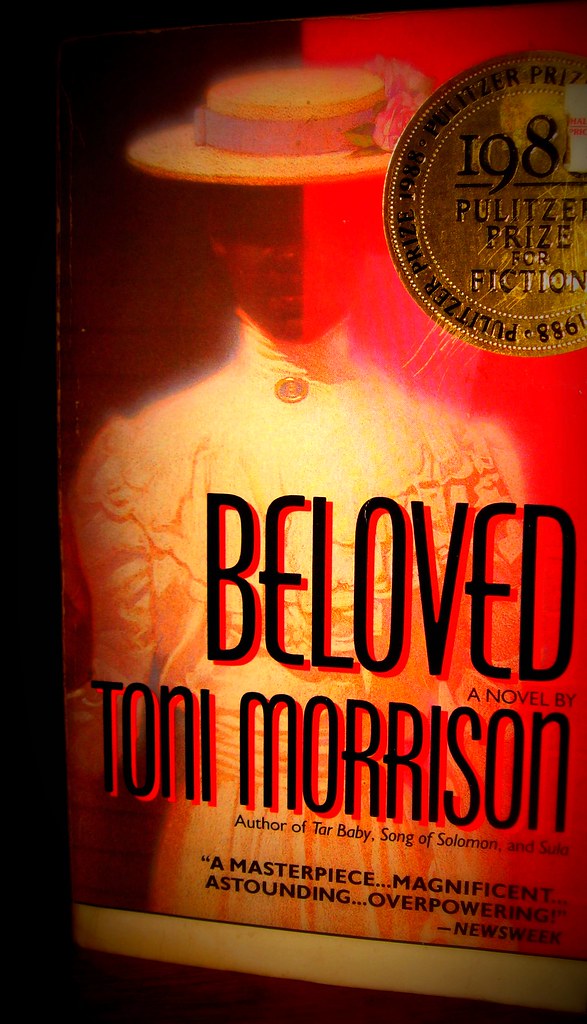

In the annals of American literature, few works resonate with the profound power and enduring impact of Toni Morrison’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, ‘Beloved.’ Published in 1987, this masterpiece plunges readers into the harrowing aftermath of slavery, exploring the deep psychological scars left on individuals and families who endured unimaginable suffering. It’s a narrative that grips the soul, demanding attention and reflection, leaving an indelible mark on its audience.

Morrison, with her unparalleled literary prowess, crafts a story that is both deeply personal and universally resonant. ‘Beloved’ is not merely a historical account; it’s a vivid, visceral exploration of memory, trauma, and the complex definition of freedom. It challenges us to confront the past, to understand the ‘rememories’ that shape the present, and to recognize the fierce, often destructive, nature of love in extreme circumstances.

This novel, acclaimed by critics and embraced by readers worldwide, is more than just a book; it’s a cultural phenomenon that has sparked countless discussions, inspired memorials, and provoked essential conversations about history and humanity. Its legacy is a testament to its raw honesty and its unflinching portrayal of the human spirit’s capacity for both immense pain and unwavering resilience. Join us as we delve into the intricate layers that make ‘Beloved’ an irreplaceable gem in the literary firmament.

1. **The Genesis of ‘Beloved’: A Haunting True Story**The profound narrative of ‘Beloved’ is rooted in a real-life tragedy, echoing the countless untold stories of those who suffered under the brutal institution of slavery. Toni Morrison dedicated her seminal work with the chilling phrase, ‘Sixty Million and more,’ a stark reference to the unfathomable number of Africans and their descendants lost to the Atlantic slave trade. This dedication immediately sets a somber, weighty tone, grounding the fiction in historical horror.

The novel’s main inspiration stems from the harrowing life of Margaret Garner, a formerly enslaved woman in Kentucky who, in 1856, made a desperate bid for freedom to Ohio. Under the draconian Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Garner faced re-enslavement. When U.S. marshals cornered her and her children, she made a heart-wrenching choice: to kill her children rather than allow them to return to the dehumanizing bondage she had known.

Morrison’s encounter with this tragic account was through an 1856 newspaper article titled ‘A Visit to the Slave Mother who Killed Her Child.’ This article was later reproduced in ‘The Black Book,’ an anthology of Black history and culture that Morrison herself edited in 1974. The raw, desperate act of a mother choosing death over slavery for her child became the emotional and thematic cornerstone of ‘Beloved,’ lending it an unparalleled authenticity and emotional depth.

