The concept of womanhood, encompassing biology, identity, and societal roles, represents a profound and multifaceted aspect of human existence. Far more than a mere biological classification, the term ‘woman’ evokes a rich tapestry of historical transformations, cultural nuances, and evolving understandings of identity and societal position. Unpacking this complex term requires a thorough examination of its etymological roots, its biological underpinnings, and the dynamic interplay of gender and culture across various civilizations and eras.

Historically, the English word ‘woman’ has undergone significant linguistic evolution. Tracing its origins back through the past millennium, one finds its progression from ‘wīfmann’ to ‘wīmmann’ to ‘wumman,’ ultimately arriving at its modern spelling. In Old English, the term ‘mann’ held a gender-neutral meaning, akin to the contemporary ‘person’ or ‘someone.’ The specific designation for ‘woman’ was ‘wīf’ or ‘wīfmann,’ literally translating to ‘woman-person.’ Conversely, ‘man’ was denoted by ‘wer’ or ‘wǣpnedmann,’ derived from ‘wǣpn,’ meaning ‘weapon’ or ‘penis.

Following the Norman Conquest, a notable linguistic shift occurred: ‘man’ gradually began to signify ‘male human,’ largely superseding ‘wer’ by the late 13th century. The consonants /f/ and /m/ in ‘wīfmann’ eventually coalesced to form the modern ‘woman,‘ while ‘wīf’ narrowed its meaning to specifically denote a married woman, becoming ‘wife.’ It is a common misconception that the term ‘woman’ is etymologically linked to ‘womb,’ a word that actually originates from the Old English ‘wamb,’ meaning ‘belly’ or ‘uterus.

Beyond its etymology, the terminology surrounding ‘woman’ also merits attention. The word can be used broadly to refer to any female human or, more specifically, to an adult female human, distinguishing her from a ‘girl.’ The term ‘girl’ itself originally referred to a ‘young person of either sex’ in English, only acquiring its specific meaning as a female child around the beginning of the 16th century. While colloquially sometimes used for young or unmarried women, feminists in the early 1970s challenged such usage due to its potential to cause offense, leading to the decline of terms like ‘office girl.’ However, in some cultures, ‘girl’ or its equivalent is still used for never-married women, similar to the now largely obsolete English terms ‘maid’ or ‘maiden.

The social sciences have significantly reshaped the understanding of what it means to be a woman since the early 20th century, particularly as women gained more rights and greater workforce representation. Scholarship in the 1970s notably shifted towards focusing on the sex–gender distinction and the social construction of gender. Different terms describe the quality of being a woman: ‘womanhood’ refers to the state of being a woman, while ‘femininity’ denotes a set of typical female qualities linked to certain gender role attitudes. ‘Womanliness’ is similar to ‘femininity’ but often associated with a different perspective on gender roles. Legally, age 18 is frequently considered the age of majority, or legal adulthood, though biologically, menarche, the onset of menstruation, typically occurs around age 12–13, marking the capacity for pregnancy.

From a biological standpoint, distinctions between female and male bodies are fundamental. Female humans typically possess two X chromosomes in their cells, while male humans have an X and a Y chromosome. Early fetal development sees all embryos start with phenotypically female genitalia until weeks 6 or 7, when the SRY gene on the Y chromosome triggers gonad differentiation into testes in male embryos. Female sex differentiation, in contrast, proceeds independently of gonadal hormones.

Hormonal characteristics are central to female biology. Female puberty is marked by bodily changes enabling sexual reproduction, driven by hormones secreted by the ovaries in response to pituitary gland signals. These hormones stimulate maturation, including increased height and weight, body hair growth, breast development, and menarche. Most girls experience menarche between the ages of 12–13, becoming capable of pregnancy and childbirth. Pregnancy typically involves internal fertilization, though in vitro fertilization offers an external option.

Humans generally bear a single offspring per pregnancy but are considered altricial, meaning newborns are undeveloped and require extensive parental care. Women usually reach menopause, the permanent cessation of menstrual periods and reproductive ability, between the ages of 49–52. Uniquely among most large mammals, human lifespan often extends many years beyond menopause, a phenomenon some biologists attribute to kin selection, wherein grandmothers contribute to the care of grandchildren and other family members.

