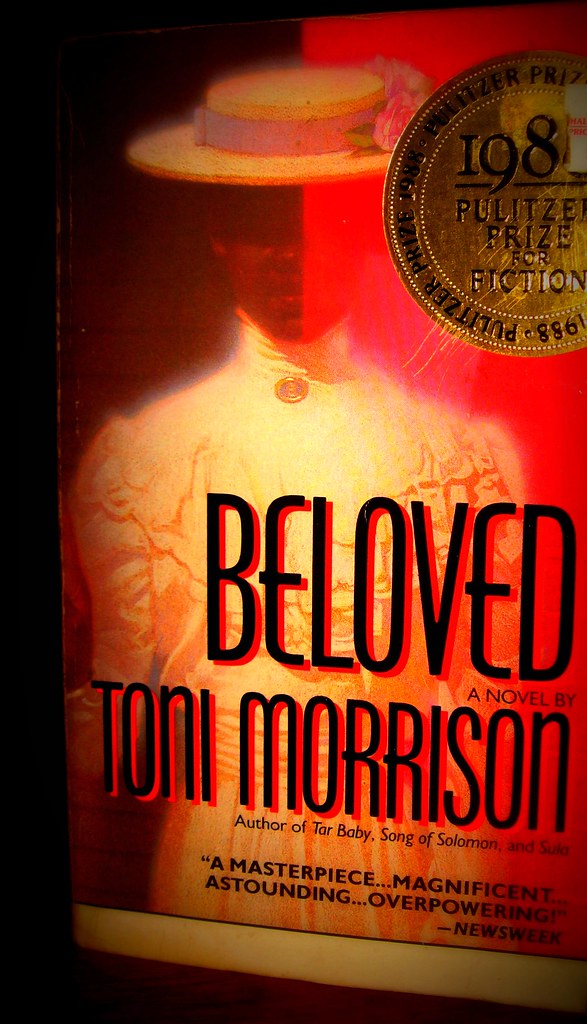

Toni Morrison’s 1987 novel, *Beloved*, isn’t just a book; it’s an experience, a journey into the darkest corners of American history and the human spirit’s astonishing resilience. This Pulitzer Prize-winning masterpiece, set in the tumultuous period after the American Civil War, continues to resonate deeply with readers, exploring themes of love, loss, memory, and the enduring psychological scars of slavery. It’s a story that forces us to confront uncomfortable truths, but ultimately, it’s also a testament to the power of community and the possibility of healing.

What makes *Beloved* so utterly compelling is its ability to transform historical trauma into a living, breathing narrative that feels both deeply personal and universally significant. Morrison masterfully weaves together the past and present, blurring the lines between memory and reality, making the novel a powerful meditation on how the past continues to shape us. From its unforgettable characters to its profound exploration of systemic injustice, this novel challenges readers to look closer, to feel more deeply, and to remember what society often tries to forget.

So, grab a cozy blanket and settle in, because we’re about to embark on a deep dive into the heart of *Beloved*. We’ll unravel its intricate plot, explore the powerful character arcs, and shine a light on why this novel remains such a vital and inspiring piece of literature today. Get ready to discover the layers that make this story a timeless classic.