This historical foundation transforms ‘Beloved’ from a mere story into a powerful act of memorialization. Morrison effectively created the ‘suitable memorial or plaque or wreath or wall or park or skyscraper lobby’ that she believed was missing for those lost to slavery. The novel itself serves as a bench by the road, a place for remembrance and reflection on the immense human cost of slavery, ensuring that Margaret Garner’s story, and those like hers, would never be forgotten.

Read more about: Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’: Unveiling the Unseen Trauma of Slavery and its Enduring Echoes

2. **The Heart of the Narrative: A Gripping Plot Unveiled**’Beloved’ opens in 1873, in a deeply haunted house at 124 Bluestone Road in Cincinnati, Ohio. Here, Sethe, a formerly enslaved woman, lives with her 18-year-old daughter, Denver. The ghost of Sethe’s eldest daughter, whom they believe to be a ‘malevolent spirit,’ has driven away Sethe’s sons, Howard and Buglar, and contributed to the isolation that envelops the remaining family members. Denver, friendless and housebound, finds solace only in the spectral presence, making her fiercely protective of it.

The fragile ecosystem of 124 is disrupted by the arrival of Paul D, one of the few surviving enslaved men from Sweet Home, the brutal plantation where Sethe, her husband Halle, and his mother Baby Suggs once lived. Paul D’s arrival brings a momentary sense of hope and normalcy, as he attempts to drive out the haunting spirit. His presence even persuades Sethe and Denver to venture out for the first time in years, attending a carnival – a rare glimpse of joy and communal life.

However, upon their return, a mysterious young woman appears on their doorstep, soaking wet, calling herself Beloved. Paul D is immediately suspicious, but Sethe, charmed, ignores his warnings. Denver, yearning for companionship, quickly grows attached to Beloved, nurturing her sickly state and coming to believe she is her older sister, miraculously returned. Beloved’s presence brings an unsettling shift, driving Paul D to increasing discomfort and eventually leading to a dark, sexually charged encounter that fills his mind with horrific memories of his own past trauma in a chain gang.

The facade of new beginnings shatters when Paul D learns the truth about Sethe’s past through a newspaper clipping shown to him by Stamp Paid. Sethe confesses that after escaping Sweet Home, four horsemen arrived to reclaim her and her children. In a desperate act to spare them from the horrors of re-enslavement, she attempted to kill them all, succeeding only with her eldest daughter. This revelation, and Sethe’s unyielding belief that her ‘thick love’ was righteous, drives Paul D away, accusing her of having ‘two feet, not four.’

Consumed by guilt and a desperate longing for redemption, Sethe becomes convinced that Beloved is her murdered child. She showers Beloved with all her time and money, attempting to explain her actions and secure Beloved’s affection, losing her job in the process. Beloved, meanwhile, becomes increasingly demanding and monstrous, literally growing larger and eventually appearing pregnant, symbolizing the past’s insatiable consumption of Sethe’s present. This spiral into obsession isolates Sethe further, as her and Beloved’s voices merge, blurring their identities and leaving Denver terrified, prompting her courageous decision to seek help from the wider Black community.

3. **Sethe: The Protagonist Defined by Unthinkable Choices**Sethe emerges as the undeniable protagonist of ‘Beloved,’ a woman indelibly shaped by the unspeakable trauma of slavery at the Sweet Home plantation. Her existence at 124 Bluestone Road is a constant battle between the present and a past that refuses to stay buried. She is a figure of immense resilience, yet one whose actions are often dictated by the deep, unhealed wounds she carries, both visible and invisible.

Her physical scars, a brutal lashing that leaves ‘a tree on her back,’ serve as a constant, painful reminder of her dehumanization. These scars are not just physical; they are symbolic of the psychological burden she bears, a constant ‘rememory’ of her time as property. This trauma fuels her most defining characteristic: a fierce, almost fanatical, maternal instinct to protect her children from ever experiencing the abuses she endured.

Sethe’s love for her children is so profound, so absolute, that it transcends conventional morality, leading her to make the ultimate, unthinkable choice. Faced with the prospect of her children being returned to Sweet Home, she attempts infanticide, believing death to be a superior fate to slavery. Her unwavering justification, ‘It ain’t my job to know what’s worse. It’s my job to know what is and to keep them away from what I know is terrible. I did that,’ underscores the agonizing moral landscape forced upon enslaved mothers.

