California, a state in the Western United States, truly stands as a testament to unparalleled diversity and enduring dynamism. Resting proudly on the Pacific Coast, it is a vast expanse, bordering Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and sharing an international boundary with the Mexican state of Baja California to the south. With nearly 40 million residents spread across an expansive area of 163,696 square miles (423,970 km²), it holds the remarkable distinction of being the largest state by population and the third-largest by sheer area.

From its bustling metropolitan areas to its serene natural landscapes, California offers a kaleidoscope of experiences. The state’s geography is incredibly varied, stretching from the rugged Pacific Coast and vibrant urban centers in the west to the majestic Sierra Nevada mountains in the east. It encompasses the lush redwood and Douglas fir forests of the northwest, contrasting sharply with the arid expanse of the Mojave Desert in the southeast.

This incredible diversity is not merely geographical; it permeates every aspect of the state, from its rich historical tapestry to its groundbreaking economic prowess. California is a place where ancient histories converge with future-shaping innovations, making its story a truly compelling narrative. Let us embark on a journey through the multifaceted wonders of this extraordinary Golden State.

The very name “California” carries a fascinating mystique, rooted in legend and early exploration. It originates from the 1510 epic Las Sergas de Esplandián, a work penned by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo. This literary creation introduced the mythical island of California and its powerful ruler, Queen Calafia, imbuing the name with a sense of adventure and wonder from its very inception.

Queen Calafia’s kingdom was vividly imagined as a remote land, incredibly rich in gold and pearls. It was said to be inhabited by beautiful dark-skinned women who lived like Amazons, donning gold armor and sharing their domain with griffins and other strange beasts. This captivating fictional narrative fueled the imaginations of early explorers, shaping their perceptions of the new lands they sought.

The Spaniards were the first to bestow the name Las Californias upon the peninsula of Baja California in modern-day Mexico. As Spanish explorers and settlers ventured further north and inland, the region known as California, or Las Californias, expanded. Eventually, it came to include lands north of the peninsula, Alta California, a portion of which would ultimately become the present-day U.S. state we know today.

Intriguingly, despite early on-the-ground explorations, the idea of California as an island, as depicted by Rodríguez, persisted on many European maps well into the 18th century. Even a 2017 state legislative document acknowledges that “Numerous theories exist as to the origin and meaning of the word ‘California’,” concluding that by 1541, the name was added to a map, “presumably by a Spanish navigator,” with its exact origin remaining a subject of enduring fascination.

Long before European colonization, California was a realm of profound cultural and linguistic richness, boasting one of the most diverse Indigenous landscapes in pre-Columbian North America. Historians widely estimate that at least 300,000 people thrived across California before the arrival of Europeans. These Indigenous peoples comprised more than 70 distinct ethnic groups, each adapting ingeniously to environments ranging from towering mountains and vast deserts to isolated islands and majestic redwood forests.

Their sophisticated understanding of their lands led to the development of complex forms of ecosystem management. Practices such as forest gardening ensured the regular availability of vital food and medicinal plants, embodying a profound commitment to sustainable agriculture. Furthermore, to mitigate the devastating impact of large wildfires, Indigenous peoples pioneered controlled burning, a practice whose immense benefits were officially recognized by the California government as recently as 2022.

Political organization among these groups was equally diverse, encompassing bands, tribes, and villages. Along the resource-rich coasts, large chiefdoms flourished, including the Chumash, Pomo, and Salinan peoples. Trade, intermarriage, the expertise of craft specialists, and strategic military alliances fostered intricate social and economic relationships among numerous groups, illustrating a sophisticated pre-colonial society.

While nations would sometimes engage in warfare, most armed conflicts were small-scale battles, often driven by a quest for vengeance rather than territorial acquisition. Societal roles were generally defined, with women typically responsible for weaving, harvesting, processing, and preparing food, while men undertook hunting and other forms of physical labor. Importantly, many societies recognized and honored individuals whom the Spanish referred to as joyas, or “men who dressed as women,” who held significant responsibilities in rituals and performed women’s social roles, often referred to as two-spirit individuals. Early Spanish settlers, however, harbored animosity towards them and actively sought their elimination.

