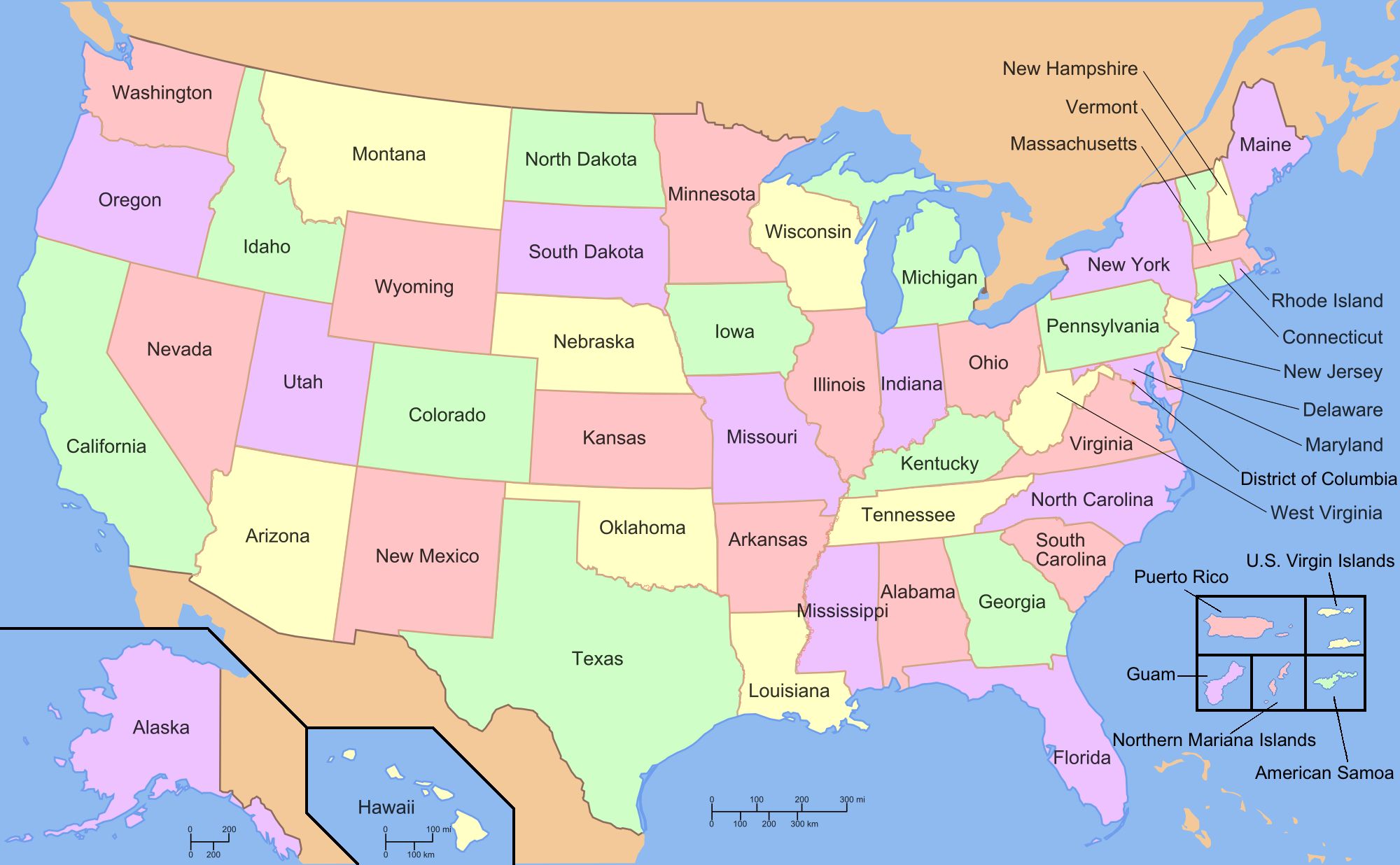

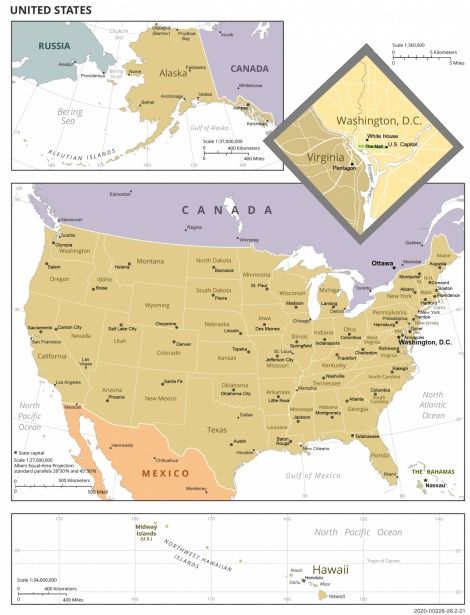

The United States of America, often referred to simply as the United States or America, stands as a prominent nation primarily situated in North America. This vast federal republic encompasses 50 states and a distinct federal capital district, Washington, D.C. Its expansive geography includes the 48 contiguous states, which share borders with Canada to the north and Mexico to the south, alongside the semi-exclave of Alaska in the northwest and the volcanic archipelago of Hawaii nestled in the Pacific Ocean. Beyond its continental and insular states, the U.S. also asserts sovereignty over five major island territories and various uninhabited islands spread across Oceania and the Caribbean, contributing to its status as a megadiverse country with the world’s third-largest land area and third-largest population, currently exceeding 340 million people.

The journey of this nation traces back over 12,000 years, with Paleo-Indians migrating from North Asia to North America, laying the foundations for various early civilizations. European exploration and colonization began in earnest with Spanish efforts, establishing Spanish Florida in 1513, marking the first European colony within what is now the continental United States. British colonization soon followed, notably with the 1607 settlement of Virginia, which became the first of the eventual Thirteen Colonies. This period also saw the forced migration of enslaved Africans, whose labor force became integral to sustaining the plantation economies of the Southern Colonies.

