The phenomenon of cults has long held a compelling grip on our collective imagination, conjuring vivid images of enigmatic figures, clandestine rituals, and often, tragic outcomes for those ensnared within their influence. It’s a subject that simultaneously sparks profound curiosity and deep concern, challenging our fundamental understanding of human autonomy and belief systems. How is it that individuals, seemingly ordinary, can be drawn into extreme ideologies, surrendering their sense of self to embark on a path of unquestioning devotion? This question sits at the heart of our ongoing fascination with cults, demanding a rigorous exploration of the psychological underpinnings that give rise to their unique allure and enduring power.

To truly grasp the intricate web of manipulation and control that defines these groups, we must delve into the very essence of what constitutes a cult and, crucially, what psychological traits and behaviors characterize the individuals who rise to lead them. Experts have dedicated decades to unraveling these complexities, revealing surprisingly consistent patterns across a diverse array of groups, whether their ideologies are religious, political, therapy-based, or centered on self-improvement. Understanding these dynamics is not merely an academic exercise; it is an essential endeavor for promoting awareness, fostering critical thinking, and ultimately protecting individuals and families from the potentially devastating harm caused by unscrupulous leaders.

Join us as we embark on an in-depth analytical journey, drawing on expert insights and research, to dissect the captivating yet disturbing psychology of cult leaders. We will explore the initial hooks that draw people in, the defining characteristics of those who wield such immense influence, and the subtle yet potent mechanisms through which they establish and maintain control over their followers. This exploration aims to shed light on how cults function, why they exert such profound power, and what makes their leaders such formidable puppet masters, leaving a lasting impression on the human psyche.

1. **Defining the ‘Cult’ Phenomenon: Beyond the Stereotypes**The term “cult” often conjures specific, dramatic images, but a clear, academic definition is essential for understanding the phenomenon. Janja Lalich, an expert in cultic studies and Professor Emerita of sociology at California State University, Chico, offers a widely accepted framework. She defines a cult as “a group or movement with a shared commitment to a usually extreme ideology that is usually embodied in a charismatic leader.” This definition highlights the core elements: an extreme belief system and a central, powerful figure.

Supplementing this, the APA Dictionary of Psychology provides a foundational baseline, stating that a cult is “a religious or quasi-religious group characterized by unusual or atypical beliefs, seclusion from the outside world, and an authoritarian structure.” The dictionary further elaborates that cults “tend to be highly cohesive, well organized, secretive, and hostile to nonmembers.” These characteristics collectively paint a picture of an insular, high-control environment where deviation from the leader’s prescribed path is met with resistance, and outside influences are actively rejected, emphasizing the deep isolation inherent in many cultic structures.

While the specific content or ideology of a cult can vary widely—from religious movements to political factions or even self-improvement schemes—these foundational definitions underscore commonalities. The shared commitment to an extreme ideology, coupled with the embodiment of that ideology in a charismatic leader, forms the bedrock upon which these groups are built. This understanding moves beyond superficial portrayals to identify the structural and ideological components that truly differentiate a cult from other social or religious organizations, setting the stage for deeper psychological analysis.

Read more about: They’re Strong, They’re Fierce, They’re ‘Muscle Mommies’: Exploring the Phenomenon Leaving Everyone In Awe

2. **The Primal Allure: Psychology Behind Cult Recruitment**The question of why individuals are drawn into cults is a profound one, and experts point to fundamental human needs as key drivers. Josh Hart, a professor of psychology at Union College, explains that people often seek out others or things to soothe their fears and anxieties, driven by a primal human need for comfort. Cults, in their initial phases, often skillfully tap into this desire by offering what many vulnerable individuals are desperately seeking in life. Research suggests that these elements have historically compelled hundreds of thousands globally to commit to various cults operating worldwide.

Hart elaborates on this allure, noting that cults actively “provide meaning, purpose and belonging.” In a world that can feel chaotic and isolating, the promise of a clear, confident vision, combined with a strong sense of community and shared purpose, can be incredibly appealing. They assert “the superiority of the group,” offering a comforting narrative of exclusivity and importance to those who feel marginalized or lost. This initial sense of acceptance and the provision of answers to life’s complex questions often form the first, crucial hooks that draw new members in, providing a psychological balm to their anxieties.