1. **The Haunting Premise: Margaret Garner’s Story**

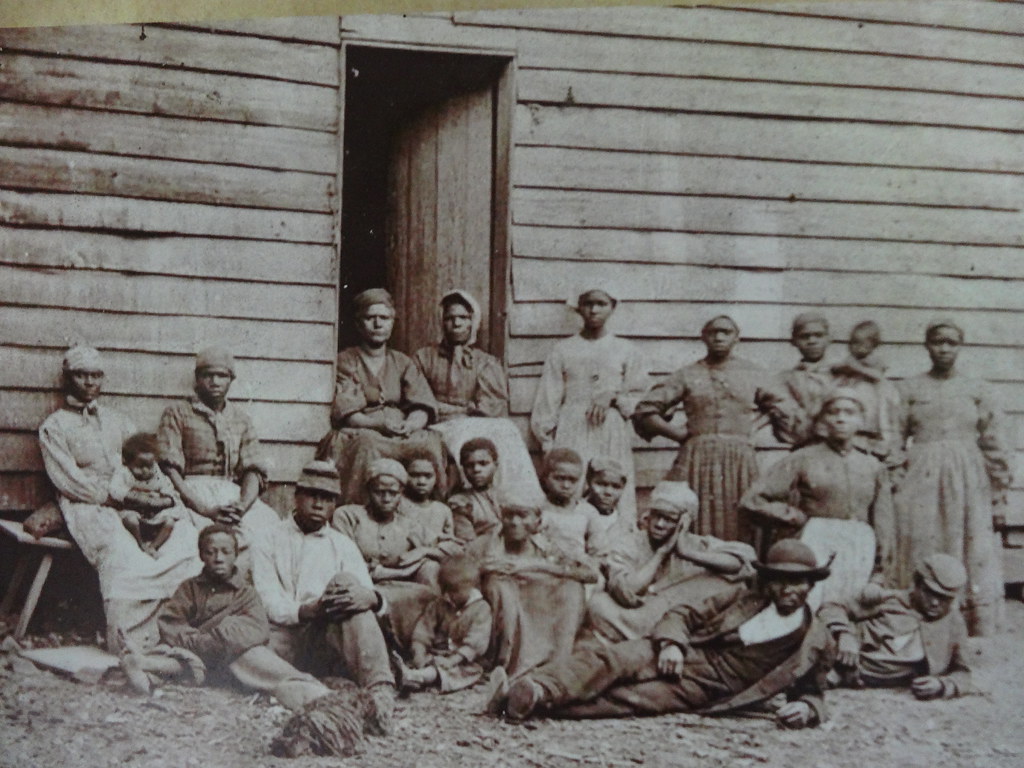

At the very core of *Beloved*’s raw emotional power is a real-life horror story that Morrison meticulously researched. The narrative derives directly from the life of Margaret Garner, an enslaved woman in Kentucky who, in 1856, made a desperate escape to the free state of Ohio. Her story is one that immediately grips you, showcasing the unimaginable choices forced upon individuals by the brutal institution of slavery. It’s a chilling reminder of the lengths to which a mother would go to protect her children from a fate worse than death.

Garner’s harrowing tale reached a tragic climax when, subject to capture under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, U.S. marshals broke into the cabin where she and her children had barricaded themselves. In a moment of sheer desperation and terrifying love, she was attempting to kill her children. She had already succeeded in killing her youngest daughter, all in the hopes of sparing them from being returned to the crushing indignity and terror of slavery. This act, born of a mother’s ultimate fear, forms the visceral heart of Morrison’s fictionalized narrative, challenging our understanding of right and wrong under extreme duress.

Morrison’s main inspiration for the novel wasn’t just a fleeting thought; it was a profound connection to an account titled “A Visit to the Slave Mother who Killed Her Child.” This powerful article, initially published in an 1856 newspaper called the *American Baptist*, was later reproduced in *The Black Book*. This anthology of texts on Black history and culture, which Morrison herself had edited in 1974, provided her with the authentic, painful foundation for *Beloved*. It demonstrates her dedication to bringing marginalized histories to the forefront, giving voice to those who were silenced.

This historical incident isn’t just a footnote; it’s the very genesis of *Beloved*, grounding the fantastical elements of the haunting in a brutally real past. By rooting her story in Margaret Garner’s unimaginable choice, Morrison immediately imbues the novel with a historical weight and moral complexity that demands deep reflection. It forces us to confront the true cost of slavery, not just in terms of physical bondage, but in the psychological and emotional devastation it wreaked upon families.

2. **Sethe: A Mother’s Desperate Love and Its Consequences**

Meet Sethe, the unforgettable protagonist of *Beloved*, a formerly enslaved woman who carries the unbearable weight of her past. She escaped the notorious Sweet Home plantation, but her freedom is far from peaceful, as her Cincinnati home at 124 Bluestone Road is haunted by what she believes is the ghost of her eldest daughter. Sethe’s character is defined by a fierce, almost dangerous, maternal passion, born from the unspeakable traumas she endured and a desperate need to protect her children from repeating her own painful experiences.

Sethe’s love, famously described as “too thick” by Paul D, leads her to the horrific act of infanticide. She believes that by killing her children, she is “trying to put my babies where they would be safe,” sparing them from the return to the brutal manager, Schoolteacher, and the dehumanizing life of slavery. This act, though scorned by the community, is, in Sethe’s mind, the ultimate expression of a mother’s protection. It’s a love so profound it twists into something devastating, showcasing the extreme measures one might take when all other options are stripped away.