Growing tensions between the colonies and the British Crown, primarily concerning taxation and a perceived lack of parliamentary representation, ignited the American Revolution. This pivotal conflict ultimately led to the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, a document that formally asserted the colonies’ desire for self-governance. The victory in the Revolutionary War, fought between 1775 and 1783, secured international recognition of U.S. sovereignty, fueling a wave of westward expansion that unfortunately dispossessed many native inhabitants from their ancestral lands.

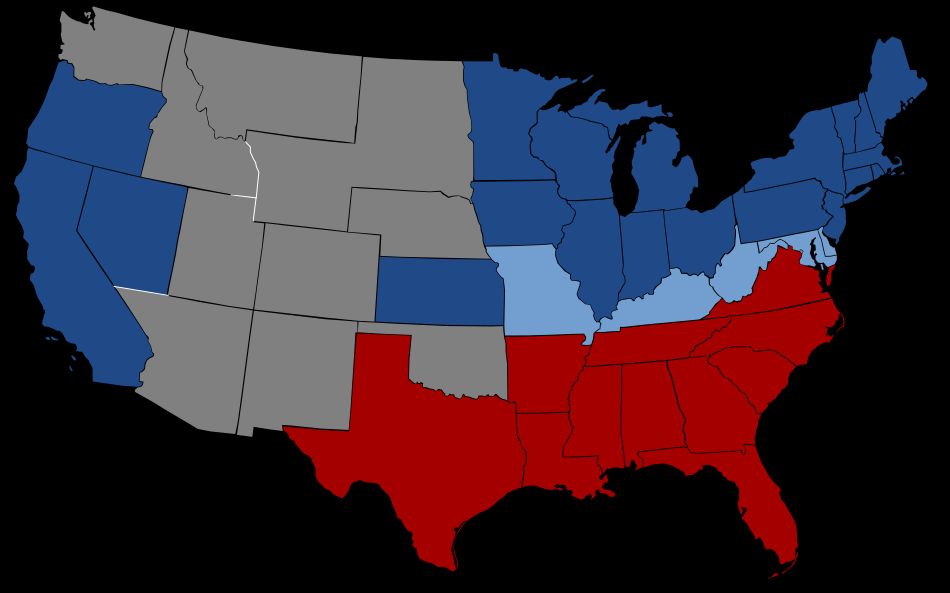

As the nation grew and more states were admitted to the Union, a profound North–South division over the institution of slavery deepened. This fundamental disagreement culminated in the American Civil War from 1861 to 1865, as the Confederate States of America attempted secession from the Union. The United States’ victory and subsequent reunification led to the national abolition of slavery, a transformative moment in the country’s history. By the turn of the 20th century, the U.S. had firmly established itself as a great power, a status that was further solidified after its involvement in World War I, marking its growing influence on the global stage.

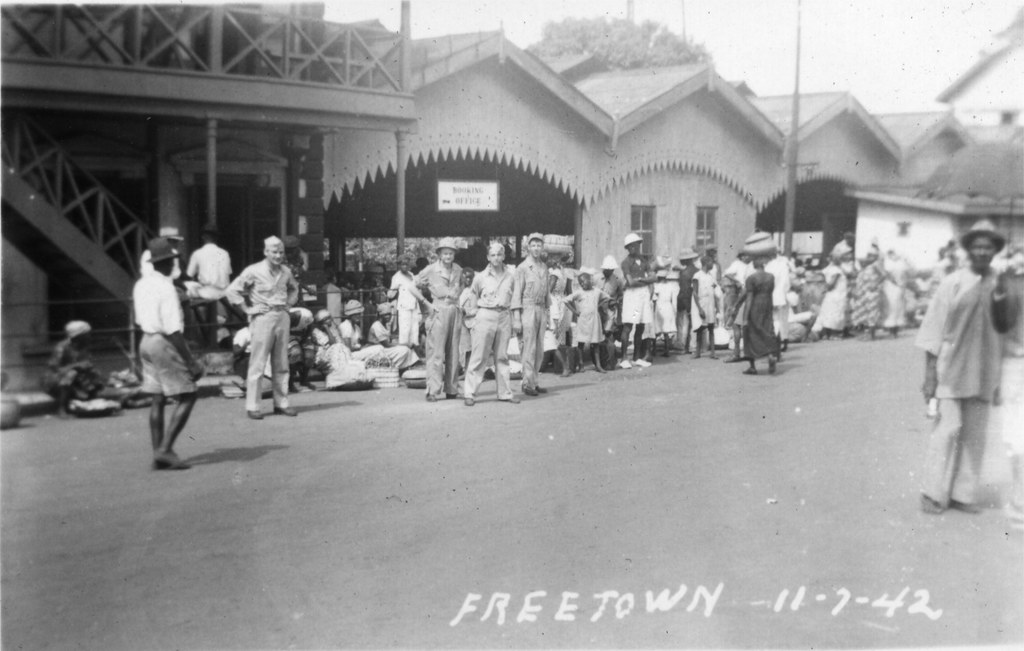

The attack on Pearl Harbor by Japan in 1941 propelled the United States into World War II. The aftermath of this global conflict fundamentally reshaped the world order, leaving the U.S. and the Soviet Union as rival superpowers, locked in an ideological and geopolitical struggle known as the Cold War. This period of intense competition for international influence persisted until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, at which point the United States emerged as the world’s sole superpower, underscoring its unparalleled global standing.

The U.S. national government operates as a presidential constitutional federal republic and a representative democracy, structured around three distinct branches: legislative, executive, and judicial. This tripartite system, headquartered in Washington, D.C., is designed with a separation of powers and a robust system of checks and balances, intended to prevent any single branch from becoming supreme. The bicameral national legislature, known as the U.S. Congress, is comprised of the House of Representatives, where representation is based on population, and the Senate, which ensures equal representation for each state.

Federalism remains a core principle of American governance, granting substantial autonomy to its 50 states. Additionally, 574 Native American tribes possess sovereignty rights, with 326 Native American reservations existing within the country’s borders. Since the 1850s, the Democratic and Republican parties have predominantly shaped American politics, their platforms reflecting a democratic tradition deeply inspired by the American Enlightenment movement. This political landscape, characterized by robust debate and participation, reflects the enduring values that underpin the nation’s governance.

