The world of “The Matrix” captivated audiences with its mind-bending premise: what if our perceived reality is nothing more than an elaborate computer simulation? For many, it was pure science fiction, a thrilling escape into a dystopian future. Yet, beneath the layers of special effects and iconic action sequences lies a philosophical quandary that has intrigued thinkers for centuries and, surprisingly, gained significant traction in contemporary scientific and philosophical discourse. The idea that we might be living inside a meticulously crafted digital universe isn’t just a cinematic fantasy; it’s a profound theory known as the simulation hypothesis, and it asks us to fundamentally reconsider everything we think we know.

This isn’t a new-age spiritual belief or a flimsy conspiracy theory. Instead, it’s a meticulously constructed argument, bolstered by advancements in computing and a deep understanding of consciousness. From ancient Eastern parables to Western philosophical stalwarts, the notion that reality might be an illusion has persistently surfaced throughout human history. What was once the domain of mystics and philosophers has now found a renewed voice through the lens of cutting-edge technology and theoretical physics, pushing us to ask: could “The Matrix” actually be a blueprint for our own existence?

Join us as we dive deep into the fascinating world of the simulation hypothesis. We’ll peel back the layers of this captivating theory, exploring its rich historical tapestry, dissecting the seminal arguments that give it weight, and examining the compelling reasons why many serious minds believe there’s a better than even chance that our reality isn’t quite as real as it seems. Prepare to have your perceptions challenged, your curiosity ignited, and perhaps, your understanding of existence permanently altered.

1. **The Core Idea: Reality as a Computer Simulation** The bedrock of “The Matrix” theory, and indeed, the central tenet of much philosophical debate today, is the simulation hypothesis itself. At its heart, this hypothesis proposes a startling possibility: what we experience as the real world—the tangible objects, the vast cosmos, our very consciousness—is not fundamental reality but rather an elaborate, sophisticated computer simulation. In this framework, humans are not biological entities existing in a base reality, but rather “constructs” within this simulated environment, indistinguishable from genuine biological life from their own internal perspective.

This isn’t to say that our sensations are false or that our experiences are meaningless. Rather, it suggests that the underlying substrate of our existence is not physical in the way we traditionally understand it, but computational. Imagine an advanced civilization, far beyond our current technological capabilities, running a program so complex and detailed that it generates an entire universe, complete with conscious beings. Our lives, our history, our universe, could all be lines of code, meticulously rendered and updated by an unseen intelligence.

The profound implication is that the fundamental nature of reality might be informational. This concept shifts our understanding from a purely materialist worldview to one where information processing is paramount. It opens up questions about the nature of consciousness itself: if a simulated entity can possess consciousness, what does that say about the origins and requirements for our own awareness? It’s a hypothesis that forces us to grapple with deep epistemological questions, challenging our most basic assumptions about what is real and how we know it.

2. **Ancient Roots: Zhuangzi’s Butterfly Dream & Indian Maya** While the term “simulation hypothesis” is a product of our digital age, the underlying philosophical questioning of reality’s authenticity stretches back millennia. Human history is rich with thinkers who pondered the deceptive nature of appearances, using metaphors like dreams, illusions, and hallucinations to illustrate the gap between how things seem and how they might actually be. These ancient insights laid crucial groundwork for later, more formalized skeptical arguments.

One of the most poetic and oft-cited examples comes from ancient China, with the “Butterfly Dream” of the philosopher Zhuangzi from the 4th century BC. As the story goes, Zhuangzi dreamt he was a butterfly, flitting and fluttering, utterly content and unaware of his human form. Upon waking, he was solid and unmistakable Zhuangzi, but a profound doubt lingered: “But he didn’t know if he was Zhuangzi who had dreamt he was a butterfly or a butterfly dreaming he was Zhuangzi. Between Zhuangzi and a butterfly there must be some distinction! This is called the Transformation of Things.” This anecdote perfectly encapsulates the elusive boundary between waking and dreaming, and the difficulty of discerning one from the other.

Similarly, in Indian philosophy, the concept of “Maya” speaks to the illusory nature of the perceived world. Maya is often understood as the cosmic illusion that prevents us from seeing the true reality, a veil that conceals the ultimate truth. It suggests that our sensory experiences and the world as we perceive it are not the ultimate reality but a product of cosmic deception or misunderstanding. These ancient perspectives, though culturally distinct, share a common thread: a deep-seated suspicion that the world we inhabit might not be as straightforward or as ultimately “real” as it appears.