Beyond the dramatic act, Sethe’s history is deeply etched into her physical and psychological being. She lives with “a tree on her back,” scars from being whipped, a constant, visible reminder of the violence she suffered. Her trauma extends to the deepest maternal bonds, having had her milk stolen, an act that prevented her from forming the symbolic connection with her daughter through feeding. This early violation profoundly impacts her capacity for mothering, shaping her desperate, all-consuming attachment to her children.

Initially, Sethe is isolated, living with Denver in a house shunned by the Black community due to her past actions. When Beloved, the mysterious young woman, appears, Sethe is instantly charmed, believing her to be her murdered daughter returned. This belief ignites a glimmer of hope for a complete family, but it quickly consumes her. She pours all her time and money into Beloved, losing her job and even her sense of self, becoming more like a child as Beloved grows increasingly demanding and takes on a pregnant form. Sethe’s guilt drives her to an extreme state, jeopardizing her own well-being.

However, Sethe’s journey isn’t solely one of tragedy and self-destruction. After Beloved’s eventual exorcism, Sethe is left devastated but also freed. She begins to heal, finding individuation and eventually accepting Paul D’s love, the first relationship that is truly “for her.” This final acceptance allows her to question her self-worth, asking, “Me? Me?” as she slowly learns to love herself again, breaking free from the self-destruction caused by her overwhelming maternal bonds.

Read more about: Beyond the Pages: 15 Jaw-Dropping Reasons Why Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’ Still Shakes the Literary World (and Our Hearts!)

3. **Beloved: The Enigma of the Spirit Incarnate**

Perhaps the most enigmatic and discussed character in the novel is Beloved, a young woman who appears mysteriously, soaking wet, from a body of water near Sethe’s home. She is discovered by Sethe, Paul D, and Denver upon their return from a carnival. Her arrival is unsettling, yet profoundly significant, as the haunting that plagued 124 Bluestone Road ceases with her presence. Immediately, the suspicion arises: could this be the murdered baby, returned to the land of the living?

Beloved quickly becomes a powerful catalyst, forcing the characters to confront their deeply repressed memories and traumas. For Sethe, Beloved is the daughter she killed, the baby whose tombstone could only afford the single engraved word: “BELOVED.” This naming convention itself highlights the profound lack and loss endured under slavery, where even a proper name for a lost child was a luxury. Beloved’s presence acts like an open wound, allowing the unspoken pains of the past to finally surface for Sethe, Paul D, and Denver, initiating a painful but necessary process of remembrance.

Commentators and scholars have debated the true nature of Beloved, questioning whether she is a literal ghost, a real person, or perhaps a symbolic representation of collective ancestral trauma. Elizabeth B. House proposes an intriguing interpretation: Beloved is not a ghost but a real person, and the novel presents two instances of mistaken identity. In this view, Beloved, haunted by the loss of her own African parents, comes to believe Sethe is her mother. Conversely, Sethe, longing for her dead daughter, is easily convinced that Beloved is the child she lost. This interpretation clarifies many puzzling aspects and underscores Morrison’s focus on fractured familial ties.

As the narrative progresses, Beloved’s presence at 124 becomes increasingly ominous and demanding. She throws tantrums, consumes Sethe’s resources and emotional energy, and literally grows bigger and bigger, eventually taking the form of a pregnant woman. This physical transformation mirrors Sethe’s inverse decline; Sethe becomes increasingly childlike, starving herself, while Beloved seems to draw life force from her, morphing into a maternal, yet monstrous, figure. Her insatiable demands highlight the heavy cost of unaddressed trauma and guilt.

Ultimately, Beloved’s parasitic grip on Sethe reaches a breaking point. Through Denver’s courageous outreach to the community and the collective will of the local women, Beloved is exorcised from 124. Her disappearance leaves Sethe devastated, but it also marks the beginning of her true healing. As time passes, those who knew Beloved gradually forget her, until “all traces of her are gone,” symbolizing the arduous, generational effort required to move past the profound scars of slavery without erasing its memory entirely.

4. **Paul D’s Journey: Repression, Masculinity, and Healing**

Paul D Garner, one of the enslaved men from Sweet Home, is another pivotal character whose journey embodies the psychological toll of slavery and the arduous path to self-reintegration. He carries his name from enslavement – a poignant detail reminding us of how identity was often reduced under the system. Paul D’s heart is metaphorically described as a “tobacco tin,” a tightly sealed container where he keeps his agonizing memories from Sweet Home and the horrific experiences of being forced into a chain gang. He has been constantly moving, trying to outrun his past, until he arrives at 124 Bluestone Road.

