“Woman” – it’s a word we hear every day, yet its meaning is as vast and complex as humanity itself. Beyond a simple biological classification, being a woman encompasses a rich tapestry of history, science, culture, and individual identity. From the very cells that make us to the societal roles we inhabit and challenge, womanhood is a journey of constant evolution, resilience, and remarkable diversity.

In a world that often grapples with evolving definitions and understanding, taking a deep dive into what it truly means to be a woman is more crucial than ever. We’re talking about everything from the fascinating etymology of the word itself to the profound biological processes that define female anatomy, and even the often-stark realities of health and lifespan differences. It’s a journey that reveals not just biological facts, but also the deep societal implications that have shaped lives across millennia.

Get ready to explore the foundational elements that contribute to the understanding of womanhood. We’ll break down 14 pivotal aspects, starting with the very core of what makes a woman, biologically and definitionally, then moving through the incredible intricacies of the female body and the factors that influence women’s health and longevity. It’s an insightful look, drawing directly from established knowledge, to truly unpack the essence of what it means to be a woman.

1. **Defining Womanhood: From Biology to Identity**

At its most fundamental, a woman is an adult female human. Before reaching adulthood, a female human is typically referred to as a girl. This basic distinction, however, only scratches the surface of a far more nuanced understanding that has evolved over time and continues to expand today. The biological underpinnings are clear: women are typically of the female sex, inheriting a pair of X chromosomes—one from each parent. This genetic blueprint, coupled with the absence or lack of a functional SRY gene, governs the sex differentiation of the female fetus.

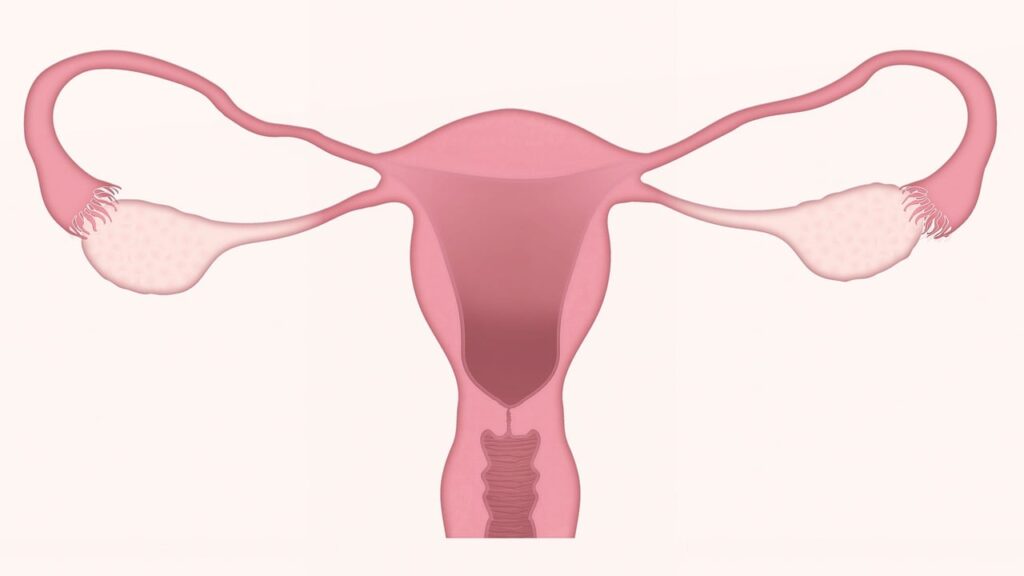

Female anatomy is distinctly organized around the reproductive system, which includes vital internal organs like the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, vagina, and vulva. Beyond these, adult women generally exhibit a wider pelvis, broader hips, and larger breasts compared to adult men. These characteristics are not merely aesthetic; they play crucial roles in facilitating childbirth and breastfeeding, distinguishing female physical form and function from male anatomy.

It’s crucial to acknowledge that the definition of womanhood has broadened to include diverse experiences. Some women are transgender, meaning they were assigned male at birth but identify as female. Others are intersex, possessing unusual sex characteristics such as chromosomes, genitalia, or internal sex organs. This includes women with conditions like Trisomy X or vaginal atresia, further illustrating the spectrum of biological reality within womanhood.

The social sciences’ views on what it means to be a woman have changed significantly since the early 20th century. As women gained more rights and greater representation in the workforce, scholarship in the 1970s moved toward a focus on the sex–gender distinction and the social construction of gender. This deeper understanding highlights that while biology provides a typical framework, identity and individual experience are integral to the contemporary understanding of what it means to be a woman, moving beyond simplistic binaries.