3. **Western Philosophical Precursors: Plato’s Cave & Descartes’ Evil Demon** The Western philosophical tradition also boasts a formidable lineage of thinkers who grappled with the distinction between appearance and reality, providing powerful metaphors and arguments that echo through the modern simulation hypothesis. Their contributions laid much of the conceptual bedrock for later skeptical inquiries.

Perhaps the most famous of these is Plato’s allegory of the cave, found in his work “Republic.” Plato analogized human beings to chained prisoners in a cave, able to see only shadows cast by objects passing in front of a fire behind them. These prisoners mistake the shadows for reality, never perceiving the true forms that cause them. For Plato, the visible world we inhabit is merely a shadow of a more perfect, true reality – the World of Forms. The allegory is a potent illustration of how deeply ingrained our illusions can be and how difficult it is to break free from a perceived reality to grasp a higher truth.

Centuries later, René Descartes philosophically formalized these epistemic doubts with his “evil demon” hypothesis. In his “Meditations on First Philosophy,” Descartes posited the idea of an “evil demon, supremely powerful and cunning,” who has employed all its energies in deceiving him. This demon could be manipulating all his sensory inputs, making him believe in an external world that doesn’t exist, or making him feel sensations that are not truly there. Descartes used this extreme skeptical scenario to question the certainty of all empirical knowledge, seeking an indubitable foundation for belief. This concept, often presented in modern variations like the “brain in a vat” scenario, directly prefigures the simulation hypothesis by asking if an external agency could systematically deceive our senses about the nature of our reality.

4. **Early Computational Thinking: Zuse’s Digital Physics** As philosophy pondered the nature of reality, the rise of computing in the 20th century provided a new, technological lens through which to view these age-old questions. The idea that the universe itself might be fundamentally computational began to take root, moving the discussion from purely abstract philosophical thought experiments to more concrete theoretical models.

A pivotal figure in this shift was Konrad Zuse, the German computer pioneer. In 1969, Zuse published his influential book, “Calculating Space” (“Rechnender Raum”), which delved into automata theory. In this work, Zuse proposed the groundbreaking idea that the universe was fundamentally computational, a concept which became known as digital physics. This theory suggests that reality at its most basic level isn’t continuous but discrete, like the pixels on a screen or the bits in a computer program. The laws of physics, in this view, could be seen as algorithms, and particles as data processing units.

Zuse’s proposition was radical for its time, suggesting that the intricate workings of the cosmos could be explained through the language of computation. It challenged the prevailing continuous models of physics and offered a new paradigm where information processing is inherent to the fabric of existence. While not directly stating we *are* in a simulation, digital physics provides a conceptual framework wherein a simulated universe becomes theoretically plausible, because if reality is inherently computational, then the distinction between a ‘natural’ computation and a ‘simulated’ one becomes less distinct.

5. **AI and Future Intelligences: Hans Moravec’s Speculations** Building upon the nascent ideas of digital physics and advancing artificial intelligence, roboticist Hans Moravec further explored related themes through the lens of artificial intelligence in the late 20th century. Moravec’s work brought the discussion closer to the realm of simulated consciousness and the potential for future civilizations to create realities for their forebears, directly bridging to the core of the simulation hypothesis.

Moravec discussed concepts like mind uploading, envisioning a future where human consciousness could be transferred to digital substrates, effectively allowing beings to exist in computational environments. This wasn’t merely about creating intelligent machines, but about replicating, preserving, and even enhancing conscious experience within a synthetic realm. Such a development would shatter the traditional notion that consciousness is uniquely tied to biological brains, suggesting instead that it could arise from any system that implements the right computational structures and processes.

Crucially, Moravec went on to speculate that our current reality might itself be a computer simulation created by future intelligences. His exploration of “mind uploading” and related themes led him to ponder that “our current reality might itself be a computer simulation created by future intelligences.” If conscious entities can exist within simulations, then the leap to imagining advanced civilizations running vast “ancestor simulations” becomes less of a fantasy and more of a logical extension of technological progress. His ideas painted a vivid picture of a future where distinctions between “real” and “simulated” beings could blur, offering a direct precursor to the more formalized arguments that would follow.

