Ever wondered what truly defines a president’s legacy? While some might focus on hypothetical metrics, the true measure of American leadership often lies in the monumental decisions made, the crises navigated, and the foundational shifts championed throughout history. From the very inception of the republic, the office of the president has been at the epicenter of America’s most transformative periods, shaping not just policy but the very fabric of the nation.

Our journey through U.S. presidential history isn’t about numbers on a scale; it’s about the seismic shifts and quiet revolutions that define a country. We’re diving deep into those critical junctures where the actions of presidents, sometimes in concert with Congress, sometimes in the face of immense national division, carved the path for the United States we know today. Prepare to uncover the fascinating facts behind some of the most impactful presidential decisions and eras.

So, let’s pull back the curtain on the incredible narrative of American leadership, tracing the evolution of a nation through the lens of its highest office. We’ll explore the pivotal moments where foundational principles were forged, territories expanded, and the seeds of future conflicts and triumphs were sown. Get ready to explore the first seven fascinating chapters of this unfolding story.

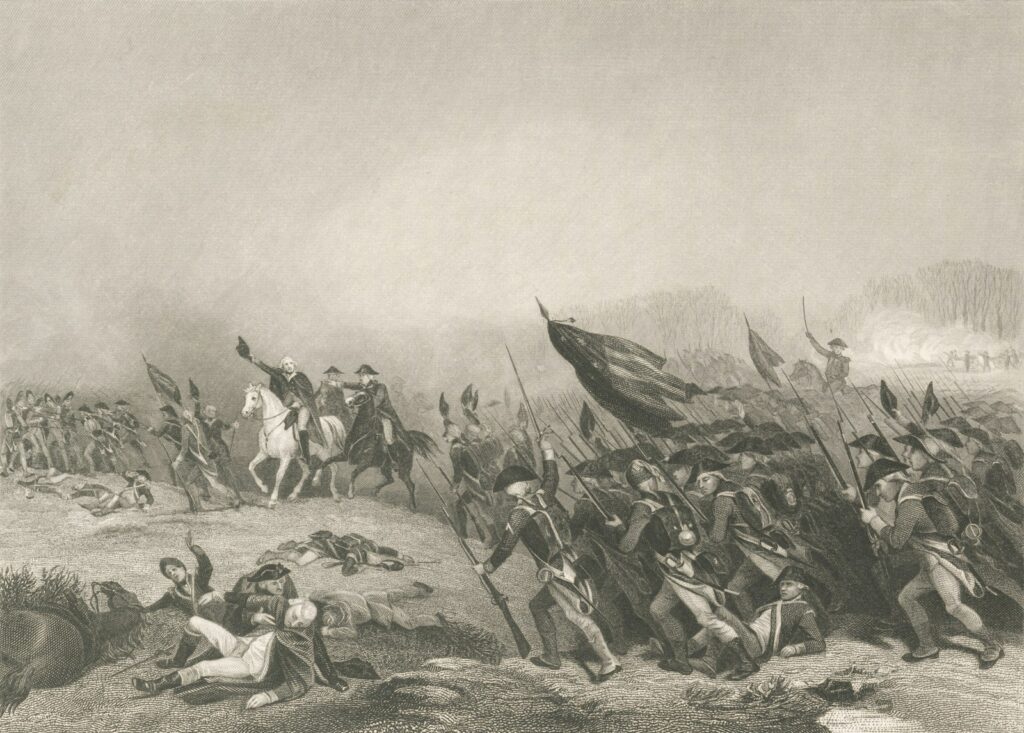

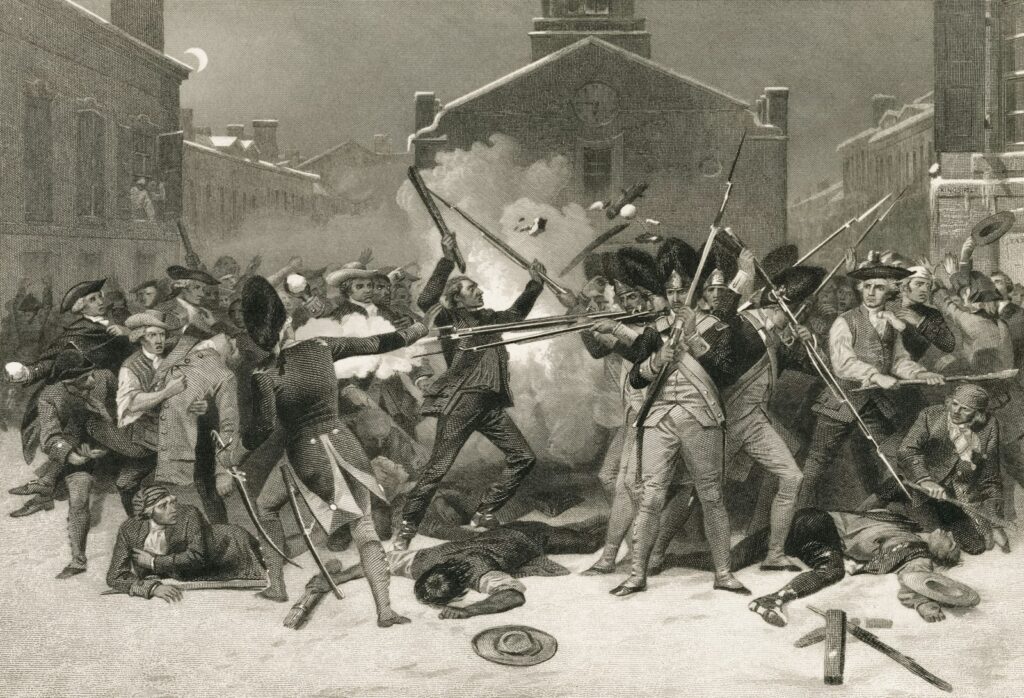

