Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia, is a South American nation with insular regions extending into North America. It uniquely boasts coastlines along both the Caribbean Sea to the north and the Pacific Ocean to the west, making it the only South American country with this distinction. The mainland shares borders with Venezuela, Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, and Panama, reinforcing its central position on the continent. The country covers an area of 1,141,748 square kilometers (440,831 sq mi) and sustains a population of around 52 million people.

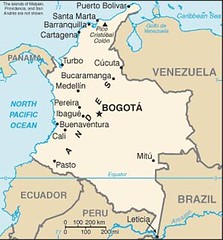

Bogotá, the Capital District, serves as Colombia’s largest city and its main financial and cultural hub. Other significant urban areas include Medellín, Cali, Barranquilla, and Cartagena. The name ‘Colombia’ itself is derived from the Italian navigator Christopher Columbus, initially conceived as a reference to the entire New World. It was later adopted by the Republic of Colombia in 1819, formed from the expansive territories of the old Viceroyalty of New Granada.

The nation’s name evolved through several forms, including ‘Republic of New Granada,’ ‘Granadine Confederation,’ and ‘United States of Colombia,’ before finally settling on its current designation, the ‘Republic of Colombia,’ in 1886. Colombia’s rich cultural heritage reflects its history as a colony, beautifully fusing cultural elements brought by immigration from Europe and the Middle East with those from the African diaspora, as well as with traditions of the various Indigenous civilizations that predate colonization. Spanish is the official language, although Creole, English, and 64 other languages are recognized regionally, highlighting its profound linguistic diversity.

Colombia is widely recognized for its healthcare system, which is considered “the best healthcare in Latin America according to the World Health Organization and 22nd in the world.” Its diversified economy stands as the third-largest in South America, bolstered by macroeconomic stability and favorable long-term growth prospects. As one of the world’s seventeen megadiverse countries, Colombia uniquely possesses “the highest level of biodiversity per square mile in the world and the second-highest level overall,” encompassing the Amazon rainforest, highlands, grasslands, and deserts.

This extraordinary ecological variety contributes significantly to its global importance. The nation is a key member of major global and regional organizations, including the UN, the WTO, the OECD, the OAS, the Pacific Alliance, and the Andean Community, showcasing its commitment to international cooperation. Furthermore, Colombia holds the distinction of being a NATO Global Partner and a major non-NATO ally of the United States, underscoring its robust strategic alliances and diplomatic standing on the world stage.

Colombia’s present territory served as a crucial corridor for early human civilization, facilitating movement from Mesoamerica and the Caribbean to the Andes and Amazon basin. The oldest archaeological finds, dating from the Paleoindian period (18,000–8000 BCE), are from the Pubenza and El Totumo sites in the Magdalena Valley. The oldest pottery discovered in the Americas, found in San Jacinto, dates remarkably to 5000–4000 BCE, indicating advanced ancient cultures. Indigenous people inhabited the territory that is now Colombia by at least 12,500 BCE, with nomadic hunter-gatherer tribes trading near Bogotá.

Between 5000 and 1000 BCE, these hunter-gatherer tribes transitioned to agrarian societies, leading to the establishment of fixed settlements and the appearance of pottery. Beginning in the 1st millennium BCE, Amerindian groups including the Muisca, Zenú, Quimbaya, and Tairona developed sophisticated political systems called cacicazgos, characterized by a pyramidal structure of power headed by caciques. The Muisca, inhabiting the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, notably formed a confederation, farming maize, potato, quinoa, and cotton, and trading gold, emeralds, and especially rock salt.

Spanish exploration in the region commenced in 1499 with Alonso de Ojeda reaching the Guajira Peninsula, followed by Rodrigo de Bastidas exploring the Caribbean coast in 1500. Vasco Núñez de Balboa founded Santa María la Antigua del Darién in 1510, recognized as the first stable European settlement on the continent. Strategic coastal cities such as Santa Marta (founded in 1525) and Cartagena (founded in 1533) were subsequently established, serving as vital points for colonial expansion.