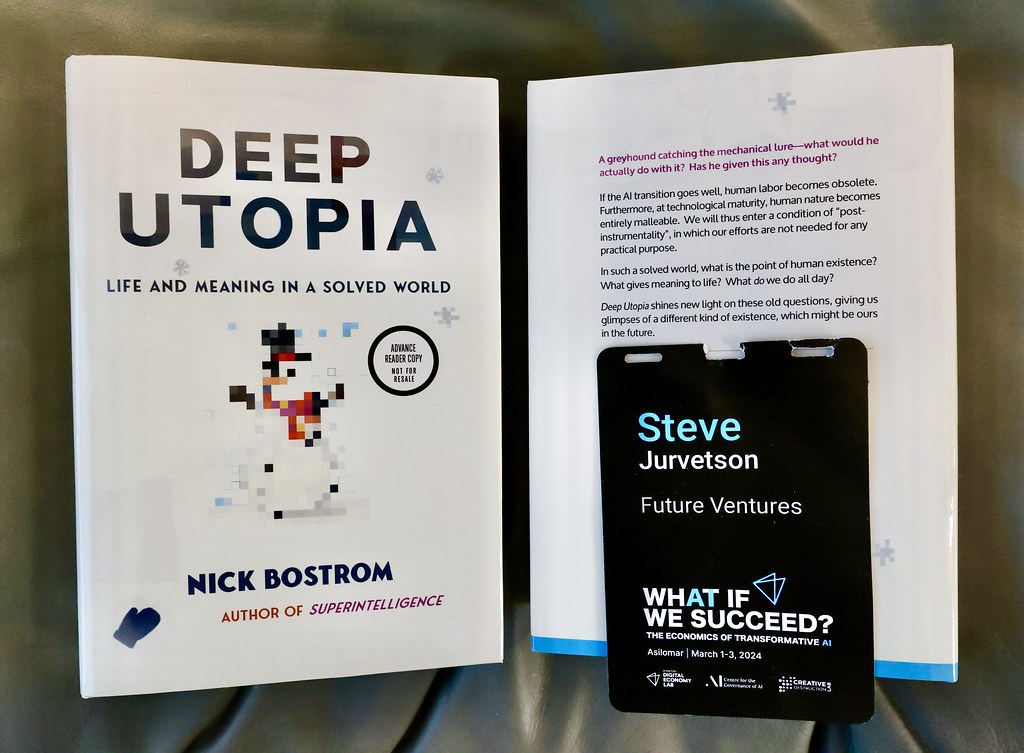

6. **Nick Bostrom’s Foundational Simulation Argument** While the threads of skepticism and computationalism had been weaving through philosophy and science for centuries, it was philosopher Nick Bostrom who, in 2003, brought these disparate ideas together into a concise, powerful, and widely debated framework: the simulation argument. This argument is not a direct assertion that we are in a simulation, but rather a compelling trilemma that suggests one of three unlikely propositions must be true.

Bostrom’s premise is rooted in the anticipation of enormous future computing power. As he states: “Many works of science fiction as well as some forecasts by serious technologists and futurologists predict that enormous amounts of computing power will be available in the future. Let us suppose for a moment that these predictions are correct.” With such power, later generations could run “detailed simulations of their forebears or of people like their forebears,” and given their computational might, “they could run a great many such simulations.” The crucial assumption here is that “these simulated people are conscious (as they would be if the simulations were sufficiently fine-grained and if a certain quite widely accepted position in the philosophy of mind is correct).”

From these premises, Bostrom draws a striking conclusion: “Then it could be the case that the vast majority of minds like ours do not belong to the original race but rather to people simulated by the advanced descendants of an original race.” This implies that if such simulations are widespread and conscious, the statistical likelihood of any given conscious mind, like ours, being in one of those simulations rather than in the “base reality” becomes overwhelming. His argument fundamentally changed the nature of the debate, moving it from mere speculation to a structured logical challenge, compelling serious consideration.

7. **Unpacking Bostrom’s Trilemma: The Three Propositions** The heart of Nick Bostrom’s simulation argument lies in its famous trilemma, a set of three mutually exclusive propositions, one of which must almost certainly be true. This elegant structure forces us to confront the implications of future technological advancement and our place within a potentially simulated cosmos.