The leaders themselves play a critical role in this initial attraction. They typically present themselves as infallible, exuding confidence and an almost grandiose self-assurance. This charisma is a powerful magnet, drawing people who are craving peace, belonging, and security. Through participation in the group, followers often report gaining a sense of these very things, along with a renewed confidence. This powerful psychological exchange—where the leader offers a solution to profound personal needs—is a cornerstone of cult recruitment, leveraging human vulnerability for the group’s agenda.

3. **Lifton’s Framework: The Charismatic Leader as an Object of Worship**Psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton, a renowned expert in the psychology of zealotry, has provided an invaluable framework for understanding cult dynamics by outlining three primary characteristics. The first and arguably most pivotal characteristic is the presence of “a charismatic leader who becomes an object of worship beyond any meaningful accountability and becomes the single most defining element of the group and its source of truth, power, and authority.” This leader transcends typical leadership roles, becoming the unquestionable epicenter of the group’s existence.

In such an environment, the leader’s word becomes the ultimate reality, creating what Lifton refers to as “an alternate reality in which the truth is what the leader says it is because he said so.” This process signifies a profound shift where objective truth is supplanted by the leader’s pronouncements. There is no legitimate opposition to a cult leader; any challenge to their conduct or claims is invariably perceived as a hostile, bad-faith attack, not just on the leader, but on the entire group and its sacred ideology. This mechanism effectively stifles internal dissent and external scrutiny, reinforcing the leader’s absolute authority.

Consequently, the leader’s actions, no matter how egregious or demonstrably false, are rationalized and defended by the followers. The leader, in this perception, “cannot be wrong. They can only be wronged.” This unwavering belief system is crucial for maintaining the leader’s elevated status and the group’s cohesion. It creates a psychological bubble where the leader is infallible, deserving of absolute devotion, and where their personal agenda seamlessly merges with the supposed ‘common good’ of the followers, cementing their position as an untouchable object of worship.

4. **Lifton’s Framework: Indoctrination and Coercive Persuasion**The second critical characteristic in Robert Jay Lifton’s framework for cults is “a process of indoctrination, coercive persuasion, or thought reform that leads to group members doing things that are against their own best interest but serve the interest of the group leader.” This highlights the insidious nature of cultic influence, where an individual’s agency and self-preservation instincts are systematically undermined. The process is often gradual, subtle, and highly effective in reshaping a follower’s worldview and behavior.

This indoctrination often involves the creation of a filtered reality, meticulously curated by the group or its leader. Information that contradicts the cult’s narrative is dismissed or demonized, while only approved messages are reinforced. This constant stream of one-sided information, coupled with social pressure, slowly but surely erodes critical thinking abilities. Followers are conditioned to accept the group’s truths, even when they diverge significantly from external reality or their own prior beliefs. The goal is to establish a deep, unquestioning loyalty that supersedes personal judgment.

The result of such coercive persuasion is a profound shift in behavior, where individuals may engage in actions that, outside the cult context, would be unthinkable or self-destructive. These actions, whether they involve financial sacrifices, extreme personal commitments, or even violence, are rationalized as serving a higher purpose or the group’s collective good, all while ultimately benefiting the leader. The process is a testament to the power of psychological manipulation, illustrating how individuals can be persuaded to act against their own best interests under the intense influence of a cultic environment.

5. **Lifton’s Framework: Exploitation of Group Members**The third cornerstone of Robert Jay Lifton’s definition of a cult involves the “exploitation of group members by the leader and the ruling coterie.” This characteristic underscores the inherently predatory nature of cults, where the devotion, resources, and labor of followers are leveraged not for their genuine benefit, but primarily for the enrichment, power, or gratification of the leader and their inner circle. This exploitation can manifest in various forms, making it a pervasive and damaging aspect of cultic involvement.

Often, this exploitation involves significant financial demands. Followers may be compelled to surrender their money, assets, or even their entire livelihoods to the cult. This financial control can render members dependent on the group, making it exceptionally difficult for them to leave. Beyond finances, the exploitation can extend to labor, where members are expected to work tirelessly for the group with little to no compensation, often under harsh conditions, all under the guise of contributing to a shared, noble cause or the leader’s divine mission.