1. **The Spirit of the American Revolution: Founding Principles**: The very idea of the United States was born from a powerful intellectual ferment, deeply inspired by Enlightenment philosophies. The “political values of the American Revolution included liberty, inalienable individual rights, and the sovereignty of the people.” This wasn’t just abstract thought; it was a rejection of traditional power structures, embracing republicanism and explicitly “rejecting monarchy, aristocracy, and all hereditary political power.” The emphasis was firmly placed on civic virtue and a strong vilification of political corruption, setting a high moral bar for the nascent nation.

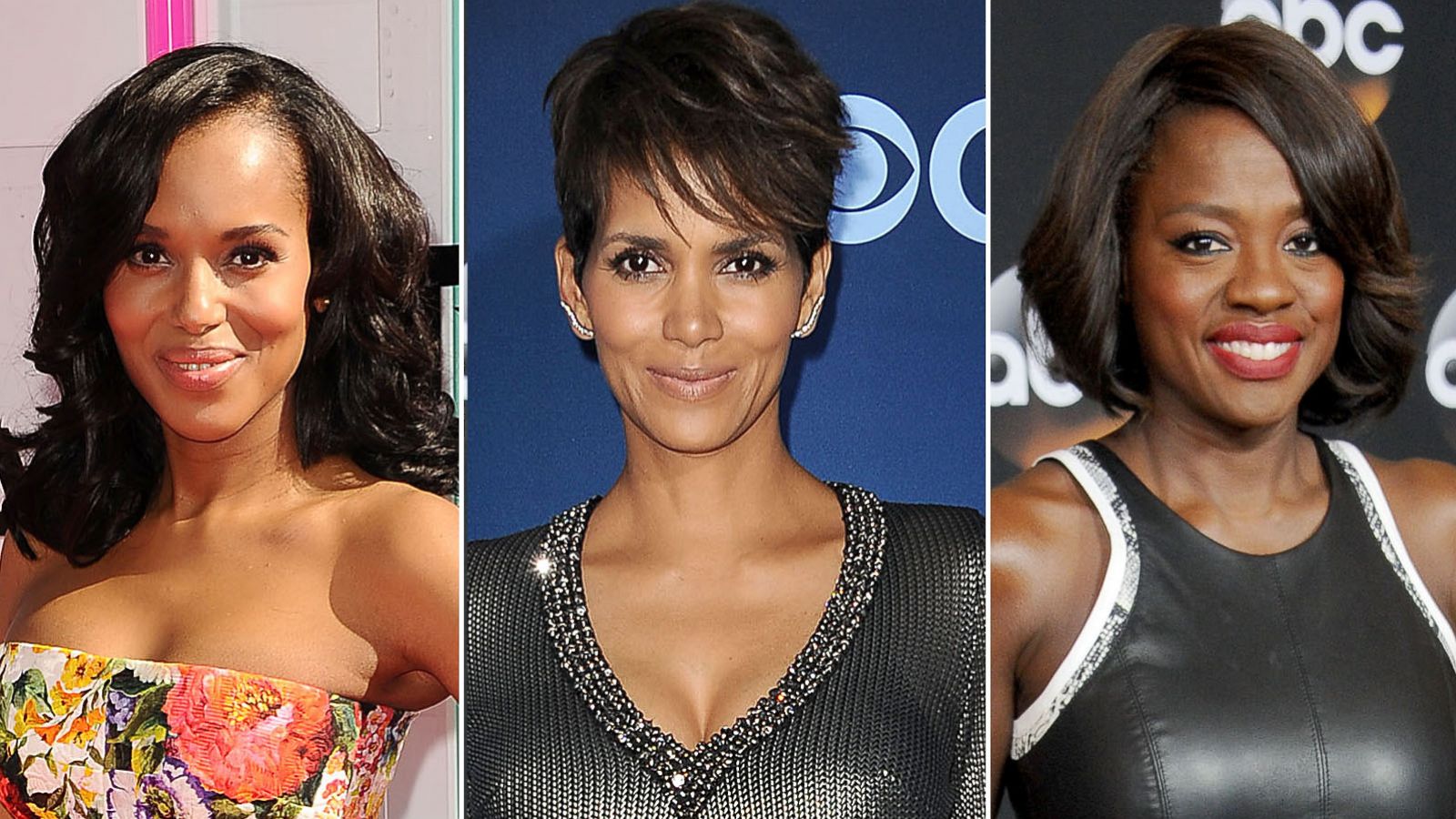

The architects of this new vision, widely known as the Founding Fathers, drew from a rich tapestry of Classical, Renaissance, and Enlightenment ideas. This distinguished group, which included luminaries like George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and James Madison, among many others, channeled these diverse influences into a revolutionary framework. Their collective wisdom and commitment laid the ideological bedrock upon which American governance would be built.

The culmination of this philosophical and political awakening was the Declaration of Independence. Adopted by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, this document was the definitive statement of the colonies’ resolve for self-determination. Thomas Jefferson, entrusted with the momentous task, drafted the Declaration, formally articulating the grievances against the British Crown and the unalienable rights upon which the new nation would stand, marking a pivotal turn toward independence.