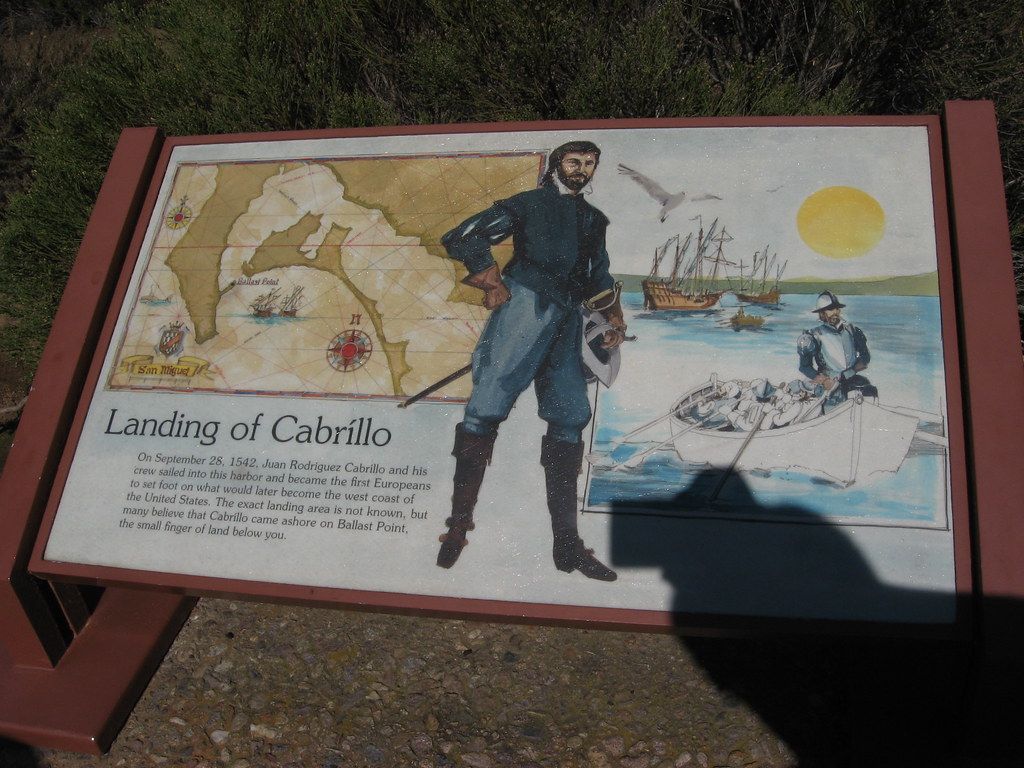

The first European contact with California’s coast occurred in 1542, when a Spanish maritime expedition led by Portuguese captain Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo explored the region. Commissioned by Antonio de Mendoza, the Viceroy of New Spain, Cabrillo’s expedition sought new trade opportunities, entering San Diego Bay on September 28, 1542, and reaching as far north as San Miguel Island.

Further claims were made in 1579 when the privateer and explorer Francis Drake explored and asserted English rights over an undefined portion of the California coast, landing north of what would become San Francisco. A notable historical moment occurred in 1587 when Filipino sailors, arriving on Spanish ships at Morro Bay, became the first Asians to set foot on what would later become the United States. Sebastián Vizcaíno subsequently mapped the California coast in 1602 for New Spain, making landfall in Monterey.

A truly pivotal event in the Spanish colonization of California was the Portolá expedition of 1769–70. This endeavor resulted in the establishment of numerous missions, presidios, and pueblos, laying the groundwork for permanent European presence. Gaspar de Portolá led the military and civil contingent overland from Sonora, while Junípero Serra guided the religious component by sea from Baja California.

In 1769, Portolá and Serra jointly established Mission San Diego de Alcalá and the Presidio of San Diego, marking the Spanish Empire’s first religious and military settlements in California. By 1770, their expedition culminated in the founding of the Presidio of Monterey and Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo on Monterey Bay. Following this, Father-President Serra continued to establish 21 Spanish missions along El Camino Real and the California coast, many of which became the nuclei for major California cities, including San Francisco, San Diego, Ventura, and Santa Barbara.

Another significant expedition, led by Juan Bautista de Anza in 1775–76, ventured deeper into California’s interior and northern reaches. Anza’s journey identified numerous sites for future missions, presidios, and pueblos, which subsequent settlers would establish. Gabriel Moraga, a member of this expedition, famously christened many of California’s prominent rivers, including the Sacramento River and the San Joaquin River, in 1775–1776. His son, José Joaquín Moraga, would go on to found the pueblo of San Jose in 1777, establishing California’s first civilian-settled city.

Concurrently, sailors from the Russian Empire explored California’s northern coast, establishing a trading post and small fortification at Fort Ross in 1812. This outpost primarily supplied Russia’s Alaskan colonies with food. However, Fort Ross ultimately proved unsuccessful in attracting settlers or sustaining long-term trade, leading to its abandonment by 1841. During the War of Mexican Independence, Alta California remained largely unaffected, though many Californios supported independence, believing Spain had neglected the region and stifled its growth. With Mexican independence, California ports gained the freedom to trade with foreign merchants, ushering in a new era of commerce.

In 1821, the Mexican War of Independence successfully liberated the Mexican Empire, including California, from Spanish rule. For the next quarter-century, Alta California existed as a remote, sparsely populated administrative district of the newly independent country of Mexico, which soon transformed into a republic. A pivotal shift occurred by 1834 when the missions, which had controlled much of the state’s prime land, were secularized and became the property of the Mexican government.

This period saw the governor granting vast square leagues of land to politically influential individuals, leading to the rise of enormous ranchos, or cattle ranches, as the dominant institutions of Mexican California. These ranchos thrived under the ownership of Californios, Hispanic natives of California, who engaged in a lucrative trade of cowhides and tallow with Boston merchants. Beef, however, did not emerge as a significant commodity until the transformative California Gold Rush of 1849.