Read more about: The United States: A Complex Legacy of Discord and Unity, Shaping a Nation’s Evolving Identity

As a developed country, the United States consistently ranks high in economic competitiveness, innovation, and higher education, showcasing its dynamic economy. Its economic output accounts for over a quarter of the nominal global total, having maintained its position as the world’s largest economy since approximately 1890. While recognized as the wealthiest country with the highest disposable household income per capita among OECD members, it also contends with one of the most pronounced wealth inequalities among those nations, a complex facet of its economic structure. Shaped by centuries of diverse immigration, the culture of the U.S. is richly varied and globally influential, contributing significantly to worldwide trends in arts, entertainment, and lifestyle.

In terms of military strength, the U.S. boasts one of the strongest militaries globally, accounting for more than a third of total global military spending, and holds the status of a recognized nuclear state. Its active membership in numerous international organizations signifies its major role in global political, cultural, economic, and military affairs, underscoring its profound impact on the international stage. The nation’s etymology itself offers a glimpse into its historical foundation, with documented use of the phrase “United States of America” dating back to January 2, 1776, in a letter from Stephen Moylan to Joseph Reed, seeking assistance for the Revolutionary War effort from Spain. The first known public usage appeared in an anonymous essay published in The Virginia Gazette on April 6, 1776, highlighting the nascent identity of the emerging nation.

Thomas Jefferson included “United States of America” in a rough draft of the Declaration of Independence sometime on or after June 11, 1776, a foundational document adopted by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776. The terms “United States” and its initialism “U.S.,” alongside “USA,” are common short names for the country, used as nouns or adjectives, and are established terms throughout the U.S. federal government. Colloquial shortenings like “The States” are also common, particularly from abroad, with “stateside” as the corresponding adjective or adverb.

The name “America” itself derives from the feminine form of “Americus Vesputius,” the Latinized name of Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci. German cartographers Martin Waldseemüller and Matthias Ringmann first used it as a place name in 1507. Vespucci’s significant contribution was his proposal that the West Indies, discovered by Christopher Columbus in 1492, were part of a previously unknown landmass rather than the eastern limit of Asia. In English, the term “America” typically refers specifically to the United States, although “the Americas” describes the totality of the North and South American continents.

Read more about: Ross E. Rowland Jr., Visionary Who United Wall Street Fortune with Steam-Powered Grandeur, Dies at 85

The history of the United States unfolds from its indigenous roots, with the first inhabitants migrating from Siberia over 12,000 years ago, eventually giving rise to sophisticated cultures like the Clovis culture, which appeared around 11,000 BC. Post-archaic period cultures, such as the Mississippian in the Midwest, East, and South, and the Algonquian in the Great Lakes region and along the Eastern Seaboard, alongside the Hohokam and Ancestral Puebloans in the Southwest, demonstrated advanced societal development, including agriculture and architecture. Native population estimates before European arrival ranged from 500,000 to nearly 10 million, indicating a vibrant and widespread presence.

European exploration and colonization began with Christopher Columbus’s expeditions for Spain in 1492, leading to Spanish-speaking settlements and missions from present-day Puerto Rico and Florida to New Mexico and California. Spanish Florida, chartered in 1513, was the first Spanish colony in the continental U.S., with Saint Augustine founded as its first permanent town in 1565 after several earlier settlement failures. France also established settlements, though many were abandoned or destroyed, with permanent ones emerging much later along the Great Lakes, the Mississippi River, and the Gulf of Mexico. Early European colonies further included the thriving Dutch New Nederland (present-day New York, settled 1626) and the smaller Swedish New Sweden (present-day Delaware, settled 1638).

British colonization along the East Coast commenced with the Virginia Colony in 1607 and the Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts in 1620. Precedents for representative self-governance and constitutionalism were established through documents like the Mayflower Compact and the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut, shaping the political development of the American colonies. While conflicts with Native Americans were present, there was also trade, exchanging European tools for food and animal pelts, though relations spanned a spectrum from cooperation to warfare and massacres. Colonial authorities often sought to assimilate Native Americans into European lifestyles, including conversion to Christianity, and along the eastern seaboard, African slaves were trafficked through the Atlantic slave trade.

Read more about: Texas’s Shifting Sands of Power: Unpacking the Complex Forces Shaping the Lone Star State’s Political Destiny

The original Thirteen Colonies, which would later form the United States, were governed as British Empire possessions by Crown-appointed governors, despite local governments holding elections open to most white male property owners. The colonial population experienced rapid growth from Maine to Georgia, eclipsing Native American populations. By the 1770s, natural population increase meant only a small minority of Americans were born overseas. The geographical distance from Britain fostered the entrenchment of self-governance, while the First Great Awakening, a series of Christian revivals, stimulated colonial interest in guaranteed religious liberty.

Following their victory in the French and Indian War, Britain began to exert greater control over colonial affairs, triggering political resistance. A primary grievance was the denial of colonists’ rights as Englishmen, particularly the right to representation in the British government that taxed them. To demonstrate their dissatisfaction, the First Continental Congress met in 1774 and passed the Continental Association, an effective boycott of British goods. The British attempt to disarm the colonists sparked the American Revolutionary War with the 1775 Battles of Lexington and Concord.

The Second Continental Congress appointed George Washington commander-in-chief of the Continental Army and tasked a committee, including Thomas Jefferson, to draft the Declaration of Independence. Adopted on July 4, 1776, two days after passing the Lee Resolution for independence, the Declaration articulated American Revolution values such as liberty, inalienable individual rights, and the sovereignty of the people. These ideals supported republicanism, rejecting monarchy, aristocracy, and hereditary political power, emphasizing civic virtue and vilifying political corruption. The Founding Fathers, including Washington, Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, James Madison, and Thomas Paine, drew inspiration from Classical, Renaissance, and Enlightenment philosophies.

Though in practical effect since its drafting in 1777, the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union was formally ratified in 1781, establishing a decentralized government that operated until 1789. American sovereignty was internationally recognized by the Treaty of Paris (1783) after the British surrender at the siege of Yorktown in 1781. This treaty granted the U.S. territory stretching west to the Mississippi River, north to present-day Canada, and south to Spanish Florida. The Northwest Ordinance (1787) set a crucial precedent for territorial expansion through the admission of new states, rather than the enlargement of existing ones.