Furthermore, exploitation can be psychological, emotional, and even physical. Leaders may demand absolute obedience, controlling living arrangements, relationships, and even personal identity. The ultimate goal is to strip away an individual’s autonomy, making them entirely subservient to the leader’s will. This systematic exploitation, rooted in the leader’s self-aggrandizement, not only serves the leader’s material and ego-driven needs but also reinforces their power by demonstrating their complete control over the lives of their followers.

6. **The Architects of Control: Traits and Behaviors of Manipulative Leaders**Beyond Lifton’s foundational characteristics, studies of cult leader psychology reveal a surprisingly consistent pattern of beliefs and actions across various groups. One of the most striking commonalities among manipulative leaders is a remarkable ability to exploit others, leveraging their authority to maintain absolute control. These traits often include charismatic communication, which makes them persuasive speakers who inspire immense trust and loyalty. Their adeptness at connecting emotionally with followers allows them to forge strong bonds, drawing individuals into their orbit through sheer force of personality.

Coupled with this charisma is an unwavering authoritarian control. These leaders demand absolute obedience, employing a range of tactics—from fear and isolation to outright punishment—to ensure compliance. Dissent is rarely tolerated within their carefully constructed environments, and their authority remains unchallenged. This creates a stifling atmosphere where critical thinking is suppressed, and questioning the leader’s directives is viewed as an act of betrayal, thus solidifying their grip over the group. The leader’s word becomes law, and deviation carries severe social or psychological consequences.

Furthermore, manipulative cult leaders frequently present a grandiose vision. They often position themselves as possessing a unique mission, divine insight, or extraordinary knowledge, convincing their followers that they are essential to achieving some higher purpose. This elevated self-perception, combined with their ability to articulate a compelling, often world-changing, narrative, creates an environment of dependency. Followers come to believe that only through their leader can this grand vision be realized, binding them to the leader and their self-serving agenda in a powerful, emotionally charged way.

7. **The Dark Duo: Narcissism and Charisma as Key Factors in Leader Psychology**Perhaps one of the most striking and dangerous aspects of cult leader psychology is the potent interplay between profound personal narcissism and a specific, often dark, form of charisma. While charisma provides the magnetic appeal that draws people in and inspires loyalty, the underlying narcissistic traits of these leaders fuel their insatiable need for excessive admiration, control, and a constant validation of their exaggerated sense of self-importance. This combination creates a powerful, almost irresistible force that can ensnare even psychologically resilient individuals.

Many cult leaders exhibit classic traits of Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD), including an inflated sense of self-importance, a pervasive need for admiration, and a profound lack of empathy for others. This internal architecture allows them to rationalize their exploitative behavior, as they genuinely believe their actions are justified and that others exist primarily to serve their needs. They are often unstable, self-absorbed, paranoid, and notably out of touch with reality, yet their charisma masks these deeper pathologies, presenting an illusion of strength and wisdom to their followers. Internally, their fragile self-structure is propped up by the adoration and obedience they extract.

This charismatic authority provides the magnetic appeal that draws individuals to them, often viewing the leader as a larger-than-life figure endowed with wisdom or power unattainable by ordinary people. This dynamic fosters a deep sense of dependency, particularly for psychologically and emotionally vulnerable individuals, making it incredibly difficult for them to consider leaving the cult environment. The leader’s charisma, therefore, becomes a tool for narcissistic supply, ensuring a steady stream of admiration and devotion that reinforces their grandiose delusions and maintains their control over the lives of their followers.” , “_words_section1”: “1997

The initial hooks that draw individuals into a cult are often subtle, leveraging innate human desires for connection and security. However, once inside, the methods employed to solidify control become far more intricate and psychologically sophisticated. These tactics aim to dismantle an individual’s autonomy and replace it with an unwavering devotion to the leader and the group’s agenda, often leading to profound and lasting psychological consequences. Understanding these advanced mechanisms is crucial for comprehending the enduring power that cult leaders wield.

Our journey into the psychology of cult leaders now turns to the specific, often insidious, techniques they employ to maintain their grip, the devastating impact these methods have on their followers, and a contemplation of the broader societal implications, including a look at some of history’s most notorious examples.