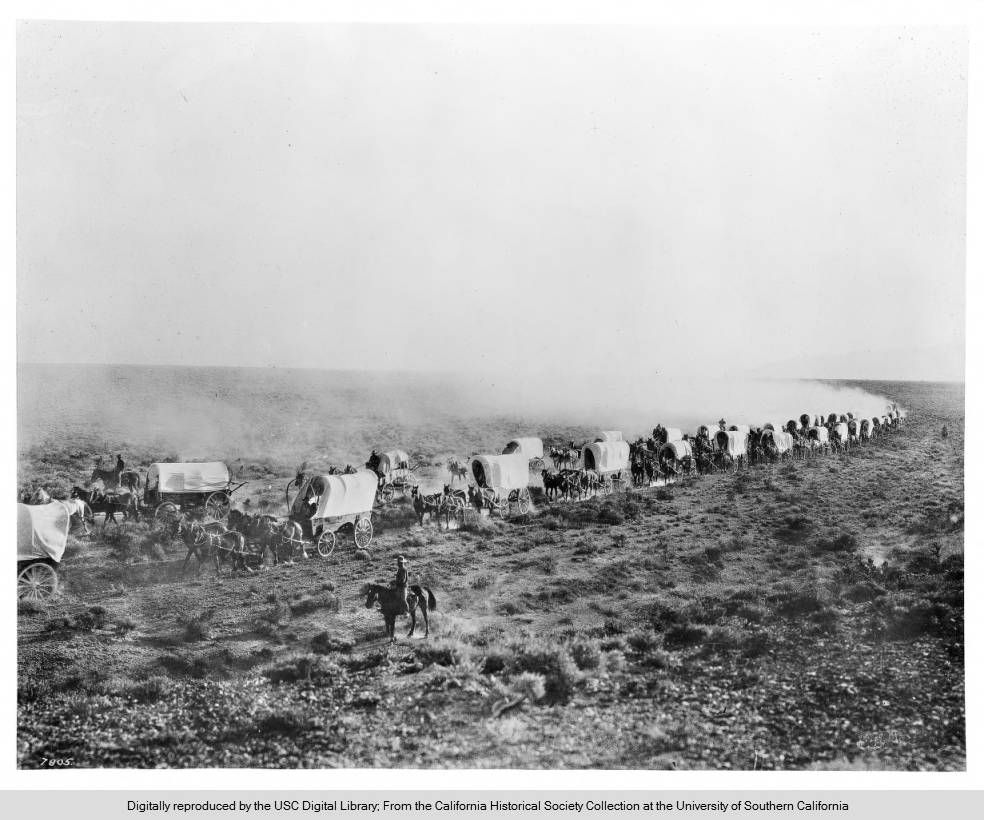

From the 1820s onward, trappers and settlers from the United States and Canada began arriving in Northern California, utilizing trails like the Siskiyou, California, Oregon, and Old Spanish Trails to traverse the rugged mountains and harsh deserts. The early government of independent Mexico proved highly unstable, and this volatility was reflected in California, which experienced a series of internal and external armed disputes from 1831 onwards. Amidst this tumultuous political landscape, Juan Bautista Alvarado secured the governorship from 1836 to 1842.

The military action that initially propelled Alvarado to power had briefly declared California an independent state, and it had been aided by Anglo-American residents, including Isaac Graham. However, in 1840, the arrest of one hundred of these residents who lacked passports ignited the Graham Affair, a diplomatic incident partially resolved through the intervention of Royal Navy officials. One of California’s largest ranchers, John Marsh, played a crucial role in paving the way for American acquisition. After failing to obtain justice against squatters in Mexican courts, he became convinced that California should become part of the United States.

Marsh launched an influential letter-writing campaign, extolling California’s climate, fertile soil, and other reasons to settle there, while also detailing the best routes, which became known as “Marsh’s route.” His widely circulated letters, reprinted in newspapers across the country, sparked the first wagon trains heading to California. He later intervened in a military conflict between the Mexican general Manuel Micheltorena and the California governor he had replaced, Juan Bautista Alvarado, at the Battle of Providencia near Los Angeles. Marsh successfully convinced both sides to cease fighting, leading to Micheltorena’s defeat and the return of California-born Pio Pico to the governorship, a series of events that ultimately facilitated California’s annexation by the United States.

The year 1846 marked a pivotal moment with the Bear Flag Revolt, where American settlers in and around Sonoma rebelled against Mexican rule. They proudly raised the Bear Flag, featuring a bear, a star, a red stripe, and the words “California Republic,” symbolizing their declaration of independence. William B. Ide served as the Republic’s sole president, playing a central role in this revolt. This uprising by American settlers served as a direct prelude to the American military invasion of California, coordinated closely with nearby American military commanders.

The California Republic, however, was short-lived, as the same year saw the outbreak of the Mexican–American War, which lasted from 1846 to 1848. Commodore John D. Sloat of the United States Navy initiated the U.S. military invasion of California in 1846 by sailing into Monterey Bay. Northern California quickly capitulated to the United States forces within less than a month. Despite this, Californios in Southern California mounted a spirited resistance against American forces, engaging in notable military battles such as San Pasqual and Dominguez Rancho in the south, and Olómpali and Santa Clara in the north. After a series of defensive engagements in the south, the Treaty of Cahuenga was signed by the Californios on January 13, 1847, effectively securing de facto American control in California.

Following the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on February 2, 1848, which formally ended the Mexican–American War, the westernmost portion of the annexed Mexican territory of Alta California rapidly became the American state of California. The remaining parts of the old territory were subsequently divided into the new American Territories of Arizona, Nevada, Colorado, and Utah. The more lightly populated and arid lower region of old Baja California remained under Mexican sovereignty. In 1846, the total settler population of western Alta California was estimated at no more than 8,000, alongside about 100,000 Native Americans, a significant decline from approximately 300,000 before Hispanic settlement in 1769.

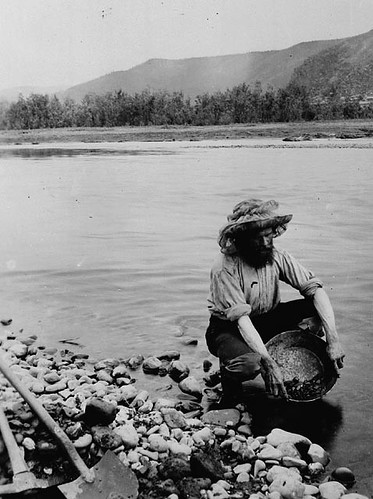

Just one week before the official American annexation of the area in 1848, a momentous discovery of gold forever altered California’s demographics and finances. A massive influx of immigration ensued, as prospectors and miners arrived by the thousands, transforming the region. The population swelled with United States citizens, Europeans, Middle Easterners, Chinese, and other immigrants during the great California gold rush. By the time California applied for statehood in 1850, its settler population had skyrocketed to 100,000, and by 1854, over 300,000 settlers had arrived. San Francisco, in particular, witnessed an astonishing population increase from 500 to 150,000 between 1847 and 1870.