The first proposition Bostrom presents is: “The fraction of human-level civilizations that reach a posthuman stage (that is, one capable of running high-fidelity ancestor simulations) is very close to zero.” This suggests a sobering possibility—that humanity, or any comparable civilization across the cosmos, will almost certainly face existential challenges, leading to extinction or a technological stagnation before ever developing the capacity to create advanced, high-fidelity ancestor simulations. It’s a rather pessimistic forecast for our long-term trajectory.

The second proposition states: “The fraction of posthuman civilizations that are interested in running simulations of their evolutionary history, or variations thereof, is very close to zero.” Even if civilizations do achieve posthuman capabilities and survive their early stages, this proposition posits that they will overwhelmingly choose not to create ancestor simulations. Perhaps this decision would stem from overriding legal restrictions, deep moral compunctions, or simply a lack of interest in such resource-intensive historical recreations. It implies a strong, universal convergence away from this particular technological pursuit among advanced civilizations.

Finally, the third proposition, and arguably the most provocative, is: “The fraction of all people with our kind of experiences that are living in a simulation is very close to one.” If civilizations do reach posthuman stages and *do* choose to run ancestor simulations, and if these simulations are high-fidelity enough to be indistinguishable from “base reality” for the simulated beings, then the sheer number of simulated minds would vastly outnumber the original biological minds. In this scenario, statistically, it becomes overwhelmingly probable that any given conscious observer, like us, is living in one of these simulations rather than the “base reality.” Bostrom himself states he sees no strong argument for which of the three is true, noting that “different people pick a different n.” This third proposition is the core logical jump that gives the simulation hypothesis its current philosophical weight and its direct connection to the world of “The Matrix.”

The initial groundwork for the simulation hypothesis, rooted in ancient philosophy and formalized by Nick Bostrom, offers a compelling, if unsettling, vision of our existence. Yet, like any grand theory that dares to redefine reality, it has faced its fair share of rigorous scrutiny and spirited debate. Critics from both philosophical and scientific camps have raised significant objections, challenging the argument’s premises, its practical feasibility, and even its implications for our understanding of consciousness itself. It’s time to dive into these fascinating counter-arguments and explore the profound impact this theory has had, not just in academic halls, but across popular culture.

8. **Criticisms of Bostrom’s Anthropic Reasoning** While Bostrom’s trilemma presents a powerful statistical argument, not all philosophers are convinced by its anthropic reasoning. A core point of contention revolves around the assumption that “Sims” – simulated consciousnesses – would necessarily experience reality in the same conscious way that unsimulated humans do. This leads to a fundamental disagreement over whether the sheer number of simulated minds would indeed make it overwhelmingly probable that we are among them.

Some philosophers propose a different perspective: perhaps it could be “self-evident to a human that they are a human rather than a Sim.” This counter-argument suggests an intrinsic, non-simulatable quality to human consciousness that would allow for a direct, intuitive understanding of one’s fundamental reality, regardless of how perfectly a simulation might mimic it externally. It’s a profound question about the very nature of self-awareness.

Philosopher Barry Dainton offered a clever modification to Bostrom’s trilemma to circumvent some of these consciousness-related disputes. He substituted “neural ancestor simulations” for Bostrom’s “ancestor simulations.” This shift focuses on experiences that range from “literal brains in a vat, to far-future humans with induced high-fidelity hallucinations that they are their own distant ancestors.” The rationale here is that “every philosophical school of thought can agree that sufficiently high-tech neural ancestor simulation experiences would be indistinguishable from non-simulated experiences.”

Dainton’s refined reasoning still leads to a compelling conclusion: either “the fraction of human-level civilizations that reach a posthuman stage and are able and willing to run large numbers of neural ancestor simulations is close to zero,” or some form of “neural ancestor simulation exists.” This adaptation attempts to unify philosophical viewpoints by focusing on the subjective experience of reality, rather than the debate over what constitutes genuine simulated consciousness, thus keeping the core skeptical challenge alive.

9. **Scientific Objections: Feasibility and Physics** Beyond the philosophical nuances, the simulation hypothesis has also encountered significant pushback from the scientific community, particularly from physicists. Renowned physicist Sabine Hossenfelder, for instance, has openly dismissed the hypothesis as “pseudoscience and religion,” arguing that it is “physically impossible to simulate the universe without producing measurable inconsistencies.” For her, the theory lacks the empirical rigor and testability characteristic of true scientific inquiry.