Spanish conquistador Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada led a pivotal expedition to the interior in April 1536, christening the districts he encountered “New Kingdom of Granada” and provisionally founding its capital, Santa Fe de Bogotá, in August 1538. Other significant expeditions included Sebastián de Belalcázar’s founding of Cali (1536) and Popayán (1537), and German conquistador Nikolaus Federmann’s crossing of the Llanos Orientales in search of the mythical city of gold, El Dorado, which greatly lured Europeans to the region. Conquistadors frequently forged alliances with the enemies of different indigenous communities, a strategy crucial to their conquest and the creation and maintenance of the empire.

Indigenous peoples in Colombia experienced a severe decline in population due to conquest and the devastating impact of Eurasian diseases like smallpox, to which they had no immunity. Regarding the land as seemingly deserted, the Spanish Crown facilitated the sale of properties to interested persons, leading to the establishment of large farms and the possession of mines. Nautical science in Spain achieved great development in the 16th century, forming an essential pillar of the Iberian expansion. In 1542, the region of New Granada, along with other Spanish possessions in South America, became part of the vast Viceroyalty of Peru.

By 1547, New Granada attained the status of a separate captaincy-general within the viceroyalty, with Santa Fe de Bogota as its capital, indicating its growing strategic importance. The Royal Audiencia was created in 1549, and New Granada was governed by the Royal Audience of Santa Fe de Bogotá, which oversaw various provinces, though ultimate decisions were still made by the Council of the Indies in Spain. European slave traders began bringing enslaved Africans to the Americas in the 16th century, facilitated by Spain’s ‘asiento system,’ which licensed merchants from other nations to supply slaves, as Spain did not establish factories in Africa. Notably, indigenous peoples were legally protected as subjects of the Spanish Crown and therefore could not be enslaved.

To protect the indigenous peoples, Spanish colonial authorities established various forms of land ownership and regulation, including ‘resguardos’ and ‘encomiendas.’ However, secret anti-Spanish discontent was already brewing due to Spain’s prohibition of direct trade between the Viceroyalty of Peru (including Colombia) and the Viceroyalty of New Spain (including the Philippines), which limited access to sought-after Asian products like silk and porcelain. This fostered illegal trade networks, with smuggled Asian goods ending up in Córdoba, Colombia, as a distribution center, due to collusion against Spanish authorities.

The Viceroyalty of New Granada was officially re-established in 1739, with Santa Fé de Bogotá as its capital, and it included provinces corresponding mainly to today’s Venezuela, Ecuador, and Panama. Bogotá consequently became one of the principal administrative centers of Spanish possessions in the New World. In 1739, Great Britain declared war on Spain, targeting Cartagena, but a massive British expeditionary force was crippled by devastating outbreaks of disease and forced to withdraw, a decisive Spanish victory that secured their Caribbean dominance until the Seven Years’ War. The 18th-century Royal Botanical Expedition to New Granada (started 1783), led by José Celestino Mutis, meticulously classified plants and wildlife, and established the first astronomical observatory in Santa Fe de Bogotá, fostering intellectual growth among figures who would later play pivotal roles in the independence movement, such as Francisco José de Caldas and Alexander von Humboldt.

Rebellions against Spanish rule had occurred throughout the colonial period, but the movement seeking outright independence from Spain sprang up around 1810, culminating in the Colombian Declaration of Independence issued on 20 July 1810, now celebrated as the nation’s Independence Day. This pivotal movement drew inspiration from Saint-Domingue’s independence (present-day Haiti) in 1804, and was spearheaded by influential figures like the Venezuelan-born Simón Bolívar and Francisco de Paula Santander, along with Antonio Nariño, who opposed Spanish centralism. Cartagena notably declared its independence in November 1811, setting an early precedent for self-governance, and in 1811, the United Provinces of New Granada were proclaimed.

However, the emergence of two distinct ideological currents among the patriots—federalism and centralism—gave rise to a period of instability known as the ‘Patria Boba.’ Shortly after the Napoleonic Wars, Ferdinand VII, restored to the Spanish throne, attempted to retake northern South America with military forces, restoring the viceroyalty under Juan de Sámano. This retribution fueled renewed rebellion, which, combined with a weakened Spain, enabled a successful rebellion led by Simón Bolívar, who finally proclaimed independence in 1819. The pro-Spanish resistance was ultimately defeated in the present territory of Colombia by 1822 and in Venezuela by 1823, though the Independence War resulted in a devastating loss of between 250,000 and 400,000 lives, representing 12–20% of the pre-war population.