Read more about: Your 2025 Financial Checklist: 12 Smart Career Moves to Secure Your Future in the Evolving Job Market

2. **The Etymological Journey of ‘Woman’**

Have you ever wondered about the origins of the word “woman” itself? It’s a fascinating linguistic journey that spans over a millennium, showcasing how language evolves alongside societal understanding. The spelling we use today has progressed significantly from its Old English roots, starting as “wīfmann,” then evolving through “wīmmann” and “wumman,” before finally settling into the modern “woman.” This evolution isn’t just about spelling; it reflects deeper changes in how ‘human’ and ‘gender’ were perceived.

In Old English, the term “mann” held a gender-neutral meaning, akin to our modern “person” or “someone.” To specifically refer to a female, the word “wīf” or “wīfmann” (literally ‘woman-person’) was used. Meanwhile, a male was called “wer” or “wǣpnedmann,” derived from “wǣpn” meaning ‘weapon’ or ‘penis.’ A significant shift occurred after the Norman Conquest, when “man” gradually began to specifically denote a ‘male human,’ largely replacing “wer” by the late 13th century. This linguistic change fundamentally altered the default understanding of “human” in English.

A popular misconception often links “woman” etymologically to “womb,” but this is not accurate. The word “womb” actually derives from the Old English “wamb,” meaning ‘belly’ or ‘uterus,’ which is cognate with the modern German colloquial term “Wamme” for ‘belly’ or ‘paunch.’ Meanwhile, the consonants /f/ and /m/ in “wīfmann” coalesced to form “woman,” while “wīf” itself narrowed in meaning to specifically refer to a married woman, giving us the word “wife” today. This linguistic detective work reveals the intricate history embedded within everyday words, offering a glimpse into past societal structures and linguistic transformations.

Read more about: Sami’s Journey: Unpacking the Incredible Transformations of Northern Europe’s Resilient Indigenous People

3. **Biological Foundations: Genetics and Hormones**

The intricate biological foundation of womanhood is rooted deeply in our genetics and the symphony of hormones that guide development from conception through life. Typically, the cells of female humans contain two X chromosomes, a distinct genetic signature compared to the male’s X and Y chromosomes. This chromosomal difference is the starting point for sexual differentiation, influencing how an individual develops and functions throughout their life.

During the early stages of fetal development, all embryos initially present phenotypically female genitalia until around week 6 or 7. It’s at this critical juncture that, in male embryos, the gonads differentiate into testes due to the action of the SRY gene on the Y chromosome. Conversely, in female humans, sex differentiation proceeds in a way that is independent of gonadal hormones, following a default developmental pathway. This fundamental process highlights how deeply imprinted gender development is, even before birth.

Hormones, particularly estrogens, play a pivotal role in shaping a female’s body and its characteristics. Produced in both sexes but at significantly higher levels in women, especially during reproductive age, estrogens are the primary female sex hormones. They promote the development of female secondary sexual characteristics, such as breasts and the widening of hips during puberty, contributing to the distinct morphology observed in adult women.

Conversely, the presence of testosterone in a pubescent female can actually inhibit breast development and promote muscle and facial hair. This demonstrates a fascinating interplay of hormones, where their balance and presence dictate various physical expressions. These hormonal balances and interactions are central to the physiological distinctions that characterize female biology, influencing everything from body shape to reproductive capacity.

4. **The Reproductive System: A Biological Marvel**

The female reproductive system is nothing short of a biological marvel, a complex and finely tuned network of organs designed for reproduction and nurturing new life. At its core, the internal female genitalia include the ovaries, which are gonads responsible for producing female gametes, known as ova or egg cells. These cells carry half of the genetic blueprint for a potential offspring, making them crucial for procreation.

Connecting directly to the ovaries are the fallopian tubes, tubular structures that serve as vital conduits, transporting these precious egg cells towards the uterus. The uterus itself is a remarkable organ, with specialized tissue designed to protect and nurture a developing fetus throughout pregnancy. Its cervix acts as a gateway, facilitating the expulsion of the fetus during childbirth. Complementing these are accessory glands, such as Bartholin’s and Skene’s, two pairs of glands that aid in lubrication during sexual intercourse, highlighting the system’s dual function in reproduction and intimate experiences.