His reunion with Sethe sparks a romantic relationship, but it is far from simple. Beloved’s arrival acts as a profound disruptor, forcing Paul D to confront the very memories he had so diligently locked away. Beloved, in a deeply unsettling encounter, compels him to touch her “inside part,” and during this act, his mind is flooded with “horrific memories from his past, including the sexual violence inflicted upon him and the other men while in a chain gang.” Beloved, in essence, pries open his “tobacco tin,” releasing the torrent of pain he had repressed for years, making true healing both possible and terrifying.

Paul D’s experiences under slavery profoundly distort his sense of self and his understanding of manhood. Scholar Zakiyyah Iman Jackson notes that his “reduced manhood emerges in relation to a discourse of animality,” a dehumanizing comparison used by white slave owners. He struggles to define his masculinity in a society that stripped Black men of their dignity, dreams, and goals. He believed his sacrifices and suffering had earned him the right to achieve his desires, but racism continually denied him that fulfillment, keeping him at the “base” of society, as Stamp Paid observes him “stripped of the very maleness that enables him to caress and love the wounded Sethe.”

Despite the complexities and the initial suspension of his relationship with Sethe after discovering the truth about Beloved, Paul D eventually returns. He finds Sethe bed-ridden and devastated by Beloved’s disappearance. In a moment of profound tenderness and healing, he tells her, “Sethe, you are your own ‘best thing.'” This declaration is crucial, prompting Sethe to question her self-worth and begin to accept her own identity beyond her overwhelming maternal grief. Paul D’s return signifies a mutual journey towards reconciliation and the possibility of a shared future free from the immediate hauntings of the past.

Moreover, Sethe, through her quiet understanding, helps Paul D regain his sense of manhood. He deeply appreciates her “tenderness about his neck jewelry – its three wands, like attentive baby rattlers,” scars from the iron bit he was forced to wear. Sethe “never mentioned or looked at it, so he did not have to feel the shame of being collared like a beast.” This compassionate act allows him to retain his dignity and masculinity, fostering a connection so deep that he wishes “to put his story next to hers,” signaling a shared future built on mutual understanding and resilience.

5. **Denver’s Transformation: From Isolation to Community**

Denver, Sethe’s eighteen-year-old surviving daughter, begins *Beloved* as a deeply isolated and housebound character. Living at 124 Bluestone Road, she is friendless and shy, her only true companion being the ghost she believes haunts their home. The community’s rejection of Sethe, combined with her brothers’ flight due to their fear of the ghost, has left Denver profoundly alone, fostering a unique, almost symbiotic, relationship with her mother and the spectral presence that fills their lives.

Upon Beloved’s mysterious arrival, Denver is initially overjoyed. She eagerly cares for the sickly young woman, convinced that this is her older sister, returned from the grave. This newfound companionship breaks her isolation, giving her a sense of purpose and connection she had long lacked. For a time, Beloved represents the return of family, a hope for normalcy in their abnormal lives, and a relief from the profound loneliness that had characterized Denver’s existence.

However, Denver’s relationship with Beloved soon darkens. She begins to witness Beloved’s increasingly demonic activities and growing demands, and crucially, she starts to truly understand the depth of her mother’s past actions. She realizes that her brothers had indeed fled out of fear, a fear she now shares. As Sethe becomes more child-like under Beloved’s consuming influence, and Beloved paradoxically assumes a more mother-like, controlling role, Denver experiences a profound shift. Her childish dependence gives way to a dawning awareness of the danger threatening her mother and herself.

This realization marks Denver’s “tipping point of heroism.” She understands that “neither Beloved nor Sethe seemed to care what the next day might bring,” and that the responsibility to act falls entirely on her. She must “leave the yard; step off the edge of the world,” venturing beyond the confines of 124 to seek help from the very Black community that had shunned them for so long. This courageous act, breaking her long-standing isolation, signifies her true coming-of-age and her nascent independence.

Denver’s outreach to the community proves instrumental in saving her mother. She approaches Mr. Bodwin, their White landlord, asking for work, demonstrating her newfound agency. More significantly, her desperation and courage inspire Ella and other local women to form a collective force, a “wave of sound” that culminates in Beloved’s exorcism. Denver’s transformation from a solitary, fearful child to a protective, community-minded woman who actively fights for her mother’s wellbeing is one of the novel’s most powerful arcs, breaking the cycle of isolation and self-destruction that had plagued 124.