The territory of the former Viceroyalty of New Granada subsequently became the Republic of Colombia, organized as a grand union that initially encompassed the current territories of Colombia, Panama, Ecuador, and Venezuela, along with parts of Guyana and Brazil. The Congress of Cúcuta in 1821 adopted a constitution for this new Republic, with Simón Bolívar becoming its first President and Francisco de Paula Santander its Vice President. However, the new republic proved unstable, and the grand project of Gran Colombia ultimately collapsed in 1830, leading to the formation of modern Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela as independent states. Colombia holds the distinction of being the first constitutional government in South America.

The Liberal and Conservative parties, founded in 1848 and 1849, respectively, stand as two of the oldest surviving political parties in the Americas, marking an early development of robust political institutions. A significant social reform was achieved with the abolition of slavery in the country in 1851. Internal political and territorial divisions persisted, leading to the “Department of Cundinamarca” adopting the name “New Granada,” which it kept until 1858 when it became the “Confederación Granadina.” Following a two-year civil war, the “United States of Colombia” was created in 1863, before finally becoming the “Republic of Colombia” in 1886. These internal divisions between bipartisan political forces frequently ignited very bloody civil wars, the most significant being the Thousand Days’ War (1899–1902), in which between 100,000 and 180,000 Colombians lost their lives.

The United States’ intentions to influence the area, particularly concerning the Panama Canal construction and control, directly led to the secession of the Department of Panama in 1903 and its political independence. To redress President Roosevelt’s role in the creation of Panama, the United States paid Colombia $25,000,000 in 1921, seven years after the canal’s completion, and Colombia recognized Panama under the terms of the Thomson–Urrutia Treaty. A territory dispute with Peru far in the Amazon basin escalated into war, which was eventually resolved by a League of Nations peace deal in 1934 that awarded the disputed area to Colombia. Soon after, Colombia achieved some degree of political stability, which was tragically interrupted by a bloody conflict spanning the late 1940s and early 1950s, a period famously known as ‘La Violencia’ (‘The Violence’), primarily stemming from mounting tensions between the two leading political parties.

The assassination of the Liberal presidential candidate Jorge Eliécer Gaitán on 9 April 1948 ignited the ensuing riots in Bogotá, known as El Bogotazo, which rapidly spread throughout the country and claimed the lives of at least 180,000 Colombians. Colombia notably entered the Korean War when Laureano Gómez was elected president, becoming the only Latin American country to join the war in a direct military role as an ally of the United States, with the resistance of Colombian troops at Old Baldy being particularly important. The violence between the two political parties eventually decreased, first under Gustavo Rojas, who deposed the President in a coup d’état and negotiated with the guerrillas, and then under the military junta of General Gabriel París. Following Rojas’ deposition, the Colombian Conservative Party and the Colombian Liberal Party agreed to create the National Front, a coalition that jointly governed the country for 16 years, with the presidency alternating every four years and parity in other offices, effectively ending ‘La Violencia’ and attempting far-reaching social and economic reforms in cooperation with the Alliance for Progress.

Despite progress in certain sectors, many social and political problems persisted, leading to the formal creation of leftist guerrilla groups such as the FARC, the ELN, and the M-19 to fight the government and political apparatus. Since the 1960s, the country has suffered from an asymmetric low-intensity armed conflict between government forces, leftist guerrilla groups, and right-wing paramilitaries, both of which escalated in the 1990s, mainly in remote rural areas. Throughout the armed conflict, human rights defenders have fought for the respect of human rights, despite staggering opposition. Several guerrilla organizations decided to demobilize after peace negotiations between 1989 and 1994, signaling a desire for resolution. The United States has been heavily involved in the conflict since its beginnings, encouraging the Colombian military to attack leftist militias in the early 1960s as part of its fight against communism, while international actors like mercenaries and multinational corporations such as Chiquita Brands International also contributed to the violence.

Beginning in the mid-1970s, Colombian drug cartels became major producers, processors, and exporters of illegal drugs, primarily marijuana and cocaine, adding a complex layer to the national challenges. On 4 July 1991, a new Constitution was promulgated, and the changes generated by this new constitution were largely viewed as positive by Colombian society, aiming for modernization and reform. The administration of President Álvaro Uribe (2002–2010) adopted the democratic security policy, which included an integrated counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency campaign, and concurrently, the government’s economic plan promoted confidence in investors. As part of a controversial peace process, the AUC (right-wing paramilitaries) formally ceased to function as an organization, marking a complex step towards de-escalation.