Beyond the internal structures, the vulva comprises the external female genitalia, consisting of the clitoris, labia majora, labia minora, and vestibule. The vestibule is particularly significant as it houses both the vaginal and urethral openings, serving as a critical anatomical region. These external components are vital for sexual sensation and protection of the internal organs.

Additionally, the mammary glands, though not strictly part of the internal reproductive system, are crucial for infant nourishment. They are hypothesized to have evolved from apocrine-like glands to produce milk, a nutritious secretion that is the most distinctive characteristic of mammals, along with live birth. In mature women, the breasts are generally more prominent than in most other mammals; this prominence, not strictly necessary for milk production, is thought to be at least partially the result of sexual selection, further underscoring the interplay of biology and evolutionary pressures.

5. **Menstruation, Pregnancy, and Menopause: The Cycles of Life**

From the onset of puberty to the post-reproductive years, women experience a unique series of biological cycles that profoundly shape their lives and health. Female puberty marks the beginning of these cycles, triggering a cascade of bodily changes that enable sexual reproduction via fertilization. In response to chemical signals from the pituitary gland, the ovaries begin to secrete hormones, stimulating physical maturation, including increased height and weight, the growth of body hair, breast development, and importantly, menarche – the onset of menstruation.

Most girls experience menarche between the ages of 12 and 13, marking a significant transition into reproductive capability. This monthly cycle is a complex hormonal dance, preparing the body for a potential pregnancy. The regularity and experience of menstruation can vary greatly among individuals, influenced by genetics, lifestyle, and health.

Pregnancy, the culmination of these reproductive capabilities, typically involves the internal fertilization of a woman’s eggs by sperm, whether through sexual intercourse or artificial insemination. Modern advancements like in vitro fertilization (IVF) even allow fertilization to occur outside the human body, broadening the possibilities for parenthood. Humans are similar to other large mammals in that they usually give birth to a single offspring per pregnancy, but multiple births, most commonly twins, do occur.

What is particularly unusual about human offspring, compared to most other large mammals, is their altricial nature. This means human young are undeveloped at birth and require extensive aid from their parents or guardians to fully mature, highlighting the significant and extended role of human mothers. This dependency period emphasizes the profound commitment required in human reproduction and child-rearing.

As women age, another profound biological transition occurs: menopause. Usually taking place between ages 49 and 52, menopause signifies the permanent cessation of menstrual periods, marking the end of a woman’s ability to bear children. Unlike many other mammals, the human lifespan often extends many years beyond menopause, presenting a unique biological and social phase. This extended post-reproductive life is believed by many biologists to be evolutionarily driven by kin selection, where grandmothers and older women contribute significantly to the care of grandchildren and other family members, demonstrating a powerful role in family and societal structures beyond direct reproduction.

6. **Distinct Health Profiles: Understanding Women’s Wellness**

When we talk about health, it’s vital to recognize that men and women often experience it differently, influenced by a complex interplay of biological, social, and environmental factors. Women’s health is particularly characterized by aspects related to reproduction, but sex differences are evident across the entire spectrum of physiology, from the molecular level to behavioral patterns. These distinctions can be subtle, making it challenging to entirely separate the effects of inherent biology from the influence of the surrounding environment they exist in.

Sex chromosomes and hormones play a significant role, but so do sex-specific lifestyles, metabolism, immune system function, and varying sensitivities to environmental factors. These elements collectively contribute to observed differences in health, perception, and cognition. For instance, women typically have a lower hematocrit – the volume percentage of red blood cells in blood – compared to men. This is attributed to lower testosterone levels, which stimulate the production of erythropoietin.

The normal hematocrit level for a woman is 36% to 48%, contrasting with men’s 41% to 50%. Similarly, hemoglobin, an oxygen-transport protein, also shows differences, with normal levels for women ranging from 12.0 to 15.5 g/dL, compared to men’s 13.5 to 17.5 g/dL. These physiological distinctions mean that diagnostic parameters and typical responses to drugs can also vary between sexes.

Furthermore, women’s cardiovascular health presents unique characteristics. Their hearts possess finer-grained textures in the muscle compared to men’s hearts, and the heart muscle’s overall shape and surface area also differ when controlling for body size and age. Intriguingly, women’s hearts also appear to age more slowly compared to men’s hearts, suggesting unique protective mechanisms at play within the female circulatory system.

