Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci, a name synonymous with genius, stands as a towering figure of the High Renaissance. Born in 1452, he was a true Italian polymath, excelling across an astonishing array of disciplines—from painting and draughtsmanship to engineering, science, theory, sculpture, and architecture. His fame, initially rooted in his artistic prowess, has only expanded over centuries to encompass the full breadth of his intellectual curiosity and groundbreaking contributions, making him a perpetual source of fascination and admiration.

Indeed, Leonardo epitomized the Renaissance humanist ideal, embodying a pursuit of knowledge and mastery across all aspects of human endeavor. His profound impact on subsequent generations of artists and thinkers is a testament to his unparalleled vision and relentless spirit of inquiry. To this day, few figures in history command such widespread recognition and inspire as much scholarly and popular interest as da Vinci.

Join us as we embark on an in-depth journey through the foundational periods and pivotal achievements that shaped this extraordinary individual. In this first part of our exploration, we’ll peel back the layers of myth and marvel at the formative experiences, intellectual breakthroughs, and artistic triumphs that defined Leonardo’s early career, setting the stage for his indelible mark on Western civilization, and forever cementing his place as a true visionary.

1. **Leonardo, The Quintessential Renaissance Polymath**When we speak of Leonardo da Vinci, we are truly speaking of the quintessential Renaissance polymath, a term that barely scratches the surface of his immense talents. Active from 1452 to 1519, he seamlessly moved between the roles of painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect, demonstrating an almost limitless capacity for innovation and understanding. It’s this breathtaking versatility that solidified his image as the embodiment of the Renaissance humanist ideal, a person whose intellectual curiosity knew no bounds and whose artistic and scientific pursuits were deeply interconnected.

His legacy, therefore, is not confined to a single field but rather spans an entire spectrum of human knowledge and creativity. While his paintings garnered him initial acclaim, his notebooks reveal a mind constantly at work, exploring, documenting, and conceptualizing ideas far ahead of his time. The collective works and theories he developed comprise a contribution to later generations of artists matched only by that of his younger contemporary, Michelangelo.

This broad engagement with the world, seeking to understand its every intricate detail, is what makes Leonardo so compelling. He didn’t just practice art or science; he integrated them, viewing the human body as a machine, the landscape as a dynamic system, and the act of creation as a blend of observation, analysis, and imaginative synthesis. His life was a testament to the belief that all knowledge is interconnected, and that true genius lies in the ability to see those connections and apply them across diverse domains.

Read more about: Beyond the Brushstrokes: 14 Defining Principles of Leonardo da Vinci’s Revolutionary Life and Enduring Genius

2. **The Revolutionary Power of His Notebooks**Beyond his breathtaking artistic output, Leonardo’s notebooks represent perhaps the most profound testament to his intellectual curiosity and empirical thinking. These thousands of pages are a veritable treasure trove, filled with intricate drawings and meticulous notes on an astonishing variety of subjects. From the delicate structures of human anatomy to the vastness of astronomy, the subtle details of botany, the precision of cartography, the nuances of painting, and even the ancient records of palaeontology, no subject seemed too mundane or too grand for his inquisitive mind.

What makes these notebooks particularly revolutionary is their sheer scope and depth, offering an unparalleled glimpse into the mind of a genius at work. They functioned as his personal laboratory, sketchbook, and philosophical treatise all rolled into one. Here, he recorded observations, sketched inventions, and theorized about everything from the flight of birds to the flow of water, often accompanied by detailed illustrations that stand as masterpieces in their own right. This practice of exhaustive documentation was itself a pioneering approach to scientific inquiry.

Despite their incredible value, Leonardo did not publish his findings, and consequently, his substantial discoveries in areas like anatomy, civil engineering, hydrodynamics, geology, optics, and tribology had little to no direct influence on subsequent science during his lifetime. Nevertheless, these notebooks have incited continuous interest and admiration since his death, revealing a scientific mind that was centuries ahead of its time. They remain a constant source of wonder, allowing us to reconstruct his thought processes and appreciate the depth of his empirical approach.