In February 2008, millions of Colombians demonstrated against FARC and other outlawed groups, expressing a collective desire for peace. After extensive peace negotiations in Cuba, the Colombian government of President Juan Manuel Santos and the FARC-EP guerrillas announced a final agreement to end the conflict; however, a referendum to ratify the deal was unsuccessful. Afterward, the Colombian government and the FARC signed a revised peace deal in November 2016, which the Colombian congress approved, leading to President Santos being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2016 for his tireless efforts towards peace. The Government subsequently began a comprehensive process of attention and reparation for victims of the conflict.

HRW stated that Colombia shows modest progress in the struggle to defend human rights, highlighting ongoing challenges. A Special Jurisdiction of Peace has been created to investigate, clarify, prosecute, and punish serious human rights violations and grave breaches of international humanitarian law which occurred during the armed conflict, aiming to satisfy victims’ right to justice, and Pope Francis paid tribute to the victims of the conflict during his visit to Colombia. In June 2018, Iván Duque, the candidate of the right-wing Democratic Center party, won the presidential election, and he was sworn in as the new President of Colombia on 7 August 2018, succeeding Juan Manuel Santos.

Colombia’s relations with neighboring Venezuela have fluctuated significantly due to ideological differences between the two governments, with Colombia offering humanitarian support in the form of food and medicines to mitigate supply shortages in Venezuela. The Colombian Foreign Ministry maintained that all efforts to resolve Venezuela’s crisis should be peaceful. Colombia also proposed the idea of the Sustainable Development Goals, which culminated in a final document adopted by the United Nations, demonstrating its commitment to international cooperation. In February 2019, Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro cut off diplomatic relations with Colombia after Colombian President Iván Duque had helped Venezuelan opposition politicians deliver humanitarian aid to their country, leading Colombia to recognize Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guaidó as the country’s legitimate president, and in January 2020, Colombia rejected Maduro’s proposal to restore diplomatic relations. Protests started on 28 April 2021 when the government proposed a tax bill that would greatly expand the range of the 19 percent value-added tax. The 19 June 2022 election run-off vote concluded with a historic win for former guerrilla Gustavo Petro, who garnered 50.47% of the vote compared to 47.27% for independent candidate Rodolfo Hernández. President Iván Duque was constitutionally prevented from seeking re-election due to the country’s single-term limit for the presidency. On 7 August 2022, Gustavo Petro was sworn in, becoming the country’s first leftist president, marking a significant historical shift, with Francia Marquez making history as the first black person elected as vice president.