2. **Crafting the Republic: The U.S. Constitution and its Branches**: Following the hard-won Revolutionary War and the international recognition of American sovereignty, the young nation grappled with its initial attempt at self-governance under the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union. While ratified in 1781 and in practical effect since its drafting in 1777, this framework established a decentralized government. However, its limitations soon became apparent, creating a need for a more robust and unified system that could effectively govern a growing confederation of states.

The critical moment arrived with the 1787 Constitutional Convention, where delegates convened to overcome the shortcomings of the Articles. The result was the U.S. Constitution, which went into effect in 1789, fundamentally transforming the American political landscape. This landmark document established the United States as a federal republic, a system where power is divided between a national government and individual states, ensuring a balance of authority.

Central to the Constitution’s genius was the creation of a national government with “three separate branches: legislative, executive, and judicial,” all headquartered in Washington, D.C. This innovative structure was designed to provide a comprehensive “system of checks and balances” with the explicit aim “to prevent any of the three branches from becoming supreme.” The Constitution remains the supreme legal document, underpinning the nation’s governance as a “presidential constitutional federal republic and representative democracy.

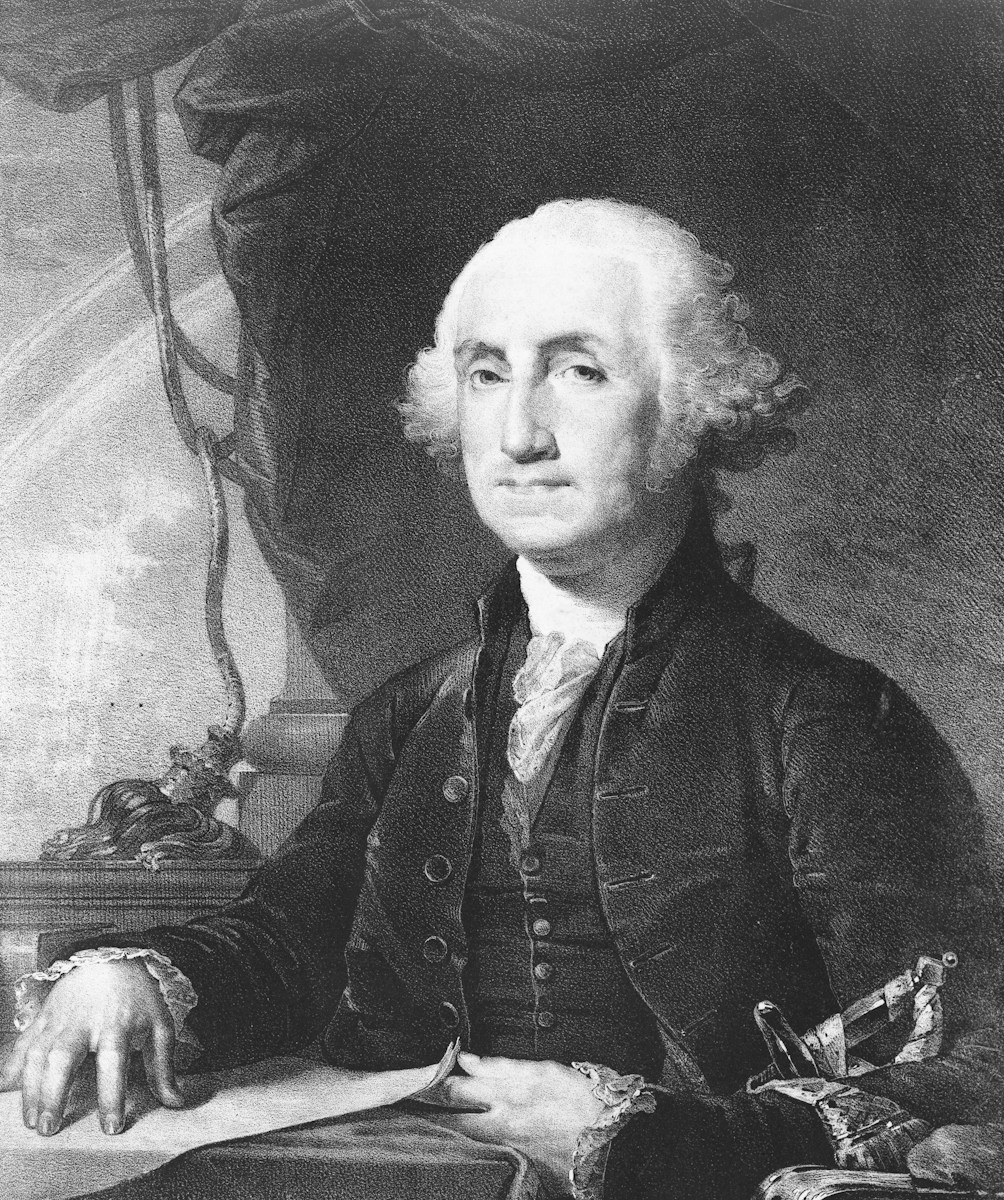

3. **George Washington’s Enduring Legacy: Setting Presidential Precedents**: When the newly drafted Constitution came into effect, the choice for the nation’s first president was clear: George Washington. His election was a moment of immense significance, not just for the office itself but for the very concept of American leadership. Beyond merely holding the title, Washington understood the profound responsibility of establishing norms and traditions that would guide future generations of presidents and shape the executive branch.