The seat of government under Spanish and Mexican rule had been Monterey from 1777 until 1845, though Pio Pico, the last Mexican governor of Alta California, briefly moved the capital to Los Angeles in 1845. The United States consulate was also located in Monterey. In 1849, the state’s first Constitutional Convention was held in Monterey, where one of its initial tasks was to decide on a location for the new state capital. The first full legislative sessions took place in San Jose from 1850 to 1851.

Subsequent capital locations included Vallejo (1852–1853) and nearby Benicia (1853–1854), though these proved inadequate. Sacramento has proudly served as the capital since 1854, with only a brief interruption in 1862 when legislative sessions were temporarily moved to San Francisco due to severe flooding in Sacramento. Once its state constitution was finalized, California applied to the U.S. Congress for admission to statehood. On September 9, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850, California was admitted as a free state, with September 9 now recognized as a state holiday.

During the American Civil War from 1861 to 1865, California played a crucial role by sending vital gold shipments eastward to Washington, bolstering the Union cause. Despite a significant contingent of pro-South sympathizers within the state, California managed to contribute to the Union war effort, albeit not with full military regiments sent eastward. Nevertheless, several smaller military units within the Union army, such as the “California 100 Company,” were unofficially associated with the state due to a majority of their members hailing from California.

At the time of California’s admission into the Union, travel between California and the rest of the continental United States was a prolonged and perilous undertaking. However, this changed dramatically just nineteen years later, and seven years after President Lincoln’s approval, with the completion of the first transcontinental railroad in 1869. This monumental achievement slashed travel time from the eastern states to California to a mere week, revolutionizing connectivity.

The state’s fertile lands proved exceptionally well-suited for fruit cultivation and agriculture in general. Vast expanses were dedicated to growing wheat, other cereal crops, various vegetables, cotton, and an abundance of nut and fruit trees, including oranges in Southern California. This laid a robust foundation for the state’s prodigious agricultural output, especially in the Central Valley and other highly productive regions.

In the nineteenth century, a substantial number of migrants from China journeyed to California, drawn by the allure of the Gold Rush or the promise of work. While Chinese laborers proved indispensable in constructing the transcontinental railroad from California to Utah, perceived job competition ignited anti-Chinese riots across the state. This intense pressure from California ultimately contributed to the passage of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which curtailed migration from China.

Amidst California’s rapid growth in the American period, a tragic and devastating chapter unfolded, now known as the California genocide. Between 1846 and 1873, U.S. government agents and private settlers perpetrated numerous massacres against Indigenous Californians. Estimates suggest at least 9,456 Indigenous people were killed, with some figures reaching as high as 100,000 deaths.

Under earlier Spanish and Mexican rule, California’s original native population had already experienced a precipitous decline, primarily due to Eurasian diseases against which Indigenous peoples had no natural immunity. The advent of American administration brought further devastation, as California’s first governor, Peter Hardeman Burnett, instituted policies that have been described as a state-sanctioned policy of elimination of California’s indigenous people. In his Second Annual Message to the Legislature in 1851, Burnett chillingly announced, “That a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the races until the Indian race becomes extinct must be expected. While we cannot anticipate the result with but painful regret, the inevitable destiny of the race is beyond the power and wisdom of man to avert.

As was the case in other American states, Indigenous peoples were forcibly removed from their ancestral lands by American settlers, including miners, ranchers, and farmers. Despite California’s admission to the American union as a free state, the “loitering or orphaned Indians” were de facto enslaved by their new Anglo-American masters under the 1850 Act for the Government and Protection of Indians. Shockingly, one of these de facto slave auctions, approved by the Los Angeles City Council, persisted for nearly two decades. Many massacres occurred, with hundreds of Indigenous people killed by settlers driven by land greed.

Between 1850 and 1860, the California state government allocated approximately 1.5 million dollars, with about 250,000 of that sum reimbursed by the federal government, to hire militias. While ostensibly purposed for protecting settlers, these militias were responsible for perpetrating numerous massacres of Indigenous people. Additionally, Indigenous communities were forcibly relocated to reservations and rancherias, often small, isolated, and lacking adequate natural resources or government funding to sustain the populations living on them. This settler colonialism proved to be a profound calamity for Indigenous peoples. Several scholars and Native American activists, including Benjamin Madley and Ed Castillo, have unequivocally described the actions of the California government as a genocide, a view echoed by California’s 40th governor, Gavin Newsom. Benjamin Madley estimates that between 1846 and 1873, between 9,492 and 16,092 Indigenous people were killed, including between 1,680 and 3,741 by the U.S. Army.

The 20th century witnessed California’s continued transformation and emergence as a global leader. Thousands of Japanese people migrated to the state, though this was unfortunately met with discriminatory policies such as the 1913 Alien Land Act, which barred Asian immigrants from owning land. During World War II, Japanese Americans in California faced the injustice of internment in concentration camps, an act for which California formally apologized in 2020.

Migration to California dramatically accelerated in the early 20th century, particularly with the completion of transcontinental highways like the iconic Route 66. From 1900 to 1965, the state’s population soared from fewer than one million to become the largest in the Union. By 1940, the Census Bureau reported California’s population as 6% Hispanic, 2.4% Asian, and 90% non-Hispanic white, reflecting the ongoing shifts in its demographic landscape.