8. **The Subtle Trap of Cognitive Dissonance**One of the most powerful psychological tools at a cult leader’s disposal is the manipulation of cognitive dissonance. This theory, introduced in the late 1950s, posits that individuals experience psychological discomfort when confronted with facts or ideas that contradict their deeply held beliefs, values, or actions. To alleviate this uneasiness, people are inherently driven to resolve the contradiction, often by rationalizing or altering their perceptions to align with the group’s narrative, rather than confronting the unsettling truth.

In a cult setting, this mechanism becomes an insidious trap. As Janja Lalich explains, cognitive dissonance often “keeps you trapped as each compromise makes it more painful to admit you’ve been deceived.” Every small concession, every questionable act performed in the group’s name, creates a deeper psychological investment, making it increasingly difficult for members to acknowledge the deception or the harm being inflicted. The cult actively employs “both formal and informal systems of influence and control” to ensure that members remain obedient, with “little tolerance for internal disagreement or external scrutiny,” thereby perpetually reinforcing the leader’s constructed reality.

9. **Orchestrating Obedience: The Erosion of Free Will**The factor of obedience plays a profound role in cult dynamics, capitalizing on a natural human inclination to follow orders and conform to the actions of those around them. Within the insular environment of a cult, critical thinking, independent questioning, and individual judgment are not merely discouraged but actively “frowned upon,” systematically stifling any nascent dissent. Conversely, “absolute faith is rewarded,” creating a powerful incentive structure that promotes unquestioning adherence to the leader’s directives.

This is not a benign process; it is a deliberate and often brutal campaign to dismantle an individual’s sense of self. “Guilt, shame and fear are also constantly wielded to slowly strip away an individual’s identity,” reducing them to a state of heightened vulnerability and malleability. In an environment where “full obedience to leaders is required,” fundamental human rights such as “free thinking, free will and free speech are limited,” ensuring that members become extensions of the leader’s will. This systematic erosion of identity transforms followers into instruments serving the leader’s agenda, which experts note is often driven by “narcissistic and authoritarian streaks” and motivations like “money, sex or power (perhaps all three).”

10. **Love Bombing and Strategic Isolation: Crafting an Echo Chamber**The initial phase of cult recruitment often involves a manipulative tactic known as “love bombing.” This technique entails “showering potential recruits with affection, attention and praise to create a sense of belonging and loyalty.” For individuals feeling lonely, vulnerable, or seeking meaning, this overwhelming display of acceptance and validation can be incredibly potent, making them believe they have found the genuine connection they desperately crave. It is a critical step in the early stages of indoctrination, establishing a sense of security and trust before any demands are made.

Once this initial bond is forged and trust is established, cult leaders swiftly move to implement strategic isolation. They will “cut off followers from friends, family and external sources of information, creating an echo chamber where the leader’s voice is dominant.” This systematic separation serves to dismantle existing support systems and prevent critical external perspectives from penetrating the cult’s carefully constructed narrative. By “slowly remaking their identities to suit the group,” and sometimes even compelling them to “surrender their money, belongings, and bodies,” leaders foster an environment of complete dependency. The individual, deprived of external reality checks and fearing the loss of their newfound community, becomes increasingly reliant on the cult, further solidifying the leader’s control.