Read more about: Decoding Da Vinci: A People Magazine Journey Through the Life and Legacy of the Renaissance’s Ultimate Genius

3. **Formative Years: Apprenticeship with Andrea del Verrocchio**Leonardo’s journey into the world of art and science began in the mid-1460s when his family relocated to Florence, then a vibrant hub of Christian Humanist thought and culture. Around the tender age of 14, he entered the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio, who was widely regarded as the leading Florentine painter and sculptor of his era, as a ‘garzone’ or studio boy. This apprenticeship was a pivotal period, laying the groundwork for the vast array of skills that would define his later career.

By the age of 17, Leonardo had formally become an apprentice, a role he maintained for seven transformative years. During this time, he was immersed in both theoretical training and an extensive range of technical skills crucial to a successful artist’s repertoire. This included drafting, chemistry, metallurgy, metal working, plaster casting, and even leather working, mechanics, and woodwork, alongside the more traditional artistic skills of drawing, painting, sculpting, and modelling. This comprehensive education exposed him to the holistic nature of art production in the Renaissance, far beyond mere brushwork.

One of the most notable collaborations from this period was on Verrocchio’s painting, ‘The Baptism of Christ’ (c. 1472–1475). According to Vasari, Leonardo contributed the young angel holding Jesus’s robe, executing it with such superior skill that Verrocchio reportedly put down his brush, never to paint again—a claim likely apocryphal but indicative of Leonardo’s burgeoning talent. The use of the then-new technique of oil paint in areas like the landscape and Jesus’s figure also points to Leonardo’s hand, signaling his early embrace of innovative methods. He may have also served as a model for Verrocchio’s bronze ‘David’ and the archangel Raphael in ‘Tobias and the Angel,’ further embedding him in the artistic fabric of Florence.

Read more about: A Journey Through Genius: Unveiling the Life, Art, and Enduring Legacy of Leonardo da Vinci

4. **First Florentine Period: Early Commissions and Artistic Independence**By 1472, at the youthful age of 20, Leonardo had already qualified as a master in the prestigious Guild of Saint Luke, the guild encompassing artists and doctors of medicine. Remarkably, even after his father established him in his own workshop, his strong attachment to Verrocchio meant he continued to collaborate and reside with his former master. This period marked his transition from apprentice to an independent artist, a time of both continued learning and growing self-expression.

His earliest known dated work, a 1473 pen-and-ink drawing of the Arno valley, showcases his precocious talent for landscape and keen observational skills. It was also during this time that he received his first independent commission in January 1478: an altarpiece for the Chapel of Saint Bernard in the Florentine town hall, the Palazzo della Signoria. This commission was a clear indication of his increasing independence from Verrocchio’s studio, marking him as a rising star in Florence.

An anonymous early biographer, known as Anonimo Gaddiano, suggests that by 1480, Leonardo was living with the influential Medici family, often working in the garden of the Piazza San Marco. This put him in proximity to a Neoplatonic academy of artists, poets, and philosophers organized by the Medici, connecting him with leading humanist thinkers like Marsiglio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola. In March 1481, he received another significant commission, ‘The Adoration of the Magi,’ from the monks of San Donato in Scopeto. Neither of these initial independent commissions were completed, however, as Leonardo soon moved on to offer his services to Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan, marking the end of this foundational Florentine period.

Read more about: Decoding Da Vinci: A People Magazine Journey Through the Life and Legacy of the Renaissance’s Ultimate Genius