This ‘thick love,’ as Paul D describes it, is a complex mix of devotion and destruction. It isolates her from the community and her surviving children, yet it is also a testament to her profound agency in a system designed to strip her of it. Her character embodies the devastating consequences of slavery on motherhood, where the very act of protecting one’s offspring could lead to their demise, all in the desperate hope of securing a freedom she herself barely knew.

Ultimately, Sethe’s journey is one of struggling with and eventually confronting her repressed past. Her connection with Beloved, while initially a source of renewed hope, becomes a parasitic relationship that threatens to consume her entirely. Only through the intervention of Denver and the community, and the subsequent exorcism of Beloved, can Sethe begin the painful process of individuation and accept a relationship that is truly ‘for her’ with Paul D, free from the destructive grip of her maternal guilt and trauma.

4. **Beloved: The Enigmatic Figure and Catalyst for Memory**The character of Beloved is central to the novel’s profound mystery and its exploration of trauma. She emerges mysteriously, soaking wet, from a body of water near Sethe’s house, found on the doorstep by Sethe, Paul D, and Denver after their rare outing to the fair. Her sudden appearance coincides with the cessation of the haunting at 124 Bluestone Road, leading many to believe she is the corporeal manifestation of Sethe’s murdered infant daughter.

The ambiguity surrounding Beloved’s true identity is deliberate and crucial to the novel’s power. While Morrison herself stated that Beloved is indeed the daughter Sethe killed, the narrative subtly allows for other interpretations, such as Elizabeth B. House’s theory of mistaken identity. Regardless, her name itself is laden with meaning, derived from the single word Sethe could afford to have engraved on her baby’s tombstone: ‘Beloved,’ a poignant marker of a life tragically cut short.

Beloved functions as a powerful, unsettling catalyst, forcing Sethe, Paul D, and Denver to confront their deeply buried and repressed memories of the past. Her childlike behavior, combined with an ancient wisdom, allows her to probe the raw wounds of their individual and collective histories. She is the embodiment of the unaddressed trauma, a spectral presence made flesh, demanding acknowledgment and remembrance from those who have tried so desperately to forget.

As the story progresses, Beloved’s presence becomes increasingly demanding and destructive. She manipulates Sethe’s guilt, monopolizing her time, money, and emotional energy. Her tantrums and insatiable needs mirror the consuming nature of unaddressed trauma. She literally grows in size, eventually taking the form of a pregnant woman, symbolizing the growing, overwhelming burden of the past that Sethe is attempting to atone for.

Her insidious influence eventually depletes Sethe, leaving her physically and mentally diminished, transforming her into a child-like figure while Beloved assumes a maternal role. This reversal of power illustrates how unprocessed grief and guilt can consume an individual, blurring identities and threatening to erase the self. Beloved is not just a character; she is a powerful metaphor for the inescapable, haunting presence of slavery’s legacy, demanding its story be told and its pain acknowledged.

Read more about: Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’: Unveiling the Unseen Trauma of Slavery and its Enduring Echoes

5. **Paul D: The Burden of Masculinity and Survival**Paul D Garner, one of the few men to survive the brutal Sweet Home plantation, carries the profound weight of his past. He is introduced as a wanderer, having moved continuously since his enslavement, a testament to his persistent struggle for freedom and a place to belong. His retention of the name ‘Paul D’ – a common designation for enslaved men at Sweet Home – symbolizes his fragmented identity and the lingering shadows of his past.

His emotional repression is vividly depicted through the metaphor of his ‘tobacco tin’ heart, a place where he metaphorically seals away his most painful memories from the chain gang, including the sexual violence inflicted upon him and other enslaved men. This coping mechanism, while allowing him to survive, also prevents him from fully connecting with others and processing his trauma. Beloved’s arrival, however, forces this ‘tin’ open, unleashing a flood of repressed horrors.

Paul D’s reunion with Sethe sparks a fragile hope for a new beginning, a chance to forge a family and a future. He offers a semblance of stability and romance to Sethe’s haunted existence, even acting in a fatherly manner towards Denver. Yet, he is the first to be suspicious of Beloved, recognizing her unsettling influence and feeling increasingly uncomfortable in the house that she has overtaken, intuitively sensing the danger she poses to their nascent peace.