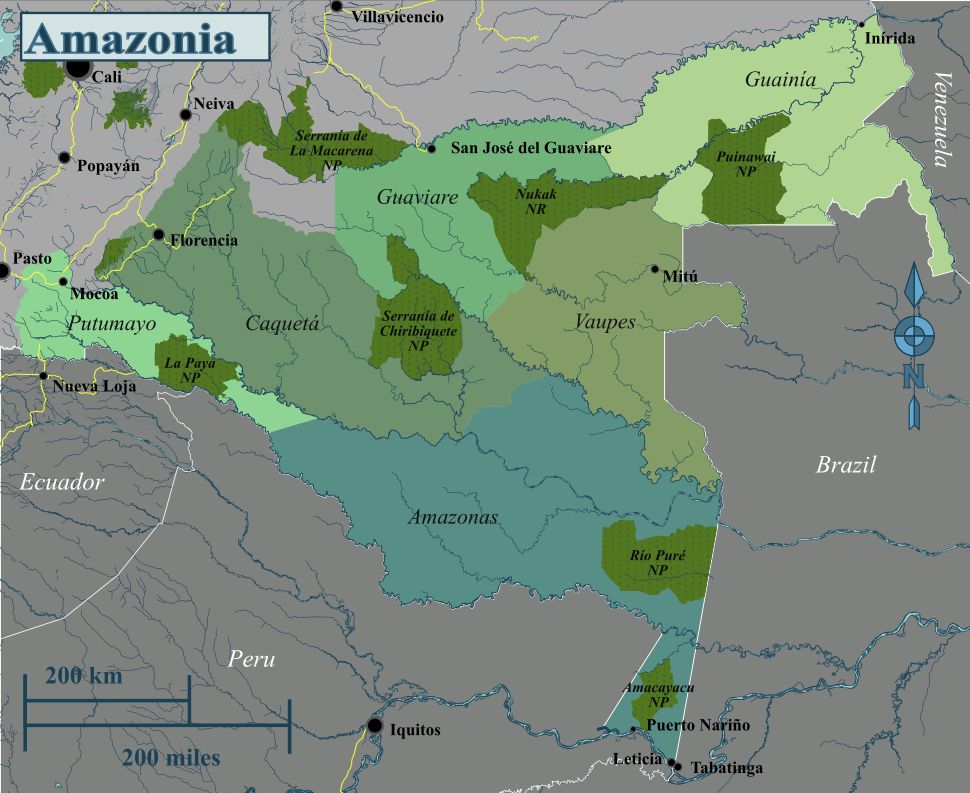

The geography of Colombia is characterized by its six main natural regions, including the Andes mountain range region, the Pacific Coastal region, the Caribbean coastal region, the Llanos (plains), the Amazon rainforest region, and the insular area comprising islands in both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The country notably lies between latitudes 12°N and 4°S and between longitudes 67° and 79°W. East of the Andes, the savanna of the Llanos and the jungle of the Amazon rainforest together make up over half of Colombia’s territory, yet they contain less than 6% of the population, indicating vast, sparsely inhabited regions. The Caribbean coast, home to 21.9% of the population, features low-lying plains and major port cities like Barranquilla and Cartagena, but it also contains the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountain range, which includes the country’s tallest peaks (Pico Cristóbal Colón and Pico Simón Bolívar), and the La Guajira Desert.

In the interior of Colombia, the Andes are the prevailing geographical feature, part of the Ring of Fire, a region of the world subject to earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. Most of Colombia’s population centers are located in these interior highlands. Beyond the Colombian Massif (in the southwestern departments of Cauca and Nariño), these are divided into three branches known as cordilleras: the Cordillera Occidental (including the city of Cali), the Cordillera Central (including Medellín, Manizales), and the Cordillera Oriental (including Bogotá, Bucaramanga). Peaks in the Cordillera Occidental exceed 4,700 m (15,420 ft), and in the Cordillera Central and Cordillera Oriental, they reach 5,000 m (16,404 ft). Bogotá, at 2,600 m (8,530 ft), holds the distinction of being the highest city of its size in the world. The main rivers of Colombia, such as the Magdalena and Cauca, feed into four main drainage systems: the Pacific drain, the Caribbean drain, the Orinoco Basin, and the Amazon Basin.

Colombia’s climate is tropical but presents significant variations within its six natural regions, depending on altitude, temperature, humidity, winds, and rainfall. This results in a diverse range of climate zones, including tropical rainforests, savannas, steppes, deserts, and mountain climates, where the climate is primarily determined by elevation. The warm altitudinal zone (below 1,000 meters or 3,281 ft), where temperatures are above 24 °C (75.2 °F), covers about 82.5% of the country’s total area. The temperate climate altitudinal zone (between 1,001 and 2,000 meters or 3,284 and 6,562 ft) is characterized by an average temperature ranging between 17 and 24 °C (62.6 and 75.2 °F). The cold climate is present between 2,001 and 3,000 meters (6,565 and 9,843 ft), with temperatures varying between 12 and 17 °C (53.6 and 62.6 °F). Beyond these lie the alpine conditions of the forested zone, the treeless grasslands of the páramos, and above 4,000 meters (13,123 ft), where temperatures are below freezing, the glacial zone of permanent snow and ice.

Colombia is notably one of the megadiverse countries in biodiversity, ranking first in bird species with over 1,900, which is more than in Europe and North America combined. It possesses the highest level of biodiversity per square mile in the world and the second-highest level overall, only surpassed by Brazil, which is approximately seven times larger. About 10% of the Earth’s species live in Colombia, including 10% of the world’s mammals, 14% of amphibian species, and 18% of bird species. The national flower, the endemic orchid Cattleya trianae, is named for the Colombian botanist José Jerónimo Triana. As for plants, the country hosts between 40,000 and 45,000 plant species, equivalent to 10% or 20% of the total global species.

