The term ‘cult’ conjures vivid and often unsettling images in the popular imagination – secret societies, charismatic leaders, and beliefs far removed from the mainstream. It’s a word frequently loaded with negative connotations, instantly sparking discussions of manipulation, isolation, and extreme devotion. But what precisely constitutes a ‘cult,’ and how has our understanding of these social groups evolved over time?

Far from being a simple label, the concept of a cult has been an ongoing source of contention among scholars across various fields of study, from sociology and religious studies to psychology. Its definitions have shifted, diverged, and sparked significant debate, reflecting a complex interplay between academic rigor, popular perception, and real-world impact. To truly grasp the essence of these phenomena, we must move beyond sensationalism and delve into the nuanced, analytical frameworks developed to explain them.

This article embarks on an insightful journey to unpack the multifaceted world of social groups often labeled as ‘cults.’ We will explore their origins, the sociological theories that attempt to classify them, the historical shifts in their study, and the various societal reactions they provoke. By examining the academic lens through which these groups are understood, we can gain a clearer perspective on a term that, as Susannah Crockford notes, ‘is a shapeshifter, semantically morphing with the intentions of whoever uses it.’

1. **The Evolving Definition of ‘Cult’: From Worship to Pejorative Label**The journey of the word ‘cult’ from its Latin root to its modern usage is a fascinating linguistic and cultural narrative. Originally derived from the Latin term ‘cultus,’ meaning worship, it once indicated ‘a set of religious devotional practices that is conventional within its culture, is related to a particular figure, and is frequently associated with a particular place, or generally the collective participation in rites of religion.’ In this older sense, referring to the ‘imperial cult of ancient Rome,’ for instance, carried no pejorative weight, simply describing established forms of veneration.

However, as centuries passed, the term began to acquire a very different flavor. A derived sense of ‘excessive devotion’ arose in the 19th century, and its usage was not always strictly religious. By the 1930s, new religious movements became an object of sociological study within the context of religious behavior, further shaping the term’s academic application. Yet, it was primarily in popular culture that the word started to embody a more sinister meaning.

In modern English, the term ‘cult’ is generally a pejorative, carrying derogatory connotations. It is ‘variously applied to abusive or coercive groups of many categories, including gangs, organized crime, and terrorist organizations.’ This negative connotation has largely overshadowed its older, more neutral meaning, leading to its prevalent association with ‘social groups which have unusual, and often extreme, religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals,’ frequently coupled with ‘extreme devotion to a particular person, object, or goal.’ This semantic morphing highlights how deeply cultural perceptions influence our vocabulary and understanding of social phenomena.

2. **Sociological Foundations: Weber’s Charismatic Authority and Church-Sect Distinction**To truly understand how academics began to categorize and analyze religious groups, we must look to foundational sociological thinkers. Max Weber, a pivotal figure in the academic study of cults, laid crucial groundwork with his theorizations of charismatic authority and his distinct division between churches and sects. Weber’s insights helped establish a framework for distinguishing between different forms of religious organization based on their structure, leadership, and relationship with broader society. His work is still referenced today when examining the dynamics within various religious movements.

Weber’s concept of charismatic authority is particularly relevant here. He described a form of leadership where authority derives from the extraordinary personal qualities of an individual, often perceived as divine or supernatural. This type of leadership is frequently observed in the early stages of new religious movements, where a powerful personality can inspire intense devotion and loyalty among followers. Understanding this dynamic is key to comprehending how many groups, later labeled as cults, initially form and attract adherents.

The distinction between ‘churches’ and ‘sects’ also provided a critical analytical tool. Churches, in Weber’s view, tend to be large, inclusive, and established religious organizations that are integrated into society. Sects, on the other hand, are smaller, more exclusive groups that often break away from established churches, maintaining some continuity with traditional beliefs but often holding a more adversarial stance towards the mainstream. This initial typology offered a lens through which sociologists could begin to differentiate various religious expressions, paving the way for further refinements in understanding newer, less conventional movements.

3. **Troeltsch and Becker’s Typology: Categorizing Religious Experiences and Group Structures**Building upon Weber’s seminal work, German theologian Ernst Troeltsch further elaborated on the church-sect division, introducing a crucial third category: ‘mystical’ religion. This addition was significant because it accommodated more personal or individual religious experiences, acknowledging that not all religious expressions fit neatly into either a large, institutionalized church or a smaller, break-off sect. Troeltsch recognized the diversity of human spiritual seeking, providing a more comprehensive framework for classifying religious phenomena that extended beyond communal worship to encompass solitary or idiosyncratic spiritual paths.