To meet the escalating needs of its burgeoning population, California undertook extraordinary engineering feats. Marvels like the California and Los Angeles Aqueducts, the Oroville and Shasta Dams, and the iconic Bay and Golden Gate Bridges were constructed, demonstrating the state’s ambitious vision and engineering prowess. In a visionary move to develop an efficient public education system, the state government adopted the California Master Plan for Higher Education in 1960.

The early 20th century also saw Hollywood studios, such as Paramount Pictures, transforming the area into the world capital of film, solidifying Los Angeles’s status as a global economic hub. Attracted by the mild Mediterranean climate, affordable land, and the state’s diverse geography, filmmakers established the studio system in Hollywood in the 1920s, profoundly influencing global entertainment for decades.

California played a crucial role during World War II, manufacturing 9% of U.S. armaments, ranking third nationally behind New York and Michigan. The state excelled in military ship production, easily ranking first with drydock facilities in San Diego, Los Angeles, and the San Francisco Bay Area. The war effort offered immense hiring opportunities, leading to a population boom from immigration drawn by work in its war factories, military bases, and training facilities.

Following World War II, California’s economy continued its expansion, propelled by robust aerospace and defense industries, though their size would later decrease after the Cold War. A significant turning point occurred when Stanford University began actively encouraging its faculty and graduates to remain in the state and develop a high-tech region, which blossomed into the world-renowned Silicon Valley. As a result, California has become a global center for the entertainment and music industries, technology, engineering, the aerospace industry, and stands as the undeniable U.S. center of agricultural production. Just before the Dot Com Bust, California boasted the fifth-largest economy in the world, a testament to its economic dynamism.

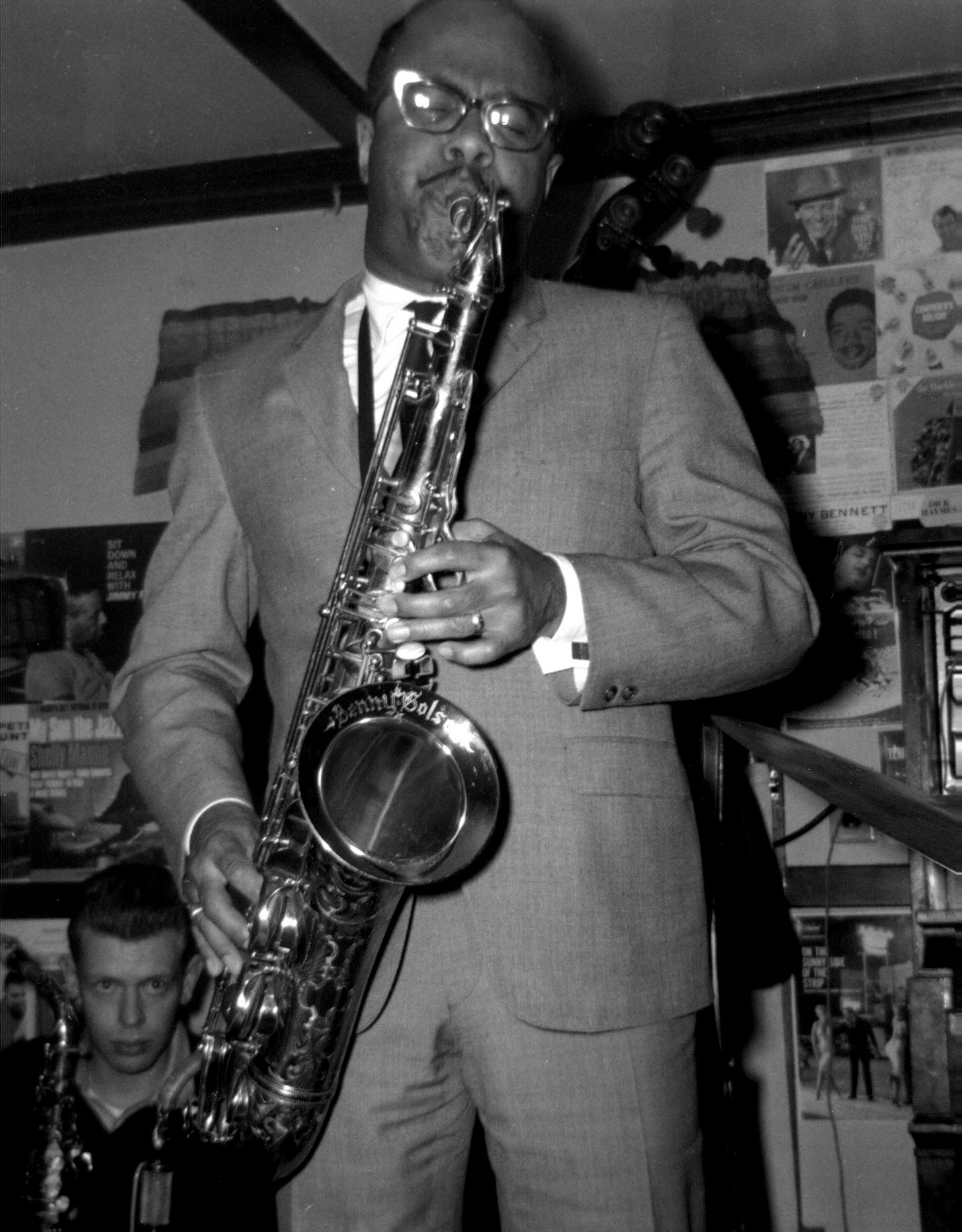

The mid and late twentieth century also saw significant race-related incidents and social movements. Tensions between police and African Americans, compounded by unemployment and poverty in inner cities, culminated in events like the 1992 Rodney King riots. California became the vibrant hub of the Black Panther Party, known for empowering African Americans to defend against racial injustice. Furthermore, Mexican, Filipino, and other migrant farmworkers rallied around civil rights activist Cesar Chavez in the 1960s and 70s, fighting passionately for better pay and working conditions.