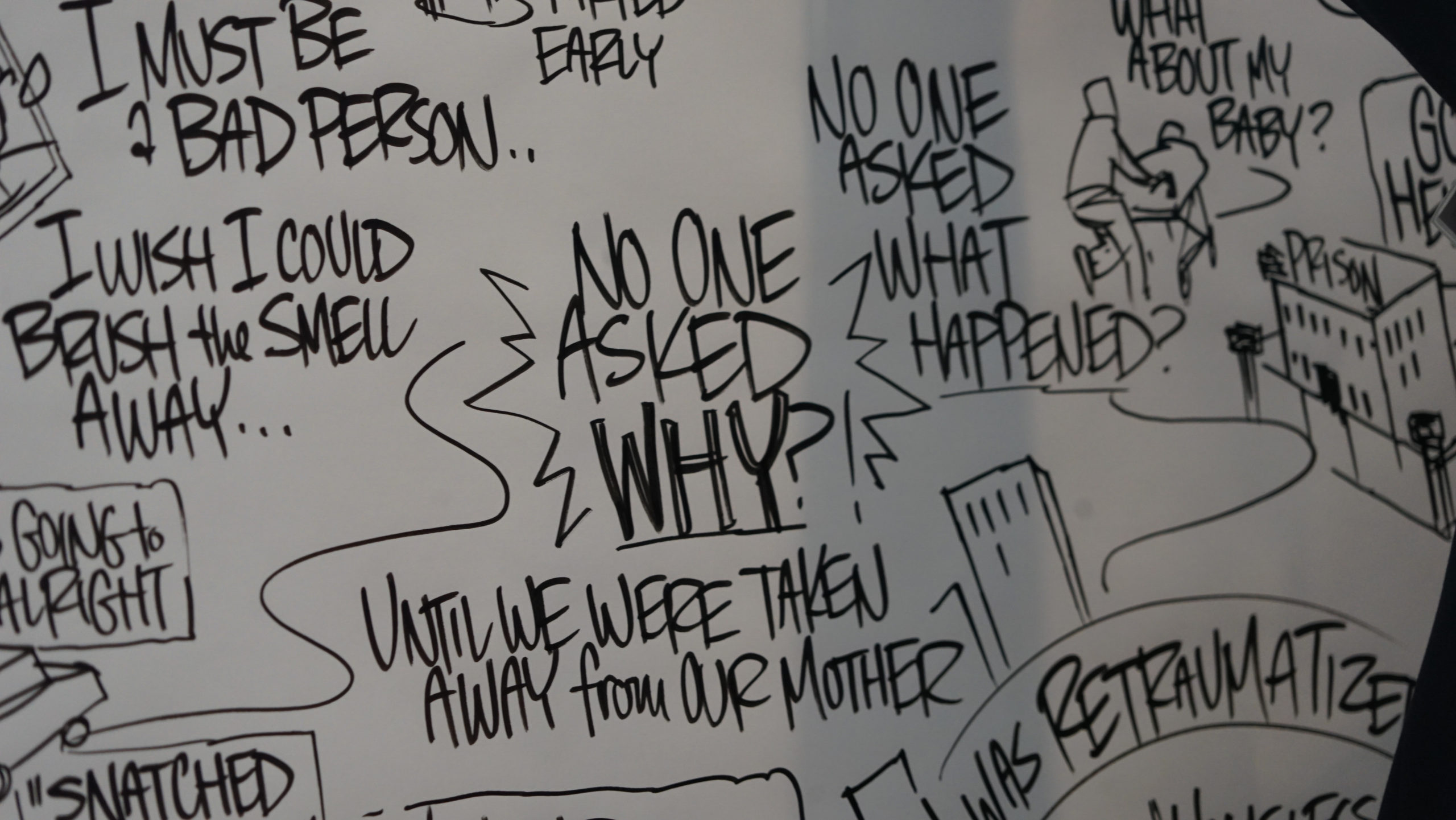

11. **The Profound Psychological Scars: Emotional Dependency, Trauma, and PTSD**The influence of a manipulative cult leader extends far beyond surface-level control, leaving deep and often indelible psychological harm. Many followers develop an intense “emotional dependency” on the leader, coming to view them as their sole “source of validation and purpose.” This profound reliance makes the prospect of leaving the group seem insurmountable, as it would mean abandoning their perceived identity, support system, and the very meaning they have come to attribute to their existence. The damage inflicted upon “psychologically vulnerable members” can be immense, leaving “scars that might last for the rest of their lives, even years after they leave the cult.”

Indeed, the long-term consequences are severe. Those who manage to break free from cult environments frequently “suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), grappling with feelings of guilt, shame and fear long after the experience ends.” The experience of having one’s autonomy stripped away, one’s reality systematically distorted, and often enduring various forms of abuse and exploitation, creates a complex web of trauma. This trauma can manifest as ongoing mental distress, difficulty forming healthy relationships, and a persistent struggle to reintegrate into mainstream society, underscoring the devastating and lasting impact of cultic involvement.