Washington’s actions created enduring precedents that solidified the principles of American democracy. His dignified “resignation as commander-in-chief after the Revolutionary War” demonstrated a remarkable commitment to civilian control over the military, preventing the rise of a military strongman. This act alone was a powerful statement about the nature of the republic he helped forge.

Even more impactful was his later “refusal to run for a third term as the country’s first president.” This voluntary relinquishment of power, while not a formal law until much later, established a crucial precedent for “the supremacy of civil authority in the United States and the peaceful transfer of power.” Washington’s conscious choices in office defined the presidency as an office of service, bounded by law and democratic ideals, rather than personal ambition or perpetual rule.

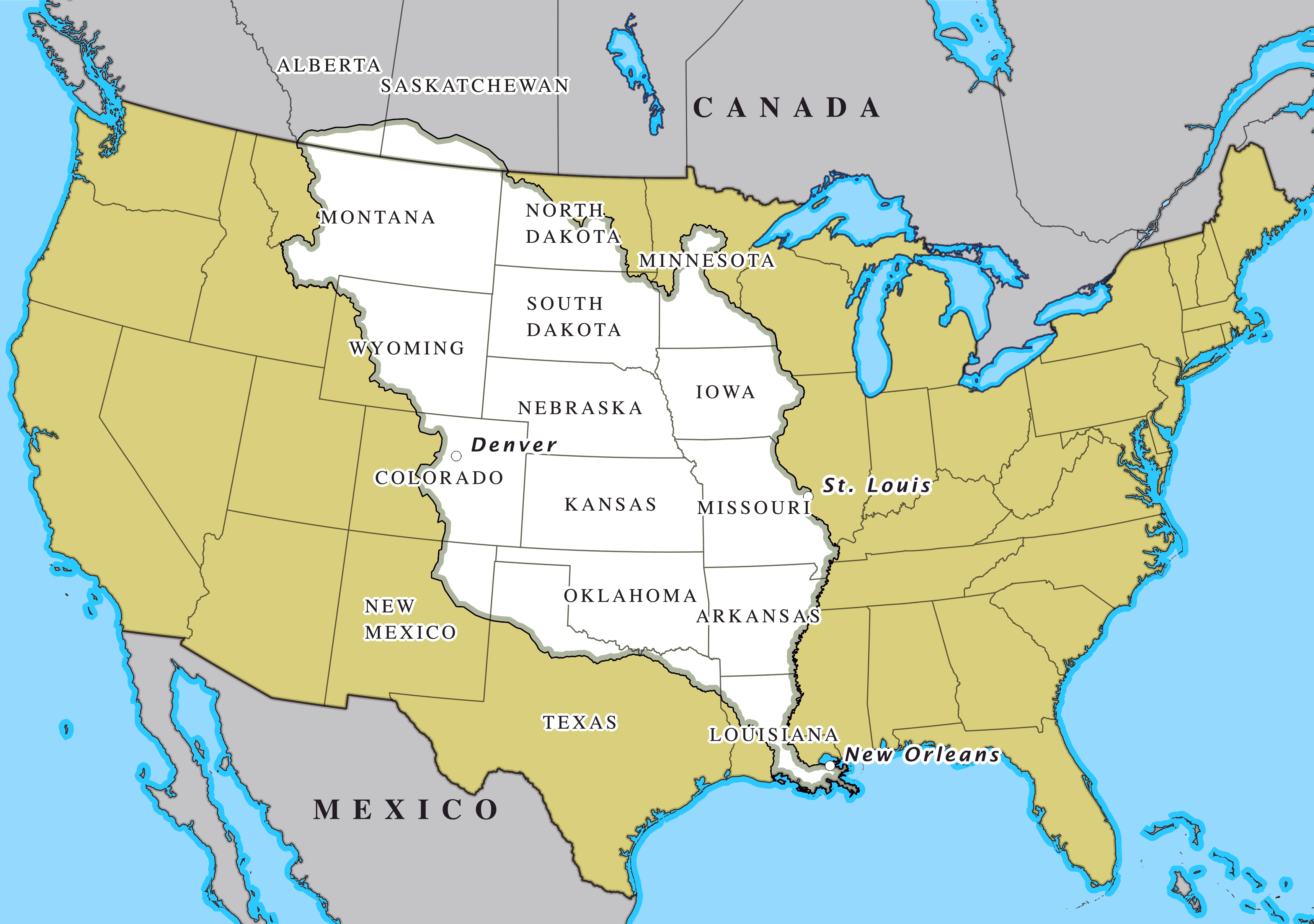

4. **Doubling a Nation: The Louisiana Purchase**: As the 19th century dawned, American settlers were already looking westward, driven by a powerful “sense of manifest destiny”—the belief in the nation’s predetermined expansion across the continent. This burgeoning desire for new lands and opportunities was about to receive an unprecedented boost that would redefine the geographic scope of the United States. It was a strategic move that would profoundly impact the nation’s future.

In 1803, a monumental opportunity arose that seized the imagination of the young republic: the Louisiana Purchase. Through this historic acquisition, the United States bought a vast expanse of territory from France. This single act was nothing short of transformative, as it “nearly doubled the territory of the United States.” It wasn’t just a land deal; it was a gamble on the future, opening up immense new possibilities for agriculture, trade, and settlement.

The sheer scale of the Louisiana Purchase cemented the U.S. as a continental power, laying the groundwork for further westward expansion and the admission of new states. This daring move underscored the executive’s capacity for strategic vision and bold action, even in the early days of the republic, demonstrating how presidential decisions could reshape the very map of the nation.