The female reproductive system comprises internal genitalia such as the ovaries, which produce ova; fallopian tubes, which transport egg cells; the uterus, which protects and nurtures the developing fetus; and the vagina, used in copulation and birth. The external female genitalia, collectively known as the vulva, include the clitoris, labia majora, labia minora, and vestibule. Mammary glands, hypothesized to have evolved from apocrine-like glands, produce milk, a defining characteristic of mammals. In mature women, breast prominence often exceeds that in other mammals, thought to be partly a result of sexual selection.

Estrogens, the primary female sex hormones, significantly shape the female body, promoting the development of secondary sexual characteristics like breasts and widened hips during puberty. Testosterone, conversely, inhibits breast development and promotes muscle and facial hair. The circulatory system also presents sex differences: women have lower hematocrit (36% to 48%) and hemoglobin levels (12.0 to 15.5 g/dL) than men, due to lower testosterone. Women’s hearts also exhibit finer-grained muscle textures and age more slowly than men’s hearts.

Globally, girls are born slightly less frequently than boys, with a ratio of approximately 1:1.05. In 2015, there were 1018 men for every 1000 women worldwide. It is also important to acknowledge intersex women, who are born with sex characteristics that do not fit typical notions of female biology, often with ambiguous genitalia. While many are assigned female at birth, medical practices in this area remain a subject of controversy, and some intersex conditions are associated with diverse gender identities.

Sexuality and gender are integral to the experience of womanhood. Most women identify as heterosexual, attracted to men, and are cisgender, meaning their female sex assigned at birth aligns with their female gender identity. Femininity, also called womanliness or girlishness, describes a set of attributes, behaviors, and roles typically associated with women and girls. While socially constructed, certain behaviors deemed feminine can also have biological influences, the extent of which remains a subject of debate. It is distinct from biological sex, as both men and women can exhibit feminine traits.

Transgender women, assigned male at birth, may experience gender dysphoria, the distress arising from a discrepancy between gender identity and assigned sex. Gender-affirming care, including social or medical transition, can address this. Social transition may involve changes in name, hairstyle, clothing, and pronouns, while medical transition can include feminizing hormone therapy and gender-affirming surgeries, leading to the development of female secondary sex characteristics and typical female anatomy.

Health considerations for women extend beyond reproduction to encompass subtle sex differences across biological scales, from molecular to behavioral. These differences are influenced by sex chromosomes, hormones, lifestyle, metabolism, immune system function, and environmental sensitivities. Specific diseases like lupus, breast cancer, cervical cancer, or ovarian cancer primarily affect women. Gynecology is the medical field dedicated to female reproduction and reproductive organs.

Maternal mortality remains a grave concern, defined by the WHO as the death of a woman during pregnancy or within 42 days of termination, from causes related to or aggravated by the pregnancy. In 2008, over 500,000 women died annually from pregnancy and childbirth complications, prompting the WHO to advocate for midwife training. In 2017, 94% of maternal deaths occurred in low and lower-middle-income countries, predominantly in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, largely due to pre-eclampsia, unsafe abortion, and severe bleeding or infections. While some regions, like most European countries, Australia, Japan, and Singapore, are very safe for childbirth, the global disparity is stark.

Life expectancy generally favors women worldwide, who live six to eight years longer than men. This advantage begins at birth, with newborn girls having a higher survival rate in their first year. However, this varies by region; discrimination against women has, in some parts of Asia, led to men living longer. The difference is attributed to both biological advantages and gendered behavioral differences, with women less likely to engage in risky behaviors like smoking and reckless driving. Yet, in some developed countries, this gap is narrowing due to women adopting unhealthier behaviors and men’s health improving, though the WHO notes that women’s extra years are not always lived in good health.

Reproductive rights are fundamental human rights encompassing control over sexual and reproductive health, free from coercion, discrimination, and violence. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics emphasizes mutual respect, consent, and shared responsibility in sexual and reproductive matters. The WHO reported 56 million induced abortions globally each year between 2010 and 2014, with about 25 million deemed unsafe. Unsafe abortions cause significant mortality, particularly in developing regions and sub-Saharan Africa, often due to restrictive laws, poor service availability, high costs, stigma, and unnecessary procedural hurdles.