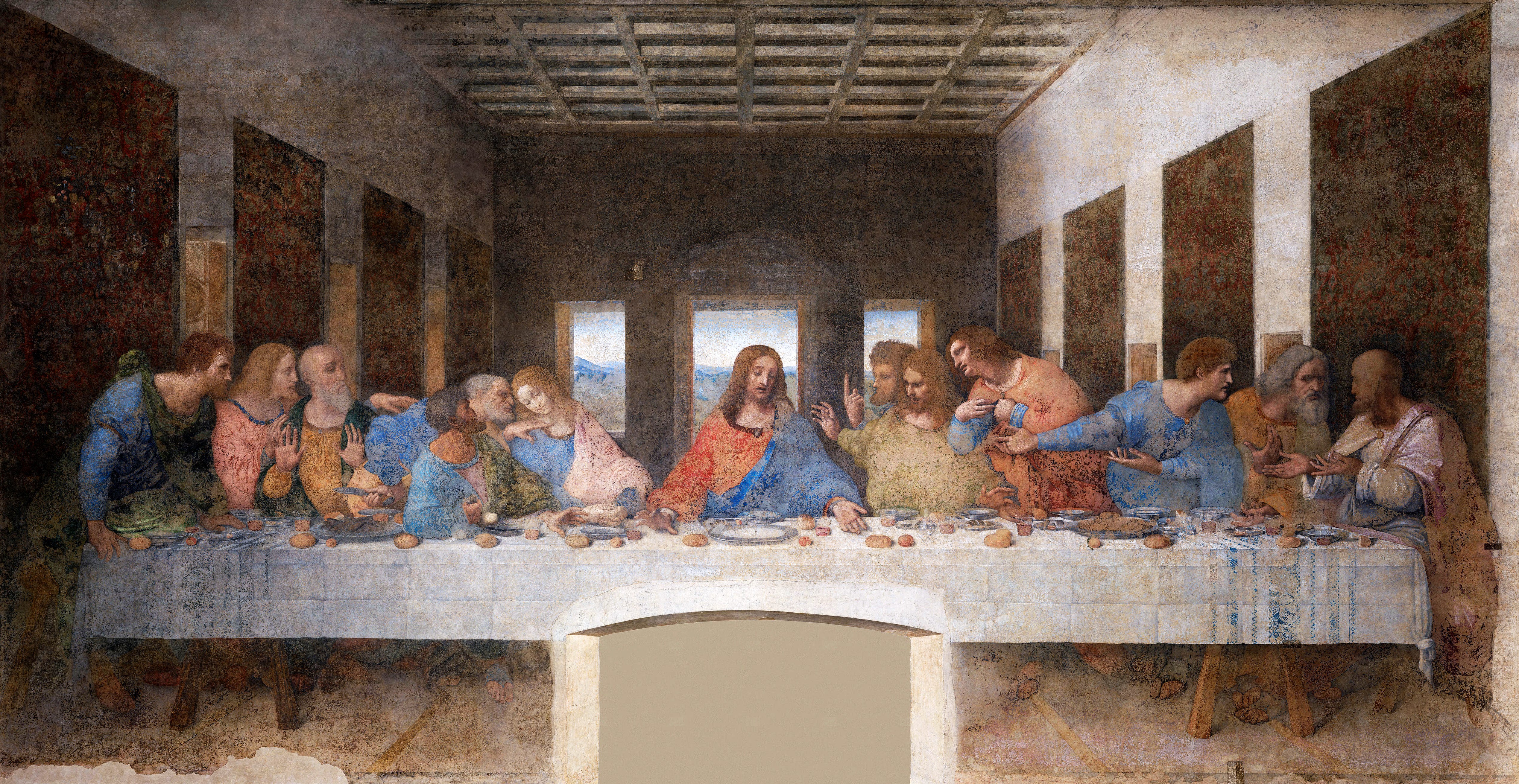

5. **The First Milanese Period: Art and Engineering for Ludovico Sforza**Leonardo’s departure for Milan in 1482 ushered in a prolific new chapter in his life, where he served Ludovico Sforza until 1499. This period saw him blend his artistic genius with his burgeoning engineering and scientific interests, offering a range of diverse talents outlined in his famous letter to the Duke. Among his most significant artistic commissions during this time were the iconic ‘Virgin of the Rocks’ for the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception and the monumental ‘The Last Supper’ for the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie, both demonstrating his evolving style and compositional mastery.