Beyond these physiological nuances, some diseases primarily affect or are exclusively found in women, such as lupus, breast cancer, cervical cancer, or ovarian cancer. The medical practice specifically dealing with female reproduction and reproductive organs is called gynaecology, or the “science of women.” This specialized field underscores the unique health needs and research required to address the specific health challenges and wellness requirements throughout a woman’s life.

7. **The Trajectory of Life Expectancy**

A significant aspect of women’s distinct health profile is their generally longer life expectancy compared to men. This advantage isn’t just observed in adulthood; it begins right from birth, with newborn girls demonstrating a higher likelihood of surviving their first year than boys. Worldwide, women tend to live six to eight years longer than men, a statistic that speaks volumes about biological resilience and behavioral patterns across global populations.

However, this global trend is not uniform and can vary significantly based on location and circumstances. For example, in some parts of Asia, discrimination against women has tragically lowered female life expectancy, sometimes to the extent that men in those regions live longer than women. This stark contrast underscores that while biological factors contribute to longer female lifespans, societal and environmental conditions can drastically impact these outcomes, demonstrating that biology is not destiny in isolation from cultural context.

The difference in life expectancy is widely believed to stem from a combination of biological advantages and gendered behavioral differences. Biologically, women may possess inherent protective mechanisms. Behaviorally, women are often less likely to engage in unhealthy behaviors such as smoking and reckless driving, consequently leading to fewer preventable premature deaths from such causes. These healthier lifestyle choices contribute meaningfully to their extended longevity.

While this life expectancy advantage has been pronounced, some developed countries are seeing it evening out. This shift is attributed to both an increase in worse health behaviors among women, notably an increased rate of smoking tobacco, and improved health among men, such as less cardiovascular disease. These trends suggest a convergence in certain health outcomes as societal roles and habits change for both genders.

Despite living longer, the World Health Organization (WHO) wisely notes that it is “important to note that the extra years of life for women are not always lived in good health.” This crucial point prompts a deeper look into the quality of these additional years, emphasizing the importance of not just extending lifespan, but ensuring those years are lived with vitality and without undue suffering. It highlights the ongoing need for comprehensive women’s health initiatives worldwide.

Moving beyond the purely biological, the story of womanhood unfolds into a rich narrative woven from societal expectations, cultural norms, and the relentless pursuit of equality. The next chapter of our journey dives into the profound societal, cultural, and political dimensions that have shaped, challenged, and continue to redefine what it means to be a woman in the modern world. It’s here that we truly see the dynamic interplay between inherent characteristics and the external forces that influence every facet of a woman’s life, from her daily attire to her opportunities in the highest echelons of power. Let’s unpack the social constructions and ongoing struggles that characterize womanhood today.

Read more about: Beyond the ‘Good Old Days’: A Psychology Today Guide to Understanding Why We Get Stuck in the Past and How to Break Free

8. **Evolving Gender Roles and Societal Shifts**

For centuries, traditional gender roles, especially within patriarchal societies, often dictated and limited women’s activities and opportunities. This historical context frequently led to significant gender inequality, where religious doctrines and legal systems alike stipulated specific rules and boundaries for women, often restricting their societal participation to domestic spheres.

However, a seismic shift began in the 20th century, particularly in many societies where restrictions gradually loosened. This era marked a pivotal turning point, as women increasingly gained wider access to careers and the ability to pursue higher education, fundamentally altering long-held societal structures and expectations.

The labor market itself underwent significant changes, moving away from what were once considered “dirty,” long-hour factory jobs to “cleaner,” more respectable office positions that often demanded more education. This transformation directly influenced attitudes toward women in the workplace, fueling a revolution that empowered women to become more career and education-oriented. Such shifts were not merely economic; they represented a profound cultural re-evaluation of women’s capabilities and aspirations.

Despite these undeniable advances, modern women in Western society, and indeed globally, continue to face an array of challenges. Issues in the workplace, education, healthcare, politics, and even motherhood persist. Sexism, in its various forms, remains a significant concern and barrier for women almost anywhere, though its manifestations, public perception, and severity can differ greatly across societies and social classes, reminding us that the fight for true equality is far from over.

Read more about: The Evolving Landscape of Comedy: How Today’s Leading Comedians Shape Social Dialogue and Public Discourse

9. **The Complexities of Religion and Women’s Position**

Religious doctrines have historically played a profound role in shaping women’s societal positions, often stipulating specific gender roles, defining the spiritual authority (or lack thereof) of women, and prescribing social and private interactions between sexes. These teachings also frequently dictate appropriate dressing attire for women, profoundly influencing their daily lives and public presence.