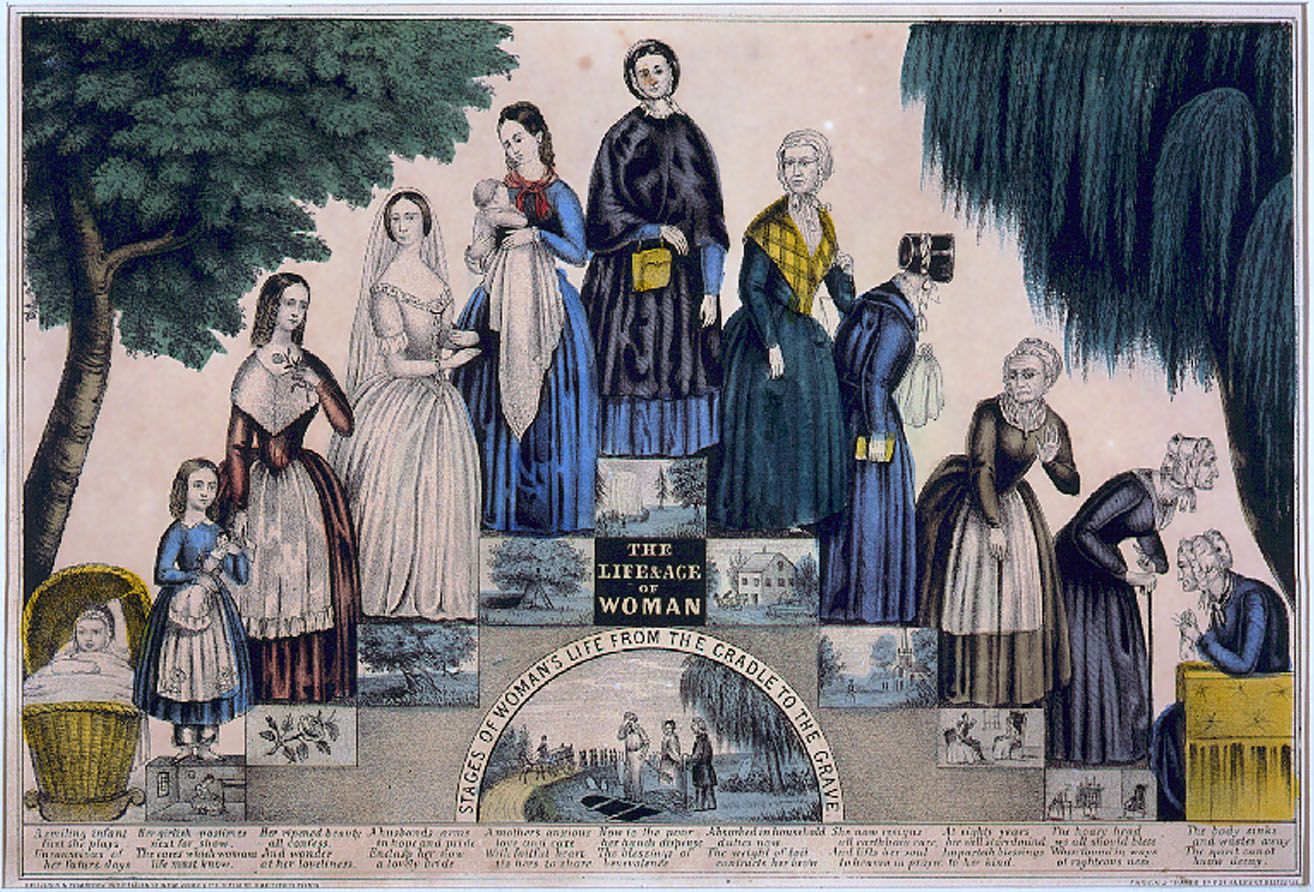

Throughout history, traditional gender roles, especially within patriarchal societies, have often defined and limited women’s activities and opportunities, contributing to gender inequality. Many religious doctrines and legal systems have historically stipulated specific rules for women. However, the 20th century saw restrictions loosen in many societies, granting women broader access to careers and higher education.

Notable women from antiquity illustrate early contributions and leadership. Neithhotep, circa 3200 BCE, was the wife of Narmer and possibly the first queen of ancient Egypt. Merneith, around 3000 BCE, served as consort and regent, potentially ruling Egypt independently. Peseshet, circa 2600 BCE, was a physician in Ancient Egypt. Kugbau, circa 2500 BCE, a taverness, was chosen to rule Sumer and later deified as “Kubaba.” Enheduanna, around 2285 BCE, was the high priestess of the Moon God in Ur and is possibly the first known poet and named author of either gender. Shibtu, circa 1775 BCE, queen of Mari, ruled as regent during her husband’s absence, wielding extensive administrative powers.