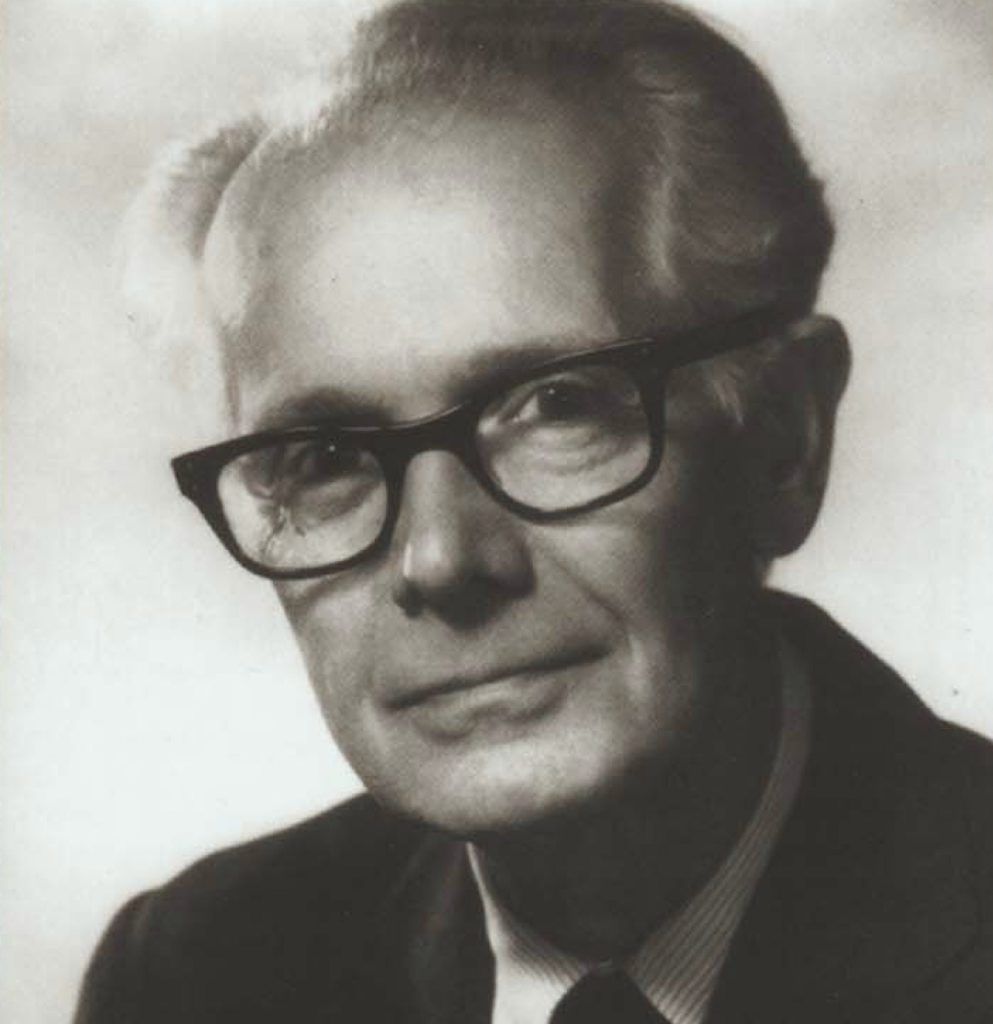

12. **Unpacking Vulnerability: The Self-Psychology of Heinz Kohut**To understand *why* individuals are susceptible to cultic allure, we can turn to the framework of psychoanalyst Heinz Kohut, who emphasized the “motivational primacy of self-experience.” Kohut proposed that when a child’s early environment fails to provide the necessary relational support, it can lead to “high disintegration anxiety.” In response, individuals may mobilize “pathological behaviors” as desperate attempts to stabilize a fragile self-structure. These behaviors, often seen as efforts to restore a sense of self-cohesion, can be understood as reactions to the threat of self-disintegration.

This individual dynamic can be extrapolated to the societal realm, as “individuals live in groups and create societies.” Just as a vulnerable person might seek a group to shore up their identity, a “threatened group may rally behind a leader’s idealized persona to shore up its besieged identity.” This phenomenon is particularly plausible when a large demographic feels abandoned or disenfranchised by cultural, social, and economic shifts. For example, some members of groups feeling their livelihoods, status, and cultural hegemony undermined may find in a charismatic figure “a voice for their grievances, a balm for their ego injury, a totem for their rage.” Cultist devotion can thus offer a powerful, albeit pathological, solution to feelings of inferiority, vulnerability, and disenfranchisement.

