a crucial step for Denver to enter into womanhood. It is only through the harrowing experience with Beloved and the subsequent community intervention that Denver is truly able to establish her own self and embark on her journey of individuation, eventually securing her own job and personal independence.

The novel suggests that Sethe’s own individuation, her ability to truly reclaim her self, only becomes possible after Beloved’s exorcism. This liberation allows her to finally accept the first relationship that is completely ‘for her’—her bond with Paul D—freeing her from the self-destructive patterns tied to her children and her traumatic past. Morrison also presents Baby Suggs as a contrasting example; having lost so many children to slavery, she coped by refusing to become too close to them, remembering only what she could, highlighting the devastating consequences of slavery on the most fundamental of human connections. Sethe’s trauma from having her milk stolen, a symbolic bond broken, further underscores the profound maternal suffering ingrained by the system.

Read more about: Unraveling the Heartbreak: Characters from Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’ Who Still Haunt Us

7. **Psychological effects of slavery**The psychological effects of slavery are meticulously explored throughout ‘Beloved,’ revealing how the suffering endured under this brutal institution led former slaves to repress their memories, resulting in a fragmentation of the self and a profound loss of true identity. Characters like Sethe, Paul D, and Denver all grapple with this loss, their pasts so painful that they attempt to deny and keep their earlier identities at bay, creating what the novel describes as a ‘self that is no self.’ This repression prevents genuine healing and self-understanding.

Beloved, the enigmatic character, serves as a powerful catalyst in this thematic exploration. Her mysterious arrival forces these characters to confront their deeply buried, repressed memories, ultimately paving the way for the reintegration of their fractured selves. Morrison illustrates how slavery brutally splits a person, rendering their identity a collection of painful, unspeakable memories. To truly heal and humanize, the novel suggests, one must constitute this ‘self’ in language, reorganize the traumatic events, and bravely retell those painful memories, making them real through acknowledgment.

The challenge for Sethe, Paul D, and Baby Suggs lies in their struggle to remake themselves because they initially try to keep their pasts at bay, harboring a desire for an ‘uncomplicated past’ and a crippling fear that remembering will lead them to ‘a place they couldn’t get back from.’ The novel profoundly asserts that the ‘self’ is located in a word, defined by others, and that the power lies in the audience—or more precisely, in the word itself. Once the word changes, so too can identity, emphasizing the arduous but essential journey of confronting and articulating one’s traumatic history to achieve wholeness.

Read more about: Unraveling the Heartbreak: Characters from Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’ Who Still Haunt Us

8. **Definition of manhood**The novel brilliantly dissects the concept of manhood and masculinity, especially as it was distorted and challenged by the brutal realities of slavery and the restrictive norms of post-Reconstruction white society. Paul D, a central male figure, serves as a poignant illustration of this theme, carrying the weight of horrific memories, including ‘ual violence inflicted upon him and the other men while in a chain gang.’ His metaphorical ‘tobacco tin’ heart, where he represses his suffering, speaks volumes about the emotional mechanisms enslaved men developed to survive.

Morrison delves into Paul D’s perception of manhood through his ‘half-formed words and thoughts,’ allowing the audience to glimpse the internal turmoil caused by the constant challenge to his identity from white cultural values. Scholar Zakiyyah Iman Jackson notes how Paul D’s reduced manhood is explicitly linked to a ‘discourse of animality,’ highlighting the dehumanizing lens through which enslaved Black men were viewed. He is a victim of racism, his dreams and goals—despite his sacrifices—remain frustratingly out of reach due to societal limitations, leading him to believe that society owes him recompense for his suffering.

The context of the Reconstruction era, with Jim Crow laws limiting Black men’s movement and involvement, further underscores this struggle. Black men were forced to forge identities within a society that constantly constrained them to a ‘lower-status’ in the social hierarchy. Stamp Paid’s observation of Paul D ‘stripped of the very maleness that enables him to caress and love the wounded Sethe,’ while sitting on the church steps, powerfully visualizes his diminished status. Paul D’s recurring posture of sitting on a ‘base of some sort or a foundation like a tree stub or the steps’ symbolically exemplifies his societal place: the essential ‘foundation of society’ through his labor, yet denied the respect and agency of his manhood.

Read more about: Unraveling the Heartbreak: Characters from Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’ Who Still Haunt Us

9. **Family relationships**Family relationships, often fragmented and deeply scarred by the institution of slavery, form an instrumental and heartbreaking element in ‘Beloved,’ visualizing the immense stress and dismantlement African-American families endured during this era. The inherent cruelty of the slavery system denied enslaved individuals rights to themselves, their families, their belongings, and most tragically, their children. This horrific reality fundamentally reshaped the very definition of familial love and protection, pushing individuals to unimaginable extremes.