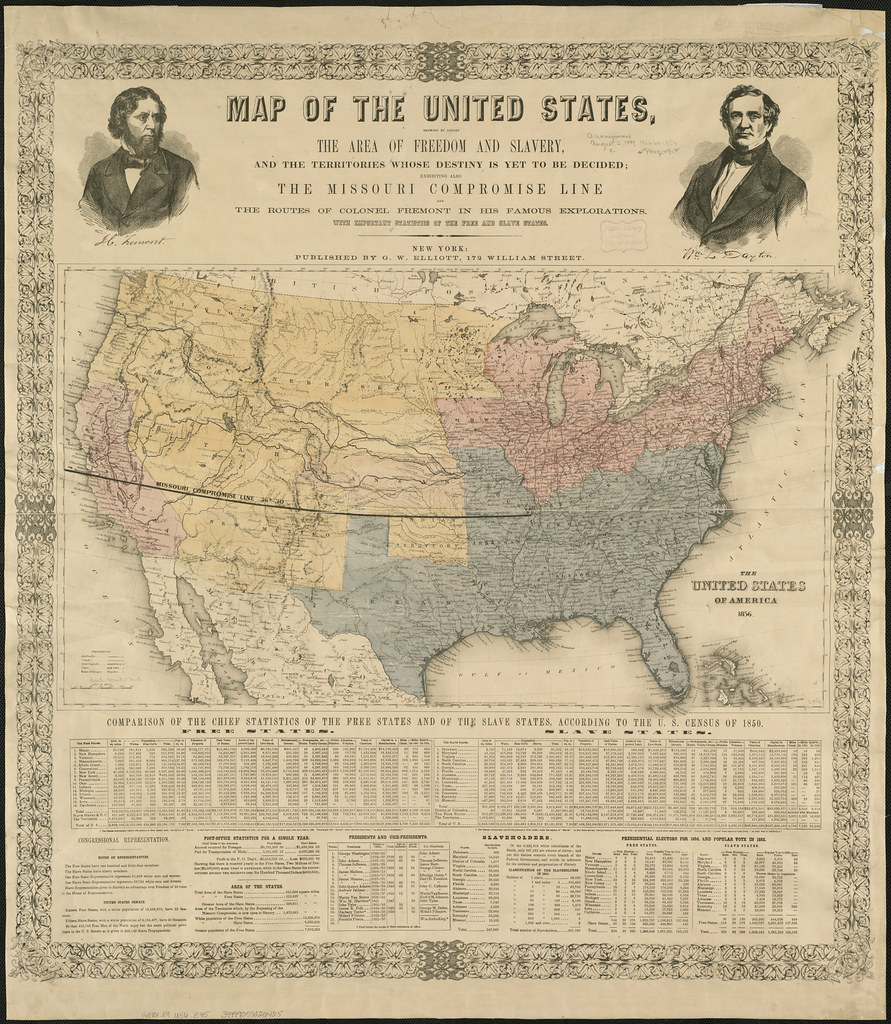

5. **A Nation Divided: The Missouri Compromise and Slavery’s Shadow**: The issue of slavery cast a long and ever-darkening shadow over the young American republic, creating deep sectional divisions that threatened its unity. While legal in the American colonies during the colonial period and integral to the “large-scale, agriculture-dependent economies of the Southern Colonies from Maryland to Georgia,” the practice faced significant questioning during the American Revolution. By the 1830s, an active abolitionist movement in the North led many states to prohibit slavery within their boundaries.

However, in the Southern states, “support for slavery had strengthened,” bolstered by economic factors like the widespread adoption of the cotton gin, which made slavery “immensely profitable for Southern elites.” This created an increasingly volatile political landscape, with states fiercely divided on the expansion of slavery into new territories acquired by the United States. The balance of power in Congress hinged precariously on this contentious issue.

In 1820, an attempt to temporarily resolve this growing crisis came in the form of the Missouri Compromise. This legislative act “admitted Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state,” a clear effort to maintain the delicate balance between slave and free states. Crucially, the compromise “prohibited slavery in all other lands of the Louisiana Purchase north of the 36°30′ parallel,” aiming to prevent further conflict, though it ultimately only postponed the inevitable confrontation over slavery.

6. **The Trail of Tears: A Difficult Chapter of Presidential Policy**: As American settlers continued their relentless push westward, encroaching upon lands inhabited by Native American tribes, the federal government faced the challenge of managing these new frontiers. Unfortunately, rather than fostering coexistence, policies were implemented with a grim focus: “Indian removal or assimilation.” These policies, driven by a desire for land and resources, would lead to one of the most tragic episodes in American history, deeply impacting indigenous populations.

The most significant and devastating piece of legislation in this regard was the Indian Removal Act of 1830. This act, a “key policy of President Andrew Jackson,” authorized the forced relocation of Native American tribes from their ancestral lands in the eastern United States to territories west of the Mississippi River. Despite the humanitarian pleas and legal challenges, the executive branch moved forward with this controversial policy.

The direct consequence of this presidential policy was the infamous Trail of Tears, a series of forced marches that occurred between 1830 and 1850. During this period, “an estimated 60,000 Native Americans living east of the Mississippi River were forcibly removed and displaced to lands far to the west.” The journey was brutal, leading to immense suffering and “causing 13,200 to 16,700 deaths along the forced march,” marking a dark stain on America’s expansionist narrative and a profound betrayal of its founding ideals.