6. **Baby Suggs: The Preacher of Self-Love and Its Decline**

Baby Suggs, Halle’s mother and Sethe’s mother-in-law, stands as a towering figure in the novel, representing both spiritual resilience and the crushing weight of collective trauma. Her son, Halle, worked tirelessly to buy her freedom, a testament to the enduring love and sacrifice within enslaved families. Once freed, Baby Suggs travels to Cincinnati and quickly establishes herself as a deeply respected spiritual leader within the Black community, a testament to her inherent wisdom and powerful presence.

Her sermons in the “Clearing” are among the most profound and moving passages in the novel. She preaches a radical message of self-love and self-acceptance to her community, urging formerly enslaved Black people to cherish their own bodies, their hearts, and their minds, for “other people will not” love them. This message was a vital, life-affirming balm for those who had endured generations of dehumanization, a direct counter to the psychological damage inflicted by slavery. She urged them to reclaim their humanity, to find joy and beauty within themselves.

However, this hard-won respect and spiritual authority are tragically undermined. The community’s envy, sparked by Baby Suggs’s ability to turn a simple gift of food into a lavish feast, and the horror instigated by Sethe’s act of infanticide, shatter her standing. The community, unable to process the profound implications of Sethe’s choice, distances itself from 124 Bluestone Road and, by extension, from Baby Suggs. This communal rejection breaks her spirit, leading her to retire to her bed, where she spends her remaining days contemplating only “pretty colors” – a poignant escape from a world too full of ugliness and pain.

Baby Suggs’s personal history also provides a stark contrast to Sethe’s desperate maternal acts. Having lost eight children to the brutality of slavery, she developed a different coping mechanism: she “dealt with this by refusing to become close with her children and remembering what she could of them.” This painful, protective detachment stands in stark opposition to Sethe’s fierce, possessive fight for her children’s freedom, highlighting the varied and agonizing ways enslaved mothers attempted to navigate their impossible circumstances.

Although she dies at the age of 70, eight years before the novel’s main events begin, Baby Suggs’s presence is deeply felt throughout the narrative. Her legacy of radical self-love, her wisdom, and her eventual spiritual defeat resonate powerfully through the lives of Sethe, Denver, and Paul D. She embodies the profound resilience and the devastating vulnerability of a people struggling to heal from unimaginable wounds, leaving an enduring mark on the novel’s thematic landscape.

Now that we’ve navigated the intricate character journeys and the foundational narrative of *Beloved*, it’s time to plunge deeper into the profound thematic underpinnings that make this novel an enduring masterpiece. Toni Morrison doesn’t just tell a story; she constructs a universe where every detail echoes the psychological and societal scars of slavery, pushing us to rethink identity, pain, and even heroism. Get ready to explore the layers that reveal why *Beloved* continues to spark conversation and shape our understanding of history and humanity.

7. **The Psychological Scars of Slavery: Fragmentation of Self**

The suffering endured under slavery wasn’t just physical; it left indelible psychological scars, prompting most former slaves to repress these agonizing memories in a desperate attempt to forget the past. This isn’t just a minor detail; this repression and dissociation from their past selves caused a profound fragmentation of identity, leading to a crippling loss of their true self. Imagine carrying such a heavy burden that your only defense is to seal it away, often at the cost of knowing who you truly are.

Morrison brilliantly illustrates how this deep-seated repression creates a “self that is no self,” an identity denied and kept at bay, like a shadow perpetually chasing you. For characters like Sethe, Paul D, and Denver, this loss of self was a shared affliction, a collective wound that could only begin to heal when they bravely confronted and reconciled their pasts, bringing their fragmented memories and earlier identities back into focus. It’s about piecing yourself back together, one painful memory at a time.

This is where Beloved, the mysterious figure, plays an absolutely crucial, albeit unsettling, role. She isn’t just a character; she’s a catalyst, serving as a constant, unavoidable reminder of the repressed memories that haunt these characters. Her presence forces them into a painful, yet ultimately necessary, process of remembrance, initiating the long, arduous journey toward the reintegration of their shattered selves. Without her, the past might have remained buried, but so too would the possibility of true healing.