The symbol for the planet and Roman goddess Venus (♀), or Aphrodite in Greek, is universally used to represent the female sex. In ancient alchemy, this Venus symbol also stood for copper and was associated with femininity. These historical figures and symbols highlight a legacy of female presence and influence, even within often restrictive societal frameworks.

In recent history, gender roles have significantly transformed. Earlier, children’s occupational aspirations often differed by gender from a young age. Traditionally, middle-class women focused on domestic tasks and childcare, while economic necessity compelled poorer women to seek employment outside the home, often in lower-paying jobs than those available to men. Shifts in the labor market, from demanding factory jobs to cleaner office work requiring more education, facilitated a change in attitudes towards women at work. This contributed to a revolution, leading women to become more career and education-oriented.

Despite institutional efforts in the 1980s to equalize workplace conditions, professional women frequently bore primary responsibility for domestic labor and childcare, limiting their career advancement. Historically, U.S. women’s colleges even required female faculty to remain single, believing a woman could not manage two full-time professions simultaneously. As sociologist Harriet Zuckerman observed, “Being a scientist and a wife and a mother is a burden in a society that expects women more often than men to put family ahead of career” (p. 93).

Movements advocating for equal opportunities and rights irrespective of gender have been instrumental. Economic changes combined with feminist efforts have, in recent decades, expanded women’s access to careers beyond traditional homemaking in many societies. Yet, modern women in Western society continue to face challenges in the workplace, education, healthcare, politics, and motherhood. Sexism, though varying in form and gravity, remains a barrier for women globally.

Educational disparities persist, reflected in the Gender Parity Index in school enrollment across countries. Girls typically exhibit higher reading skills, while gender pay gaps vary by country and age group. Despite women accounting for over half of university graduates in several OECD countries, they only receive 30% of tertiary degrees in science and engineering fields and comprise only 25% to 35% of researchers in most OECD nations. Research indicates that while women attend prestigious universities at similar rates to men, they face greater difficulty securing faculty positions, especially at top-tier institutions.

Religious doctrines frequently stipulate specific gender roles, spiritual authority for women, social interactions, and dress codes, which can influence criminal and family law in many countries. The relationship between religion, law, and gender equality is a subject of ongoing international discussion.

Violence against women is a widespread problem, defined by the UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women as “any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.” This violence manifests within families, communities, and can be perpetrated or condoned by the state. The declaration explicitly states that “violence against women is a manifestation of historically unequal power relations between men and women.

Social norms in many parts of the world hinder progress in protecting women from violence. UNICEF surveys reveal high percentages of women in some countries who believe a husband is justified in hitting his wife under certain circumstances, reaching as high as 90% in Afghanistan and Jordan. A 2010 Pew Research Center survey found significant support for stoning as punishment for adultery in countries like Egypt and Pakistan. Specific forms of violence include female genital mutilation, sex trafficking, forced prostitution, forced marriage, rape, sexual harassment, honor killings, acid throwing, and dowry-related violence. Laws addressing these issues vary, with some forms like marital rape only recently recognized as criminal offenses in many jurisdictions.

Historically, violence against women has included the burning of witches, the sacrifice of widows (such as sati), and foot binding. Witch trials were common in Europe and its colonies from the 15th to 18th centuries, and today, accusations of witchcraft still lead to serious violence against women in parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, rural North India, and Papua New Guinea. Saudi Arabia, for instance, still punishes witchcraft with death. During times of war and armed conflict, sexual violence against women, often in the form of war rape and sexual slavery, greatly increases, as tragically evidenced in conflicts from the Armenian Genocide to the recent sexual jihad by ISIL.

Clothing, fashion, and dress codes for women vary significantly across cultures, influenced by local traditions, religious tenets, social norms, and fashion trends. Ideas about modesty differ widely, and laws in many jurisdictions regulate women’s attire. This is particularly evident with Islamic dress, where some countries mandate headscarves while others forbid or restrict face coverings in public, leading to highly controversial legal and social debates.