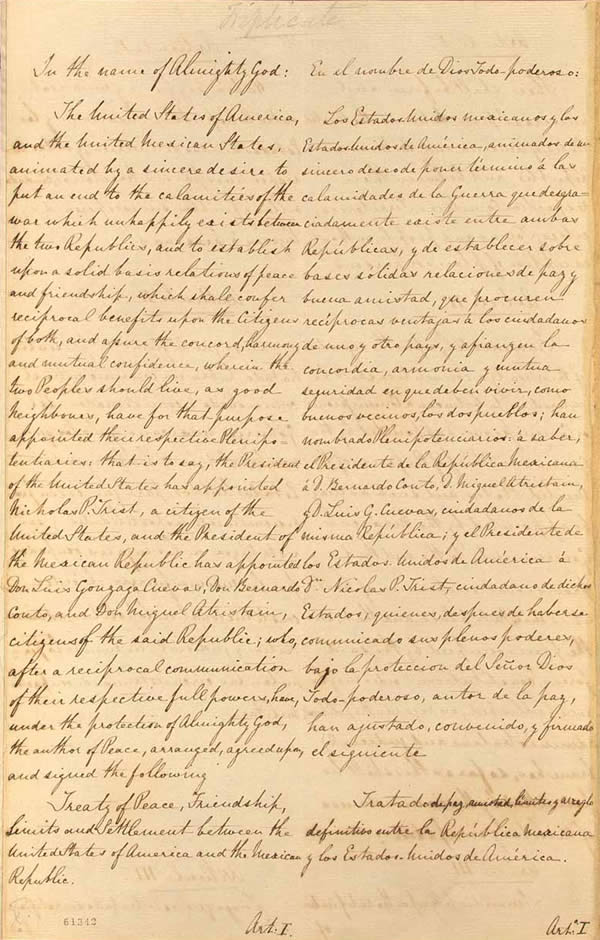

7. **Manifest Destiny’s Reach: The Mexican-American War and Territorial Expansion**: The 1840s were a period of intense territorial ambition for the United States, deeply influenced by the pervasive “sense of manifest destiny.” This era saw the nation consolidate its control over vast new areas, significantly expanding its borders and shaping its continental form. The annexation of independent republics and direct conflict with neighboring nations were hallmarks of this aggressive expansion.

A key step in this process was the annexation of the Republic of Texas in 1845, a move that immediately strained relations with Mexico, which still considered Texas part of its territory. This annexation, combined with the 1846 Oregon Treaty that secured U.S. control of the “present-day American Northwest,” dramatically increased the nation’s landmass and underscored its westward trajectory. However, the Texas dispute was a tinderbox, ready to ignite.

Indeed, the “dispute with Mexico over Texas led to the Mexican–American War (1846–1848).” Following a decisive victory for the U.S. forces, Mexico was compelled to recognize American sovereignty over Texas. Even more significantly, the “1848 Mexican Cession” saw Mexico cede an enormous amount of land, including “New Mexico, and California.” These ceded lands were vast, encompassing not only those future states but also areas that would become “Nevada, Colorado and Utah,” fundamentally reshaping the geography of the United States and the scope of future presidential administration.

Our historical journey continues, moving beyond the early republic’s formation and initial expansions to explore how American leadership grappled with escalating internal divisions, industrial revolutions, global conflicts, and profound social transformations. The subsequent seven defining moments reveal a nation constantly evolving, facing unprecedented challenges, and redefining its role both at home and on the world stage. From the bitter divisions that culminated in civil war to the dawn of the digital age, these presidential eras illuminate the enduring resilience and adaptability of the American experiment.

8. **The Escalation to Civil War: Sectional Conflict and Supreme Court Decisions**: As the nation moved deeper into the 19th century, the issue of slavery, despite the temporary salve of the Missouri Compromise, continued to fester and intensify, creating an ever-widening chasm between the North and South. While Northern states increasingly prohibited slavery within their boundaries, fueled by an active abolitionist movement that had reemerged by the 1830s, support for the institution only strengthened in the Southern states. This was largely due to the widespread adoption of the cotton gin, an invention that made slavery “immensely profitable for Southern elites,” thus cementing its economic and social centrality below the Mason-Dixon line.

The political landscape became a powder keg, with Congress itself becoming a battleground for the fate of slavery’s expansion into new territories. Two legislative acts, in particular, poured fuel on the fire. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, a contentious measure, mandated the forcible return of enslaved people who had sought refuge in non-slave states to their owners in the South. This was followed by the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854, a legislative move that “effectively gutted the anti-slavery requirements of the Missouri Compromise,” by allowing settlers in new territories to decide for themselves whether to permit slavery, leading to violent confrontations and deepening national despair.

Perhaps no single legal decision inflamed the tensions more than the Supreme Court’s infamous Dred Scott ruling in 1857. In a move that shocked many and emboldened Southern slaveholders, the Court ruled against Dred Scott, an enslaved man who had been brought into non-slave territory, asserting he had no legal standing. Even more controversially, the Court simultaneously declared “the entire Missouri Compromise to be unconstitutional.” These legislative and judicial actions, far from resolving the conflict, exacerbated the sectional strife between North and South, ultimately pushing the nation to the precipice of the American Civil War (1861–1865).