American sociologist Howard P. Becker then took this typology a step further, bisecting Troeltsch’s initial two categories. He refined the ‘church’ category into ‘ecclesia’ and ‘denomination,’ and the ‘sect’ category into ‘sect’ and ‘cult.’ This specific elaboration by Becker is particularly important for our discussion, as it gave the term ‘cult’ a distinct, though still academic and non-pejorative, sociological meaning.

In Becker’s formulation, akin to Troeltsch’s ‘mystical religion,’ a cult refers to ‘small religious groups that lack organization and that emphasize the private nature of personal beliefs.’ This definition highlights the unorganized, often emergent quality of cults in their earliest stages, contrasting them with the more structured nature of sects, denominations, and ecclesia. It underscores an emphasis on individual experience and novel beliefs, which often characterizes groups later subject to public scrutiny and the pejorative label. These academic distinctions, though complex, are vital for navigating the intricate landscape of religious studies.

4. **Deviance and Tension: Cults as Outsiders to Mainstream Religious Culture**Later sociological formulations continued to build on these foundational characteristics, placing an additional emphasis on cults as ‘deviant religious groups,’ precisely those ‘deriving their inspiration from outside of the predominant religious culture.’ This crucial aspect underscores one of the primary reasons why these groups often come into conflict with, or are viewed with suspicion by, mainstream society. Their beliefs and practices are not simply different; they often challenge the accepted norms and traditions of the dominant cultural or religious landscape.

This deviation often leads to ‘a high degree of tension between the group and the more mainstream culture surrounding it,’ a characteristic they sometimes share with religious sects. However, a key distinction remains: ‘sects are products of religious schism and therefore maintain a continuity with traditional beliefs and practices, whereas cults arise spontaneously around novel beliefs and practices.’ This means that while a sect might diverge on interpretation, a cult often introduces entirely new doctrines or entirely new spiritual paths.

The ‘novel beliefs and practices’ that define cults, in this sociological sense, position them distinctly outside the established religious order. This outsider status can contribute to both their appeal for those seeking alternative spiritual paths and the apprehension they generate within the wider community. It’s this inherent tension and perceived deviance that often fuels the popular, negative connotations of the term, transforming a descriptive sociological category into a judgmental societal label. The resistance to rigorous definition, as Susannah Crockford notes, points to ‘a religion or religion-like group ‘self-consciously building a new form of society’, but that the rest of society rejects as unacceptable.’

5. **Bainbridge and Stark’s Three Cult Forms: Audience, Client, and Movement**Sociologists William Sims Bainbridge and Rodney Stark, prominent figures in the study of new religious movements, offered a further, highly influential distinction in understanding cults. They argued for differentiating between three distinct kinds of cults: ‘cult movements, client cults, and audience cults.’ This typology introduced a dynamic element, acknowledging that these groups are not monolithic but exist across a spectrum of organization and engagement, all of which share a ‘compensator’ or rewards for the things invested into the group. This framework provides a practical lens for observing how cults function and interact with their members and the wider world.

‘Audience cults,’ according to Bainbridge and Stark, are the most loosely organized. They are often ‘propagated through media’ and involve individuals who consume cultic ideas without necessarily joining a formal group. Think of someone who follows a particular spiritual guru through books or online content, but doesn’t engage in communal practices. This type represents a broad reach of influence, where ideas can spread widely without demanding deep commitment or organizational structure from followers.

‘Client cults,’ on the other hand, offer specific services to their adherents. These might include ‘psychic readings or meditation sessions,’ where individuals pay for or participate in activities that provide a direct, transactional benefit. The relationship here is more active than an audience cult, but often still lacks the totalizing commitment of a full ‘cult movement.’ Finally, a ‘cult movement’ is defined as ‘an actual complete organization,’ differing from a ‘sect’ in that it is ‘not a splinter of a bigger religion.’ These are the fully formed, distinct new religious groups with their own comprehensive belief systems and social structures. The fascinating aspect of this typology is its fluidity, as ‘One type can turn into another, for example the Church of Scientology changing from audience to client cult,’ demonstrating the evolutionary nature of these movements.