The novel profoundly explores the definition of manhood through Paul D’s experiences. Slavery, and the subsequent Jim Crow laws, systematically stripped Black men of their dignity, their ability to protect their families, and their capacity to achieve their dreams. Paul D’s struggle to reclaim his ‘maleness’ in a society that continually dehumanizes him is a central theme. Scholar Zakiyyah Iman Jackson notes how his reduced manhood emerges in relation to a discourse of animality, reflecting the white culture’s perception of enslaved individuals.

His journey is one of rediscovering his self-worth and purpose. Sethe’s ability to see past his scars, ‘never mention[ing] or look[ing]’ at the ‘neck jewelry’ (the iron bit) that marked him ‘like a beast,’ is crucial to his healing. It allows him to retain his manhood, forming the basis of his character. By the novel’s end, Paul D’s return to a devastated Sethe and his assertion that ‘You your best thing’ signifies a monumental step towards collective healing, offering a path to rebuild not just a relationship, but also their shattered identities, recognizing the potential for self-love and a future beyond the shadows of Sweet Home.

6. **Denver: From Isolation to Independence**Denver’s journey in ‘Beloved’ is a remarkable arc from profound isolation to courageous independence, ultimately playing a pivotal role in her family’s healing. At the novel’s outset, she is an 18-year-old, shy, friendless, and housebound, confined to 124 Bluestone Road. Her only companion, ironically, is the spectral presence of her older sister’s ghost, whom she fiercely protects, a testament to her desperate longing for connection in a world that has largely shunned her.

The arrival of Beloved marks a significant turning point for Denver, initially offering the companionship she so desperately craved. She eagerly cares for the sickly young woman, quickly believing her to be her older sister miraculously returned. This bond, though initially a source of comfort and purpose for Denver, slowly begins to reveal its unsettling, darker dimensions as Beloved’s influence over Sethe becomes increasingly manipulative and destructive, transforming her mother into a shadow of her former self.

Denver witnesses her mother’s gradual decline, observing Sethe becoming “more like a child” while Beloved “seems more like the mother.” This reversal of roles, coupled with the alarming, monstrous nature of Beloved’s demands, fills Denver with a profound fear. She grasps the terrifying reality that Beloved’s parasitic presence is consuming Sethe entirely, threatening to erase her mother’s identity and livelihood. It’s a moment of terrifying clarity for the young woman, demanding action.

This critical juncture forces Denver to confront her long-held fears and break free from the confines of 124. She realizes that “neither Beloved nor Sethe seemed to care what the next day might bring. Denver knew it was on her. She would have to leave the yard; step off the edge of the world, leave the two behind and go ask somebody for help” (286). This pivotal decision, to “step off the edge of the world,” symbolizes her courageous leap into the unknown, leaving behind her isolated existence to seek aid from the very Black community from whom they had been estranged.

Denver’s brave act of reaching out to the community galvanizes the local women, leading to the collective exorcism of Beloved and, crucially, her own emergence as an independent individual. She secures a job from Mr. Bodwin, the white landlord, transforming into a working member of the community. Her journey from a secluded, fearful girl to a self-sufficient woman seeking help for her family underscores a powerful narrative of growth, resilience, and the ultimate triumph of agency over the isolating grip of trauma.

7. **The Profound Weight of Mother-Daughter Relationships**Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’ offers a harrowing yet deeply insightful exploration of mother-daughter relationships, particularly as they are distorted and tested by the brutal institution of slavery. The novel profoundly illustrates how the maternal bonds, meant to nurture and protect, can become sources of immense pain and even self-destruction when forced into an impossible moral landscape, leaving devastating consequences for both mothers and their children.

Sethe’s ‘dangerous maternal passion,’ born from the unspeakable horrors of Sweet Home, leads her to the ultimate, unthinkable act of infanticide. Her desperate attempt to save her children from re-enslavement, while rooted in a fierce love, ultimately results in the death of one daughter and the estrangement of her surviving daughter, Denver, from the Black community. This ‘thick love,’ as Paul D calls it, reveals how slavery perverted the very essence of motherhood, forcing mothers into choices that defied conventional morality, yet were driven by a profound desire to protect their offspring from a fate worse than death.