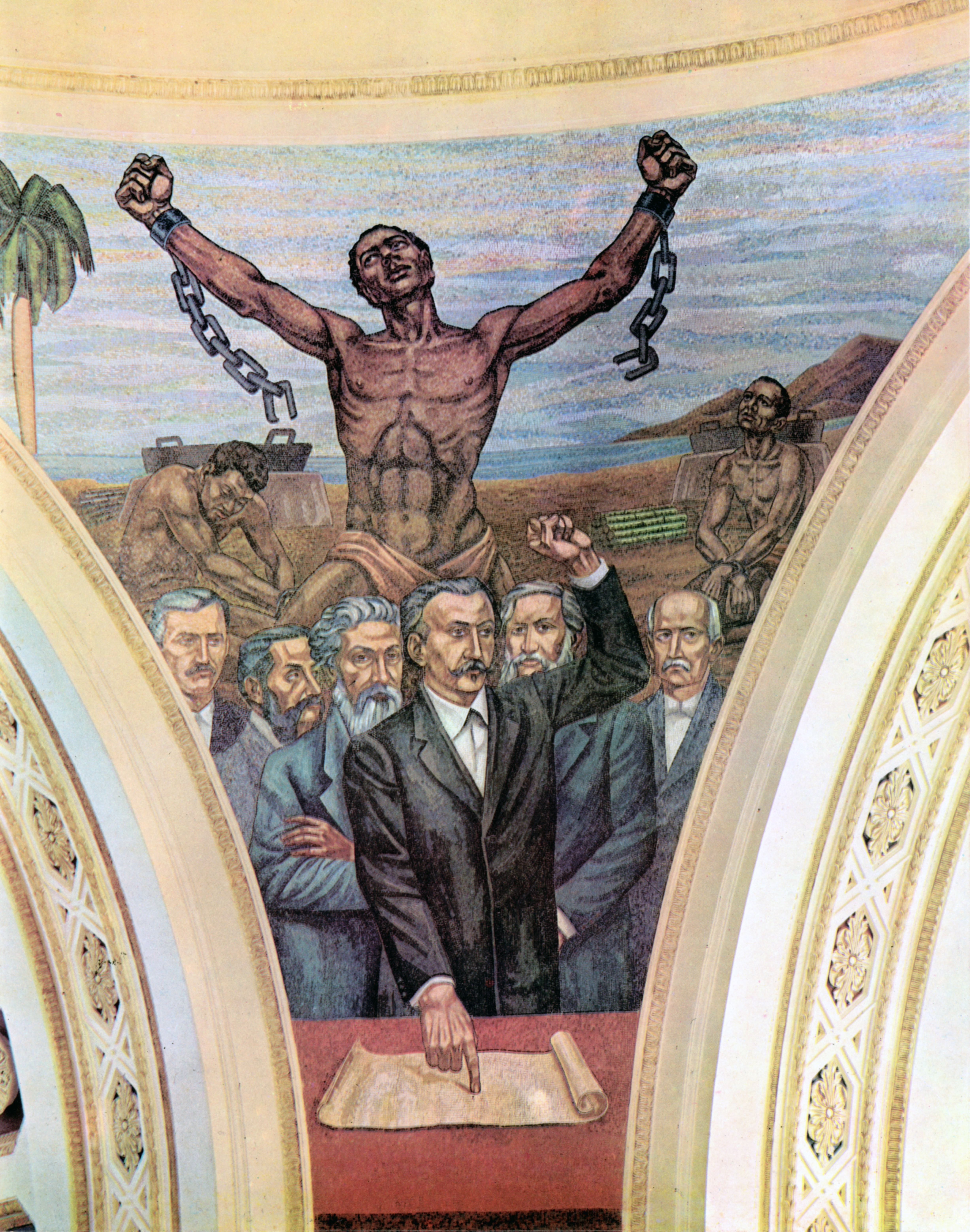

9. **The American Civil War and the Abolition of Slavery**: The breaking point arrived in 1861 when, beginning with South Carolina, “11 slave-state governments voted to secede from the United States,” uniting to form the Confederate States of America. While the majority of state governments remained steadfastly loyal to the Union, the lines were drawn, and the nation found itself irrevocably divided. The conflict ignited in April 1861, when the Confederacy launched its bombardment of Fort Sumter, signaling the tragic start of America’s deadliest war and a defining struggle for its very soul.

As the war raged, President Abraham Lincoln took a momentous step that would forever alter the course of American history and the very purpose of the conflict. On January 1, 1863, he issued the Emancipation Proclamation, a declaration that “many freed slaves joined the Union army,” transforming the Union’s fight from merely preserving the Union to also abolishing slavery. This act not only shifted the moral high ground but also provided a crucial boost to Union forces, as thousands of formerly enslaved individuals rallied to the cause of freedom.

The tide of war began to decisively turn in the Union’s favor following pivotal victories, including the 1863 Siege of Vicksburg and the Battle of Gettysburg. These Union triumphs crippled the Confederate war effort and demonstrated the Union’s growing military superiority. The war finally culminated with the Confederates’ surrender in 1865 after the Union’s victory in the Battle of Appomattox Court House, bringing about the nation’s reunification and the permanent, national abolition of slavery, fundamentally redefining American liberty.

10. **World War I and the Great Depression’s Impact**: The early 20th century thrust the United States onto the global stage in unprecedented ways. Though initially neutral, the U.S. eventually “entered World War I alongside the Allies in 1917,” playing a crucial role in “helping to turn the tide against the Central Powers” and marking its definitive emergence as a world player. Domestically, this era also saw significant social progress, with a “constitutional amendment granted nationwide women’s suffrage” in 1920, empowering half the population with the right to vote. Meanwhile, the advent of radio for mass communication and early television began to “transformed communications nationwide,” shrinking distances and connecting Americans in new ways.