6. **The Psychology of Affiliation: John Lofland’s Study on Conversion**Moving beyond theoretical classifications, academic research also sought to understand the practical dynamics of how individuals actually join these groups. A seminal work in this area comes from sociologist John Lofland, who in the early 1960s, meticulously studied the activities of Unification Church members in California. His research focused on their efforts to promote their beliefs and, crucially, to win new members, offering invaluable insights into the process of religious conversion and affiliation.

Lofland’s groundbreaking findings, published in his 1964 doctoral thesis and later as the book *Doomsday Cult: A Study of Conversion, Proselytization, and Maintenance of Faith*, revealed something profoundly significant. He noted that ‘most of their efforts were ineffective and that most of the people who joined did so because of personal relationships with other members (often family relationships).’ This observation challenged simplistic notions of ‘brainwashing’ or mass persuasion, highlighting instead the powerful role of interpersonal connections in drawing individuals into new religious groups.

This work is widely considered ‘one of the most important and widely cited studies of the process of religious conversion.’ It emphasizes that human relationships, trust, and pre-existing social bonds are often far more influential than abstract doctrines or charismatic appeals alone. Rather than a sudden, dramatic transformation, Lofland’s study depicted conversion as a more gradual process, deeply embedded in the social fabric and personal networks of potential adherents. This shifts the focus from an external force acting upon an individual to an internal decision often facilitated and reinforced by close social ties, offering a more nuanced understanding of how people come to embrace novel belief systems.

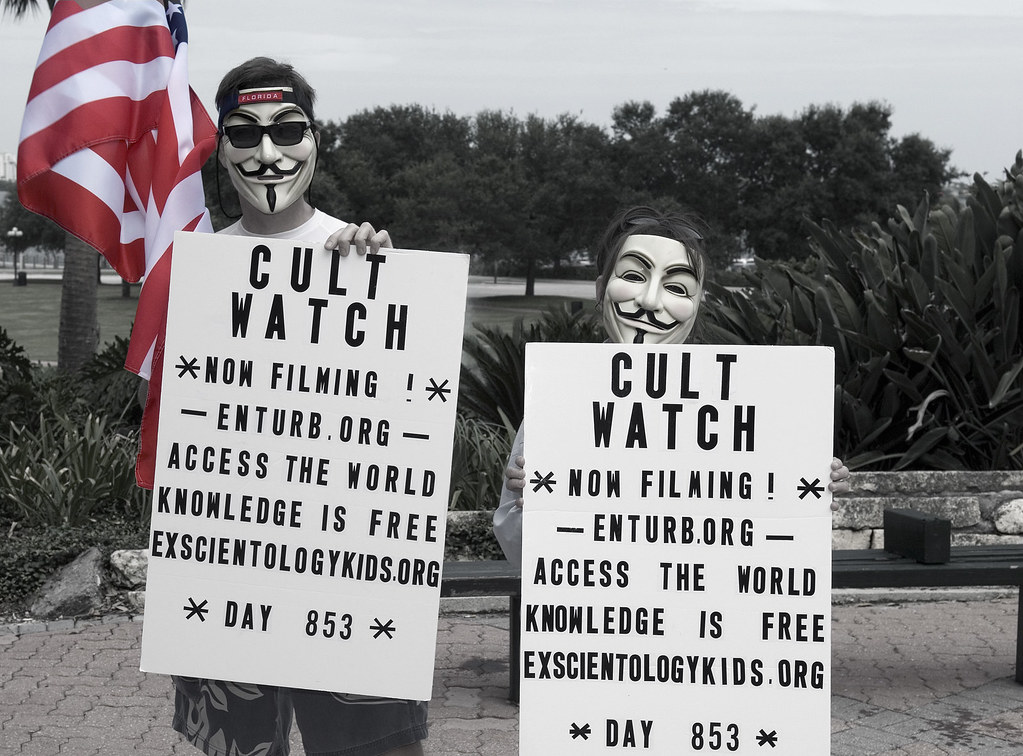

7. **Destructive Cults: The Anti-Cult Movement’s Pejorative Lens**The term “destructive cult” frequently dominates public discourse, largely fueled by the anti-cult movement itself. These groups define such entities as “unethical, deceptive, and one that uses ‘strong influence’ or mind control techniques to affect critical thinking skills,” implying exploitation and harm. This framing suggests a particular danger, often overshadowing any notion of “benign cults.”