California’s recent history has also been shaped by significant natural disasters, serving as stark reminders of its geological realities. The 1906 San Francisco earthquake and the 1928 St. Francis Dam flood remain among the deadliest in U.S. history. While air pollution has seen significant reductions, particularly with the substantial abatement of brown haze known as “smog” due to federal and state restrictions on automobile exhaust, health problems associated with pollution continue to be an ongoing concern.

An energy crisis in 2001 led to widespread rolling blackouts, soaring power rates, and the necessity of importing electricity from neighboring states, bringing heavy criticism upon Southern California Edison and Pacific Gas and Electric Company. The housing market also presented significant challenges; a modest home costing $25,000 in the 1960s could command half a million dollars or more in urban areas by 2005. Speculators, confident in ever-rising prices, bought houses to make quick profits, with compliant mortgage companies fueling the bubble, which dramatically burst in 2007–08, causing prices to crash, hundreds of billions in property values to vanish, foreclosures to soar, and financial institutions to suffer immense losses.

Despite these challenges, California remains at the forefront of innovation. The 2007 launch of the iPhone by Apple founder Steve Jobs in Silicon Valley, the world’s largest tech hub, exemplifies California’s continuing pioneering spirit. In the 21st century, the state has grappled with persistent droughts and frequent wildfires, largely attributed to climate change. From 2011 to 2017, the state endured its worst recorded drought in history, and the 2018 wildfire season was particularly devastating, marked as the state’s deadliest and most destructive. Simultaneously, atmospheric rivers are becoming increasingly prevalent, leading to intense flooding events, especially during the winter months.

California also played a crucial role in the national response to the COVID-19 pandemic, with one of the first confirmed cases in the United States occurring in the state on January 26, 2020. A state of emergency was declared on March 4, 2020, and remained in effect until Governor Gavin Newsom ended it in February 2023. A mandatory statewide stay-at-home order was issued on March 19, 2020, and was subsequently ended in January 2021.

Amidst these modern challenges, cultural and language revitalization efforts among Indigenous Californians have seen significant progress among tribes as of 2022, signaling a renewed commitment to heritage. Encouragingly, some land has begun to be returned to Indigenous stewardship, representing a vital step towards justice and reconciliation. A landmark announcement in 2022 detailed the largest dam removal and river restoration project in U.S. history for the Klamath River, hailed as a significant win for California tribes, highlighting the state’s ongoing evolution and commitment to its diverse heritage.

Covering an impressive area of 163,696 square miles (423,970 km2), California stands as the third-largest state in the United States by area, surpassed only by Alaska and Texas. It is truly one of the most geographically diverse states in the Union, often conceptually divided into two distinct regions: Southern California, encompassing its ten southernmost counties, and Northern California, comprising the 48 northernmost counties.

At the very heart of the state lies the California Central Valley, an incredibly fertile agricultural area that dominates the state’s center. This vital region is bounded by the majestic Sierra Nevada mountains to the east, the coastal mountain ranges to the west, the Cascade Range to the north, and the Tehachapi Mountains in the south. The Central Valley is divided into two by the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta.

The northern portion, known as the Sacramento Valley, serves as the watershed of the Sacramento River, while the southern portion, the San Joaquin Valley, is the watershed for the San Joaquin River. Both valleys proudly bear the names of the rivers that flow through them, sustaining their immense agricultural productivity. Through dredging, the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers have remained deep enough to allow several inland cities to function as seaports, further highlighting the state’s unique waterways.

The Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta is a critical hub for the state’s water supply, a lifeline that sustains its vast population and agricultural endeavors. Water is skillfully diverted from the delta through an extensive network of pumps and canals that traverse nearly the entire length of the state, serving the Central Valley, the State Water Projects, and numerous other essential needs. This vital water supply provides drinking water for nearly 23 million people, accounting for almost two-thirds of the state’s population, and also irrigates farms on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley.

Suisun Bay lies at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers, with its waters draining through the Carquinez Strait into San Pablo Bay, which is a northern extension of San Francisco Bay. This intricate system then connects to the vast Pacific Ocean via the iconic Golden Gate strait, showcasing a magnificent hydrological network. Off the Southern coast lie the picturesque Channel Islands, while the rugged Farallon Islands are situated west of San Francisco, adding to California’s coastal allure.

The Sierra Nevada, meaning “snowy range” in Spanish, is a breathtaking mountain range that includes Mount Whitney, the highest peak in the contiguous 48 states, towering at an impressive 14,505 feet (4,421 m). This majestic range embraces the legendary Yosemite Valley, famed for its glacially carved domes, and the awe-inspiring Sequoia National Park, home to the giant sequoia trees, which stand as the largest living organisms on Earth. It also cradles the deep freshwater Lake Tahoe, the largest lake in the state by volume.

To the east of the Sierra Nevada are the pristine Owens Valley and Mono Lake, an essential habitat for migratory birds. In the western part of the state, Clear Lake holds the distinction of being the largest freshwater lake by area entirely within California, as the larger Lake Tahoe is bisected by the California/Nevada border. The Sierra Nevada experiences Arctic temperatures in winter and hosts several dozen small glaciers, including Palisade Glacier, the southernmost glacier in the United States, adding to its rugged beauty.