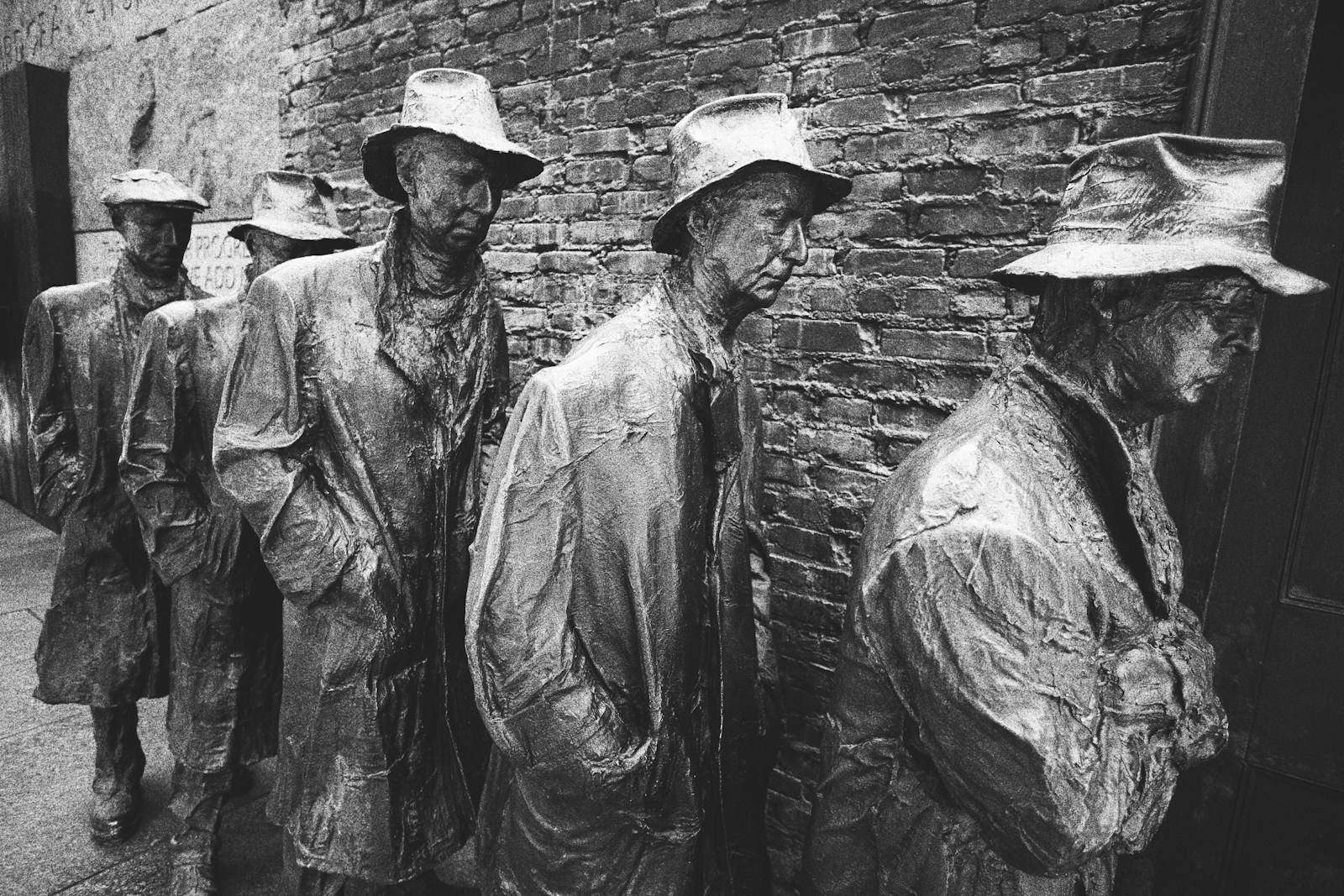

However, the prosperous Roaring Twenties came to an abrupt and devastating halt with “The Wall Street Crash of 1929,” which triggered the Great Depression. This economic calamity, which became “the largest economic contraction since the Great Depression” (referring to itself as the benchmark, highlighting its immense scale), plunged the nation into widespread unemployment, poverty, and despair. Homes were lost, businesses failed, and a deep sense of national crisis gripped the country, challenging the very foundations of American capitalism and social stability.

In response to this unparalleled crisis, President Franklin D. Roosevelt launched the ambitious New Deal plan, a sweeping series of initiatives characterized by its focus on “reform, recovery and relief.” This comprehensive package included “unprecedented and sweeping recovery programs and employment relief projects” designed to alleviate suffering and stimulate the economy, alongside “financial reforms and regulations” aimed at preventing future economic collapses. The New Deal dramatically expanded the role of the federal government in American life, setting precedents for social welfare and economic intervention that would shape the nation for decades to come.

And so, from revolutionary ideals to global supremacy, the story of the U.S. presidency is an ongoing saga of leadership navigating unprecedented challenges, making audacious decisions, and shaping the destiny of a nation. Each pivotal moment, from the forging of its foundational principles to its emergence as the world’s sole superpower, has added a crucial layer to the intricate tapestry of American history. These defining moments are not just historical footnotes; they are the very DNA of a nation that continues to evolve, adapt, and lead in a rapidly changing world, proving that the most profound measures of leadership are etched not in hypothetical scores, but in the indelible impact on generations.