Cosmologist George F. R. Ellis echoed this skepticism, stating that the hypothesis is “totally impracticable from a technical viewpoint” and somewhat dismissively called it “late-night pub discussion is not a viable theory.” These criticisms highlight the immense computational and physical hurdles an advanced civilization would face in creating a universe-scale simulation, questioning whether such an endeavor is even remotely feasible, especially if it requires simulating reality down to its quantum mechanical intricacies.

Sean M. Carroll, another cosmologist, presents an intriguing argument that suggests a contradiction within the hypothesis. He contends that if humans are typical – as the anthropic reasoning assumes – and currently incapable of performing such simulations, this contradicts the arguer’s assumption that it is “easy for us to foresee that other civilizations can most likely perform simulations.” Furthermore, physicist Frank Wilczek raises an empirical objection, observing that the laws of our universe possess “hidden complexity which is ‘not used for anything'” and are “constrained by time and location.” He argues that such superfluous complexity and constraints would be “unnecessary and extraneous in a simulation.”

Wilczek also challenges the hypothesis by pointing out an “embarrassing question”: if our world is simulated, “what is the thing in which it is simulated made out of? What are the laws for that?” This objection highlights a potential infinite regress, suggesting the simulation argument merely shifts the problem of ultimate reality rather than solving it. Additionally, Brian Eggleston has argued that the future humans of our own universe cannot be the ones performing the simulation, as the argument itself posits our universe as the one *being* simulated, suggesting a logical disconnect.

10. **The Consciousness Conundrum: Philosophical Zombies and Vital Substrates** At the heart of many criticisms against the simulation hypothesis lies the profound question of consciousness itself. The theory relies heavily on computationalism, a philosophy of mind suggesting that cognition is a form of computation. If this is true, and if there’s no inherent barrier to generating artificial consciousness, then a simulated reality could indeed contain conscious subjects, thereby fulfilling a key requirement for Bostrom’s “virtual people” simulations.

However, the relationship between computation and the phenomenal qualia of consciousness—the subjective, experiential aspect of being aware—remains hotly debated. While a computer might perfectly replicate the *behavior* of a conscious entity, the question lingers: would that simulated entity actually *feel* anything, or would it merely be a sophisticated “philosophical zombie” behaving appropriately without any inner experience?

This distinction is crucial, as the possibility that consciousness requires a “vital substrate” that a computer cannot provide fundamentally undermines Nick Bostrom’s simulation argument. If genuine consciousness, as humans understand it, cannot be simulated, then humans cannot be simulated consciousnesses in the way his argument implies. This would invalidate the statistical premise that we are more likely to be Sims.

Even if consciousness proves to be non-simulatable, it’s important to remember that the classical “skeptical hypothesis” still holds its ground. Humans could still be “vatted brains,” existing as conscious beings within a simulated environment, even if their consciousness isn’t *generated* by the simulation itself but merely *housed* within its parameters. It’s a subtle but significant difference, highlighting that while virtual reality might engage three senses (sight, sound, optionally smell), a truly simulated reality would encompass all five, including taste and touch, to achieve genuine indistinguishability.