Psychologist Michael Langone, a leading figure in the anti-cult group International Cultic Studies Association, precisely defines a destructive cult as “a highly manipulative group which exploits and sometimes physically and/or psychologically damages members and recruits.” Eli Shapiro, cited in *Cults and the Family*, further characterizes “destructive cultism” as a “sociopathic syndrome,” highlighting “behavioral and personality changes, loss of personal identity, cessation of scholastic activities, estrangement from family, disinterest in society and pronounced mental control and enslavement by cult leaders.” These descriptions paint a grim picture of coercive control and devastating personal loss.

Yet, academic reception of “destructive cult” is not universal. Researchers often critique its overgeneralization, noting it implies all groups will lead to tragedies like the Peoples Temple mass suicide. John A. Saliba highlights this, showing how the Peoples Temple creates an unfair associative threat for other new religious movements. This contentious labeling even led to the German government being deemed by the Federal Constitutional Court to have defamed the Osho movement with such a label.

8. **Doomsday and Political Cults: Apocalyptic Visions and Ideological Zeal**Beyond “destructive cults,” more specific classifications highlight groups’ core beliefs. “Doomsday cults” are defined by fervent “apocalypticism and millenarianism,” beliefs centered on the imminent end of the world or profound societal transformation. These groups might not just predict disaster but, in extreme instances, attempt to instigate it. A seminal observation comes from the 1950s, when Leon Festinger and colleagues studied the Seekers, a UFO religion, documenting their reactions to a leader’s failed prophecy of global destruction.

Festinger’s work, *When Prophecy Fails*, revealed insights into cognitive dissonance, showing how members often reinforced beliefs despite failed predictions. This unwavering conviction, despite contrary evidence, became a major news topic in the late 1980s, with media often sensationalizing doomsday cults as serious societal threats. A 1997 psychological study further suggested individuals often turn to cataclysmic worldviews after failing to find meaning in mainstream movements, revealing a deeply human, if extreme, search for purpose.

Shifting from cosmic cataclysms, “political cults” focus on “political action and ideology,” aiming to reshape society with often extreme agendas. Whether “far-left or far-right,” these groups attract journalistic and scholarly attention. Dennis Tourish and Tim Wohlforth’s 2000 book, *On the Edge: Political Cults Right and Left*, analyzes a dozen such organizations in the US and Great Britain, critically exploring their cult-like characteristics within a political framework.

9. **The Christian Countercult Movement: Defending Orthodoxy**Understanding opposition is key to cult studies, with the “Christian countercult movement” being an early, enduring force. Established in the 1940s US, this movement actively opposed “non-Christian religions and heretical or counterfeit Christian sects,” setting clear doctrinal boundaries. For evangelical Protestants, who form its core, any religious group claiming Christianity but deemed “outside of Christian orthodoxy” was categorized as a ‘cult’.

Their criteria extended beyond structure to theological tenets: groups “deviate[ing] from the belief that the bible is inerrant” were labeled cults. This focus wasn’t only on internal Christian disagreements but also scrutinized “non-Christian religions like Hinduism,” viewing them as deviations from biblical truth, highlighting a mission to safeguard authentic Christian faith.

A central tenet for Christian countercult activists is not just critique, but active engagement. They “emphasize the need for Christians to evangelize to followers of cults,” turning their academic and theological convictions into a call for spiritual action. This movement seeks to both warn against and guide individuals out of perceived doctrinal impurity toward orthodox Christian belief.

10. **The Secular Anti-Cult Movement: Responding to Perceived Harm and Brainwashing**The late 1960s and 1970s saw the rise of the “secular anti-cult movement” (ACM), a response to flourishing new religions and tragedies like Jonestown. Unlike Christian counterparts, ACM focused on psychological manipulation. Organizations often acted for “relatives of ‘cult’ converts who did not believe their loved ones could have altered their lives so drastically by their own free will,” seeking non-religious explanations.

This search for answers quickly centered on “brainwashing,” a controversial theory advanced by some psychologists and sociologists within the ACM, suggesting “brainwashing techniques were used to maintain the loyalty of cult members.” This became a “unifying theme,” leading to extreme practices like forced “deprogramming.” In media, “cult” gained “increasingly negative connotation,” synonymous with “kidnapping, brainwashing, psychological abuse, ual abuse, and other criminal activity, and and mass suicide.”