Read more about: Innovation Nation: America’s Enduring Drive for Pioneering Technology and Unrivaled Global Influence

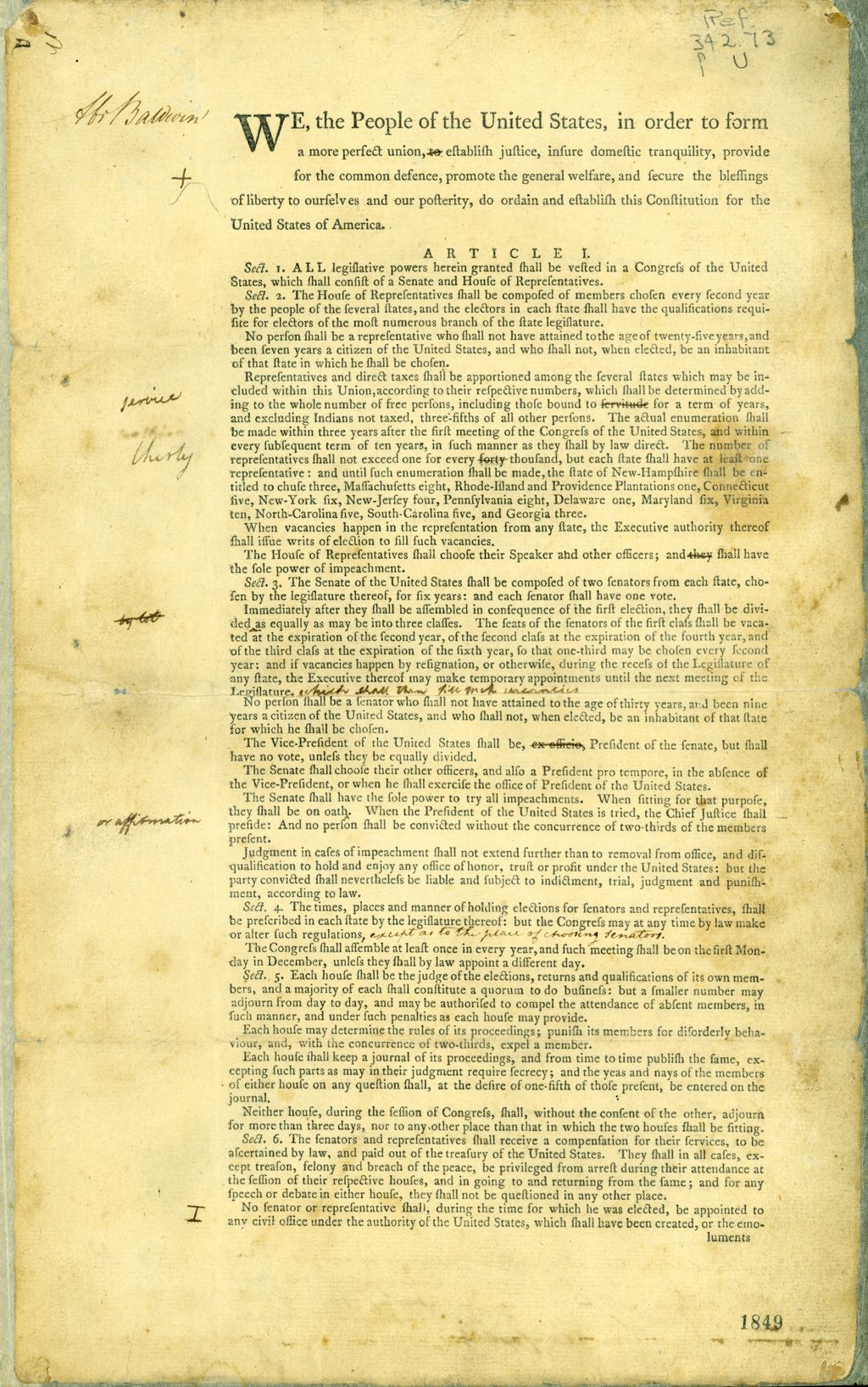

To overcome the Articles’ limitations, the U.S. Constitution was drafted at the 1787 Constitutional Convention, taking effect in 1789. This document established a federal republic governed by three separate branches, ensuring a system of checks and balances. George Washington was elected the first president under the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights was adopted in 1791 to address concerns about the centralized government’s power. Washington’s resignation as commander-in-chief and refusal of a third presidential term established precedents for civil authority’s supremacy and peaceful power transfer.