Beyond these celebrated paintings, Leonardo’s skills were highly sought after in other capacities. He traveled to Hungary on behalf of Sforza in 1485 to meet King Matthias Corvinus, for whom he was commissioned to paint a Madonna. He also served as a consultant in 1490 for the building site of the cathedral of Pavia, where he was captivated by the equestrian statue of Regisole, leaving behind a revealing sketch. His multidisciplinary expertise made him an invaluable asset to the Milanese court.

Sforza further engaged Leonardo on numerous grand projects, including the preparation of elaborate floats and pageants for special occasions. He also submitted a drawing and a wooden model for a competition to design the cupola for Milan Cathedral, showcasing his architectural ambitions. Perhaps most famously, he undertook the creation of a massive equestrian monument to Ludovico’s predecessor, Francesco Sforza, known as the ‘Gran Cavallo.’ This would have surpassed in size Donatello’s ‘Gattamelata’ and Verrocchio’s ‘Bartolomeo Colleoni,’ but sadly, the metal intended for its casting was diverted for cannon to defend Milan, leaving the project unfinished. Near the end of this period, around 1498, Leonardo and his assistants were also commissioned to paint the magnificent trompe-l’œil decoration of the Sala delle Asse in the Sforza Castle, transforming the great hall into an illusionistic pergola of interwoven mulberry trees, a true marvel of interior design.

Read more about: Decoding Da Vinci: A People Magazine Journey Through the Life and Legacy of the Renaissance’s Ultimate Genius

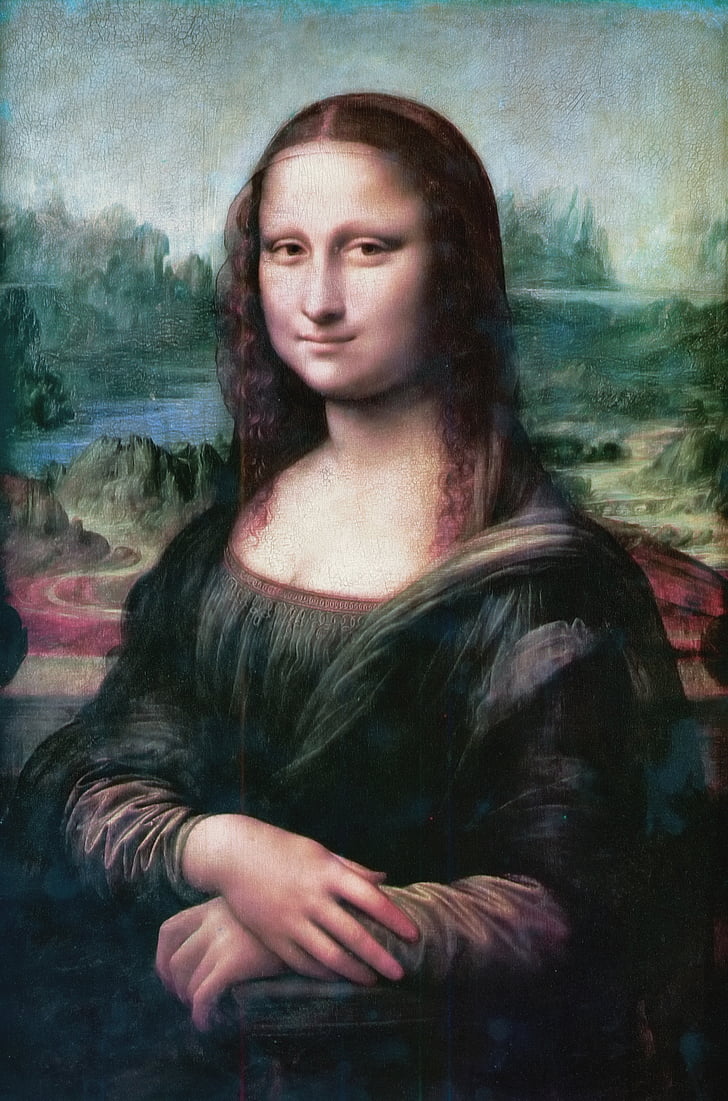

6. **The Mona Lisa: Unveiling the World’s Most Famous Smile**Among the array of masterpieces Leonardo created, few command as much global recognition and enduring fascination as the small portrait known as the ‘Mona Lisa,’ or ‘La Gioconda,’ meaning ‘the laughing one.’ Begun by October 1503, during his second Florentine period, this painting of Lisa del Giocondo has, in the present era, become arguably the most famous painting in the world. Its fame is profoundly rooted in the elusive smile on the woman’s face, a mystery that has captivated viewers for centuries.