Slavery literally splits a person into a fragmented figure, where their identity, composed of painful and unspeakable memories, is denied. To truly heal and humanize oneself, a person must reconstruct this ‘unmade self’ through language, by reorganizing and retelling those agonizing events. Characters like Sethe, Paul D, and Baby Suggs initially struggle to remake themselves because they cling to a desire for an “uncomplicated past” and fear that remembering will lead them to “a place they couldn’t get back from.” The power to define the self, in this context, lies in the “word” and the audience—once the language changes, so too can the identity. It’s a powerful lesson in self-authorship, even against impossible odds.

Read more about: Unveiling the Layers of Legacy: 11 Jaw-Dropping Insights into Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved’ That Still Resonate

8. **Defining Manhood in a Dehumanizing System**

Beyond exploring emotions, *Beloved* powerfully confronts the theme of manhood and masculinity, showing how the horrors of enslavement grotesquely distort a man from his very essence. Morrison does more than just depict emotions; she accurately portrays the systematic destruction of dignity, revealing how slavery wasn’t just a physical bondage but an assault on the soul and identity, particularly for Black men.

Paul D Garner, a pivotal figure, embodies this struggle. Morrison masterfully uses his “half-formed words and thoughts” to give us a raw, intimate glimpse into his mind, showcasing his battle to define masculinity within a system designed to strip Black men of their dignity, dreams, and goals. Scholar Zakiyyah Iman Jackson highlights how Paul D’s “reduced manhood emerges in relation to a discourse of animality,” a dehumanizing comparison tragically employed by white slave owners. His journey is a testament to the crushing weight of such systemic oppression.

Paul D firmly believed that his immense sacrifices and unimaginable suffering had earned him the right to achieve his desires, that society owed him a return for his endurance. Yet, racism relentlessly denied him that fulfillment, perpetually keeping him at the “base” of society. As Stamp Paid poignantly observes him “stripped of the very maleness that enables him to caress and love the wounded Sethe,” we witness the profound impact of this societal degradation. His aspirations were constantly thwarted, leaving him perpetually striving for a recognition that was always just out of reach.

This struggle wasn’t unique to Paul D. During the Reconstruction era, and with the implementation of Jim Crow laws, Black men faced immense limitations in white-dominant society, making the establishment of a self-defined identity seem almost impossible. Many, like Paul D, grappled to find their place and achieve their goals due to the “disabilities” that confined them to the lower echelons of the social hierarchy. Morrison’s depiction of Paul D “sitting on the base of the church steps” or a “tree stub” powerfully visualizes this societal positioning, underscoring that while Black men were the foundational laborers, they were simultaneously coerced into a society that deemed them “lower-status” because of their skin color.

Read more about: Unpacking ‘Beloved’: The Profound Themes and Enduring Legacy of Toni Morrison’s Masterwork

9. **Family Bonds Broken and Remade**

Family relationships form an instrumental, deeply poignant element of *Beloved*, vividly illustrating the immense stress and systematic dismantlement of African-American families during and after the era of slavery. Under such a brutal system, enslaved people were denied fundamental rights—rights to themselves, their families, their possessions, and most agonizingly, their children. This institutionalized cruelty shattered the very fabric of familial connection.

This horrific context reframes Sethe’s desperate act of infanticide, which she perceived as a “peaceful act.” In her mind, killing her daughter was an ultimate act of salvation, saving her from the unimaginable indignity and terror of a life in slavery. Yet, this choice, born of profound love and fear, resulted in her family being divided and fragmented, a heartbreaking reflection of the brokenness and lasting trauma that plagued formerly enslaved families even after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed.

Given that enslaved people were largely excluded from mainstream societal events and institutions, many found solace and placed their faith and trust in the supernatural. They often performed rituals and prayed to their god or multiple gods, seeking spiritual connection and agency where earthly avenues were denied. This spiritual engagement becomes a critical lens through which to understand the novel’s mystical elements, particularly the haunting presence at 124 Bluestone Road.

In *Beloved*, the ghost of Sethe’s murdered daughter literally haunts her. Consider the scene where Sethe, Denver, and Paul D return from a rare social outing—a neighborhood carnival—only to find the mysterious Beloved waiting at their doorstep. Throughout the novel, Sethe firmly believes this young woman is her daughter, returned after 18 years. This deeply personal scenario powerfully illustrates how fractured family relationships are used to externalize and display the intense mental strife and trauma that the protagonist, Sethe, faces. It’s a haunting manifestation of unresolved grief and the desperate longing for connection.