In many countries around the world, these deeply ingrained religious teachings are not confined to spiritual practice alone; they actively influence the criminal and family laws of those jurisdictions. For instance, Sharia law in some regions provides a powerful example of how religious tenets can be codified into legal systems, directly affecting women’s rights and freedoms in matters ranging from marriage and divorce to inheritance and personal conduct.

The intricate and often contentious relationship between religion, law, and gender equality has become a frequent subject of discussion and debate among international organizations. These discussions highlight the ongoing global effort to reconcile traditional religious practices with universal human rights principles, striving to ensure that religious freedom does not come at the cost of gender equity.

Read more about: Understanding Womanhood: A Deep Dive into Biology, Identity, and Societal Evolution

10. **The Persistent Global Challenge of Violence Against Women**

Violence against women remains a pervasive and deeply troubling global issue, explicitly defined by the UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women as “any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.” This broad definition underscores the multifaceted nature of the problem.

This violence is often fueled, particularly outside the West, by deeply entrenched patriarchal social values, a glaring lack of adequate laws, and, in many cases, insufficient enforcement of existing legal protections. Disturbingly, social norms in numerous parts of the world actively hinder progress, with UNICEF surveys revealing alarmingly high percentages of women in some regions who believe a husband is justified in hitting his wife under certain circumstances.

Specific forms of violence against women are tragically diverse and continue to impact millions. These include female genital mutilation (FGM), sex trafficking, forced prostitution, forced marriage, rape, sexual harassment, and the barbaric practices of honor killings, acid throwing, and dowry-related violence. Laws and policies addressing these horrific acts vary significantly by jurisdiction, reflecting a global patchwork of protections and perils.

Historically, other forms of violence like the burning of accused witches, the sacrifice of widows (such as sati), and foot binding were prevalent, demonstrating a long and grim tradition of harm against women. Even today, some regions still contend with accusations of witchcraft leading to severe violence. Moreover, it’s a stark reality that certain forms of violence, like marital rape, have only been recognized as criminal offenses in recent decades and are still not universally prohibited. War and armed conflict exacerbate this, with sexual violence against women, including war rape and sexual slavery, becoming tragically common, as seen in numerous modern conflicts.

Read more about: Beyond the Glare: 9 Women Who Battled Hollywood’s Powerful Smear Machine

11. **Securing Reproductive Rights and Addressing Maternal Health**

Reproductive rights stand as fundamental legal rights and freedoms that directly relate to reproduction and reproductive health. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics articulates these rights clearly, stating that “the human rights of women include their right to have control over and decide freely and responsibly on matters related to their sexuality, including sexual and reproductive health, free of coercion, discrimination and violence.” This emphasizes autonomy and informed choice.

Despite this crucial recognition, access to safe reproductive services remains a global challenge. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that between 2010 and 2014, 56 million induced abortions occurred worldwide each year, with approximately 25 million of these deemed unsafe. These unsafe procedures tragically lead to significantly higher death rates in developing regions compared to developed ones, with sub-Saharan Africa facing the highest mortality.

The WHO attributes these preventable deaths to a range of systemic barriers. These include restrictive laws, poor availability and high cost of services, pervasive stigma, conscientious objection from healthcare providers, and unnecessary requirements like mandatory waiting periods, misleading information, or third-party authorization that delay critical care. Each of these factors contributes to a grim reality for millions of women.

Beyond abortion, maternal mortality, defined by the WHO as “the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy… from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management,” remains a critical issue. In 2017, a staggering 94% of maternal deaths occurred in low and lower-middle-income countries, predominantly in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. The main causes include pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, unsafe abortion, and severe bleeding and infections following childbirth, underscoring the urgent need for improved maternal healthcare globally.

Read more about: Womanhood Unveiled: A Comprehensive Look at Biology, Identity, and Societal Evolution

12. **Cultural Expressions: Clothing, Fashion, and Dress Codes**

The choices women make in their clothing, and indeed the options available to them, are wonderfully diverse and deeply influenced by a tapestry of factors. Across different cultures and regions of the world, these choices are shaped by local customs, religious tenets, deeply held traditions, prevailing social norms, and the ever-shifting currents of fashion trends.

This rich diversity is also reflected in varying societal ideas about modesty. What is considered appropriate or revealing in one culture might be entirely different in another, illustrating the subjective and culturally constructed nature of dress codes. These perceptions are often closely tied to community values and historical precedents.