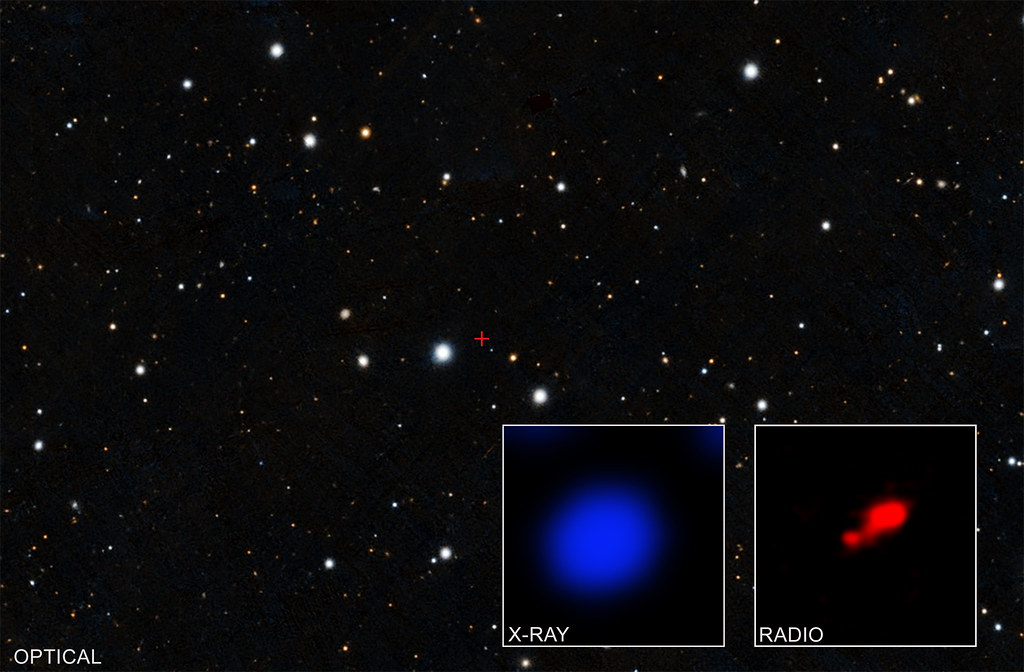

11. **Testing the Simulation: Unveiling Digital Artifacts** Beyond philosophical and theoretical debates, an exciting avenue for tackling the simulation hypothesis involves attempting to physically test it. In 2012, a joint paper by physicists Silas R. Beane, Zohreh Davoudi, and Martin J. Savage proposed a method to test a specific type of simulation. Their approach shifts the discussion from abstract possibility to concrete empirical investigation, aiming to find measurable inconsistencies that would betray our digital existence.

Their core assumption is that if our universe were a simulation running on finite computational resources, the “space-time continuum” would inevitably be divided “into a discrete set of points.” Much like pixels on a screen, this underlying grid-like structure would be a fundamental limitation of any computationally rendered reality. This discretization, they argue, could leave subtle, observable traces within our physical laws and observations.

One of the most intriguing proposed signatures is an “anisotropy in the distribution of ultra-high-energy cosmic rays.” If such a directional dependence were observed, it would be “consistent with the simulation hypothesis” according to these physicists, acting as a potential ‘glitch in the Matrix’ that reveals the grid. Their work draws an analogy to “mini-simulations that lattice-gauge theorists run today to build up nuclei from the underlying theory of strong interactions,” suggesting a blueprint for how a larger universe could be computationally constructed.

More recently, Campbell et al. in 2017 further explored experimental avenues in their paper “On Testing the Simulation Theory,” proposing several additional experiments aimed at unmasking a simulated reality. The overarching epistemological point, as Bostrom himself suggested, is that while a blatant “You are living in a simulation. Click here for more information” window might be purged, “if any evidence came to light, either for or against the skeptical hypothesis, it would radically alter the aforementioned probability.” The hunt for these subtle digital fingerprints continues.

12. **The “Uncertainty Principle”: To Know or Not to Know** The implications of discovering we live in a simulation extend far beyond scientific curiosity, delving into profound ethical and existential questions. Philosopher Preston Greene, in 2019, raised a particularly thought-provoking point: it “may be best not to find out if we are living in a simulation.” His reasoning is stark – if such a truth were revealed, “such knowing might end the simulation.” This aligns with the “1899” Netflix series’ storyline, where amnesia is seemingly induced “to protect the integrity of the simulation.” The idea that our awareness could be a kill switch for our reality is a sobering thought.

Economist Robin Hanson offered an equally intriguing perspective on how a self-aware simulated individual might behave. He argues that a “self-interested occupant of a high-fidelity simulation should strive to be entertaining and praiseworthy in order to avoid being turned off or being shunted into a non-conscious low-fidelity part of the simulation.” It’s a chilling thought: imagine constantly performing for unseen observers, knowing your very existence could depend on your entertainment value.

Hanson further speculates that an individual “who is aware that he might be in a simulation might care less about others and live more for today.” He suggests that “your motivation to save for retirement, or to help the poor in Ethiopia, might be muted by realizing that in your simulation, you will never retire and there is no Ethiopia.” This raises complex questions about moral responsibility, future planning, and the intrinsic value of life within a potentially ephemeral digital construct. Would the knowledge of our simulated nature inspire nihilism, or a renewed appreciation for the subjective reality we experience?

13. **Public Engagement: Celebrity Endorsements and Rebuttals** The simulation hypothesis, with its blend of cutting-edge technology and ancient philosophical riddles, has naturally captured the public imagination, drawing commentary from influential figures across science and technology. Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, in a 2018 NBC News interview, famously estimated the likelihood of the simulation hypothesis being correct at “better than 50-50 odds,” candidly admitting, “I wish I could summon a strong argument against it, but I can find none.” His initial endorsement lent significant weight to the theory in popular discourse.