Sethe’s defining act—the infanticide of her daughter, Beloved—is presented within this context as what Sethe herself believed to be a ‘peaceful act,’ an ultimate measure to spare her child from the abominations of re-enslavement. While devastating, this act highlights the fractured state of family bonds, born from the brutal conditions that made such choices seem, to some, like salvation. After the Emancipation Proclamation, formerly enslaved families were left ‘broken and bruised,’ struggling to piece together lives that had been systematically torn apart, often turning to the supernatural for solace and understanding in a world where societal institutions offered little support.

The ghostly presence of Beloved, who was murdered at Sethe’s hands, serves as a vivid manifestation of these fractured family relationships and the enduring mental strife faced by the protagonist. Her mysterious appearance after Sethe, Denver, and Paul D visit the carnival underscores the idea that trauma and unaddressed grief can haunt a home, a ‘place of vulnerability, where the heart lies.’ Sethe’s steadfast belief that Beloved is her returned daughter, despite Paul D and Baby Suggs’s skepticism, powerfully displays how deep-seated longing and guilt can warp perception, making the mental anguish of fragmented family ties a palpable presence within the narrative.

Read more about: The Strategic Deals and Operations Driving Multi-Million Dollar Success for Harrison Ford Dealerships

10. **Heroism**’Beloved’ offers a nuanced and profound redefinition of heroism, presenting it not as an absolute concept of supernatural powers or unparalleled valor, but as the ability to do what one deems right in the face of immense opposition, inspiring others to escape the pain of their past. Morrison skillfully crafts Sethe and Denver as unconventional heroes, their actions challenging conventional societal norms and demonstrating that true courage often arises from deeply personal and often agonizing choices.

Sethe’s decision to kill her child, Beloved, deeply scorned by the community, is justified by her with chilling clarity: “It ain’t my job to know what’s worse. It’s my job to know what is and to keep them away from what I know is terrible. I did that.” This fierce conviction, despite the horrifying nature of her act, exemplifies a certain definition of heroism—her unwavering courage to ensure her children would never suffer the ‘venomous anguish of life as an enslaved person,’ believing death to be a far preferable alternative. It is a testament to the depths of her ‘thick love.’

Beyond this singular, agonizing act, Sethe also demonstrates heroism by helping Paul D confront and heal from his own painful past. Paul D recalls ‘Her tenderness about his neck jewelry—its three wands, like attentive baby rattlers, curving two feet into the air. How she never mentioned or looked at it, so he did not have to feel the shame of being collared like a beast.’ Sethe’s quiet empathy allows Paul D to retain his manhood, a crucial aspect of his self, proving that heroism can manifest in acts of profound acceptance and understanding that help others rebuild their fractured identities. The ‘three wands’ metaphorically represent the insidious, multifaceted damage of the iron bit.

Denver’s transformation further expands the novel’s concept of heroism. Initially shy and isolated, her heroism shines through as she defies the ‘confinements of her past’ and actively works to free Sethe from Beloved’s parasitic grip. The tipping point arrives when she realizes, ‘neither Beloved nor Sethe seemed to care what the next day might bring. Denver knew it was on her. She would have to leave the yard; step off the edge of the world, leave the two behind and go ask somebody for help.’ This metaphorical ‘step[ing] off the edge of the world’ underscores her immense courage to break free from isolation and seek community aid, ultimately securing a future for herself and her mother.

Denver’s journey culminates in her assuming a powerful motherly role, inspiring Ella and a group of community women to intervene. Morrison describes their collective voices in the Clearing as a ‘wave of sound wide enough to sound deep water and knock the pods off chestnut trees,’ a powerful exorcism that cleanses Sethe. This not only highlights Denver’s crucial role but also the transformative power of a united community. Through both Sethe and Denver, Morrison emphasizes that heroism lies in the courageous intent to overcome societal preconceptions and positively influence others, resisting ideals to stand up for one’s own beliefs, thereby bringing loved ones out of the desolation of a burdensome past.

Read more about: Unlocking the Vault: A Deep Dive into Ralph Lauren’s Multi-Million Dollar Ferrari Collection and Beyond

Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’ is a literary triumph, a profound and necessary excavation of history that forces us to look unflinchingly at the devastating legacy of slavery and the extraordinary resilience of the human spirit. From the unforgettable struggles of its characters to the intricate weaving of its thematic pillars, the novel offers no easy answers, but instead invites deep contemplation on love, trauma, identity, and the very definition of freedom. It’s a powerful, enduring testament to the importance of remembering, speaking, and ultimately, healing—a book that truly remains its own ‘best thing’ and a permanent fixture in the landscape of American literature.