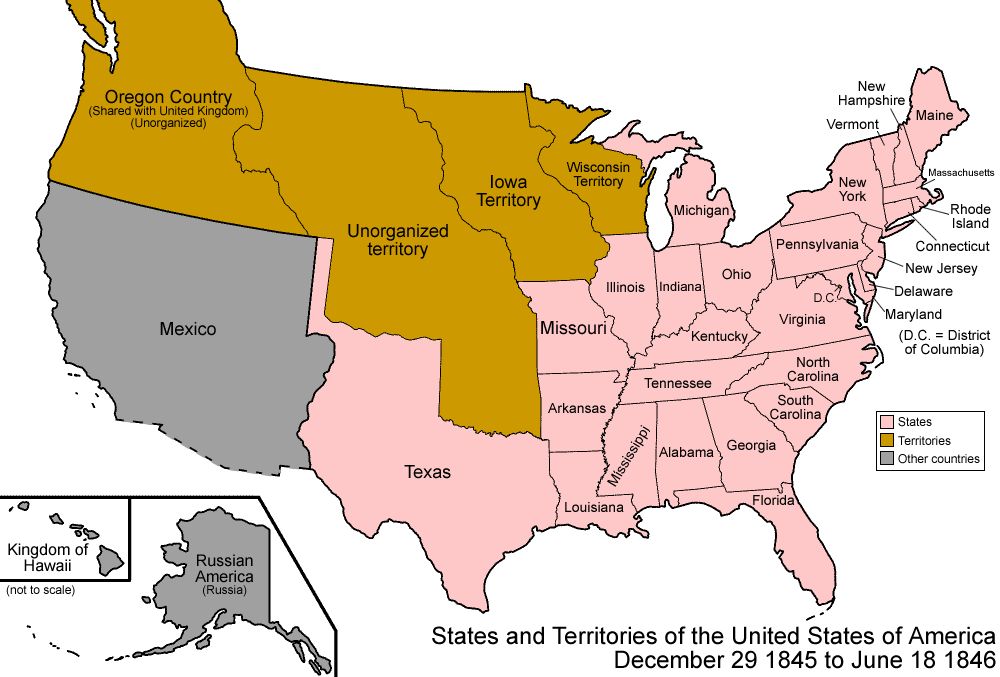

In the late 18th century, American settlers significantly expanded westward, many driven by a sense of manifest destiny. The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 from France nearly doubled the United States’ territory. Lingering issues with Britain led to the War of 1812, which concluded in a draw, and Spain ceded Florida and its Gulf Coast territory in 1819. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 attempted to balance the expansion of slavery by admitting Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state, generally prohibiting slavery in other Louisiana Purchase lands north of the 36°30′ parallel.

As Americans pushed further into Native American territories, the federal government implemented policies of Indian removal or assimilation, notably through the Indian Removal Act of 1830 under President Andrew Jackson. This policy resulted in the devastating Trail of Tears (1830–1850), forcibly displacing an estimated 60,000 Native Americans from east of the Mississippi River to lands far west, causing 13,200 to 16,700 deaths. This settler expansion and influx of Indigenous peoples from the East also spurred the American Indian Wars west of the Mississippi.

Read more about: Beyond the Basics: Dangerous Survival Myths and Other Misconceptions Experts Wish You’d Stop Believing

The United States annexed the Republic of Texas in 1845, and the 1846 Oregon Treaty secured U.S. control of the present-day American Northwest. A dispute with Mexico over Texas led to the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). Following a U.S. victory, Mexico recognized U.S. sovereignty over Texas, New Mexico, and California in the 1848 Mexican Cession, which also included future states like Nevada, Colorado, and Utah. The California gold rush of 1848–1849 spurred a massive migration to the Pacific coast, intensifying confrontations with Native populations, including the California genocide, which lasted into the mid-1870s. Additional western territories and states were subsequently created.

During the colonial period, slavery was legal in the American colonies, becoming the main labor force for the large-scale, agriculture-dependent economies of the Southern Colonies. The practice faced significant questioning during the American Revolution and, spurred by an active abolitionist movement that reemerged in the 1830s, Northern states began enacting laws to prohibit slavery within their boundaries. Concurrently, support for slavery strengthened in Southern states, where inventions like the cotton gin (1793) made it immensely profitable for Southern elites. Throughout the 1850s, sectional conflict over slavery was inflamed by national legislation and Supreme Court decisions.

In Congress, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 mandated the forcible return of enslaved individuals to their owners from non-slave states, while the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 effectively undermined the anti-slavery provisions of the Missouri Compromise. The Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision of 1857 ruled against a slave brought into non-slave territory, simultaneously declaring the entire Missouri Compromise unconstitutional. These events exacerbated North-South tensions, culminating in the American Civil War (1861–1865). Starting with South Carolina, 11 slave-state governments seceded in 1861 to form the Confederate States of America, while all other state governments remained loyal to the Union.

Read more about: Texas’s Shifting Sands of Power: Unpacking the Complex Forces Shaping the Lone Star State’s Political Destiny

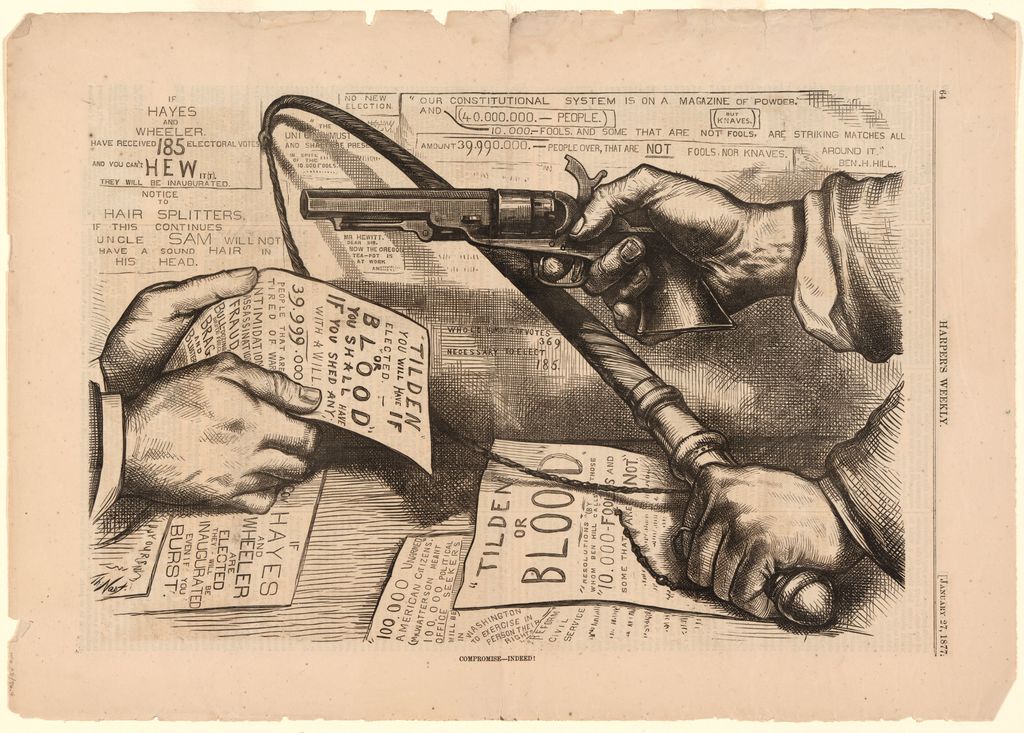

This compromise resolved the electoral crisis following the 1876 presidential election and led President Rutherford B. Hayes to reduce the role of federal troops in the South. Immediately, the Redeemers began evicting the Carpetbaggers and quickly regained local control of Southern politics in the name of white supremacy. African Americans endured a period of heightened, overt racism following Reconstruction, often called the nadir of American race relations. A series of Supreme Court decisions, including Plessy v. Ferguson, weakened the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, allowing Jim Crow laws in the South, “sundown towns” in the Midwest, and segregation nationwide to persist, later reinforced by redlining policies.