Intriguingly, in many jurisdictions around the world, laws actively limit what women may or may not wear. A prominent example of this is seen in regard to Islamic dress, where certain jurisdictions legally mandate the wearing of the headscarf. Conversely, other countries, such as France, have laws that forbid or restrict the wearing of specific hijab attire, like the burqa, which covers the face, in public places.

These laws, whether they mandate or prohibit certain articles of dress, are highly controversial and spark considerable debate. They highlight the tension between individual expression, religious freedom, cultural identity, and state control, making women’s clothing choices a complex arena where personal, social, and political forces converge.

13. **Transformations in Fertility and Family Life**

The total fertility rate (TFR), which measures the average number of children a woman will have over her lifetime, varies dramatically across the globe. In 2016, for instance, Niger recorded the highest estimated TFR at 6.62 children per woman, while Singapore registered the lowest at 0.82. Such stark differences profoundly impact demographics and societal structures.

Over the past few decades, many parts of the world have witnessed significant shifts in family structure. In Western countries, for example, there’s been a noticeable trend away from living arrangements that include the extended family, favoring instead the nuclear family model. Alongside this, there’s been a move from marital fertility towards non-marital fertility, meaning more children are born to cohabiting couples or single women.

While births outside marriage are common and fully accepted in some parts of the world, in others, they unfortunately face severe stigmatization. Unmarried mothers can experience ostracism, including violence from family members, and in extreme cases, even honor killings. Adding to this complexity, sex outside marriage remains illegal in many countries, primarily in parts of the Middle East and Africa, creating perilous situations for women.

The social role of the mother also differs widely across cultures. In many societies, women with dependent children are traditionally expected to stay at home and dedicate all their energy to child-rearing, embracing the role of a stay-at-home mother. In contrast, in other places, mothers most often return to paid work, balancing family responsibilities with professional careers, showcasing the varied expectations and pressures placed upon women worldwide.

Read more about: From Sitcom Sweetheart to Silver Screen Sensation: Melissa Rauch’s Incredible Evolution

14. **Advancements and Disparities in Women’s Education and Representation**

Education has long been a battleground for gender equality, with single-sex education historically dominant. While universal education, meaning state-provided primary and secondary education regardless of gender, is now assumed in most developed countries, it is not yet a global norm. However, in many Western nations, women have remarkably surpassed men at numerous educational levels.

Take the United States in 2005/2006, for example: women earned 62% of associate degrees, 58% of bachelor’s degrees, 60% of master’s degrees, and 50% of doctorates. Globally, literacy rates for women have improved significantly, with 87% of the world’s women being literate in 2020, though disparities remain, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. The educational gender gap in OECD countries has also seen considerable reduction over the last 30 years.

Despite these advancements, significant disparities persist, especially in higher education and professional fields. While women now account for more than half of university graduates in several OECD countries, they receive only 30% of tertiary degrees in science and engineering fields. Furthermore, women constitute only 25% to 35% of researchers in most OECD nations, indicating a persistent gap in STEM careers.

The challenges extend into academia, particularly in obtaining faculty positions. Sociologist Harriet Zuckerman observed that the more prestigious an institute, the harder it is for women to secure a faculty role. Historical data shows women were more likely to start as instructors or lecturers, while men more frequently began in tenured positions. In 1989, only 40% of women, compared to 65% of men, held tenured positions in scientific and engineering fields in four-year colleges.

Even in fields where women earn a majority of PhDs, like psychology, they hold significantly fewer tenured positions. These statistics paint a clear picture: while women are achieving impressive educational milestones, the institutional structures and biases within certain professional fields, particularly in academia, still present formidable barriers to equal representation and advancement.

Read more about: Understanding Womanhood: A Deep Dive into Biology, Identity, and Societal Evolution

As we draw this comprehensive exploration of womanhood to a close, it’s clear that the journey from biological blueprint to societal architect is one of unparalleled depth and dynamism. From the genetic code that initiates life to the complex tapestry of cultural norms, political battles, and personal triumphs, womanhood is a testament to resilience, adaptation, and an enduring spirit of progress. It is a story not just of what women are, but of what they overcome, what they achieve, and the boundless potential they continue to unlock in a world constantly learning to see them in their full, magnificent light.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-2177027868-0d3f2dec35ac412599d1b30af431cbbf.jpg)