Read more about: From ‘Dirt Poor’ to Diamond Rings: 14 Celebs Who Proved Hard Work (Not Nepotism) Paved Their Way to Stardom

10. **The Many Faces of Pain: From Scars to ‘Rememories’**

The pain woven throughout *Beloved* is undeniably universal, scarring every individual touched by slavery in profound ways—physically, mentally, sociologically, and psychologically. What’s truly striking is how some characters, almost as a coping mechanism, tend to “romanticize” their pain, transforming each agonizing experience into a pivotal turning point in their lives. This intricate concept resonates with historical themes found in early Christian contemplative tradition and the African-American blues tradition, where suffering often became a source of profound expression.

Indeed, *Beloved* is a powerful testament to the systematic torture that formerly enslaved people continued to endure even after the Emancipation Proclamation. The narrative itself often feels like a “complex labyrinth” because the characters have been “stripped away” from their voices, their narratives, and their very language, leading to a diminished sense of self. Each character’s story, distinct from the others, reveals their unique and harrowing experiences with slavery, painting a mosaic of individual and collective trauma.

Adding another layer to this is the way many major characters attempt to “beautify” pain, subtly diminishing the horrors they’ve faced. A poignant example is Sethe repeatedly recounting what a White girl said about her whip scars, describing them as “a Choke-cherry tree. Trunk, branches, and even leaves.” She offers this description to everyone, perhaps in an unconscious effort to find beauty in her extreme pain, even as Paul D and Baby Suggs recoil in disgust, refusing to validate such a painful aesthetic. Their reactions highlight the deep division in how trauma can be perceived and processed.

Sethe extends this complex relationship with pain to Beloved herself. The memory of her ghost-like daughter becomes a potent mix of memory, grief, and spite that both connects and separates Sethe from her lost child. For instance, despite Paul D and Baby Suggs subtly suggesting Beloved is unwelcome, Sethe insists on her presence in their home—a place of vulnerability and heart. She sees Beloved, “all grown and alive,” rather than the searing pain of her murder, illustrating her desperate need to overwrite the past. Ultimately, as Beloved fades, Paul D gently encourages Sethe to love herself instead, beginning a new chapter of healing. This journey through pain is profoundly shaped by what Sethe calls “rememory,” a concept central to the novel’s exploration of how the past continues to live, breath, and haunt in the present.

11. **Heroism Reimagined: Courage in the Face of Opposition**

In *Beloved*, heroism isn’t presented as an absolute ideal, but rather as a concept relative to individual past experiences and the profound influence of community. The literary characterization of both Sethe and Denver serves as a powerful testament to this nuanced definition, showing us that courage takes many forms, often born from the most unexpected places and against the fiercest opposition.

Morrison deliberately develops Sethe not as a conventional hero, but as an individual whose capacity for enabling others to break free from the shackles of the past redefines heroism. Sethe’s harrowing decision to kill her own child, Beloved, is widely condemned by the community, yet she never wavers in her conviction. As she powerfully justifies, “It ain’t my job to know what’s worse. It’s my job to know what is and to keep them away from what I know is terrible. I did that.” She directly confronts society’s expectations, choosing death over the venomous anguish of slavery for her children, an act she believes is the ultimate path to their complete safety.

Beyond her defining act, Sethe also demonstrates heroism by profoundly helping Paul D deal with his own agonizing past. Near the end of the novel, Paul D reflects on “Her tenderness about his neck jewelry — its three wands, like attentive baby rattlers, curving two feet into the air. How she never mentioned or looked at it, so he did not have to feel the shame of being collared like a beast. Only this woman Sethe could have left him his manhood like that. He wants to put his story next to hers.” This compassionate act, acknowledging his trauma without shaming him, allows Paul D to reclaim a vital piece of his identity and masculinity that slavery had stripped away, making Sethe a quiet, yet formidable, hero in his personal healing.

Then there’s Denver, who defies the confinements of her past, making her own heroic leap to help Sethe escape Beloved’s parasitic grip—a hold that threatened to consume her mother’s life and any hope for a future. Feeling trapped by her isolation at 124 Bluestone Road, Denver faces the monumental challenge of leaving the only world she knows. Her “tipping point of heroism” arrives when she realizes, “neither Beloved nor Sethe seemed to care what the next day might bring. Denver knew it was on her. She would have to leave the yard; step off the edge of the world, leave the two behind and go ask somebody for help.” This metaphorical “step off the edge of the world” beautifully captures her courage to break her isolation and seek aid from the very community that had shunned them.