An explosion of technological advancement, coupled with the exploitation of cheap immigrant labor, fueled rapid economic expansion during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, enabling the United States to surpass the combined economies of England, France, and Germany. This period fostered the concentration of power among prominent industrialists, largely through the formation of trusts and monopolies that stifled competition. Tycoons spearheaded the nation’s expansion in the railroad, petroleum, and steel industries, and the United States emerged as a pioneer in the automotive industry. These changes resulted in significant increases in economic inequality, widespread slum conditions, and social unrest, creating a fertile environment for labor unions and socialist movements to flourish. This period eventually transitioned into the Progressive Era, characterized by significant social and political reforms.

In a series of territorial acquisitions around the turn of the century, pro-American elements in Hawaii overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy, leading to the islands’ annexation in 1898. That same year, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam were ceded to the U.S. by Spain after its defeat in the Spanish–American War. (The Philippines gained full independence from the U.S. on July 4, 1946, after World War II, while Puerto Rico and Guam remain U.S. territories.) American Samoa was acquired in 1900 following the Second Samoan Civil War, and the U.S. Virgin Islands were purchased from Denmark in 1917, further expanding the nation’s global footprint.

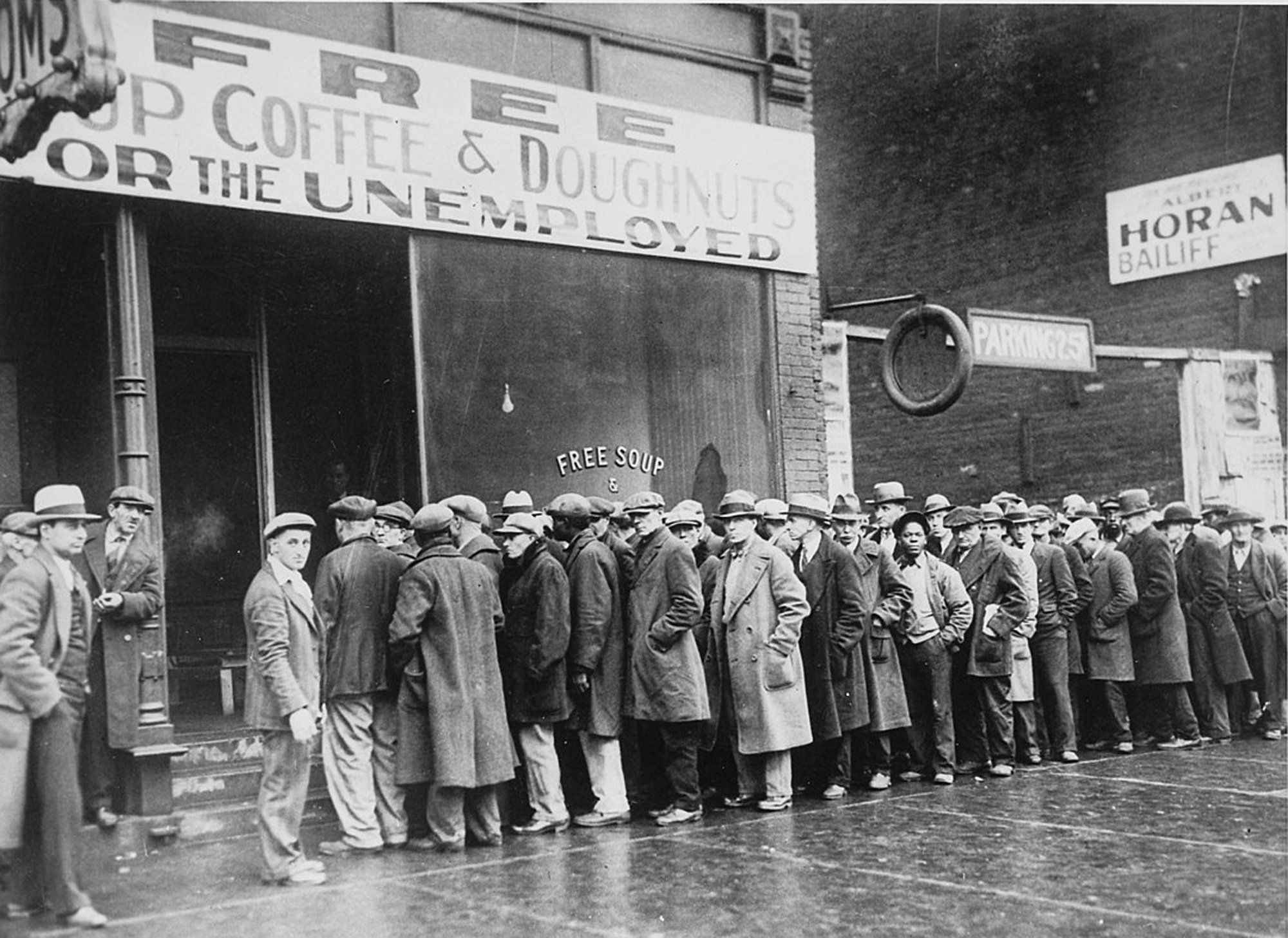

The United States entered World War I alongside the Allies in 1917, playing a crucial role in turning the tide against the Central Powers. A significant social reform arrived in 1920 with a constitutional amendment granting nationwide women’s suffrage. During the 1920s and 1930s, the advent of radio for mass communication and early television transformed nationwide communications. The Wall Street Crash of 1929 triggered the Great Depression, prompting President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal plan of “reform, recovery and relief,” a series of unprecedented and sweeping recovery programs, employment relief projects, and financial reforms and regulations.

Read more about: The United States: A Complex Legacy of Discord and Unity, Shaping a Nation’s Evolving Identity

Initially neutral during World War II, the U.S. began supplying war materiel to the Allies in March 1941 and formally entered the war in December after the Empire of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. The U.S. developed the first nuclear weapons and used them against the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, bringing the war to an end. The United States was one of the “Four Policemen”—alongside the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and China—who planned the post-war world, emerging relatively unscathed from the conflict with even greater economic power and international political influence.