This enigmatic quality is often attributed to the subtly shadowed corners of the mouth and eyes, which create an ambiguity that makes the exact nature of the smile impossible to definitively determine. This unique shadowy effect, for which the work is renowned, came to be known as ‘sfumato,’ or ‘Leonardo’s smoke,’ a testament to his innovative technique of blending tones and colors so subtly that they melt into one another without perceptible lines. Vasari himself marveled at it, writing that the smile was “so pleasing that it seems more divine than human, and it was considered a wondrous thing that it was as lively as the smile of the living original.”

Beyond the smile, other characteristics contribute to the painting’s timeless allure. The unadorned dress directs the viewer’s attention squarely to the eyes and hands, avoiding distraction from extraneous details. The dramatic landscape background, appearing almost in a state of flux, adds to its mysterious atmosphere, while the subdued coloring enhances its profound elegance. The extremely smooth painterly technique, employing oils laid on much like tempera and blended on the surface so that the brushstrokes are indistinguishable, was considered so masterful that Vasari expressed it would make even “the most confident master … despair and lose heart.” Adding to its remarkable status is its perfect state of preservation, with no sign of repair or overpainting, a rarity for a panel painting of its age, allowing us to experience Leonardo’s genius almost exactly as he intended.

7. **The Last Supper: A Moment Frozen in Time**Among Leonardo’s most iconic and impactful creations from his first Milanese period is “The Last Supper,” a monumental mural commissioned for the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie. This painting, executed between approximately 1492 and 1498, captures the intensely dramatic moment when Jesus announces to his disciples, “one of you will betray me,” and records the diverse expressions of consternation and disbelief that ripple through the group. It is a masterpiece not only of composition but also of characterization, revealing Leonardo’s profound understanding of human emotion and his ability to translate it onto canvas.

Contemporary accounts offer fascinating glimpses into Leonardo’s working process. The writer Matteo Bandello noted that Leonardo would sometimes paint from dawn until dusk without pause, yet at other times, he would abstain from painting for three or four days, a method that bewildered the convent’s prior. Leonardo, facing the challenge of depicting the faces of Christ and the traitor Judas, even famously suggested to Duke Ludovico Sforza that he might be compelled to use the prior as his model if hounded further, demonstrating his commitment to finding the perfect physiognomic expression for each figure.

Despite its initial acclaim as a triumph of design, “The Last Supper” sadly deteriorated rapidly due to Leonardo’s experimental technique. Instead of employing the reliable fresco method, he chose to use tempera over a ground that was primarily gesso, a medium better suited for panel painting. This innovative, yet ultimately flawed, approach resulted in a surface prone to mold and flaking. Within a century of its creation, the painting was described by one viewer as “completely ruined.” Nevertheless, its powerful narrative and masterful composition have ensured its status as one of the most reproduced religious paintings of all time, inspiring countless copies across various mediums and cementing its place in the Western canon.

8. **Visionary Engineer: Concepts Ahead of His Time**While Leonardo’s artistic achievements are widely celebrated, his genius extended profoundly into the realms of engineering and invention, revealing a mind constantly pushing the boundaries of what was technologically possible. He was revered for his technological ingenuity, conceptualizing a myriad of machines that were astonishingly ahead of his era. These included detailed designs for flying machines, an armored fighting vehicle resembling a tank, concentrated solar power devices, and even a ratio machine that could potentially function as an adding machine, alongside the innovative double hull for ships.