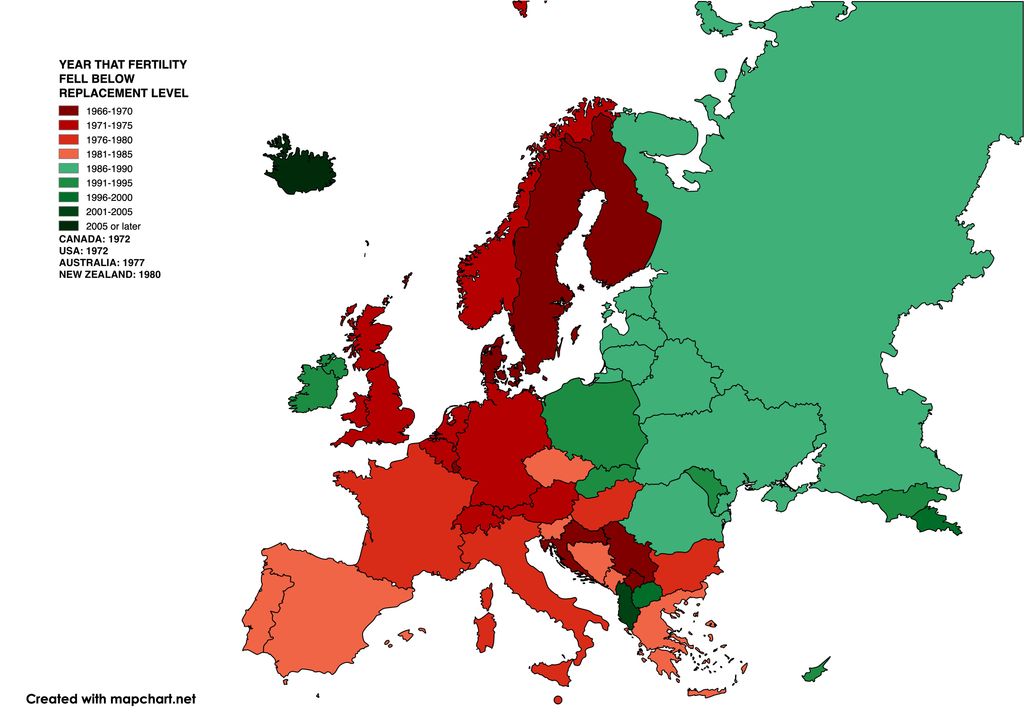

Fertility and family life reveal significant global variations. The total fertility rate (TFR), the average number of children born to a woman, ranged from a high of 6.62 in Niger to a low of 0.82 in Singapore in 2016. While high TFRs in Sub-Saharan Africa contribute to overpopulation issues, many Western countries face sub-replacement fertility rates, leading to population aging and decline. Family structures have also shifted, particularly in the West, moving from extended to nuclear family arrangements and towards non-marital fertility. While births outside marriage are accepted in some regions, they are highly stigmatized in others, potentially leading to ostracism or even honor killings. Furthermore, sex outside marriage remains illegal in many countries.

The social role of the mother also varies. In some parts of the world, women with dependent children are expected to be stay-at-home mothers, dedicating all energy to child-rearing, while in others, mothers commonly return to paid work. Education access for women, while improving globally, is not yet universal. In some Western countries like the United States, women have surpassed men in earning associate, bachelor’s, and master’s degrees, and nearly match men in doctorates.

However, in 2020, 87% of the world’s women were literate, compared to 90% of men, but only 59% in sub-Saharan Africa. While the educational gender gap has narrowed in OECD countries, women remain underrepresented in science and engineering tertiary degrees and research positions. Despite studying at prestigious universities at the same rate as men, women often face hurdles in securing faculty positions in higher education.

The journey through the multifaceted landscape of womanhood reveals a narrative of profound biological intricacies, enduring historical roles, and dynamic societal transformations. From the subtle dance of hormones shaping physiological development to the complex interplay of cultural expectations and personal agency, women have continually navigated and reshaped their existence. The challenges of gender inequality, violence, and health disparities persist, yet the undeniable strides in education, professional opportunity, and the ongoing pursuit of reproductive rights stand as powerful testaments to resilience and progress. Understanding womanhood means acknowledging this rich, evolving tapestry, recognizing both the universal threads that connect women across time and place, and the diverse patterns that define individual lives and experiences. It is a continuous story of growth, struggle, and the unwavering quest for equality and full human flourishing.