The end of World War II in 1945 left the U.S. and the Soviet Union as global superpowers, each with distinct political, military, and economic spheres of influence, leading to the geopolitical tensions of the Cold War. The U.S. adopted a policy of containment to limit the USSR’s influence, engaged in regime change against perceived Moscow-aligned governments, and prevailed in the Space Race, culminating in the first crewed Moon landing in 1969. Domestically, the U.S. experienced significant economic growth, urbanization, and population expansion following World War II.

The civil rights movement gained momentum, with Martin Luther King Jr. becoming a prominent leader in the early 1960s. President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society plan led to groundbreaking and broad-reaching laws, policies, and a constitutional amendment designed to counteract the lingering effects of institutional racism. The counterculture movement brought significant social changes, including the liberalization of attitudes toward recreational drug use and sexuality. It also fostered open defiance of the military draft, leading to its end in 1973, and widespread opposition to U.S. intervention in Vietnam, resulting in a total U.S. withdrawal in 1975.

Read more about: Sophisticated GNSS Spoofing Reshapes Electronic Warfare in Middle East and Ukraine, Posing Civilian Risks

A societal shift in the roles of women significantly increased female paid labor participation during the 1970s, with the majority of American women aged 16 and older employed by 1985. The Fall of Communism and the dissolution of the Soviet Union from 1989 to 1991 marked the conclusive end of the Cold War, firmly establishing the United States as the world’s sole superpower. This cemented the United States’ global influence, reinforcing the concept of the “American Century” as the U.S. dominated international political, cultural, economic, and military affairs.

The 1990s witnessed the longest recorded economic expansion in American history, a dramatic decline in U.S. crime rates, and rapid advancements in technology. Throughout this decade, innovations such as the World Wide Web, the evolution of the Pentium microprocessor, rechargeable lithium-ion batteries, the first gene therapy trial, and cloning either emerged in the U.S. or were significantly improved upon there. The Human Genome Project formally launched in 1990, and Nasdaq became the first U.S. stock market to trade online in 1998, marking a new era of digital commerce and scientific exploration.

The Gulf War of 1991 saw an American-led international coalition successfully expel an Iraqi invasion force that had occupied neighboring Kuwait. However, the serene period of the 1990s was tragically interrupted by the September 11 attacks on the United States in 2001 by the pan-Islamist militant organization al-Qaeda, which initiated the global war on terror and subsequent military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq. The U.S. housing bubble culminated in 2007 with the Great Recession, representing the largest economic contraction since the Great Depression.

In the 2010s and early 2020s, the United States has experienced increased political polarization and democratic backsliding. This polarization was violently manifested in the January 2021 Capitol attack, when a mob of insurrectionists entered the U.S. Capitol, seeking to prevent the peaceful transfer of power in an attempted self-coup d’état, highlighting contemporary challenges to the nation’s democratic foundations.

Read more about: Understanding Womanhood: A Comprehensive Exploration of Biology, Society, and Evolving Roles

Geographically, the United States ranks as the world’s third-largest country by total area, behind Russia and Canada. The 48 contiguous states and the District of Columbia span a combined area of 3,119,885 square miles. In 2021, the U.S. accounted for 8% of the Earth’s permanent meadows and pastures and 10% of its cropland, reflecting its significant agricultural capacity. Starting in the east, the coastal plain of the Atlantic seaboard transitions into inland forests and rolling hills of the Piedmont plateau region. The Appalachian Mountains and the Adirondack Massif separate the East Coast from the Great Lakes and the vast grasslands of the Midwest.

The Mississippi River System, the world’s fourth-longest river system, flows predominantly north–south through the country’s center. To the west, the flat and fertile prairie of the Great Plains stretches onward, occasionally interrupted by a highland region in the southeast. The Rocky Mountains, west of the Great Plains, extend north to south across the country, with peaks exceeding 14,000 feet in Colorado. The Yellowstone Caldera, a supervolcano underlying Yellowstone National Park in the Rockies, stands as the continent’s largest volcanic feature. Further west lie the rocky Great Basin and the Chihuahuan, Sonoran, and Mojave deserts.

In the northwest corner of Arizona, carved by the Colorado River, lies the Grand Canyon, a steep-sided canyon and popular tourist destination renowned for its overwhelming visual size and intricate, colorful landscape. The Cascade and Sierra Nevada mountain ranges run close to the Pacific coast. Remarkably, the lowest and highest points in the contiguous United States are both located in California, approximately 84 miles apart, showcasing the state’s extreme topographical diversity. Alaska’s Denali (Mount McKinley), at an elevation of 20,310 feet, stands as the highest peak in both the country and the continent. Active volcanoes are common throughout Alaska’s Alexander and Aleutian Islands. Hawaii, located entirely outside North America, consists of volcanic islands and is physiographically and ethnologically part of the Polynesian subregion of Oceania.