The narrative also contrasts Sethe’s approach with that of her mother-in-law, Baby Suggs, who dealt with the repeated loss of her children by “refusing to become close with her children and remembering what she could of them.” Sethe, conversely, desperately tried to hold onto and fight for her children, even to the point of killing them so they could be free. The trauma of having her milk stolen, preventing her from forming the symbolic bond of feeding her daughter, further underscores the deep wounds inflicted upon Black mothers by slavery, disrupting natural connections and inflicting lasting psychological damage.

Denver’s own development is deeply intertwined with these complex maternal dynamics. Initially isolated and dependent, first on the ghost of her sister and then on the physical manifestation of Beloved, she struggles with her relationship with Sethe. Her fear of her mother, stemming from Sethe’s past act of infanticide, is a constant undercurrent. However, as Beloved’s destructive influence intensifies, Denver’s fear evolves into a protective instinct, compelling her to act in her mother’s defense and seek external help.

Ultimately, Sethe’s journey towards individuation is catalyzed by Beloved’s exorcism. Only when freed from the consuming guilt of her maternal bond with the departed Beloved can she begin to heal and “fully accept the first relationship that is completely ‘for her,’ her relationship with Paul D.” This signifies a powerful resolution, relieving her “from the self-destruction she was causing based on her maternal bonds with her children,” allowing for a healthier, more authentic self to emerge, unburdened by the crushing weight of a past defined by forced, tragic choices.

Read more about: Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’: Unveiling the Unseen Trauma of Slavery and its Enduring Echoes

8. **The Psychological Scars of Slavery: A Fragmented Self**Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’ masterfully excavates the devastating psychological scars left by slavery, presenting a compelling portrait of individuals whose very selves have been fragmented by unspeakable trauma. A central theme is the attempt by former slaves to repress and dissociate from their painful memories, a coping mechanism that ultimately leads to a “fragmentation of the self and a loss of true identity,” a profound and debilitating internal rupture.

Sethe, Paul D, and Denver all bear the indelible marks of this psychological fracturing, each struggling to reconcile their pasts with their present identities. Beloved, the enigmatic figure, serves as a powerful, unsettling catalyst in this process. Her presence actively reminds these characters of their deeply buried and repressed memories, forcing them to confront the horrors they have tried so desperately to forget, eventually leading them, albeit painfully, toward the “reintegration of their selves.”

Slavery, the novel powerfully argues, splits a person into a “fragmented figure,” reducing them to a “self that is no self” – an identity defined by painful memories, denied and kept at bay. The path to healing and humanization requires constituting this fractured self in language, reorganizing the traumatic events, and bravely retelling those painful memories. Many characters, like Sethe, Paul D, and Baby Suggs, initially fall short of this realization, attempting to keep their pasts “at bay,” thereby preventing their own remaking.

Paul D’s ‘tobacco tin’ heart vividly symbolizes this repression. He seals away his most horrific experiences, including the sexual violence he endured in a chain gang, in this metaphorical tin. However, Beloved’s arrival forces this tin open, unleashing a flood of repressed horrors that he can no longer contain. Sethe, too, carries physical and psychological scars, notably the ‘tree on her back’ from a brutal lashing, a constant ‘rememory’ of her dehumanization that defines much of her reactive behavior.

The novel suggests that the barrier preventing the remaking of the self is the persistent desire for an “uncomplicated past” and the paralyzing fear that remembering will lead them to “a place they couldn’t get back from.” However, it is through the courageous, often agonizing, process of acknowledging and articulating these past traumas, spurred by Beloved’s haunting presence, that the characters can begin the arduous journey of healing, forging a more integrated identity that embraces, rather than represses, their complex history.