The sheer ambition and scope of these designs underscore his visionary outlook. However, the practical realization of many of his grandest inventions was severely constrained by the technological limitations of the Renaissance. The modern scientific approaches to metallurgy and engineering, crucial for constructing such complex mechanisms, were still in their infancy. Consequently, relatively few of his designs were ever built or even truly feasible during his lifetime, remaining largely confined to the pages of his meticulously illustrated notebooks.

Despite these larger-scale constraints, Leonardo’s inventive spirit also yielded more modest, yet impactful, contributions. Some of his smaller inventions found their way into the world of manufacturing without much fanfare. Examples include an automated bobbin winder, which would have significantly enhanced textile production, and a machine designed for testing the tensile strength of wire, highlighting his practical application of scientific principles to industrial processes. These smaller, unheralded innovations further attest to his multifaceted genius and his deep engagement with the mechanical world.

9. **A Scientific Mind: Unpublished Discoveries**Beyond his celebrated engineering concepts, Leonardo’s relentless empirical thinking led him to make substantial scientific discoveries across an impressive array of disciplines. His notebooks, a veritable treasure trove of thousands of pages, serve as an unparalleled testament to his intellectual curiosity and his systematic approach to understanding the natural world. They are filled with intricate drawings and meticulous notes on subjects as diverse as anatomy, astronomy, botany, cartography, and even the ancient records of palaeontology.

Leonardo delved deep into the intricacies of the human body, conducting dissections and producing anatomical drawings of astonishing accuracy and detail. His studies laid foundational groundwork that would not be fully appreciated for centuries. He also made significant discoveries in civil engineering, hydrodynamics, geology, optics, and tribology—the study of friction, wear, and lubrication. His observations on geological formations, the movement of water, and the properties of light were often revolutionary, demonstrating a scientific method that was remarkably modern in its empirical rigor.

A significant aspect of Leonardo’s scientific endeavors, and perhaps one of the great historical ironies, is that he did not publish his findings. Consequently, his profound discoveries and innovative theories in these various fields had little to no direct influence on the scientific development of his lifetime or the immediate generations that followed. Nevertheless, these notebooks have incited continuous interest and admiration since his death, offering future generations a profound glimpse into a mind that was, in many respects, centuries ahead of its time, revealing a systematic and scientific approach to inquiry far beyond his artistic fame.

10. **The Enigmatic Personal Life: Friends, Students, and Speculations**Despite leaving behind thousands of pages in his notebooks and manuscripts, Leonardo da Vinci scarcely made direct reference to his personal life, leaving much to speculation and interpretation by later biographers and scholars. During his lifetime, his extraordinary powers of invention, “great physical beauty,” and “infinite grace,” as described by Vasari, alongside other aspects of his life, naturally drew considerable curiosity. One such noted characteristic was his deep love for animals, evidenced by accounts, including Vasari’s, of him purchasing caged birds to set them free, possibly indicating vegetarianism.

Leonardo cultivated friendships with many notable figures of his time, enriching his intellectual and social circles. Among them was the mathematician Luca Pacioli, with whom he collaborated on the influential book “Divina proportione” in the 1490s. While his relationships with women were few and primarily platonic, such as his friendships with Cecilia Gallerani and the Este sisters, Beatrice and Isabella, it is his intimate relationships with his pupils that have particularly fascinated historians and critics. Francesco Melzi, who became his devoted companion and principal heir, described Leonardo’s feelings for his pupils as “loving and passionate.”

The nature of these relationships, particularly with his long-time pupil Salaì, and Melzi, has been the subject of considerable debate regarding Leonardo’s uality, a trend that began in the mid-16th century and was notably revived by Sigmund Freud in the 19th and 20th centuries. In 1476, at the age of twenty-four, court records show Leonardo and three other young men were charged with sodomy in an incident involving a known male prostitute; however, these charges were dismissed due to lack of evidence, with speculation that the Medici family’s influence played a role. Since then, much has been written about his presumed homosexuality and its perceived manifestations in his art, particularly in the androgyny and eroticism observed in works like “Saint John the Baptist” and “Bacchus,” and more explicitly in some of his erotic drawings, adding another layer to the enigma of this Renaissance master.