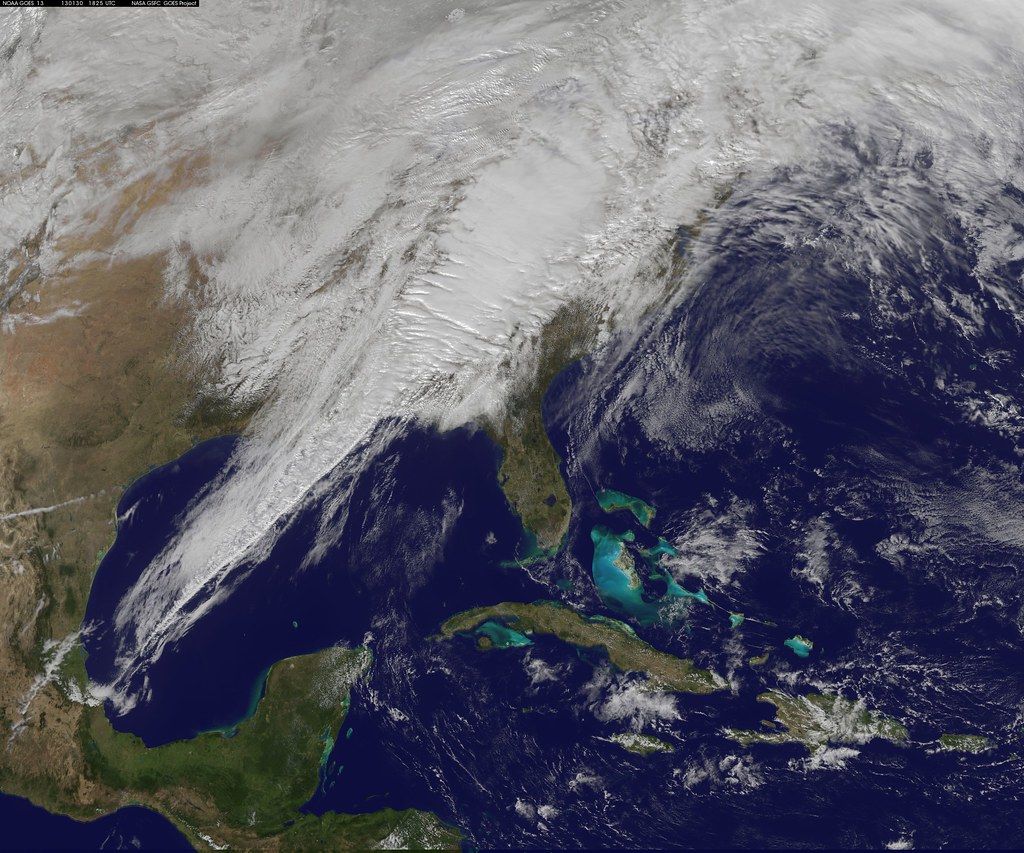

Due to its immense size and diverse geography, the United States encompasses most climate types. East of the 100th meridian, the climate varies from humid continental in the north to humid subtropical in the south. The western Great Plains are semi-arid, while many mountainous areas of the American West experience an alpine climate. The Southwest is characterized by an arid climate, coastal California by a Mediterranean climate, and coastal Oregon, Washington, and southern Alaska by an oceanic climate. Most of Alaska is subarctic or polar, while Hawaii, the southern tip of Florida, and U.S. territories in the Caribbean and Pacific enjoy tropical climates.

Read more about: Texas’s Shifting Sands of Power: Unpacking the Complex Forces Shaping the Lone Star State’s Political Destiny

The United States experiences more high-impact extreme weather incidents than any other country. States bordering the Gulf of Mexico are prone to hurricanes, and the country is home to most of the world’s tornadoes, primarily in Tornado Alley. Climate change has led to more frequent extreme weather in the U.S. in the 21st century, with three times the number of reported heat waves compared to the 1960s. Since the 1990s, droughts in the American Southwest have become more persistent and severe, with regions most attractive to the population often being the most vulnerable.

The U.S. stands as one of 17 megadiverse countries, boasting a large number of endemic species. Approximately 17,000 species of vascular plants are found in the contiguous United States and Alaska, while Hawaii alone is home to over 1,800 species of flowering plants, few of which occur on the mainland. The nation’s fauna includes 428 mammal species, 784 birds, 311 reptiles, 295 amphibians, and around 91,000 insect species, highlighting its rich ecological tapestry. The bald eagle, the national emblem since 1782, was officially declared the national bird in 2024.

The country is home to 63 national parks and hundreds of other federally managed parks, forests, and wilderness areas, administered by the National Park Service and other agencies. About 28% of the country’s land is publicly owned and federally managed, primarily in the Western States, with most of this land protected, although some is leased for commercial use and less than one percent is designated for military purposes. Environmental issues in the United States encompass debates on non-renewable resources and nuclear energy, air and water pollution, biodiversity, logging and deforestation, and climate change. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is the federal agency tasked with addressing most environmental-related issues.

The idea of wilderness has profoundly shaped the management of public lands since the 1964 Wilderness Act. The Endangered Species Act of 1973 provides a crucial framework for protecting threatened and endangered species and their habitats, implemented and enforced by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service. In 2024, the U.S. ranked 35th among 180 countries in the Environmental Performance Index, reflecting ongoing efforts and challenges in environmental stewardship.

Read more about: Inside the Boeing 777X Test Jet: Folding Wings, Giant Engines, and the Push Towards Certification

At its core, the United States is a federal republic of 50 states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. It also asserts sovereignty over five unincorporated territories and several uninhabited island possessions. It is the world’s oldest surviving federation, and its presidential system of national government has influenced many newly independent states worldwide following decolonization. The Constitution of the United States serves as the country’s supreme legal document, forming the bedrock of its governance. Most scholars characterize the United States as a liberal democracy, reflecting its commitment to individual liberties and representative rule.

The federal government, headquartered in Washington, D.C., is composed of three distinct branches: legislative, executive, and judicial. The U.S. Constitution meticulously establishes a separation of powers designed to create a system of checks and balances, preventing any single branch from gaining undue supremacy. The U.S. Congress, a bicameral legislature, comprises the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Senate consists of 100 members—two from each state—elected by their state’s voters for a six-year term. These elections are staggered, ensuring only one-third of senators are up for election every two years. The House of Representatives has 435 members, each elected for a two-year term by the constituency of the congressional district where they reside. State legislatures determine the contiguous district boundaries, ensuring each U.S. congressional district has an equivalent population and sends one representative to Congress.

Read more about: Texas’s Shifting Sands of Power: Unpacking the Complex Forces Shaping the Lone Star State’s Political Destiny

The U.S. Congress holds significant powers, including making federal law, declaring war, approving treaties, controlling the power of the purse, and possessing the power of impeachment. A foremost non-legislative function is its power to investigate and oversee the executive branch, with congressional oversight often delegated to committees and facilitated by Congress’s subpoena power. Much of Congress’s work is performed by various committees, each appointed for a specific purpose or function, and committee membership is traditionally bipartisan. The U.S. president serves as the head of state, commander-in-chief of the military, and chief executive of the federal government, also holding the ability to veto legislative bills from the U.S. Congress. This intricate system of governance reflects a carefully crafted framework intended to ensure stability and uphold democratic principles, demonstrating the enduring complexity and resilience of the American political landscape.