However, Tyson’s stance later evolved after a discussion with his friend J. Richard Gott, a professor of astrophysical sciences. Gott presented a powerful objection: if simulated universes are capable of producing high-fidelity simulations, and if we are typical, then our current world should also possess this ability. Since our world doesn’t currently demonstrate this, it suggests either we are in the real universe where simulations haven’t been created yet, or we are at the very end of a “very long chain of simulated universes” where the ability to simulate was lost. This “changes my life,” Tyson remarked, highlighting the profound impact of this counter-argument.

Perhaps the most vocal and enthusiastic public proponent of the simulation hypothesis is Elon Musk, the CEO of Tesla and SpaceX. Musk has repeatedly stated that the argument for the simulation hypothesis is “quite strong.” In a podcast with Joe Rogan, he posited, “If you assume any rate of improvement at all, games will eventually be indistinguishable from reality” before concluding “that it’s most likely we’re in a simulation.”

Musk has even gone so far as to speculate that “the likelihood of us living in a simulated reality or computer made by others is about 99.9%,” famously stating in a 2016 interview that he believed there was “a one in billion chance we’re in base reality.” This kind of high-profile endorsement, particularly from a visionary known for pushing technological boundaries, has undeniably propelled the simulation hypothesis into mainstream consciousness, turning a philosophical thought experiment into a widely discussed possibility.

14. **From Page to Screen: The Simulation Hypothesis in Popular Culture** Long before Bostrom’s formal argument, and certainly amplified by it, the captivating notion of a simulated reality has permeated science fiction and popular culture for decades. Daniel F. Galouye’s 1964 novel “Simulacron-3” (also known as “Counterfeit World”) stands as a foundational text, envisioning a virtual city inhabited by conscious beings, almost all of whom are unaware of their simulated nature. This early literary exploration laid crucial groundwork for the themes that would follow.

Galouye’s novel inspired two significant film adaptations: the German made-for-TV film “World on a Wire” (1973), directed by Rainer Werner Fassbinder, and later “The Thirteenth Floor” (1999), which was loosely based on both the book and the German film. These productions, alongside Philip K. Dick’s 1966 short story “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale” (the basis for the “Total Recall” films), firmly established the trope of constructed realities and manipulated memories in cinema, showing humanity grappling with existential deception.

The late 20th and early 21st centuries saw an explosion of this theme. While “The Matrix” (1999) remains the most iconic cinematic representation, its influence is visible across various media. The animated sitcom “Rick and Morty” humorously tackled the concept in “M. Night Shaym-Aliens!” (2014), demonstrating a “low-quality simulation” that failed to fool its protagonists due to its lack of realism. Video games like “Danganronpa 2: Goodbye Despair” (2012) feature a “Neo World Program” as a simulated reality, and “Anonymous;Code” (2022) delves into “infinite or near-infinite number of ‘world layers’ of simulations running inside other simulations,” even presenting a narrative where characters must hack into a higher “real world” layer to solve a simulated apocalypse.

The concept continues to evolve in modern storytelling. “No Man’s Sky” (2016) posits a universe run by a corrupted AI, The Atlas, where “many vastly different iterations of the universe existed.” The “Doctor Who” episode “Extremis” (2017) features a “simulated version” of its characters used as a “practice world for aliens,” with a clever clue—a document listing truly random numbers that, in the simulation, are always the same. Most recently, the Netflix series “1899” (2022) explored an “unfinished story of a simulation scenario” where characters experience “multiplicities and simultaneities,” often with their memories wiped to maintain the simulation’s integrity, echoing Preston Greene’s philosophical warnings.

From ancient doubts to cutting-edge physics, and from philosophical treatises to blockbuster films, the simulation hypothesis has proven itself far more than mere speculation. It is a vibrant, evolving debate that continually challenges our perceptions of reality, consciousness, and what it truly means to be human. Whether we are ultimately living in a meticulously crafted digital universe or a base reality yet to unlock its own simulated potentials, the journey of inquiry itself has reshaped our understanding of the cosmos and our place within it. The ‘red pill’ question of the Matrix remains: how deep does the rabbit hole go, and are we truly prepared for the answer?