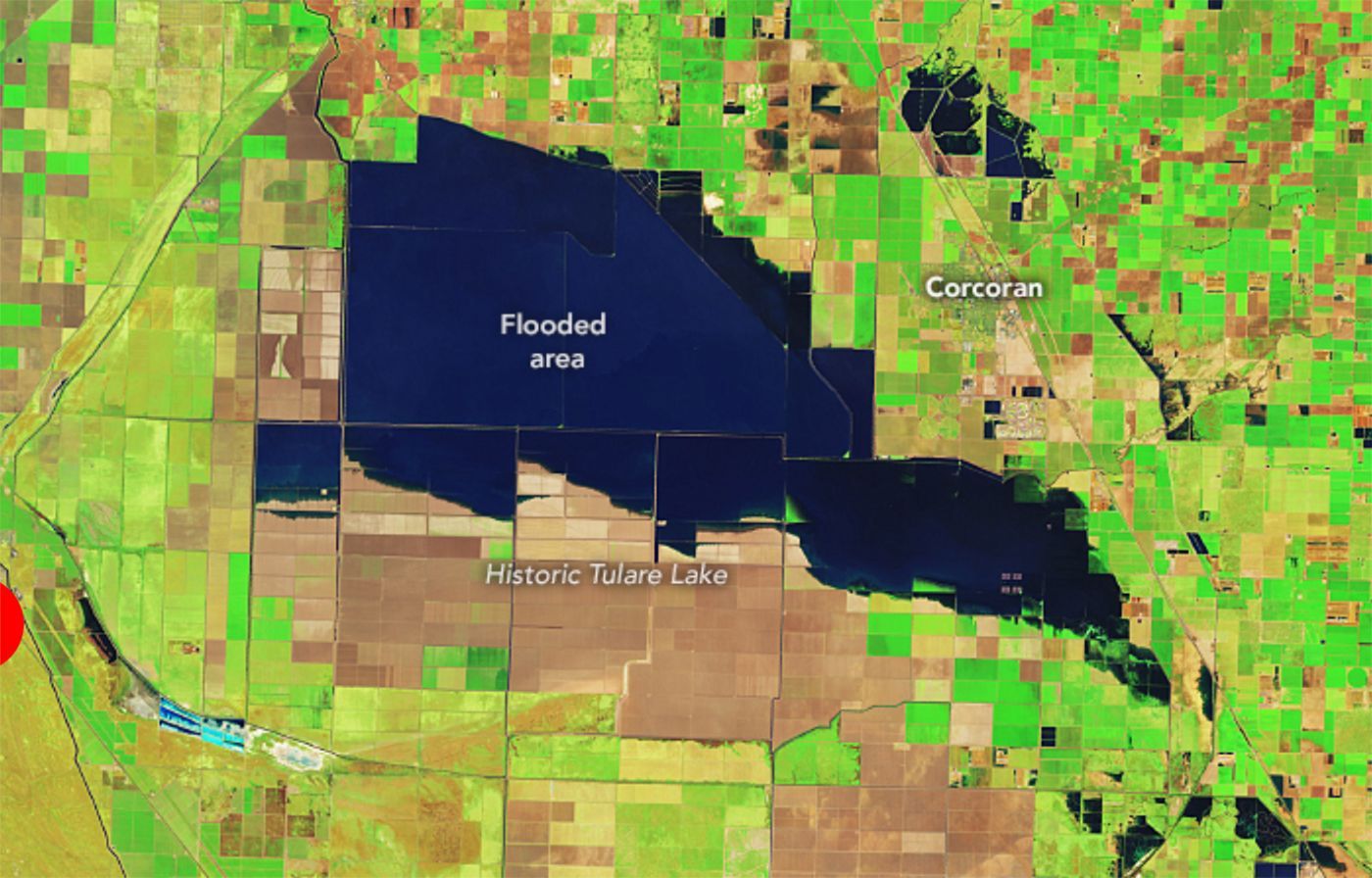

Historically, the Tulare Lake was the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi River, a remnant of the Pleistocene-era Lake Corcoran. However, it dried up by the early 20th century as its tributary rivers were diverted for agricultural irrigation and municipal water uses. Approximately 45 percent of the state’s total surface area is covered by forests, a testament to its vast natural beauty, and California boasts a diversity of pine species unmatched by any other state. In fact, California contains more forestland than any other state except Alaska, offering immense natural wealth. Many of the trees in the California White Mountains are among the oldest in the world; an individual bristlecone pine, for instance, is astonishingly over 5,000 years old.

In the south of California lies a large inland salt lake, the Salton Sea, a unique geographical feature. The south-central desert region is named the Mojave, a landscape of stark beauty and extreme conditions. To the northeast of the Mojave lies Death Valley, which holds the distinction of containing the lowest and hottest place in North America, the Badwater Basin, at a striking −279 feet (−85 m). Remarkably, the horizontal distance from the bottom of Death Valley to the summit of Mount Whitney is less than 90 miles (140 km), showcasing the dramatic elevation changes within the state. Indeed, almost all of southeastern California is characterized by arid, hot desert, experiencing routine extreme high temperatures during the summer months. The southeastern border of California with Arizona is entirely defined by the mighty Colorado River, a crucial source from which the southern part of the state draws about half of its water.

A majority of California’s vibrant cities are concentrated in several major metropolitan areas. In Northern California, these include the bustling San Francisco Bay Area and the Sacramento metropolitan area. In Southern California, the expansive Los Angeles area, the Inland Empire, and the San Diego metropolitan area serve as significant urban hubs. The Los Angeles Area, the Bay Area, and the San Diego metropolitan area are among the several major metropolitan areas that grace the California coast, defining its urban landscape.