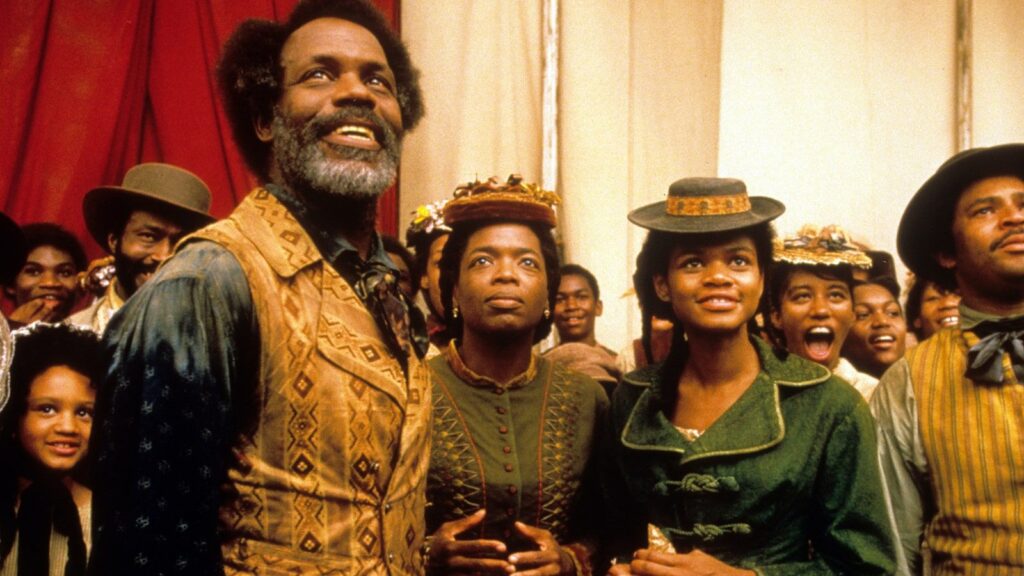

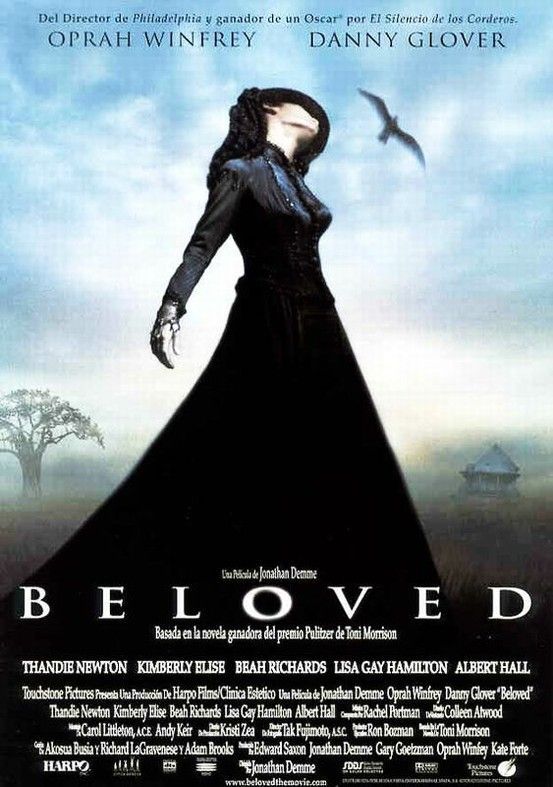

9. **’Beloved’ Beyond the Pages: Adaptations and Tributes**Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’ is not merely a novel; it’s a cultural touchstone whose profound impact resonates far beyond its pages, inspiring significant adaptations and lasting tributes that ensure its powerful message reaches a wider audience. The novel’s enduring relevance and its gripping narrative have made it a natural fit for various forms of artistic expression, further cementing its place in the popular imagination and historical consciousness.

One of the most notable adaptations came in 1998, when ‘Beloved’ was brought to the big screen. The film, directed by Jonathan Demme, was famously produced by and starred the iconic Oprah Winfrey. This adaptation introduced the harrowing story and its powerful themes to a vast new audience, leveraging the star power of Winfrey to highlight the critical importance of Morrison’s narrative and the historical trauma it addresses, bringing the painful ‘rememories’ to life visually.

Beyond the cinematic realm, ‘Beloved’ also found a voice in radio, demonstrating its versatility across different mediums. In January 2016, BBC Radio 4 broadcast a 10-episode adaptation as part of its ’15 Minute Drama’ program. Adapted by Patricia Cumper, this radio series allowed the intricate narrative and its profound emotional depth to be experienced through sound, further expanding the novel’s reach and engaging listeners in a different, equally immersive way, showcasing its timeless appeal.

Perhaps one of the most poignant tributes inspired by ‘Beloved’ is the “bench by the road” initiative. This concept originated from Toni Morrison herself, who, upon accepting the Frederic G. Melcher Book Award on October 12, 1988, lamented the absence of a “suitable memorial or plaque or wreath or wall or park or skyscraper lobby” honoring the “Sixty Million and more” Africans and their descendants lost to the Atlantic slave trade. She famously stated, “And because such a place doesn’t exist (that I know of), the book had to.”