However, academic reception of brainwashing was split. Sociologists were “for the most part sceptical,” and by the late 1980s, both psychologists and sociologists largely abandoned brainwashing theories. They recognized that while “less dramatic coercive psychological mechanisms could influence group members,” conversion was “principally an act of a rational choice.” This highlights a persistent disconnect between scholarly understanding and public perception, as mass culture often extends negative connotations to “any religious group viewed as culturally deviant, however peaceful or law abiding it may be.”

11. **Global Governmental Responses: Classifying, Regulating, and Critiquing**The term “cult” has permeated governmental policy worldwide, with the “application of the labels cult or sect to religious movements in government documents” reflecting its popular, negative usage. Sociologists critique this politicized application, arguing it “may adversely impact the religious freedoms of group members,” potentially marginalizing groups based on subjective classifications.

During the counter-cult height in the 1990s, some governments “published lists of cults,” like Belgium, France, and Germany, leading to legal challenges. Belgium’s House of Representatives, for instance, was “condemned” in 2005 for damaging an organization’s image. Yet, governmental approaches vary. Since the 2000s, some have “distanced themselves,” with Austria no longer distinguishing “sects,” and France’s Prime Minister noting original list concerns “had become less pertinent.”

Despite moves towards neutrality in some regions, other governments align “more with the critics,” distinguishing “legitimate” religion from “dangerous,” “unwanted” cults. China exemplifies this with *xiéjiào* (邪教) — “evil cults” or “heterodox teachings” — a label targeting groups “not authorized by the state” or those believed to “challenge the legitimacy of the state,” leading to suppression of groups like Falun Gong.

Similarly, in Russia, the Interior Ministry prepared a list of “extremist groups” in 2008, including “Pagan cults,” and later the Ministry of Justice listed “80 large sects” considered dangerous, encompassing groups like The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and Jehovah’s Witnesses. This global survey highlights vastly different governmental responses to perceived religious threats, shaped by unique historical, political, and cultural contexts.

12. **’Brainwashing’ in the Courts: The Scientific Status of a Controversial Theory**”Brainwashing” wasn’t merely activist rhetoric; it became a contentious legal issue in 1970s American courts. Its scientific status was debated, as it was used to “justify the use of the forceful deprogramming of cult members.” Countering this, critical sociologists supported religious freedom advocates, defending new religious movements’ legitimacy and First Amendment protections.

A landmark moment was *United States v. Fishman* (1990), which “ended the usage of brainwashing theories by expert witnesses such as Margaret Singer and Richard Ofshe.” The court applied the *Frye standard*, requiring scientific theories to be “generally accepted in their respective fields” for admissibility. Brainwashing, it concluded, failed this test.

This ruling was backed by publications from the “APA Task Force on Deceptive and Indirect Methods of Persuasion and Control,” prior court case literature, and expert testimonies from scholars like Dick Anthony. This evidence effectively sidelined the controversial theory from American jurisprudence.

However, across the Atlantic, the reception varied considerably. The governments of France and Belgium, for instance, have taken “policy positions which accept ‘brainwashing’ theories uncritically,” reflecting a more interventionist approach to regulating religious groups. In contrast, nations like Sweden and Italy have remained “cautious with regard to brainwashing” and have adopted “more neutrally” responsive stances to new religions, demonstrating a greater deference to academic critiques. Scholars suggest that the “outrage which followed the mass murder/suicides perpetuated by the Solar Temple” significantly contributed to these anti-cult positions in certain European countries, even sparking concerns among clergy that such laws might adversely affect “some orders and other groups within the Roman Catholic Church.”

**An Unfolding Tapestry of Belief and Scrutiny**

From the ancient Latin *cultus* to the fraught terminology of modern sociology and jurisprudence, our journey through the concept of ‘cults’ reveals not a simple, monolithic phenomenon, but a complex, ever-evolving landscape of human belief, social organization, and societal reaction. We’ve explored how academic distinctions strive for clarity, differentiating by structure, leadership, and tension with the mainstream, while popular and political narratives often weaponize the term, transforming it into a pejorative label fraught with implications of manipulation and harm. The interplay between individual spiritual seeking, communal bonding, and external scrutiny continues to shape how these groups are formed, understood, and ultimately, judged. As new movements emerge and existing ones transform, the conversation around what truly constitutes a ‘cult’ remains as vital and multifaceted as ever, reminding us that behind every label lies a rich, often contentious, human story.