However, Kohut also observed that “self-disintegration involves ‘narcissistic rage,’ which Kohut defined as aggression aimed at others who threaten or have damaged the self.” This powerful, destructive rage can drive both individuals and groups to “shed traditional beliefs and accepted groups and opt for more radical ones.” The cult leader then becomes a potent symbol for the group’s anger at perceived negative or dismissive responses from society at large. The profound danger, as Kohut noted, is that the “most powerful human destructiveness… is encountered, not in the form of wild, regressive, and primitive behavior, but in the form of orderly and organized activities in which the perpetrators’ destructiveness is alloyed with absolute conviction about their greatness and with their devotion to archaic omnipotent figures.”

13. **Echoes of Devotion and Despair: Notorious Cults in History**The annals of history are unfortunately replete with cautionary tales of cults and their destructive leaders, serving as stark reminders of the profound psychological power wielded over followers. One of the most infamous examples is Jim Jones’ Peoples Temple, which began as a seemingly progressive civil rights organization. However, under Jones’ increasingly authoritarian and paranoid leadership, the group relocated to a remote commune in Guyana, known as “Jonestown.” In 1978, amidst escalating scrutiny, Jones orchestrated a mass suicide, ordering his followers to drink a “cyanide-laced drink.” A staggering “909 died, including children,” many forced at gunpoint, making it one of the largest single losses of American civilian life in a non-natural disaster event.

Another chilling example is David Koresh and the Branch Davidians. Koresh, who believed himself to be the Messiah and all women his “spiritual wives,” led his apocalyptic group into a sprawling compound in Waco, Texas. In 1993, a government raid on the compound, prompted by reports of weapons stockpiling, devolved into a 51-day standoff that ultimately ended in a fiery tragedy, leaving “more than 80 dead.” Similarly, Marshall Applewhite’s Heaven’s Gate cult culminated in a mass suicide in 1997, as 39 members, convinced an extraterrestrial spacecraft behind the Hale-Bopp comet would transport them to a “higher level of existence,” ingested a lethal cocktail and placed plastic bags over their heads.

These high-profile cases, alongside others like Charles Manson’s “family” of runaways who committed brutal murders to ignite a race war, and Keith Raniere’s Nxivm, which outwardly presented as a self-help organization but secretly operated as a sex cult that branded and blackmailed women, highlight the diverse yet consistently destructive paths of cults. The tragic outcomes underscore the dangers of unchecked charismatic authority and the profound vulnerabilities that manipulative leaders exploit, leading followers to commit actions they would never have contemplated in their former lives, often with fatal consequences.

14. **The Elusive Boundary: Cults, Religion, and Societal Safeguards**The distinction between a cult and a religion is a “thorny topic,” often contentious and subjective, and is one of the most complex societal implications of these groups. As Janja Lalich clarifies, “while many religions began as cults,” some, over time, “integrated into the fabric of the larger society as they grew.” The divergence often lies in control; while religions may offer guidance and support, a cult typically “separates its members from others and seeks to directly control financial assets and living arrangements,” creating a high-control, insular environment.

Further complicating matters is the legal landscape. Because cults frequently operate under the guise of religious organizations, “cults are protected under laws governing religious freedom,” making it “tricky to legally prosecute cults and their leaders.” This protection often means that even when exploitative or abusive practices are evident, legal intervention is challenging. Moreover, the subjective experience of members themselves—where “some cult members may insist they’re involved of their own free will and are living happy lives”—adds another layer of complexity to public perception and intervention efforts.

Ultimately, the enduring “fascination of cults lies in their complex interplay of psychological, social and cultural factors,” ensuring they “will undoubtedly continue to fascinate and puzzle us for generations.” The dynamics we observe in cults, however, are not confined to isolated groups; they can, and do, “play out in a variety of other settings such as political systems, authoritarian organisations, toxic families and one-on-one relationships as well.” Therefore, understanding the psychology of the puppet master—the traits of the leader, the tactics of control, and the vulnerabilities exploited—remains a vital endeavor, not just for protecting individuals from explicit cults, but for fostering critical thinking and safeguarding against unchecked authority in all its forms, wherever it may arise. The ability to discern and resist such manipulation is perhaps our most potent defense against being led astray.