Inspired by her powerful remarks, the Toni Morrison Society embarked on a mission to install these symbolic “benches by the road” at significant sites in the history of slavery in America. The very first bench was dedicated on July 26, 2008, on Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina, a poignant location as it was the entry point for approximately 40% of enslaved Africans brought to the United States. Morrison expressed how “extremely moved” she was by this memorial. In 2017, the 21st such bench was placed at the Library of Congress, dedicated to Daniel Alexander Payne Murray, the first African-American assistant librarian of Congress, ensuring that the legacy of those lost and forgotten would always have a place for remembrance and reflection.

10. **Critical Acclaim and Enduring Controversy: The Novel’s Legacy**Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’ has carved an unshakeable place in American literature, marked by both immense critical acclaim and enduring controversy, solidifying its legacy as a vital, often challenging, masterpiece. Upon its publication in 1987, the novel swiftly garnered widespread recognition, ultimately winning the prestigious Pulitzer Prize for Fiction a year later, in 1988. It was also a finalist for the National Book Award in 1987, signaling its immediate impact on the literary world.

The depth of its influence was further highlighted when a survey of writers and literary critics compiled by The New York Times ranked ‘Beloved’ as the best work of American fiction from 1981 to 2006. This extraordinary accolade underscores its profound and lasting resonance, confirming its status not just as a significant novel of its time, but as a pivotal work in the broader landscape of modern American literature, continually sparking discussions and shaping literary discourse.

However, its journey to universal acceptance was not without its moments of contention. When ‘Beloved’ did not win the National Book Award, a powerful protest erupted, with 48 African-American writers and critics, including luminaries like Maya Angelou and Henry Louis Gates Jr., signing a letter published in The New York Times Book Review on January 24, 1988. This collective voice passionately advocated for the novel’s significance, underscoring its cultural and literary importance, which was subsequently recognized with multiple other awards, including the Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Book Award, the Melcher Book Award, the Lyndhurst Foundation Award, and the Elmer Holmes Bobst Award.

Scholarly debate has also been a hallmark of ‘Beloved’s’ legacy, particularly concerning the enigmatic character of Beloved herself. Critics have grappled with whether she is a literal ghost, a supernatural incarnation of Sethe’s murdered daughter, or, as Elizabeth B. House argued, a real person in a case of “mistaken identity,” where an escaped woman, haunted by her own losses, comes to believe Sethe is her mother. This ambiguity fuels the novel’s rich interpretive possibilities, further deepening its exploration of memory, trauma, and familial ties, and prompting readers to actively engage with its layered meanings.

Despite its critical triumph, ‘Beloved’ has faced significant challenges, including being banned in many U.S. schools. Common reasons for censorship often cite “sexually explicit content,” including instances of “bestiality, infanticide, sex, and violence,” highlighting the novel’s unflinching portrayal of slavery’s brutal realities. A notable controversy arose in Virginia, where parental concern about the book’s content inspired the ‘Beloved Bill,’ legislation that would have mandated parental notification for “sexually explicit content” and offered alternative assignments. Although vetoed by Governor Terry McAuliffe, the debate surrounding the book’s inclusion in curricula continues to reflect ongoing societal tensions over education and difficult historical narratives.

Ultimately, ‘Beloved’s’ enduring legacy is a complex tapestry woven from its literary brilliance, its unflinching engagement with historical trauma, and its capacity to provoke vital conversations. Its inclusion on the BBC News’ list of the “100 most inspiring novels” in 2019 speaks volumes about its power to move and challenge readers across generations. It stands as a timeless masterpiece, continually pushing boundaries, demanding remembrance, and affirming the profound importance of confronting uncomfortable truths to understand the depths of human experience and resilience.

As we reflect on the multifaceted brilliance of ‘Beloved,’ it becomes clear that Toni Morrison’s masterpiece transcends the boundaries of a mere story. It is a profound meditation on the human spirit’s capacity for survival, for love, and for the arduous journey of healing from unimaginable wounds. The intricate layers of its characters, themes, and historical context continue to challenge and inspire, cementing its place as a crucial work that reminds us of the power of literature to confront the past, understand the present, and shape a more empathetic future. Its legacy is not just in its awards or adaptations, but in the countless lives it has touched, forcing us to remember and, ultimately, to heal.