Denver’s courageous outreach doesn’t just save her mother; it inspires Ella and other local women to form a “wave of sound” that culminates in Beloved’s powerful exorcism. Morrison vividly describes this collective force as being able to “knock the pods off chestnut trees,” highlighting the immense power of a united community. Through Denver’s transformation from a solitary child to a protective, community-minded woman, Morrison champions the idea that heroism lies in the courageous intent to overcome societal preconceptions, inspire others, and fight for the greater good, thereby bringing loved ones out of the desolation of their past burdens toward a foreseeable future.

12. **The Enduring Legacy and Controversies**

Published in 1987, *Beloved* immediately garnered immense critical acclaim, marking a new height for Toni Morrison’s career. Although it was a finalist for the National Book Award, its initial loss sparked a powerful protest: 48 African-American writers and critics, including luminaries like Maya Angelou and Angela Davis, signed a letter of protest published in *The New York Times Book Review*. However, the following year, *Beloved* triumphantly received the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, along with a host of other prestigious awards, cementing its place in literary history.

The novel is widely celebrated as a profound exploration of complex themes: the deep bonds of family, the pervasive nature of trauma, the repression of memory, and the crucial work of restoring the historical record to give voice to the collective memory of African Americans. Morrison herself, and many critics, have pointed to the controversial epigraph, “60 million and more,” as a stark reference to the estimated African lives lost during the brutal Atlantic slave trade, underscoring the novel’s powerful historical and social context.

Scholars have tirelessly debated the enigmatic nature of Beloved, questioning whether she is a literal ghost or a real person. While many initial reviewers faulted *Beloved* as a confusing ghost story, Elizabeth B. House offered an intriguing counter-argument: Beloved is not a ghost, but rather the novel presents two instances of mistaken identity. In this view, Beloved, haunted by the loss of her own African parents, comes to believe Sethe is her mother, while Sethe, longing for her dead daughter, is easily convinced Beloved is the child she lost. This interpretation, House contends, clarifies many puzzling aspects and underscores Morrison’s central concern with fractured familial ties.

Morrison’s work, particularly *Beloved*, is also hailed for its profound impact on African-American literature, acting as a powerful means of healing and recovery. Critics like Timothy Powell argue that Morrison’s narrative “rewrites blackness as ‘affirmation, presence, and good’,” while Theodore O. Mason Jr. suggests her stories actively “unite communities.” Many scholars explore memory—or what Sethe calls “rememory”—through a psychoanalytic lens, with Ashraf H. A. Rushdy noting how primal scenes offer “an opportunity and affective agency for self-discovery.” Yet, as Jill Matus warns, Morrison’s representations of trauma are “never simply curative”; they also provoke readers to vicarious experience, serving as a means of transmission for past pains.

Beyond its critical reception, *Beloved* continues to inspire and resonate deeply. It earned a spot on the BBC News’s list of the 100 most inspiring novels in 2019, but its powerful content has also made it a frequent target for banning in U.S. schools, with common reasons citing bestiality, infanticide, sex, and violence. It even sparked a legislative debate in Virginia, leading to the “Beloved Bill” which would have required parental notification of “sexually explicit content.” This ongoing dialogue, whether in accolades or controversies, vividly demonstrates the novel’s enduring, undeniable impact, perpetually challenging readers to confront uncomfortable truths and engage with its vital legacy.

Read more about: The Unraveling Value: 12 Restaurant Chains Where Diners Say the Price Just Isn’t Right Anymore

And there you have it – a journey through Toni Morrison’s *Beloved*, a book that refuses to let us look away. From its haunting real-life origins to its profound exploration of love, loss, identity, and the long shadow of slavery, this novel isn’t just a story; it’s a living, breathing testament to the human spirit’s capacity for both unimaginable suffering and astonishing resilience. It reminds us that memory, though painful, is essential for healing, and that even in the darkest corners of history, heroism can blossom in the quietest acts of courage. So, if you haven’t already, dive into its pages. It’s a read that will challenge you, move you, and ultimately, stay with you long after the final word. What an incredible legacy, right?