As part of the dynamic Ring of Fire, California is inherently subject to a range of natural phenomena, including tsunamis, floods, droughts, the fierce Santa Ana winds, destructive wildfires, and landslides on its steep terrains. The state also encompasses several volcanoes, adding to its geological complexity. California experiences numerous earthquakes due to several major faults crisscrossing the state, with the colossal San Andreas Fault being the largest. Approximately 37,000 earthquakes are recorded each year, though most are too small to be felt. Disturbingly, among Americans at risk of serious harm from a major earthquake, two-thirds reside in California, underscoring the state’s unique geological vulnerability.

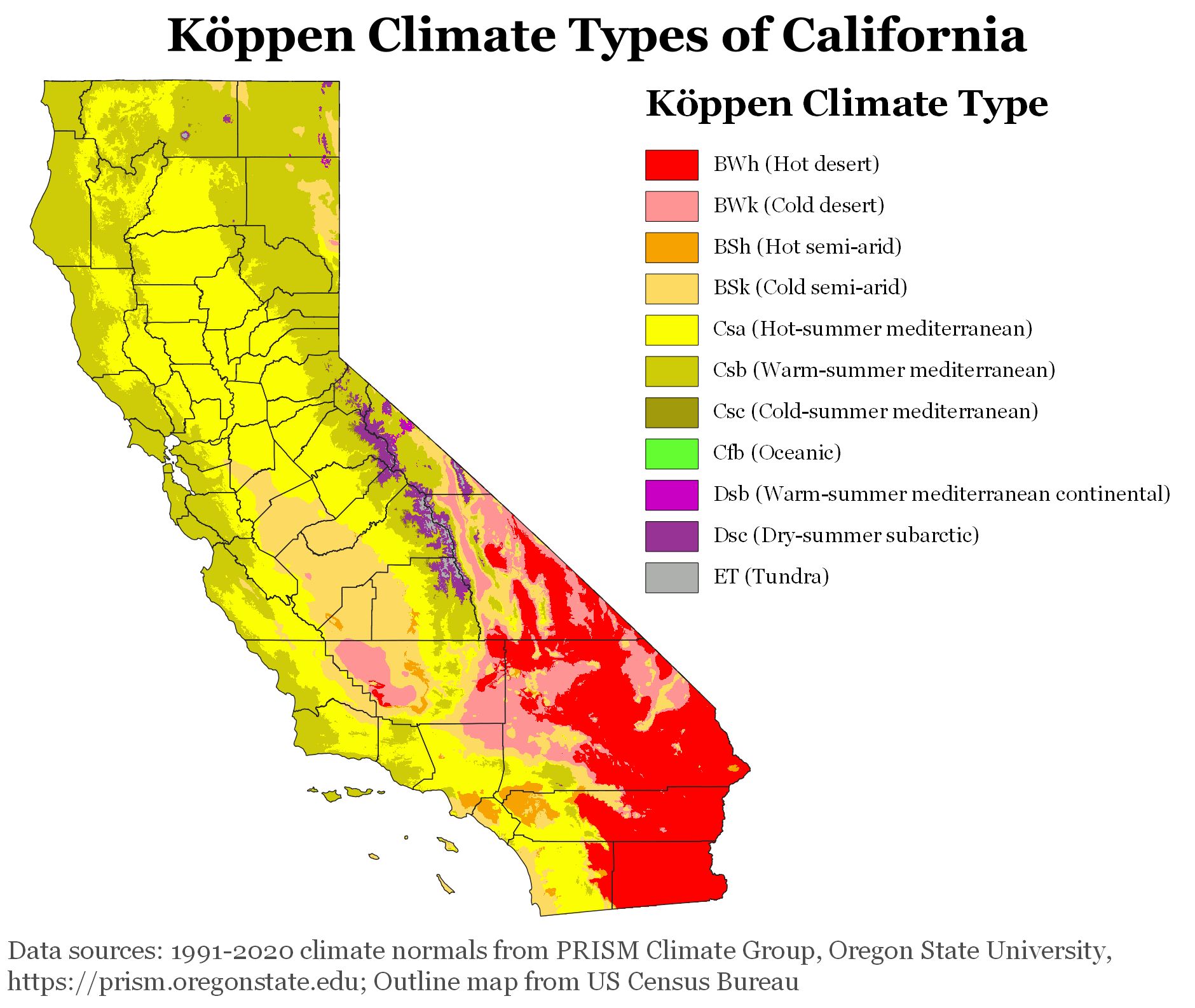

Most of California enjoys a beautiful Mediterranean climate, characterized by warm, dry summers and mild, wet winters. A distinctive feature of its coastal climate is the cool California Current offshore, which frequently creates the iconic summer fog that gracefully rolls in near the coast. This unique climate variation, combined with its diverse geography, contributes to the state’s rich biodiversity and its remarkable appeal.

California is not just a place of stunning landscapes and profound history; it is a continuously unfolding story of ambition, resilience, and global impact. From the mythical tales that gave it its name to the seismic shifts that shape its land, and from the earliest Indigenous stewardship to its current role as a world leader in technology, entertainment, and agriculture, California embodies a dynamic spirit.

It is a state that has faced immense challenges—from historical injustices to environmental extremes and economic upheavals—yet it consistently adapts, innovates, and rebuilds. California’s enduring allure lies in its vibrant blend of cultures, its relentless pursuit of progress, and its breathtaking natural beauty. It stands as a powerful testament to what is possible when human ingenuity meets a landscape of such grand, untamed potential, continuing to captivate and inspire the world with its ever-evolving narrative.

The Golden State truly represents a living, breathing testament to continuous transformation, a place where past lessons inform future aspirations, and where the spirit of innovation burns ever brightly. It remains a beacon of progress, a hub of creativity, and a land of boundless opportunity, inviting us all to witness its remarkable, unfolding journey. California’s story is one of enduring grandeur, a saga that continues to be written with each passing day.