11. **Mastery of Technique: Sfumato and Beyond**Leonardo da Vinci’s fame as a painter, which for four centuries was the primary basis of his renown, rested significantly on his innovative techniques for laying on paint and his profound understanding of the natural world. The qualities that render his works unique and timeless include his detailed knowledge of anatomy, light, botany, and geology, all of which he integrated seamlessly into his artistic creations. His keen interest in physiognomy—the study of facial features and expressions—and the subtle ways humans register emotion through expression and gesture, allowed him to imbue his figures with an unprecedented sense of psychological depth and realism.

One of his most revolutionary contributions to painting technique was “sfumato,” often referred to as “Leonardo’s smoke.” This method involves the subtle gradation of tone and color, allowing them to melt into one another without perceptible lines or borders. The effect creates a soft, hazy quality, particularly evident in the “Mona Lisa’s” elusive smile, where the shadowed corners of the mouth and eyes create an ambiguity that makes the exact nature of the smile impossible to definitively determine. Vasari himself marveled at this effect, noting that the smile was “so pleasing that it seems more divine than human.”

Beyond sfumato, Leonardo’s painterly technique was characterized by an extreme smoothness. He employed oils, laying them on much like tempera and meticulously blending them on the surface until the brushstrokes became virtually indistinguishable. This meticulous approach resulted in a flawlessly rendered surface, a level of mastery that Vasari believed would make even “the most confident master… despair and lose heart.” This combination of scientific observation, psychological insight, and groundbreaking technical innovation ensured that his handful of authenticated or attributed works, though few, stand among the greatest masterpieces in the history of Western art.

Read more about: The Enduring Legacy: A Deep Dive into the Visionary World of Leonardo da Vinci’s Masterpieces and Mind

12. **Final Years and Enduring Legacy: Rome to France**Leonardo’s later years saw him continue his relentless pursuit of knowledge and art, moving between various European centers. From September 1513 to 1516, he resided in Rome, living in the Belvedere Courtyard of the Apostolic Palace, a vibrant artistic hub where Michelangelo and Raphael were also active. During this period, he continued his botanical studies in the Vatican Gardens and even dissected cadavers, making notes for a treatise on vocal cords, though a painting commission from the Pope was cancelled when he diverted his attention to developing a new kind of varnish, hinting at his continuous scientific curiosity over conventional artistic duties.

His final chapter unfolded in France, following an invitation from King Francis I, who had recaptured Milan in 1515. In 1516, Leonardo entered Francis’s service, graciously provided with the use of the manor house Clos Lucé, near the royal Château d’Amboise. Here, he enjoyed the patronage and friendship of the King, frequently visited by Francis, and continued to design ambitious projects, including plans for an immense castle town at Romorantin and even constructing a mechanical lion that, during a pageant, walked towards the King and, upon being struck by a wand, opened its chest to reveal a cluster of lilies, showcasing his enduring ingenuity and theatrical flair.

Read more about: Decoding Da Vinci: A People Magazine Journey Through the Life and Legacy of the Renaissance’s Ultimate Genius

Accompanied by his devoted friend and apprentice Francesco Melzi, and supported by a generous pension, Leonardo spent his last three years in France. Although records from this period suggest his right hand became paralytic around the age of 65, he continued to work in some capacity until becoming ill and bedridden for several months. Leonardo died at Clos Lucé on May 2, 1519, at the age of 67, possibly due to a stroke. Francis I, who had become a close friend, was reportedly with him at his deathbed. Melzi, as the principal heir, received Leonardo’s paintings, tools, library, and personal effects, ensuring the preservation of his immense legacy. Since his death, there has never been a period when Leonardo’s achievements, diverse interests, personal life, and empirical thinking have failed to incite interest and admiration, solidifying his status as a perpetual source of fascination and a figure whose influence on culture remains boundless. He truly epitomizes a genius whose impact transcends time, making him a frequent namesake and subject in culture, and forever cementing his place as a visionary whose collective works are matched only by few.