Furthermore, Colombia is the second most diverse country in freshwater fish, with about 2,000 species of marine fish. It boasts the most endemic species of butterflies, is first in orchid species, and has approximately 7,000 species of beetles. It ranks second in the number of amphibian species and third in reptiles and palms, with an estimated 1,900 species of mollusks and about 300,000 species of invertebrates. Colombia encompasses 32 terrestrial biomes and 314 types of ecosystems. Protected areas and the “National Park System” cover an area of about 14,268,224 hectares (142,682.24 km2), accounting for 12.77% of the Colombian territory, reflecting significant conservation efforts. Compared to neighboring countries, rates of deforestation in Colombia are still relatively low. Colombia had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 8.26/10, ranking it 25th globally out of 172 countries. Moreover, Colombia is the sixth country in the world by magnitude of total renewable freshwater supply, and still has large reserves of freshwater, underscoring its vast natural resources.

The government of Colombia operates within the framework of a presidential participatory democratic republic, as established in the Constitution of 1991. In accordance with the principle of separation of powers, government is divided into three branches: the executive branch, the legislative branch, and the judicial branch. As the head of the executive branch, the President of Colombia serves as both head of state and head of government, elected by popular vote to a single four-year term, with a 2015 repeal of a prior constitutional amendment that changed the one-term limit. The legislative branch is represented nationally by the bicameral Congress, comprising a 166-seat Chamber of Representatives elected in electoral districts and a 102-seat Senate elected nationally, with members serving four-year terms.

The judicial branch is headed by four high courts: the Supreme Court (penal and civil matters), the Council of State (administrative law and executive legal advice), the Constitutional Court (assuring constitutional integrity), and the Superior Council of Judicature (auditing the judicial branch). Colombia operates a system of civil law, which since 1991 has been applied through an adversarial system. Former President Álvaro Uribe’s democratic security policy remained popular among Colombians, with his approval rating peaking at 76% in 2009. Juan Manuel Santos won the presidency in 2010 and re-election in 2014, leading key peace negotiations with the FARC.

In 2018, Iván Duque won the presidential election, serving a four-year term beginning August 7, 2018. In a historic shift, Gustavo Petro won the 2022 election run-off, becoming Colombia’s first leftist president, sworn in on August 7, 2022, with Francia Marquez becoming the first black vice president. Colombia’s foreign relations with Venezuela have fluctuated due to ideological differences, leading to a diplomatic cut-off in 2019 after Colombian President Ivan Duque aided Venezuelan opposition politicians in delivering humanitarian aid, with Colombia recognizing Juan Guaidó as Venezuela’s legitimate president. Protests in 2021 over a tax bill reflected ongoing societal dynamics, underscoring the nation’s continuous engagement with its evolving political landscape. Colombia is a key member of major global and regional organizations, including the UN, WTO, OECD, OAS, Pacific Alliance, and Andean Community; it is also a NATO Global Partner and a major non-NATO ally of the United States, showcasing its robust international standing and commitment to global affairs.

From the ancient echoes of its pre-Columbian inhabitants to the complexities of its modern democratic republic, Colombia’s narrative is one of profound transformation and enduring resilience. It is a nation continually shaped by powerful historical forces, marked by both periods of profound struggle and extraordinary progress. The unparalleled richness of its natural world, from majestic cordilleras to vast rainforests, serves not just as geographical markers but as symbols of an unmatched ecological wealth that mirrors the deep spirit and vibrant cultural tapestry of its people. Colombia’s journey through self-determination has been one of continuous evolution, a testament to its collective strength and adaptive capacity.

Its unwavering commitment to peace, evidenced by the arduous peace processes and the establishment of a Special Jurisdiction of Peace to ensure victims’ justice, alongside its robust economic stability and globally recognized healthcare system, reflects a profound dedication to its citizens and their future well-being. Colombia consistently redefines itself, embracing its rich heritage while forging a dynamic path forward in a rapidly changing world. Its active role in the international community, dedication to democratic governance, and remarkable cultural fusion paint a compelling portrait of a nation poised for continued growth and influence on the world stage, embodying a truly unique South American narrative shaped by the interplay of historical depth, natural splendor, and the enduring spirit of its people.